Live Forever: The return of the Fafactory

I

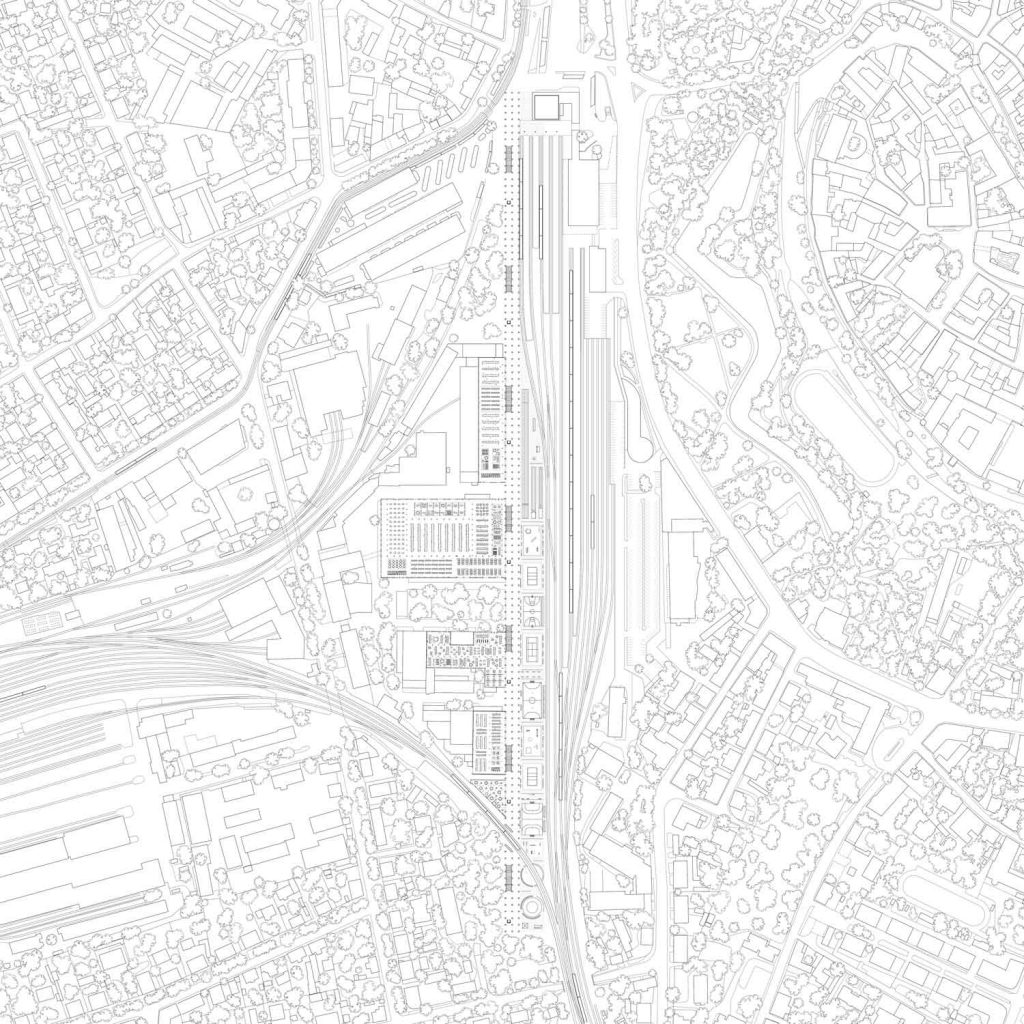

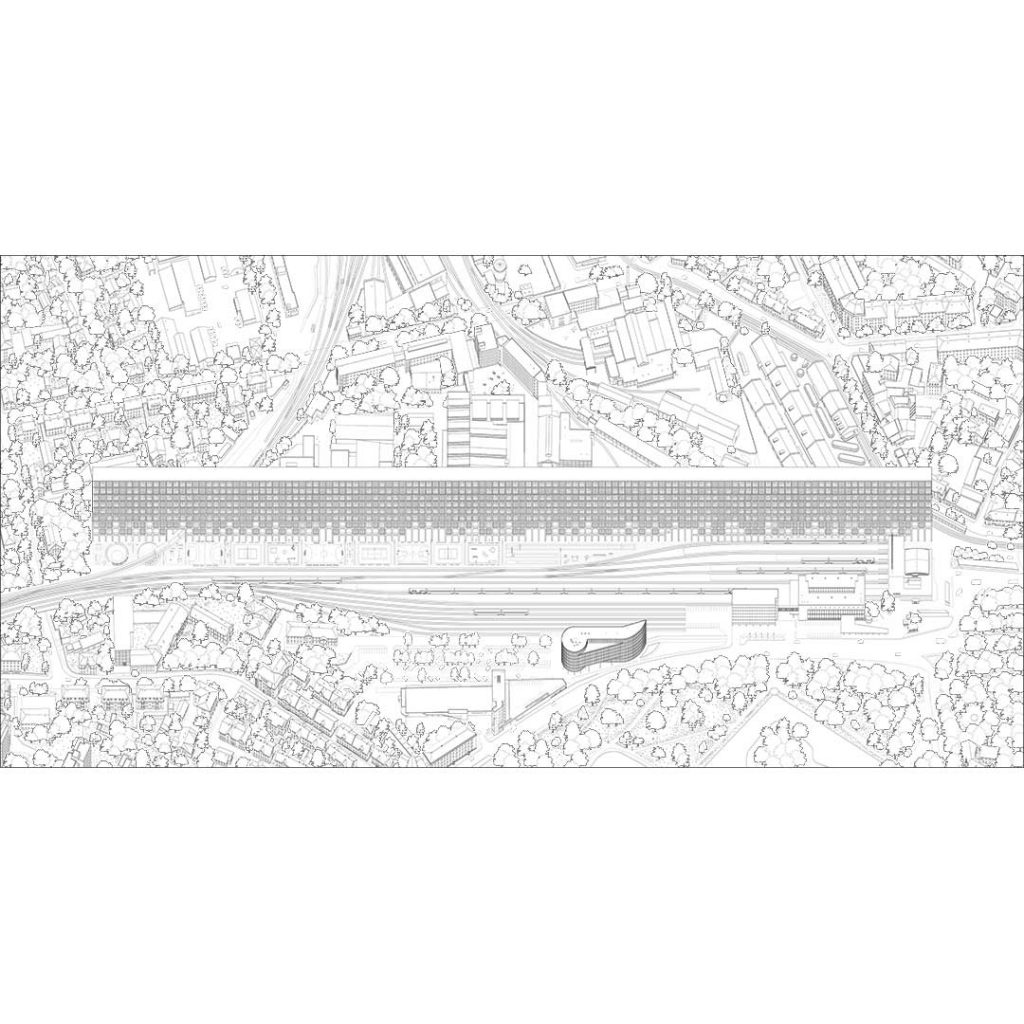

We propose a building for 1,600 inhabitants located within the Telliskivi Creative Campus, a triangular site, adjacent to Balti Central Station and completely surrounded by railway lines. The site is already occupied by a former electronics production plant which has been recently transformed into a cultural hub. Our proposal acknowledges the existing state of the area and complements it with living and working facilities. The proposed building appropriates the main pavilion of Balti Station as the main access to the area.

Proponemos un edificio para 1.600 habitantes ubicado dentro del Campus Creativo de Telliskivi, un lugar triangular, adyacente a la Estación Central de Balti y completamente rodeado de líneas ferroviarias. El sitio ya está ocupado por una antigua planta de producción de productos electrónicos que se ha transformado recientemente en un centro cultural. Nuestra propuesta reconoce el estado actual de la zona y la complementa con instalaciones para vivir y trabajar. El edificio propuesto se apropia del pabellón principal de la estación Balti como el acceso principal al área.

