This article is part of Infrastructural Urbanism, a series curated by Hidden Architecture where we explore the evolutionary potential over time of certain urban and architectural structures. The infrastructural nature of these projects allows them to accommodate and assume the uncertainty of future development as a project tool.

Este articulo es parte de Urbanismo Infraestructural, serie que explora el potencial evolutivo a lo largo del tiempo de determinadas estructuras urbanas y arquitectónicas. El carácter de infraestructura de estos proyectos les permite albergar y asumir la incertidumbre de un desarrollo futuro como herramienta de proyecto.

***

Context

The Mayan town of Uxmal is located in the north of the Mexican Yucatan Peninsula, about 100 kilometres south of the city of Merida. The area of influence of this Mesoamerican civilisation extended over the current territories of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and southern Mexico, specifically in the states of Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Campeche and Yucatan. The proximity to the Caribbean Sea, the tropical and humid climate and the enormous expanse of jungle that would cover an essentially flat territory, rich however in mineral resources such as sandstone, are elements that would have decisively defined the success of Mayan development, facilitating the creation of multiple cities interconnected by a dense and efficient network of roads. To the north of the Yucatan, however, the dense jungle gradually gave way to more arid, fertile slopes, large tracts of land where surface water was scarce while underground watercourses and reservoirs were filling up. In the Puuc region, the cradle of Uxmal, gentle hills enrich a monotonous landscape with their green hillocks, which disappears towards the sea.

La población maya de Uxmal se encuentra ubicada en el norte de la península mexicana del Yucatán, unos cien kilómetros al sur de la ciudad de Mérida. El área de influencia de esta civilización mesoamericana se extendió por los actuales territorios de Honduras, Guatemala, Belice y el sur de México, concretamente en los estados de Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Campeche y Yucatán. La proximidad al mar Caribe, el clima tropical y húmedo y la enorme extensión de superficie selvática que cubriría un territorio en esencia plano, rico sin embargo en recursos minerales como la roca arenisca, son elementos que habrían definido de manera determinante el éxito del desarrollo de los mayas, facilitando la creación de múltiples ciudades interconectadas entre sí por una densa y eficiente red de caminos. Al norte del Yucatán, sin embargo, la tupida selva deja paso progresivamente a fértiles laderas más áridas, grandes extensiones de territorio donde el agua en superficie escasea mientras colma cursos y yacimientos subterráneos. En la región del Puuc, cuna de Uxmal, suaves colinas enriquecen con sus verdes lomas un paisaje monótono que se pierde hacia el mar.

Interpretations of the archaeological remains found indicate that this settlement may predate the 5th century AD, although Uxmal reached its height of splendour in the Classic Period of Maya civilisation between the 6th and 10th centuries. Subsequently, the Maya suffered a major decline, abandoning the cities and returning to a more primitive way of life, abandoning all the advances they had developed in different disciplines such as mathematics, astronomy and agriculture. The causes of this decline are unclear and the hypotheses are multiple and of very different natures. Those with the greatest consensus state that the demographic pressure in the cities was a determining factor. The migration of people attracted by their prosperity may have provoked an environmental crisis due to the overexploitation of the territory, the main consequences of which would have been food shortages and the proliferation of diseases transmitted by insects and parasites. The enormous inequality between the working classes, who bore the brunt of society’s productive burden, and the wealthy ruling classes led to the outbreak of numerous social uprisings.

Interpretaciones de los restos arqueológicos hallados indican que este asentamiento podría ser anterior al siglo V de nuestra era, aunque Uxmal alcanzaría su época de esplendor en el Periodo Clásico de la civilización maya, comprendido entre los siglos VI y X. Posteriormente, los mayas sufrieron una decadencia de gran magnitud, a raíz de la cual abandonaron las ciudades para regresar a un modo de vida más primitivo, dejando de lado todos los avances que habían desarrollado en distintas disciplinas como las matemáticas, astronomía o agricultura. Las causas de este declive no son claras y las hipótesis múltiples y de muy distinta naturaleza. Aquellas que cuentan con un mayor consenso afirman que la presión demográfica existente en las ciudades fue determinante. La migración de personas atraídas por su prosperidad pudo haber provocado una crisis ambiental por la sobreexplotación del territorio, cuyas consecuencias principales habrían sido la escasez de alimento y la proliferación de enfermedades transmitidas por insectos y parásitos. La enorme desigualdad entre las clases populares, sobre las que recaía todo el peso productivo de la sociedad, y unas clases dirigentes muy abundantes originó el estallido de múltiples revueltas sociales.

Although invasions by Aztec and Toltec tribes from northern Mexico revitalised some cities, the last inscriptions found at Uxmal date from 909. When the conquistadors from Castile arrived in the Yucatan in the early 16th century, they found that most of the urban structures had been abandoned for centuries.

Aunque las invasiones de tribus aztecas y toltecas procedentes del norte de México revitalizaron algunas ciudades, las últimas inscripciones halladas en Uxmal datan del año 909. Cuando los conquistadores procedentes de Castilla llegaron a Yucatán a inicios del siglo XVI, encontraron que la mayor parte de las estructuras urbanas permanecían abandonadas desde hacía siglos.