II

Asked what they want to become in the future, circa 60 percent of the young people living in the city of Berlin answered that they want to become artists. This is an astonishing statistical fact, that tells us more about our ethos than any sociological and economic inquiry. If once being an artist was being a social outsider, today it has become a widespread form of life. Being an artist today does not mean being a painter, a sculptor or even an experimental or conceptual artist. To be an artist means to be a producer in the wider sense of the term. To be an artist is more about assuming a way of living that is flexible and does not obey to predetermined job descriptions. This condition may be read as the apotheosis of what Richard Florida celebrated ten years ago as the ‘flight of the creative class’, but in fact, in the past years it has shown its dark side. Apart from being the now infamous ‘pioneers’ in the gentrification of once poor and thus affordable neighborhoods, artists and creative workers are the most vulnerable segment of contemporary society. In spite of their increasingly overloaded schedule, creative workers live in increasingly precarious conditions with no secure income, no social security, and with the threat of not having a proper space (or no space at all) to live and work. The paradox of this situation is that creativity is one of the most important forms of production within ‘advanced economies’. At the same time, creative workers have much less social security and welfare than factory workers. Moreover, they lack a visible and tangible representation that goes beyond the squatted industrial building and the fancy coffee shop.

Cuando se les preguntó en qué quieren convertirse en el futuro, alrededor del 60 por ciento de los jóvenes que viven en la ciudad de Berlín respondió que quieren ser artistas. Este es un hecho estadístico asombroso, que nos dice más sobre nuestro ethos que cualquier investigación sociológica o económica. Si alguna vez ser artista era una rareza social, hoy se ha convertido en una forma de vida generalizada. Ser artista hoy no significa ser pintor, escultor o incluso artista experimental o conceptual. Ser artista significa ser productor en el sentido más amplio del término. Ser artista trata más de asumir una forma de vida flexible y que no obedece a descripciones de trabajo predeterminadas. Esta condición puede leerse como la apoteosis de lo que Richard Florida celebró hace diez años como el “vuelo de la clase creativa”, pero de hecho, en los últimos años ha mostrado su lado más amargo. Además de haberse convertido en infames “pioneros” de la gentrificación de vecindarios que alguna vez fueron pobres y, por lo tanto, asequibles, los artistas y trabajadores creativos son el segmento más vulnerable de la sociedad contemporánea. A pesar de su horario cada vez más sobrecargado, los trabajadores creativos viven en condiciones cada vez más precarias, sin ingresos seguros, sin seguridad social y con la amenaza de no tener un espacio adecuado (o ningún espacio) para vivir y trabajar. La paradoja de esta situación es que la creatividad es una de las formas de producción más importantes dentro de las “economías avanzadas”. Al mismo tiempo, los trabajadores creativos tienen mucha menos seguridad social y bienestar que los trabajadores de las fábricas. Por último, carecen de una representación visible y tangible que vaya más allá del edificio industrial okupado o la elegante cafetería.

III

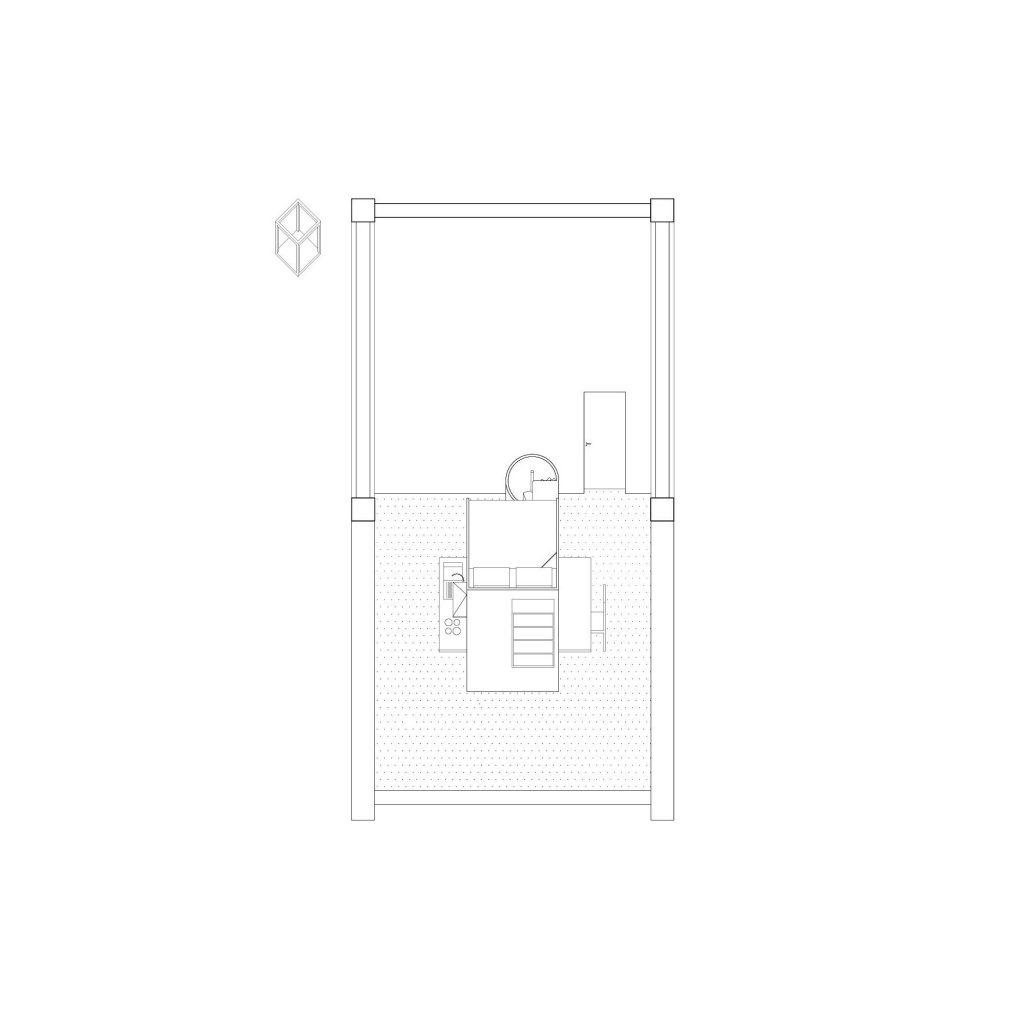

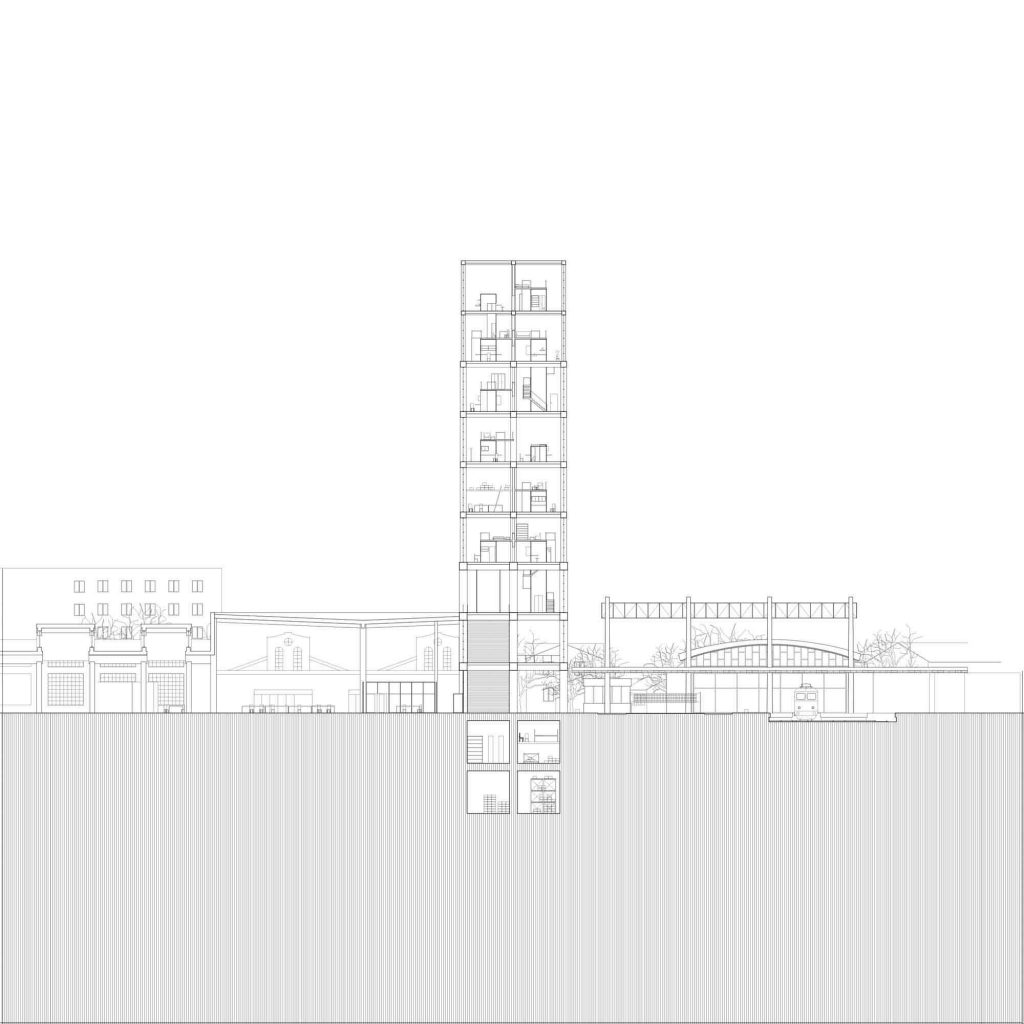

Within the theme of ‘Recycling Socialism’ our project attempts to reclaim the social dimension of architecture, not as a vintage socialist utopia, but in the realist form of a new welfare project for workers of the socalled ‘creative industry’. Our proposal consists in a single building that contains both living and working facilities for circa 1,600 inhabitants. The building is explicitly designed as a ‘Unité d’Habitation’, but unlike its illustrious predecessor, it is not made up of apartments and collective spaces, but rather of an open and flexible structure where living and working, the collective and the individual can be negotiated and adapted in different conditions of use. The basic unit of the Unité is a room that measures 6 by 6 m and that can be used both as living and working space. As a domestic space the room is for one or two persons, however, the generous height allows the instalment of one more floor. This means that the one room unit can easily become a small apartment for 3 or 4 people. The entire building is organized with the 6 x 6 m module of the room. This means that more rooms can be aggregated both horizontally and vertically.

Dentro del tema de “Reciclando el socialismo”, nuestro proyecto intenta recuperar la dimensión social de la arquitectura, no como una utopía socialista clásica, sino en la forma realista de un nuevo proyecto de bienestar para los trabajadores de la llamada “industria creativa”. Nuestra propuesta consiste en un solo edificio que contiene instalaciones tanto para vivir como para trabajar para unos 1.600 habitantes. El edificio está diseñado explícitamente como una ‘Unité d’Habitation’, pero a diferencia de su ilustre predecesor, no se compone de apartamentos y espacios colectivos, sino más bien de una estructura abierta y flexible donde vivir y trabajar, lo colectivo y el individuo puede ser negociado y adaptado en diferentes condiciones de uso. La unidad básica de la Unité es una habitación de 6 x 6 my que se puede utilizar tanto como espacio de vida como de trabajo. Como espacio doméstico la habitación es para una o dos personas, sin embargo, la generosa altura permite la instalación de un piso más. Esto significa que la unidad de una habitación puede convertirse fácilmente en un pequeño apartamento para 3 o 4 personas. Todo el edificio se organiza con el módulo de 6 x 6 m de la sala. Esto significa que se pueden agregar más habitaciones tanto horizontal como verticalmente.