References

Almost all the cities of the Maya civilisation have an urban structure that bears no resemblance to the traditional models developed in the Mediterranean, Central European or Middle Eastern contexts, considering the variety contained in such vast and complex territories. On a territorial scale, the multitude of settlements constituted a non-hierarchical network of activity nodes linked by a network of roads running through the forest. This rhizomatic network supported the intense trade that existed between the different regions. On an urban scale, considering only the city itself, the first thing that stands out is the absence of a road structure that defines streets or arteries around which buildings and urban activity are concentrated. It should be borne in mind, in this respect, that the Maya never used the wheel or domestic animals for the transport of people or goods, which may make it more reasonable that they had no need to think about the layout of cities in relation to this function.

En su práctica totalidad, las ciudades de la civilización maya poseen una estructura urbana que no presenta ninguna analogía con los modelos tradicionales desarrollados en el contexto mediterráneo, centroeuropeo o de Medio Oriente, considerando la variedad contenida en tan extensos y complejos territorios. A escala territorial, la multitud de asentamientos constituían una red no jerarquizada de nodos de actividad unidos mediante una red de caminos que discurrían por la selva. Esta red rizomática servía de soporte para el intenso comercio que existía entre las diferentes regiones. A una escala urbana, considerando ya únicamente la ciudad en sí misma, lo primero que llama la atención es la ausencia de una estructura de viario que defina calles o arterias en torno a las cuales se concentren las edificaciones y la actividad urbana. Es necesario tener en cuenta, a este respecto, que los mayas nunca utilizaron la rueda ni animales domésticos para el transporte de personas o mercancías, lo que puede hacer más razonable el hecho de que no tuvieran la necesidad de pensar el trazado de las ciudades en relación a esta función.

How, then, were Maya cities defined? On the basis of the remains that have come down to us today, which have only been very partially analysed and interpreted, we can consider a series of fundamental urban and architectural elements or patterns in the genesis of the settlements. In the first place, we find the void. Due to the physical and environmental context strongly determined by a dense presence of tropical rainforest, every Maya urban structure begins with the definition of a void, of the opening of a clearing between trees. As we have previously commented, the Maya civilisation spread over territories that were essentially flat, where topographic unevenness did not acquire a relevant importance. Despite this, the development of urban life at different levels of height is recurrent in these cities. Thus, the fundamental act of structuring a Maya city is the modelling of the terrain to build a series of platforms and artificial plateaus on which the most important buildings of the city will be placed, i.e. those whose function is to represent the power of the ruling classes, the clergy and the aristocracy. Each of these platforms, some of which reached considerable extensions, served as a base for the construction of a multitude of buildings. These were connected to each other by complex systems of ramps and staircases which also ensured access from ground level. The urban structure is thus defined by a variable number of platforms of modelled terrain on which the main buildings are located, constituting nodes of urban activity. These stone-built plateaus define the primary order of Maya cities, functioning as an archipelago of islands intertwined with pre-existing nature. Around these platforms, a second order of buildings would develop, made of earth, wood and straw, destined to house the popular classes in the Mayan huts that have survived to the present day.

¿Cómo se definían, entonces, las ciudades mayas? A razón de los restos que han llegado a nuestros días, los cuales han sido analizados e interpretados solo muy parcialmente, podemos considerar una serie de elementos o patrones urbanos y arquitectónicos fundamentales en la génesis de los asentamientos. En primer lugar, nos encontramos con el vacío. Debido al contexto físico y ambiental fuertemente determinado por una densa presencia de selva tropical, toda estructura urbana maya comienza con la definición de un vacío, de la apertura de un claro entre árboles. Como hemos comentado previamente, la civilización maya se extendió por territorios que eran esencialmente planos, donde los desniveles topográficos no adquieren una importancia relevante. A pesar de esto, el desarrollo de una vida urbana a diferentes niveles de altura es recurrente en estas ciudades. Así, el acto fundamental de estructuración de una ciudad maya es el modelado del terreno para construir una serie de plataformas y mesetas artificiales sobre las que se dispondrán los edificios más importantes de la ciudad, es decir, aquellos cuya función es la representación del poder de las clases dominantes, el clero y la aristocracia. Cada una de estas plataformas, algunas de las cuales alcanzaban extensiones considerables, servía de base para la construcción de multitud de edificios. Estos se conectaban entre sí por complejos sistemas de rampas y escaleras que garantizaban además el acceso desde la cota de suelo. Nos encontramos pues con una estructura urbana definida por un número variable de plataformas de terreno modelado sobre las que se sitúan los edificios principales, constituyendo nodos de actividad urbana. Estas mesetas, construidas en piedra, definen el orden primario de las ciudades mayas, funcionando como un archipiélago de islas entrelazadas con la naturaleza preexistente. Alrededor de estas plataformas, se desarrollaría un segundo orden edificatorio, ejecutado con tierra, madera y paja, destinado a alojar a las clases populares en las cabañas mayas que han perdurado hasta nuestros días.

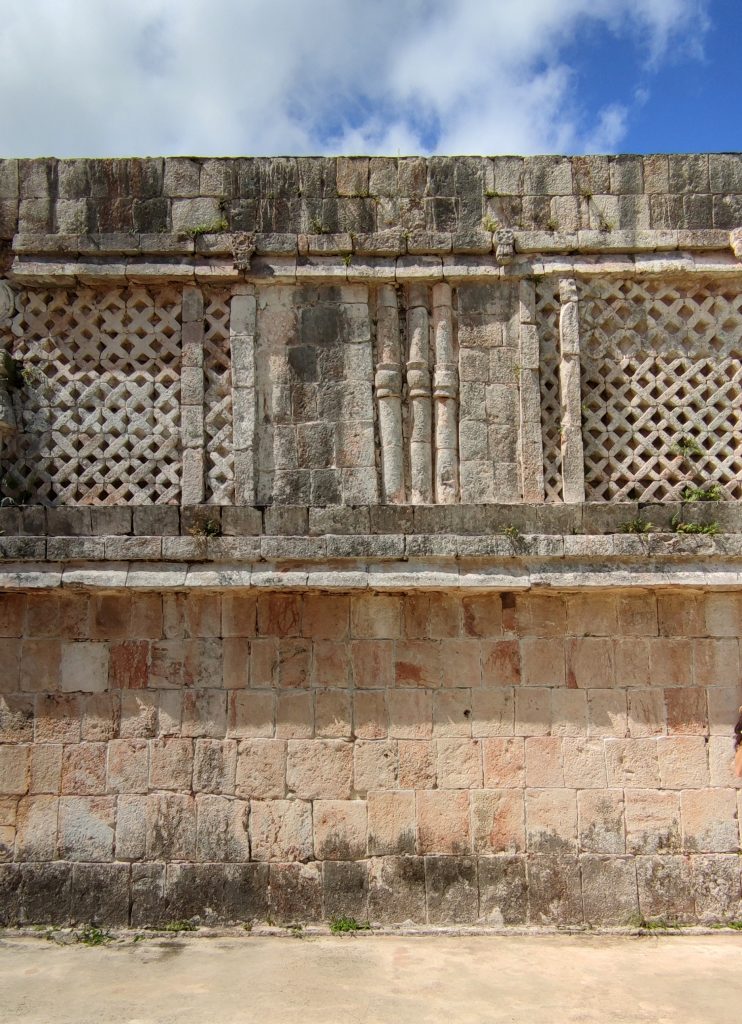

Similar to what happened in Ancient Greece or in Eastern cultures, a formal and compositional translation can be discerned from a humble architecture built in wood to one focused on transcending, and thus materialised in stone. Many of the compositional elements of Maya buildings, especially in Puuc cities such as Uxmal, are indebted to the systems of joints and dragging necessary in the thatched roofs of the huts. It could even be argued that the development of the cities on platforms of modelled terrain and stone is no more than a logical evolution of the foundations that, on a domestic scale, raise the humblest huts on an ever-wet ground.

De forma similar a como sucedió en la Antigua Grecia o en culturas orientales, se puede discernir una traslación formal y compositiva desde una arquitectura humilde construida en madera a una enfocada a trascender, y así materializada en piedra. Multitud de elementos compositivos de los edificios mayas, especialmente en ciudades Puuc como Uxmal, son deudores de los sistemas de uniones y arrastramientos necesarios en las cubiertas de paja de las cabañas. Se podría incluso argumentar que el desarrollo de las ciudades sobre plataformas de terreno modelado y piedra no es más que una evolución lógica de los basamentos que, a escala doméstica, levantan las cabañas más humildes sobre un firme siempre húmedo.

Operative Strategies

Following these premises, the discovered remains of the ancient Mayan city of Uxmal allow us to observe up to ten platforms. Some of them have a considerable extension, such as those that house the building complexes known as the Palace of the Governor, the Quadrangle of the Pigeons, the House of the Turtles, the Great Pyramid or the Pyramid of the Old Woman, to mention only the most relevant ones. It is estimated that, in times of greater prosperity, the city of Uxmal had a population of approximately 50,000 inhabitants, so the number of platforms could have been much higher. In addition to the aforementioned, we can recognise some of the platforms, with their building complexes, as some of the most notable examples of architecture bequeathed to us by the Maya civilisation.

Siguiendo estas premisas, los restos descubiertos de la antigua ciudad maya de Uxmal nos permiten observar hasta diez plataformas. Alguna de ellas goza de una considerable extensión, como las que albergan los conjuntos edificatorios conocidos como el Palacio del Gobernador, el Cuadrángulo de las Palomas, la Casa de las Tortugas, la Gran Pirámide o la Pirámide de la Vieja, por citar tan solo las más relevantes. Se estima que, en épocas de mayor prosperidad, la ciudad de Uxmal contó con una población aproximada de 50.000 habitantes, por lo que el número de plataformas podría haber sido mucho mayor. Además de lo ya mencionado, podemos reconocer alguna de las plataformas, con sus conjuntos edificatorios, como varios de los ejemplos más notables que nos legó la civilización maya en materia de arquitectura.