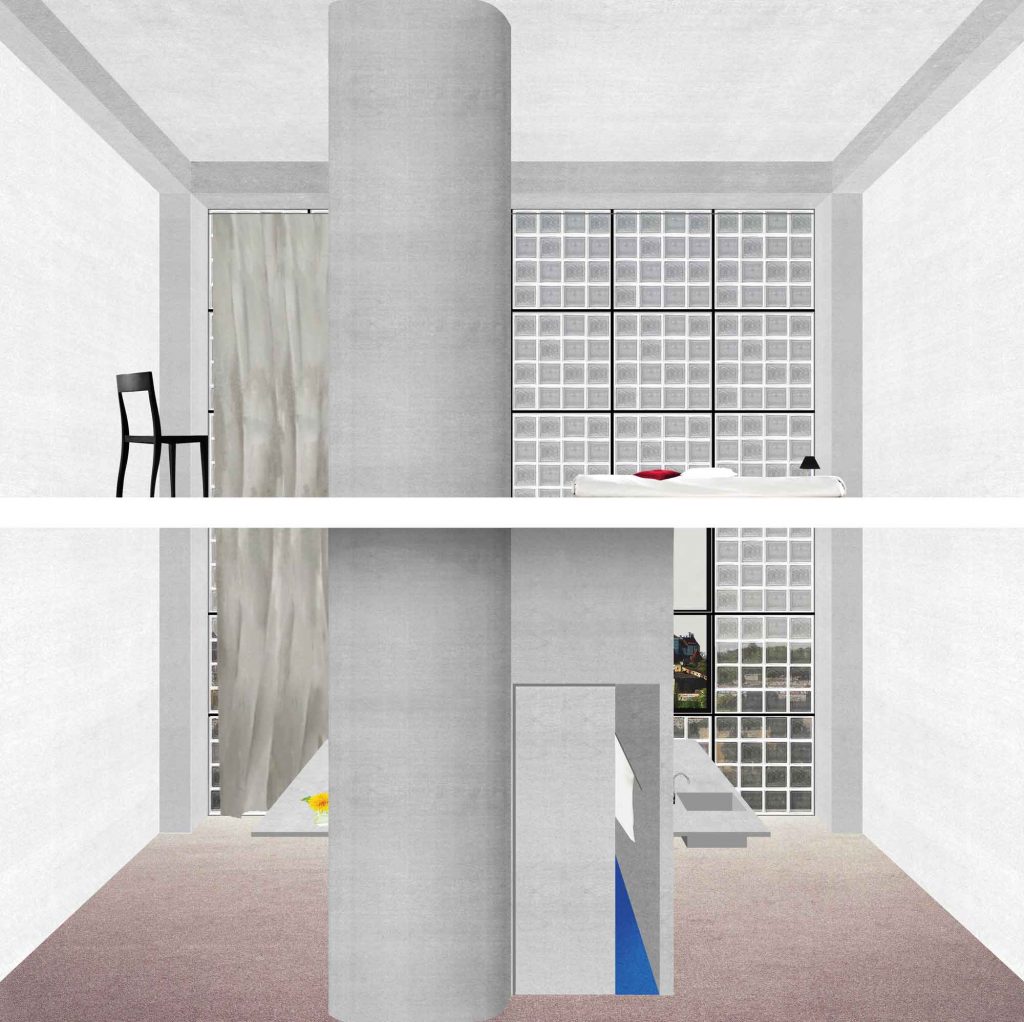

Each room can be equipped with a core that contains the basic infrastructure for living: bathroom, kitchen, bed, desk. The core is a podium on top of which there is the bed for one or two persons. The podium works both as the room core but also as an infrastructure that defines different domestic spaces without compromising the wholeness of the room.

Cada habitación puede estar equipada con un núcleo que contiene la infraestructura básica para vivir: baño, cocina, cama, escritorio. El núcleo es un podio encima del cual se encuentra la cama para una o dos personas. El podio funciona como el núcleo de la sala, pero también como una infraestructura que define diferentes espacios domésticos sin comprometer la totalidad de la sala.