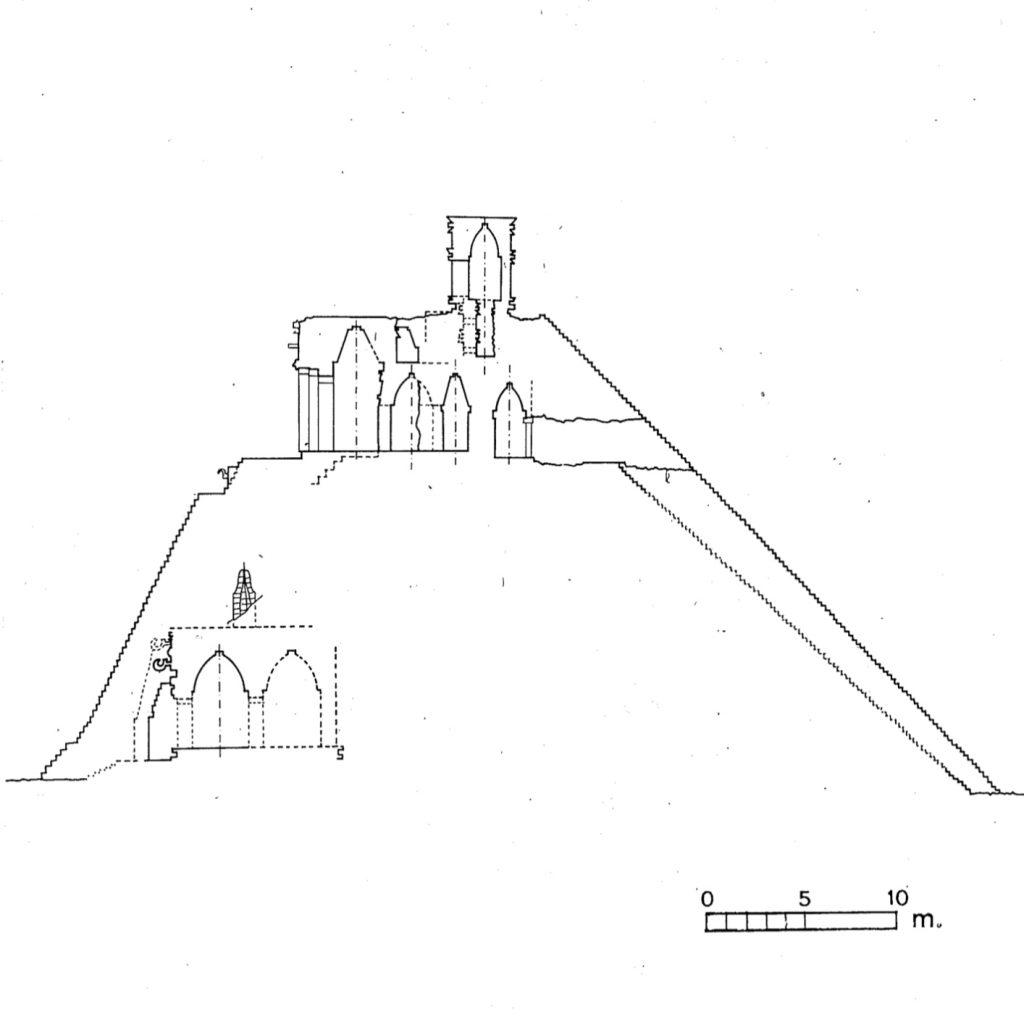

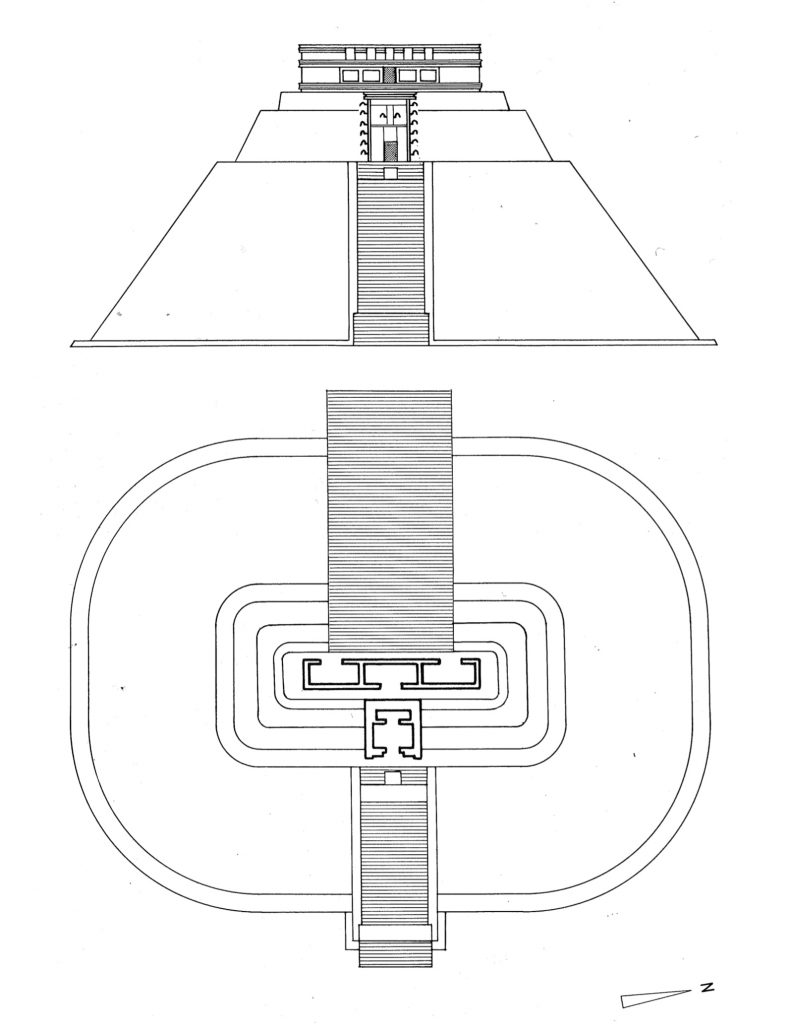

First of all, the Pyramid of the Soothsayer, in the easternmost part of Uxmal, is the paradigmatic case where we can observe one of the architectural and constructive concepts of the Maya tradition: the concept of superposition. With gently rounded corners, this pyramid, almost forty metres high, would have been built in five different construction phases. In each of these phases, an extension was built on top of the original state. By the addition of mass of material and the consequent growth in height and volume, the Pyramid of the Soothsayer would have grown upon itself without demolishing the previous phases, simply burying them, thus including them as foundations of the new state. We can thus conclude, by applying a prospective view, that each building is the germ that defines the structure and the laws necessary for its probable future evolution, always carried out on the basis of addition operations that result in the growth of the built mass. In this case, different temples were hidden inside the structure of the final state of the temple of Uxmal, and access to them has been possible in a very restricted manner for their study through excavations and punctual perforations.

En primer lugar, la Pirámide del Adivino, en la parte más oriental de Uxmal, es el caso paradigmático donde podemos observar uno de los conceptos arquitectónicos y constructivos de la tradición maya: el concepto de superposición. De esquinas suavemente redondeadas, esta pirámide de casi cuarenta metros de altura se habría desarrollado en cinco fases diferentes de construcción. En cada una de ellas, una ampliación se ejecutó sobre el estado original. Mediante el añadido de masa de material y el consecuente crecimiento en altura y volumen, la Pirámide del Adivino habría crecido sobre sí misma sin derribar las fases anteriores, simplemente sepultándolas, incluyéndolas así como cimientos del nuevo estado. Podemos concluir así, aplicando una mirada prospectiva, que cada edificio es el germen que define la estructura y las leyes necesarias para su probable evolución futura, realizada siempre a base de operaciones de adición que devienen en un crecimiento de la masa edificada. En este caso, diferentes templos quedaron ocultos en el interior de la estructura del estado final del templo de Uxmal, habiendo sido posible el acceso a ellos de manera muy restringida para su estudio mediante excavaciones y perforaciones puntuales.

This would undoubtedly be the most obvious case, but we can find other architectural strategies related to this concept of superimposition. While maintaining the original state of the existing structures, the Mayans evolved their buildings by adding chambers or rooms, as well as incorporating porticoed galleries in front of the temples, thus extending the covered space over the previously modelled platforms.

Éste sería sin duda el caso más evidente, pero podemos encontrar otras estrategias arquitectónicas relacionadas con este concepto de superposición. Manteniendo siempre el estado original de las estructuras existentes, los mayas evolucionaron sus edificios mediante el añadido de crujías de cámaras o habitaciones, además de incorporar galerías porticadas frente a los templos, extendiendo así el espacio cubierto sobre las plataformas previamente modeladas.

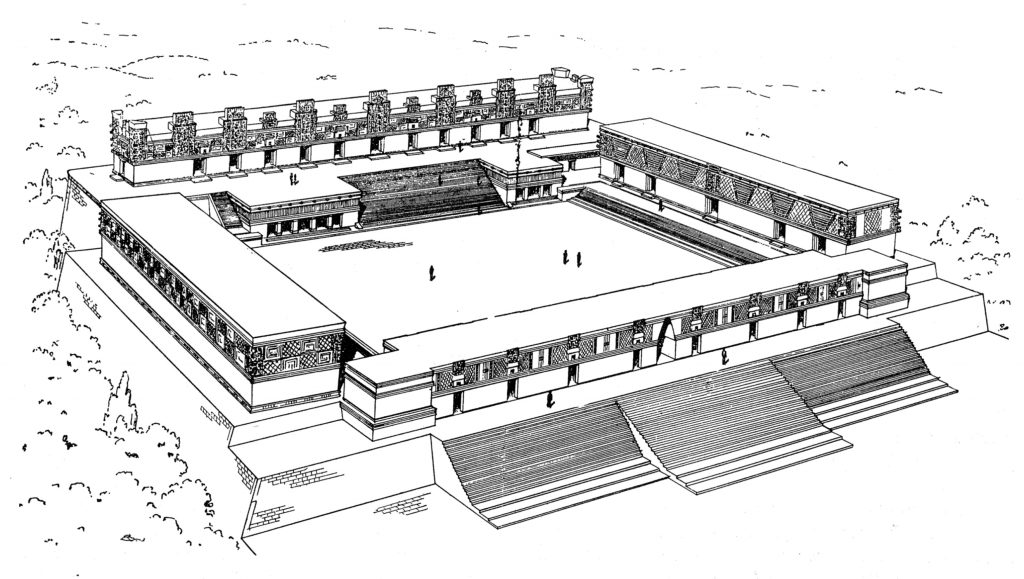

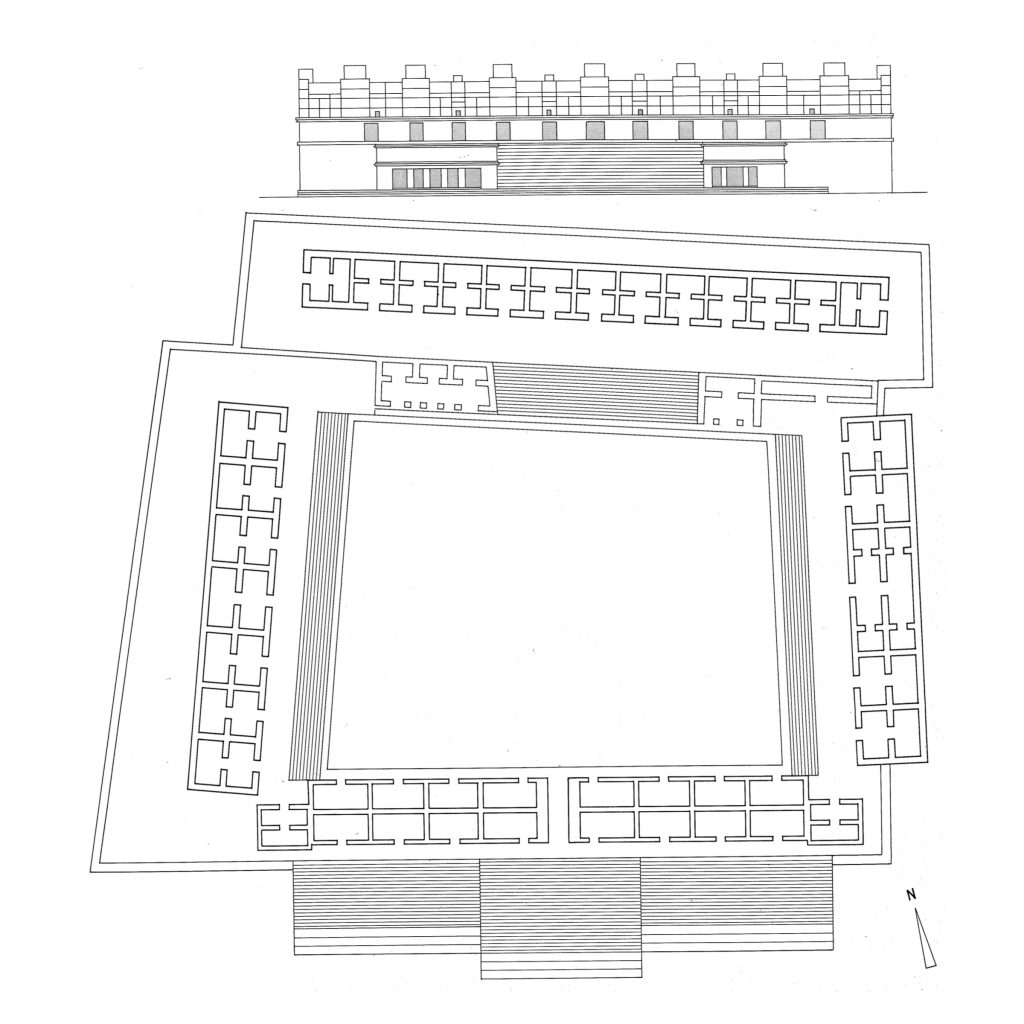

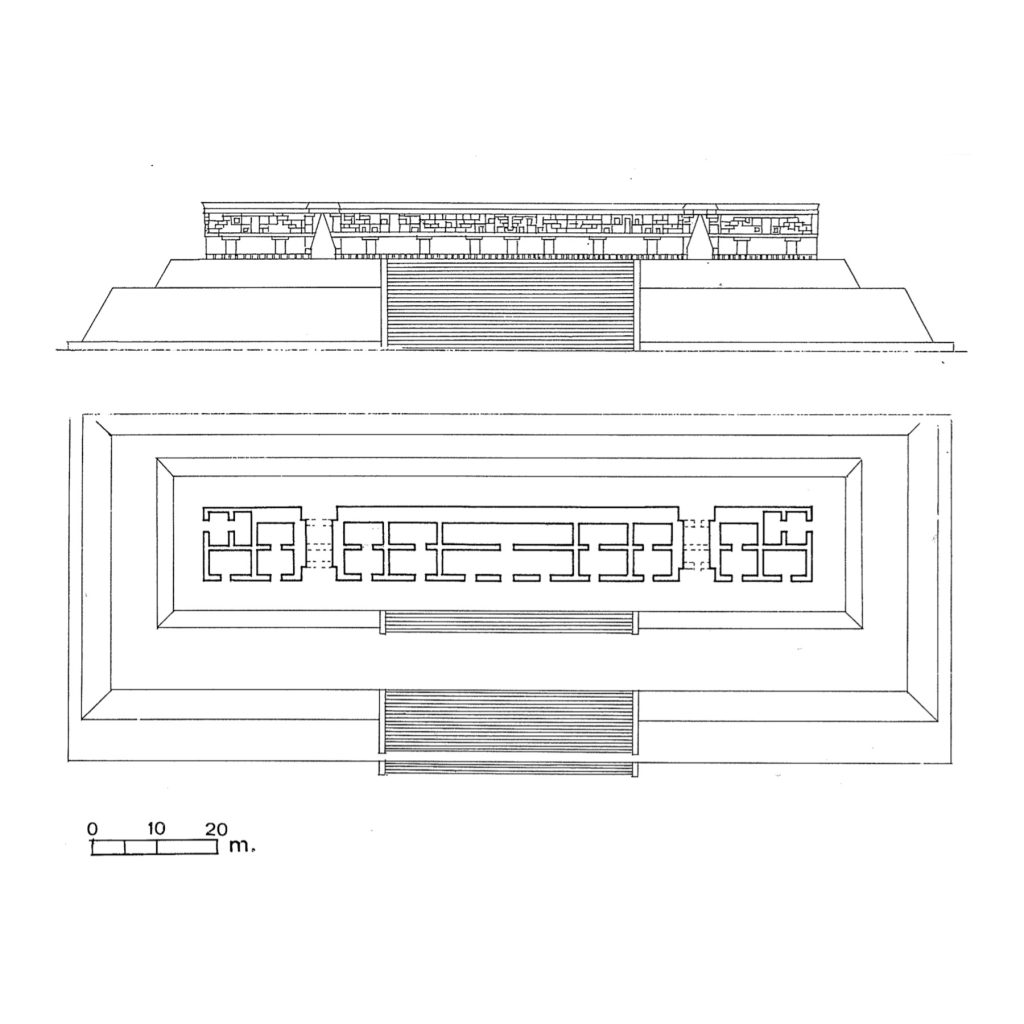

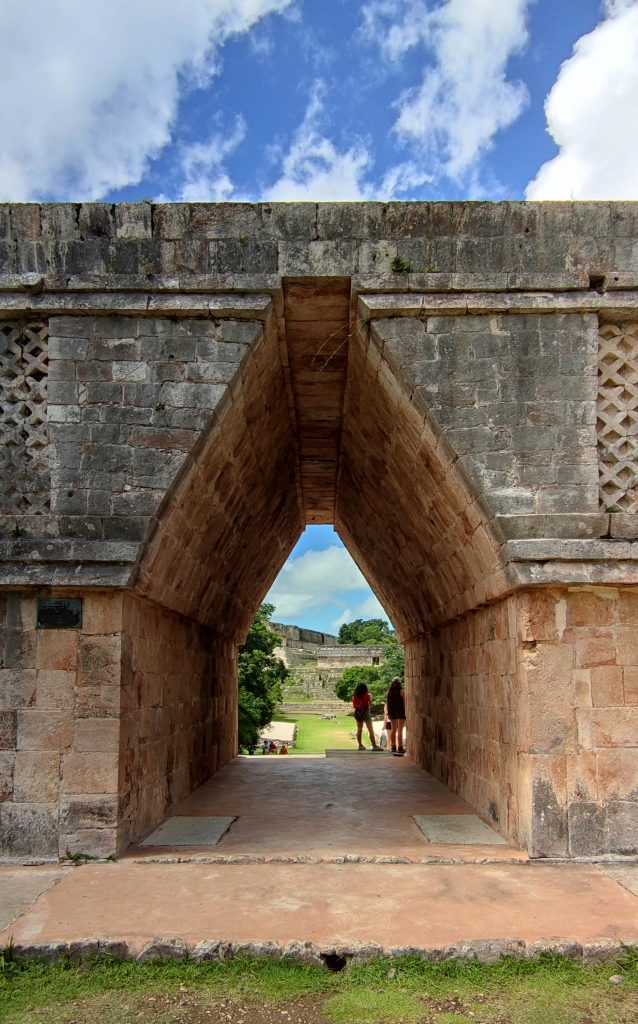

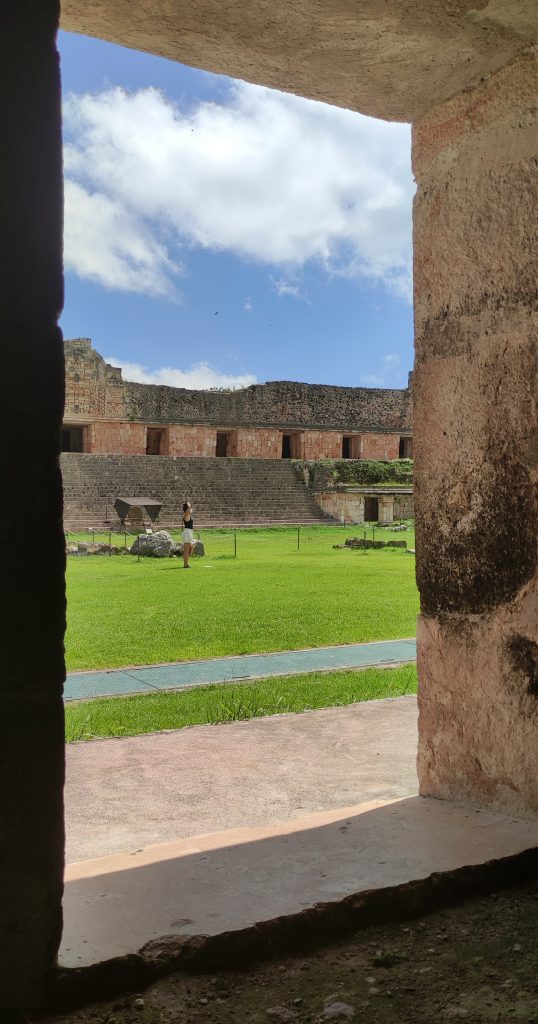

Among the group of built platforms at Uxmal, the Quadrangle of the Nuns stands out for its spatial complexity, so called by the first settlers due to its spatial similarity to the cloistered typology typical of European convents. Raised on a platform which is accessed by different systems of stairs, a large open space of rectangular proportions is flanked by four buildings, so that each of them defines the limits of the quadrangle without joining, leaving the four vertices always open. Thus, despite being a fully urbanised space, the surrounding jungle filters into its interior through these openings, establishing a balanced combination between architecture and landscape, a fundamental characteristic of Mayan architecture. Accessed through the triumphal arch, located on the south side, and in clear relation to the platforms of the Ball Court and the Governor’s Palace, one can appreciate the refined compositional work developed by the Maya architects in this complex. Far from composing a static and heavy ensemble, the alternation between volumes of different heights, the different stairways and steps giving access to the upper platforms or the openings of openings and porticoed galleries are resources which, together with the decision to keep the corner meetings open, make it possible to define a highly dynamic exterior space without renouncing its physical and visual delimitation. The internal spatial structure of the buildings, based on parallel bays of small chambers, suggests that they housed the dwellings or offices of high-ranking officials or clerics, who would find in the open space of the quadrilateral the necessary agora which, perhaps, fulfilled the assembly space function of Mayan society.

En el conjunto de plataformas edificadas de Uxmal, destaca por su complejidad espacial el Cuadrángulo de las Monjas, denominado así por los primeros colonos debido a su similitud espacial con la tipología claustral propia de los conventos europeos. Elevado sobre una plataforma a la cual se accede mediante distintos sistemas de escaleras, un gran espacio abierto de proporciones rectangulares está flanqueado por cuatro edificios, de forma que cada uno de ellos define los límites del cuadrilátero sin unirse, dejando los cuatro vértices siempre abiertos. Así, a pesar de ser un espacio plenamente urbanizado, la selva circundante se filtra a su interior a través de estas aperturas, estableciendo una equilibrada combinación entre arquitectura y paisaje, característica fundamental de la arquitectura maya. Accediendo a través del arco triunfal, situado en la cara sur, y en clara relación con las plataformas del Juego de Pelota y del Palacio del Gobernador, se puede apreciar el refinado trabajo de composición que desarrollaron los arquitectos mayas en este conjunto. Lejos de componer un conjunto estático y pesado, la alternancia entre volúmenes de diferentes alturas, las diferentes escaleras y gradas que dan acceso a las plataformas superiores o las aperturas de huecos y galerías porticadas son recursos que, junto a la decisión de mantener los encuentros en esquina abiertos, permiten definir un espacio exterior de gran dinamismo sin renunciar por ello a delimitarlo física y visualmente. La estructura espacial interna de los edificios, a base de crujías paralelas de pequeñas cámaras, hace suponer que albergasen viviendas u oficinas de altos funcionarios o clérigos, que encontrarían en el espacio abierto del cuadrilátero el ágora necesario que, quizá, cumpliese la función espacio asambleario de la sociedad maya.

Infrastructural Nature

The study of Maya urban settlements and the architectural elements of which they are composed, leaving aside stylistic, compositional or historiographical interpretations, can offer an operational perspective of the discipline of great interest and in relation to certain concepts or strategies more typical of Modernity. The urban structure of Maya cities, with their array of elevated platforms that act as condensers or nodes of activity, bears a striking resemblance to models of satellite city, archipelago city or even rhizomatic structures. The infrastructural nature of these platforms, which ensured evolution and growth on them, allowed Maya settlements to evolve with great flexibility. Furthermore, urban development on the basis of two building orders is evidence of the Maya’s concern with the concept of time as applied to architecture. The first of these orders was destined to last as a manifestation of the power of the ruling classes, and was thus materialised in stone. The second order, executed in wood and thatch to house the popular classes, constitutes the truly urban fabric that extended into the transitional spaces between the platforms and the jungle. The importance of time as a design tool would also be present in the operations of growth by superimposing matter and mass that they developed to extend their buildings, always starting from the germ of the existing. This strategy, very similar to the modern idea of organic growth in small doses developed by Christopher Alexander, defines the evolutionary and open to change nature of the Maya city.

El estudio de los asentamientos urbanos mayas y los elementos arquitectónicos que los componen, dejando de lado las interpretaciones estilísticas, compositivas o historiográficas, puede ofrecer una perspectiva operativa de la disciplina de gran interés y en relación a determinados conceptos o estrategias más propios de la Modernidad. La estructura urbana de las ciudades mayas, con su conjunto de plataformas elevadas que actúan como condensadores o nodos de actividad, se asemeja notablemente a modelos de ciudad satélite, ciudad archipiélago o incluso estructuras rizomáticas. La naturaleza infraestructural de estas plataformas, que garantizaban la evolución y el crecimiento sobre ellas, permitía que los asentamientos mayas pudieran evolucionar con gran flexibilidad. Además, el desarrollo urbano a partir de dos órdenes constructivos evidencia la preocupación de los mayas por el concepto de tiempo aplicado a la arquitectura. El primero de estos órdenes estaría destinado a perdurar como manifestación del poder de las clases dominantes, siendo así materializado en piedra. El segundo orden, ejecutado en madera y paja para alojar a las clases populares, constituye el tejido verdaderamente urbano que se extendía en los espacios de transición entre plataformas y selva. La importancia del tiempo como herramienta de proyecto estaría presente, además, en las operaciones de crecimiento por superposición de materia y masa que desarrollaron para ampliar sus edificaciones partiendo siempre del germen de lo existente. Esta estrategia, muy similar a la idea moderna de crecimiento orgánico a pequeñas dosis, desarrollada por Christopher Alexander, define la naturaleza evolutiva y abierta al cambio de la ciudad maya.

Further Reading:

Stierlin, Henri. “Architecture of the World. Mayan”. Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH

Gendrop, Paul. Heyden, Doris. “Arquitectura Precolombina”. Aguilar, 1989

Alexander, Christopher. “Tres Aspectos de Matemática y Diseño; La Estructura del Medio Ambiente”. Tusquets, 1980