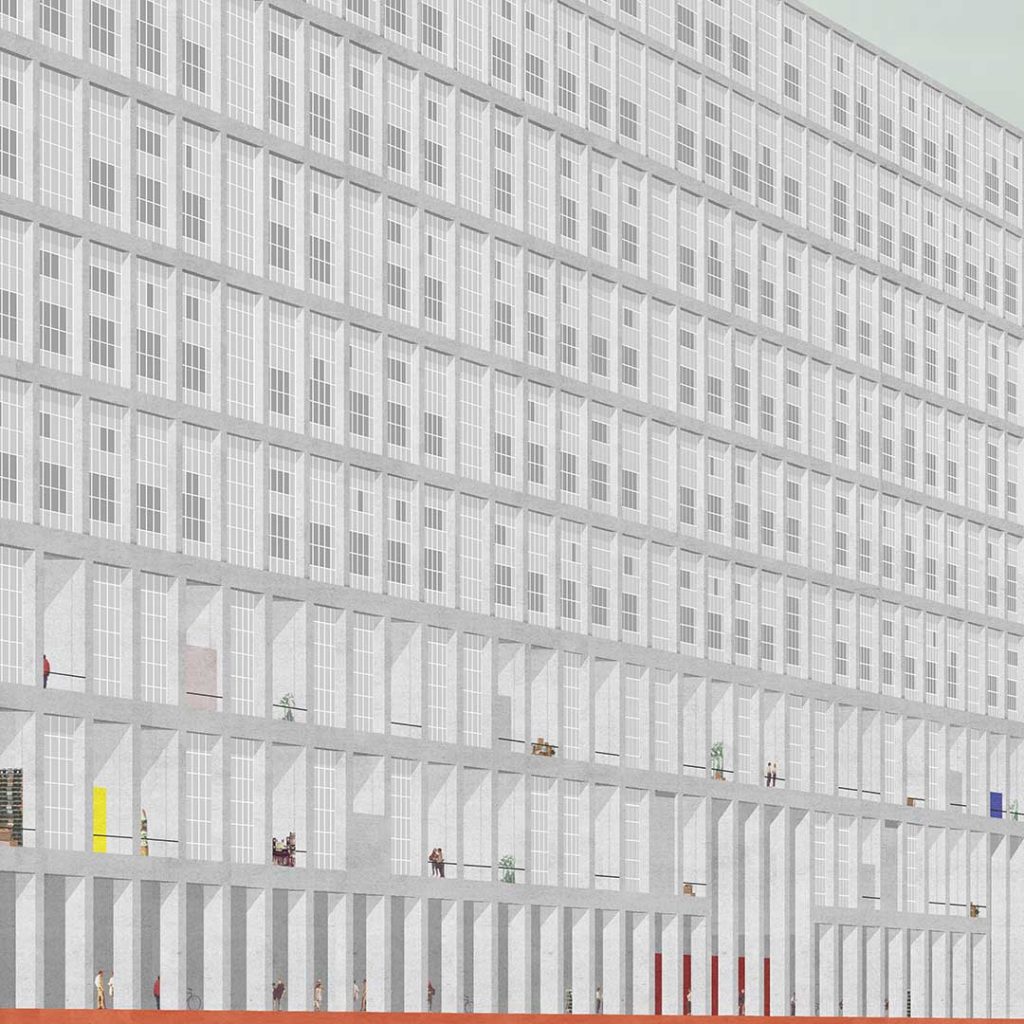

As a domestic space, the room can be both a living and working place. Individual rooms share collective spaces that are also the access to the rooms. The collective spaces work as collective living rooms shared by a maximum of 3 rooms, and which can also function as ateliers and studios. Just like in the case of the domestic space, the room can be easily divided in order to obtain more space. The sameness of the spaces and the flexibility of the structure aim to make living and working places interchangeable. At the same time, the idea of reducing the domestic space to one room makes co-sharing of facilities easier and offers the inhabitants more privacy and seclusion than in the traditional small and medium-size apartment. The simple plan of the Unité reappropriates the simplicity of the typical industrial plan where structure is minimized in order to allow maximum flexibility. At the same time, great emphasis is given to the proportions of the room, with its perfect square section made visible both inside and outside the building. The visibility of thestructure and its relentless modularity is meant to establish a common rhythm within the spaces. This structure aims to become a visible notation, a legible score: the shareable support for a potential ‘general intellect’ that informs or even orchestrates the multifarious activity of today’s economy without imposing on it a too-rigid structure. This open structure is opposed to the architecture of the apartment where the interior space is unnecessarily fragmented into small rooms and corridors. By reducing the domestic space to one (divisible) room, the interior space is not only spared from redundant square meters, but it also looks much bigger and generous than a big apartment made up of many small rooms. Above all, the project aims to acknowledge not only the indistinguishable temporal and spatial boundary between domestic life and production, but also the fact that domestic life itself is a form of production. It is for this reason that our project postulates the return of the factory as the practical but also symbolic space where the social and productive dimensions of life become spatially and physically tangible.

Como espacio doméstico, la habitación puede ser tanto un lugar para vivir como para trabajar. Las habitaciones individuales comparten espacios colectivos que también sirven para acceder a las habitaciones. Los espacios colectivos funcionan como salas de estar colectivas compartidas por un máximo de 3 habitaciones, y que pueden funcionar como ateliers o estudios. Al igual que en el caso del espacio doméstico, la habitación se puede dividir fácilmente para obtener más espacio. La uniformidad de los espacios y la flexibilidad de la estructura tienen como objetivo hacer que los lugares de vida y de trabajo sean intercambiables. Al mismo tiempo, la idea de reducir el espacio doméstico a una sola habitación facilita el uso compartido de las instalaciones y ofrece a los habitantes más privacidad y aislamiento que en el apartamento tradicional de tamaño pequeño o mediano. El plano simple de la Unité se reapropia de la sencillez del típico plano industrial donde la estructura se minimiza para permitir la máxima flexibilidad. Al mismo tiempo, se da un gran énfasis a las proporciones de la habitación, con su perfecta sección cuadrada visible tanto dentro como fuera del edificio. La visibilidad de la estructura y su implacable modularidad está destinada a establecer un ritmo común dentro de los espacios. Esta estructura pretende convertirse en una notación visible, una partitura legible: el soporte compartible de un potencial “intelecto general” que informa o incluso orquesta la actividad múltiple de la economía actual sin imponerle una estructura demasiado rígida. Esta estructura abierta se opone a la arquitectura del apartamento donde el espacio interior se fragmenta innecesariamente en pequeñas habitaciones y pasillos. Al reducir el espacio doméstico a una habitación (divisible), el espacio interior no solo se salva de los metros cuadrados redundantes, sino que también se ve mucho más grande y generoso que un gran apartamento compuesto por muchas habitaciones pequeñas. Sobre todo, el proyecto tiene como objetivo reconocer no solo la frontera temporal y espacial indistinguible entre la vida doméstica y la producción, sino también el hecho de que la vida doméstica en sí misma es una forma de producción. Es por ello que nuestro proyecto postula el regreso de la fábrica como el espacio práctico pero también simbólico donde las dimensiones social y productiva de la vida se vuelven espacial y físicamente tangibles.

IV

We imagine this building would be given for free to inhabitants who in turn can ‘pay back’ the city by offering their skills in the form of informal teaching, the organization of workshops and cultural events that can unfold in an open -ended social laboratory, open to all. For this reason, the location of the Unité d’Habitation is crucial. Its imposing, almost monumental presence is meant to make visible the social body that this architecture hosts, and at the same time it attempts to stop processes of gentrification. As the history of this phenomenon has already proven, there is a subtle link between gentrification and the aesthetic of urban form. Gentrification flourishes when an existing neighbourhood is gradually transformed by the smooth tactics of urban renewals which consist in the proliferation of small-scale spaces such as cafés, galleries and cultural institutions dispersed within the fabric of the city. These small presences act as Trojan horses of gentrification in spite of their good intentions. Their implicit tactics consist in changing the atmosphere of the district without making visible the social frictions that this transformation inevitably implies. With its monumental form, the Unité acts within and against the smooth politics of gentrification, while giving a precise and legible body to the mass of creative workers.

Imaginemos que este edificio se entregra de forma gratuita a los habitantes que a su vez pueden ‘devolver’ a la ciudad ofreciendo sus habilidades en forma de enseñanza informal: la organización de talleres y eventos culturales que pueden desarrollarse en un laboratorio social abierto a todos. Por este motivo, la ubicación de la Unité d’Habitation es crucial. Su presencia imponente, casi monumental, pretende visibilizar el cuerpo social que alberga esta arquitectura y, al mismo tiempo, intenta frenar los procesos de gentrificación. Como ya ha demostrado la historia de este fenómeno, existe un vínculo sutil entre gentrificación y estética de la forma urbana. La gentrificación florece cuando un barrio existente se transforma gradualmente mediante las suaves tácticas de renovaciones urbanas que consisten en la proliferación de espacios de pequeña escala como cafés, galerías e instituciones culturales dispersas dentro del tejido de la ciudad. Estas pequeñas presencias actúan como caballos de Troya de la gentrificación a pesar de sus buenas intenciones. Su táctica implícita consiste en cambiar el ambiente del barrio sin visibilizar los roces sociales que inevitablemente implica esta transformación. Con su forma monumental, la Unité actúa dentro y en contra de la suave política de gentrificación, al tiempo que da un cuerpo preciso y legible a la masa de trabajadores creativos.

Text by Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara.