This article is part of Ungreen, a series curated by Hidden Architecture where we attempt to create a resistance against some of the dogmas assimilated within contemporary discourse that sustainable architecture has to be “green”. We want to recover the ancestral knowledge that was shared among generations throughout history of humanity and defines how urban settlements have adapted to its weather conditions.This knowledge, inherent to vernacular architecture has been often used by modern or contemporary architectural practices to create new techniques or construction systems.

Este artículo es parte de Ungreen, una serie comisariada por Hidden Architecture donde tratamos de crear una resistencia contra algunos de los dogmas asimilados en el discurso actual que claman que la arquitectura sostenible tiene que ser verde. Queremos recuperar el conocimiento ancestral que ha sido heredado a través de generaciones a lo largo de la historia de la humanidad y que define como los asentamientos urbanos se han ido adaptando a sus condiciones climáticas. Este conocimiento, manifestado en la arquitectura vernácula se ha filtrado en ocasiones a prácticas arquitectónicas modernas o contemporáneas, evolucionado hacia nuevas técnicas o sistemas constructivos

***

Region: Iceland (similarities with other Turf houses in Nordic areas such as Norway, Faroe Islands or the Scottish Islands)

Example: The Farmhouse, Þjóðveldisbærinn. Iceland

***

Owing to the lack of suitable clay for the production of roof tiles, roofs have been covered with peat since Iceland’s settlement in the 9th century. Grass grows on the peat roofs and the ensuing dense network of roots forms an interwoven, water-repellent layer, which is adequate waterproofing in areas with low rainfall (approx. 500 mm p.a.). However, the durability of the waterproofing function is directly dependent on the pitch of the roof. If it is too steep, the rainwater drains too quickly, which means the peat dries out and develops cracks during periods of little rainfall. On the other hand, if the pitch is too shallow, the water seeps through. The peat also regulates the moisture level and assumes various storage functions.

Ante la escasez de un barro adecuado para la fabricación de tejas y ladrillos, los tejados se recubrieron con turba (ya desde la colonización del país en el siglo IX ). Sobre los tejados crece hierba que, con sus espesas raíces, forma una capa enmarañada que actúa como barrera de protección impermeable en regiones con muy escasas precipitaciones (alrededor de 500 mm/ año). La duración de la capacidad impermeabilizante depende directamente de la pendiente de la cubierta. Si ésta está demasiado inclinada, el agua fluye tan deprisa que la turba comienza a secarse en los periodos de escasas lluvias y el tejado se agrieta. Si, por el contrario, la cubierta es excesivamente plana, el agua se filtra al interior. Además la turba regula la humedad y asume diversas funciones de acumulación.

Desplazes, Andrea (Ed). (2005). ‘Constructing architecture’. Extract from page 156. (Spanish version in page 176)

The construction of houses with walls and roofs made with turf was a system developed in Iceland when the first human settlements arrived at the island during the ninth century. It was regularly used until the beginning of twentieth century with the arrival of modern materials and construction systems such as reinforced concrete. The construction technique was brought from Norway by the first Vikings who came to the island. There was a lack of constructive materials such as wood or stone in the island. Nonetheless, it was very easy to extract turf from different Icelandic marshes. This caused a development of this system throughout the island for more than thousand years.

La construcción de casas con muros y cubiertas realizados en turba fue un sistema que se desarrolló en Islandia desde el siglo IX con los primeros asentamientos humanos en la isla hasta principios del siglo XX con la llegada del hormigón. La técnica constructiva fue traída desde Noruega por los primeros vikingos que llegaron a la isla. Ante la falta de materiales constructivos tales como la madera o la piedra y la facilidad para extraer turba de las diferentes marismas islandesas provocó un desarrollo de este sistema en toda la isla durante más de mil años.

Unlike Norway or other Nordic countries, this type of construction was used by all social classes on Iceland. The only difference in the architecture between wealthy classes and houses for poor people was the type of finishes inside the houses. Nonetheless, the construction system was always the same. Therefore, for this article of the UNGREEN series, we will describe the system based on Iceland architectural examples. To provide a global perspective of the Traditional Turf Houses, we are dividing the article in the following sections: Architectural typologies built with peat; the construction system and its different transformations; and its thermal and energetic properties. We are finishing the article exposing some considerations about its landscape and spatial possibilities.

A diferencia de Noruega u otros países nórdicos, este tipo de construcciones fue utilizada por todas las clases sociales en la isla. La diferencia entre las clases más acomodadas y las más desfavorecidas fue la calidad de los acabados en el interior de las casas, siendo el sistema constructivo similar para todas ellas. Por tanto centraremos este artículo de nuestra serie UNGREEN en la descripción de este sistema asociado a la arquitectura islandesa. Para poder ofrecer una perspectiva global de este tipo de construcciones, dividiremos el artículo en las siguientes secciones: Tipologías arquitectónicas asociadas con la turba; el sistema constructivo y sus distintas transformaciones; y sus propiedades térmicas y energéticas. Terminaremos el articulo ofreciendo unas breves consideraciones sobre sus posibilidades paisajísticas y espaciales.

TYPOLOGY | TIPOLOGÍAS

Originally, this type of constructions had a rectangular shape creating long and narrow spaces. They had a heavy roof and they did not have windows to bring natural light inside. In the center of the room, there was an opening to light a fire to heat the interior. This slot ran parallel to the longitudinal façade and through the entire room. The access door was originally located in the long side of the house but, later, some constructions stared to change the access to its short side to create a symmetry to the access to the house.

Originalmente la forma de estas construcciones era rectangular creando espacios interiores largos, estrechos y con poca luz debido a la falta de ventanas y pesadez de la cubierta. En el centro de la estancia había una apertura para encender un fuego que calentase el interior. Esta ranura iba en paralelo a la fachada longitudinal extendiéndose por todo el interior. La puerta de acceso inicialmente solía colocarse en uno de sus laterales pero ciertas construcciones comenzaron a localizar sus accesos en sus fachadas más cortas provocando una simetría en el acceso a la vivienda.

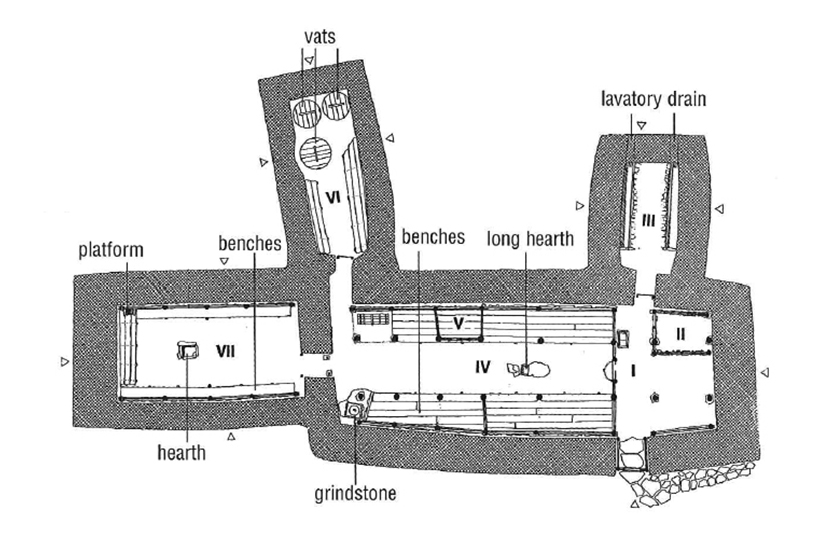

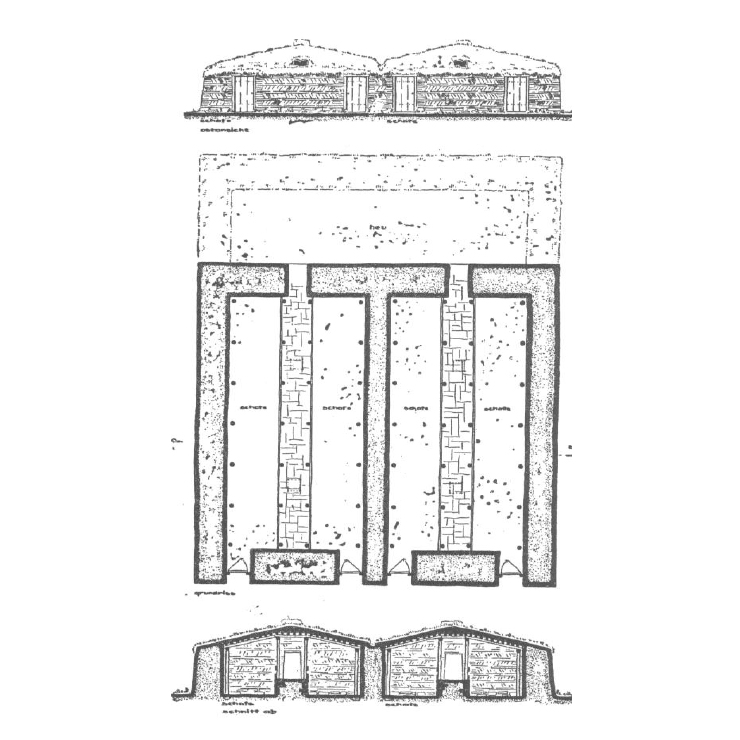

This simple typology evolved through time with the addition of different constructions to the original room. The following project, the farm of Þjóðveldisbærinn Stöng (construction that was abandoned in 1104 and was reconstructed in 1977), had two additional constructions on its long facades and another addition on its back. It created different rooms for different functions.

Esta tipología sencilla fue evolucionando con el paso del tiempo mediante la adición de distintas construcciones a la estructura original. En el caso mostrado a continuación, la granja de Þjóðveldisbærinn Stöng (construcción se abandonó en 1104 y volvió a reconstruirse en 1977), a la construcción original se le añaden dos cuerpos en uno de sus laterales y otro más en su parte posterior creando distintas habitaciones para distintas funciones.

During the middle age, the expansion of these houses was made through the connections of small houses that were connected transversally through a central corridor or gangabær. The Folk Musuem Glaumbær, show below follows this typological alteration.

Durante la edad media la expansión de estas casas se realizó mediante la conexión de casas más pequeñas unidas transversalmente a través de un pasillo central o gangabær. El museo Folk Glaumbær, mostrado a continuación, sigue esta alteración tipología.

CONSTRUCTION SYSTEM | SISTEMA CONSTRUCTIVO

The main material of this constructive system is the peat, a dark brown color soil which is extracted from the marshes of Iceland. It is created by the putrefaction of plant material when it gets in contact with acid water.

El material principal de este sistema constructivo es la turba, un tipo de tierra de color pardo oscuro, que se extrae de las marismas de Islandia y se produce por la putrefacción de materia vegetal en contacto con agua ácida.

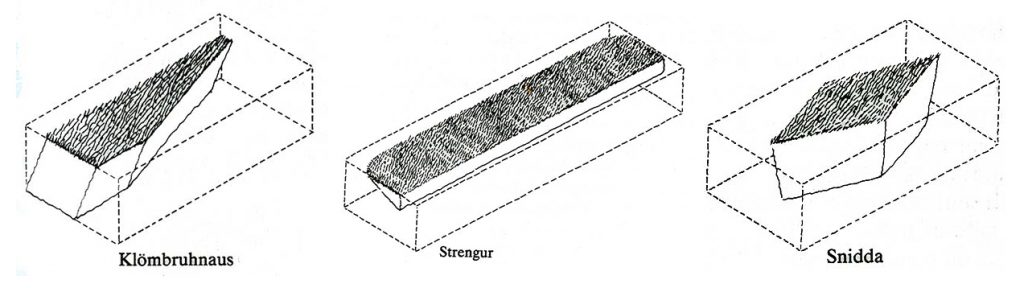

There are two types of ways to extract the peat from the marshes. The first one is the Strengur, that cuts pieces of one meter (three feet) of length by five or 10 centimeters (two or three inches) of width. These pieces are used to build masonry walls that cut stand by themselves or alternated with layers of stone. The type of cut is the klömbruhnaus, peat blocks that are cut with a diamond form with the approximate following dimensions: 20-centimeter-long (8 inches), thirty centimeters high (one foot) and sixty-centimeter-long (two feet). A variation of the cut klömbruhnaus is the cut Snidda that can be used to build walls and sometimes roofs. When the peat is extracted from the marshes, this is very wet so it has to be dried before it can be used. This is the only form it can work as a thermal insulation element.

Hay dos tipos de corte para poder extraer la turba de las marismas. El primero de ellos es el corte Strengur, que consiste en piezas de un metro de largo por cinco o diez centímetros de ancho. Este tipo de corte se utiliza para construir muros por apilamiento de estos cortes o intercalándolos con capas de piedra. El otro corte tipo es el klömbruhnaus, unos bloques de turba cortados con sección en forma de diamante de veinte centímetros de ancho por treinta de alto y una longitud de 60 centímetros aproximadamente. Una variación del corte klömbruhnaus, es corte tipo Snidda, que se puede usar para construir muros y en algunos casos cubierta. Al extraer la turba de las marismas, ésta se encuentra en un estado muy húmedo. Es por ello por lo que necesite ser secada antes de usarse para que funcione como elemento de aislamiento térmico.

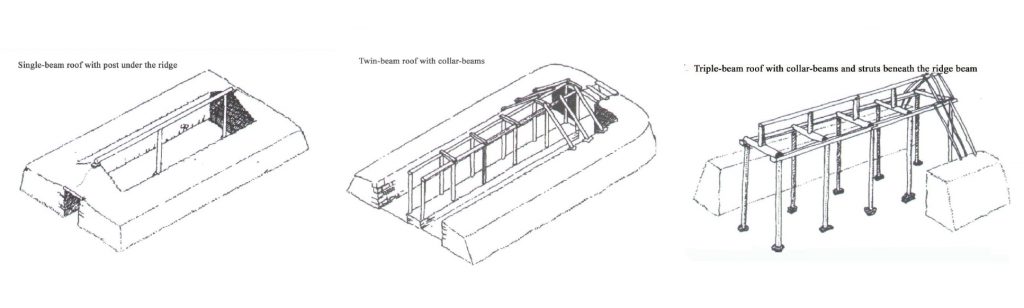

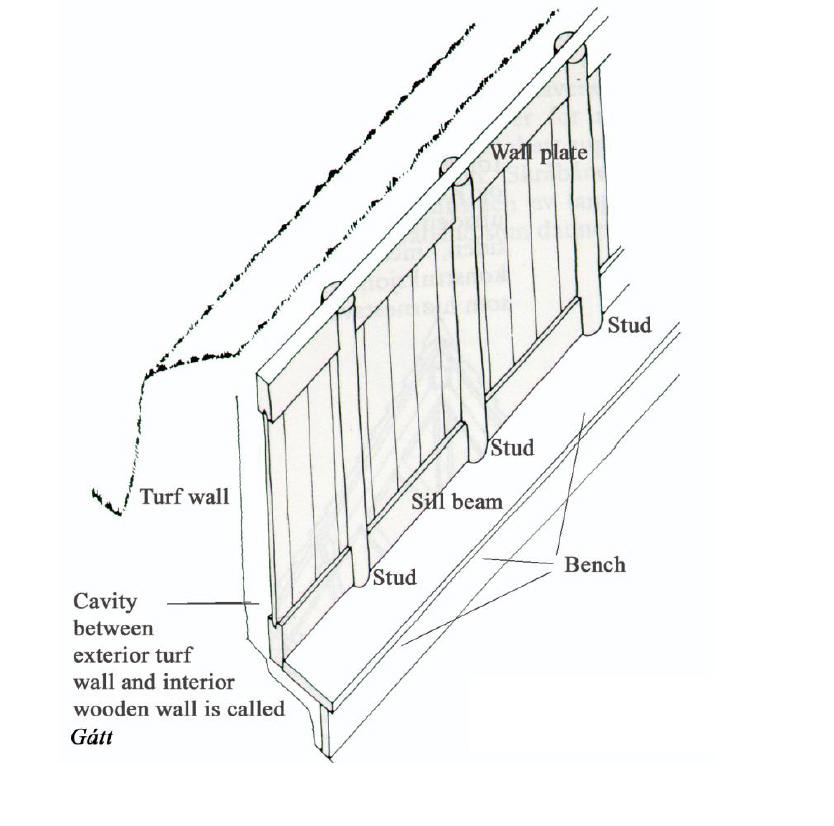

A wood structure supports the turf material. As the wood is a scarce material in Iceland, its use is reduced to its necessities. The best form to distinguish the rich houses from wealthy social class was by the use of wood. They had wood beyond its basic necessities, both in the structure and in the interior finishes (floors and walls). In the following diagram, we can see three different wood structural systems: a simple beam or a double or triple beam depending on the span of the room. Sometimes habitants also built small sheds without any wood structure by using peat vaults. Its size and spatial quality is very limited. Therefore, we are not detailing its architectural or structural conditions.

Las secciones de turba se apoyaban sobre una estructura de madera. Como la madera es un material escaso en Islandia, su uso se reducía al mínimo. Es así como se pueden reconocer las casas de las clases altas por un uso de la madera más allá del necesario tanto en la estructura como en los propios acabados interiores (muros y suelo). Sin entrar en detalles estructurales, podemos ver en el siguiente diagrama como había tres tipos de sistemas estructurales de madera: con una viga simple, doble o triple en función de la luz que se deseaba alcanzar dentro de la casa. Algunas veces se construyeron pequeños cobertizos únicamente mediante bóvedas de turba sin ningún tipo de estructura de madera. Tanto su tamaño como calidad espacial es muy limitada por lo que no entraremos a detallarlos.

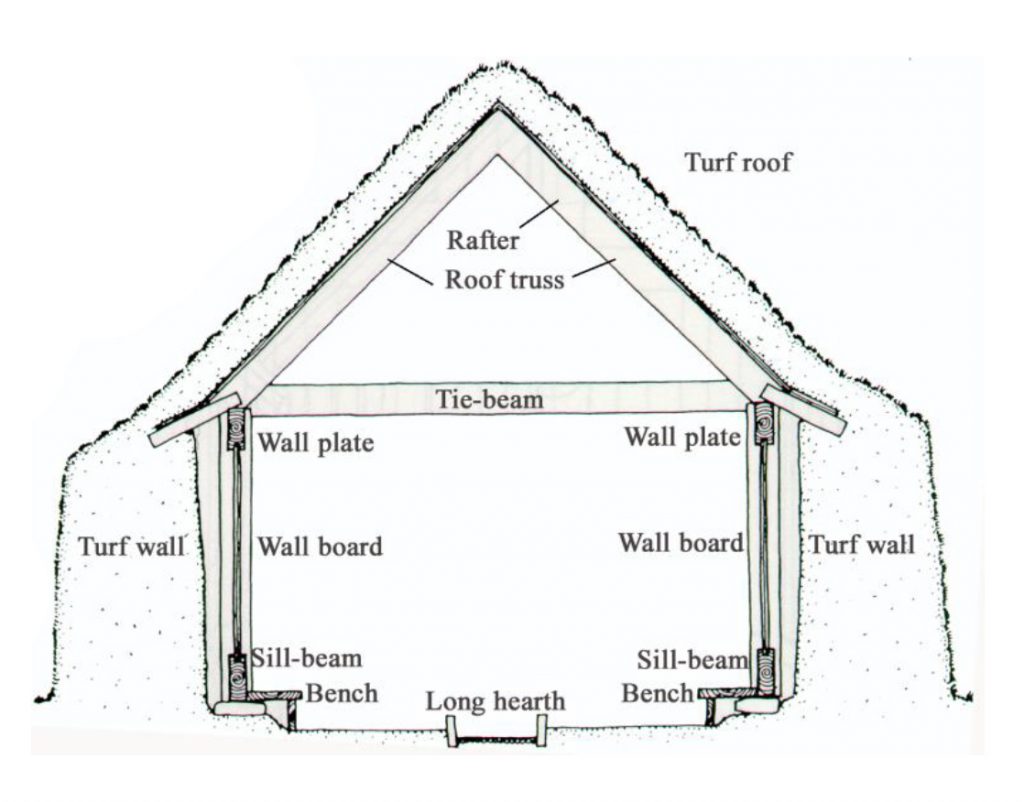

The roof is built with the following layers from the inside out: The main wood structure supports a first layer of peat that is completely dry. It is connected to the structure through a small wood substructure that allow air to flow between both materials and the main structure does not rot in contact with the peat. Second, there is a series of waterproofing birch bark sheets that prevent from any filtration to the interior. On the exterior face, there is a second layer of peat that remains wet almost the entire year. Grass grow from this layer of peat. Moreover, as Andrea Desplazes explain in his book Constructing architecture, the slope of the roof cannot be very flat to avoid leaks in the interior space or too sloped so water would runoff very fast and the peat would easily dry.

De adentro hacia afuera la cubierta se construye con las siguientes capas: La estructura de madera principal soporta una primera capa de turba prácticamente seca. Esta se conecta a dicha estructura principal a través de una pequeña subestructura, también de madera que permite que el aire fluya entre los dos materiales y la estructura principal no se pudra con el contacto con la turba. A continuación se colocan una serie de láminas impermeables de corteza de abedul que evitan filtraciones al interior. En el exterior hay una segunda capa de turba que permanecerá húmeda casi todo el año y desde donde crecer el césped de manera natural. Además como explica Andrea Desplazes en su libro Construir Arquitectura, la pendiente de la cubierta no puede ser ni demasiado plana, para evitar filtraciones al interior de la vivienda, ni demasiado inclinada para evitar una escorrentía muy rápida y que la turba se seque.

Walls usually built directly on the ground or using a stone basement when the house had a special value. It is built with two layers of peat with an air space in between to drain water from the roof. The interior peat wall of the houses is wrapped by wood planks that hold the turf blocks and created in the base a small bench through the entire perimeter. The wall peat wall was made using the klömbruhnaus cut, and the wall is shown with a very specific texture, similar to regular stone wall.

Por su parte los muros solían construirse directamente sobre el terreno o sobre una base de piedra cuando la casa tenía un valor añadido. Su constitución se crea a partir de dos capas de turba con un espacio intermedio recubierto de piedras desde donde se evacua el agua drenada desde la cubierta. El muro interior de las casas se recubría de listones de madera que sostenían los bloques de turba y creaban en su base un pequeño banco para sentarse en su perímetro. Respecto al exterior, cuando se usaba la turba con el tipo de corte klömbruhnaus, el muro aparece con una textura muy característica similar a un muro de piedras regulares.

ENERGY, THERMAL PROPERTIES | ENERGÍA, PROPIEDADES TÉRMICAS

Turf houses achieve very easily the thermal comfort of an Icelander (around 18 o 19° C). When the peat is dry, its insulating capacity is around 80% of a conventional thermal insulation. This percentage is reduced to 20% when the peat moistens. However, the peat walls are several meters thick, so the thermal property is normally enough. Moreover, peat walls have adiabatic properties (they do not transfer heat with the environment). In addition, the morphology of the houses with soft sloping roofs, similar to a slope, protect the houses against wind.

Las construcciones de turba alcanzan de manera muy sencilla el confort térmico de un islandés (alrededor de los 18 o 19 grados). Cuando la turba está seca, su capacidad aislante es alrededor de un 80% de un aislante térmico convencional. Este porcentaje se reduce hasta el 20% de capacidad térmica cuando la turba se humedece. No obstante, los muros de turba tienen varios metros de grosor por lo que la capacidad aislante es suficiente y tienen un comportamiento adiabático (no transfieren calor con su entorno). Además, la morfología de las casas, con techos inclinados suaves, similares a los de una colina, protegía a las casas frente al viento.

Moreover, when the interior face was finished with wood, a material with low thermal conductivity, the interior spaces could be easily heated. It was usually heated with a fireplace in the middle of the room.

Por otro lado, al recubrir su interior con madera, un material con una difusividad térmica muy baja, los interiores podían ser calentados muy fácilmente, normalmente con un fuego en el medio de la casa encendido a base de estiércol.

Peat usually degraded over the years and walls and roof had to be rebuild after some time. In most of the houses, inhabitants rebuilt the peat walls and kept the wood structure and timber finishes if they were not damaged. In the south of Iceland where the climate fluctuation is stronger, peat had to be changed every 20 or 25 years. In the north, there is a more stable climate and turf houses had to be rebuilt every 50 or 70 years.

Normalmente la turba se degradaba con el paso de los años y los muros y las cubiertas tenían que rehacerse pasado un tiempo. La mayoría de las veces se rehacían los muros de turba manteniendo la estructura y la mayoría de los interiores de madera que no habían sido dañados. En el sur de la Islandia donde la fluctuación del clima es más fuerte, la turba debía ser cambiada cada 20 o 25 años. En el norte, al tener un clima más estable la turba debía ser cambiada cada 50 o 70 años.

LANDSCAPE & INTERIOR SPACE | PAISAJE Y ESPACIO INTERIOR

From a phenomenological approach, turf constructions have a spatial contradiction between interior and exterior. This type of constructions integrates within the natural landscape and, at the same time, they are able to modify it creating artificial topographies. This creates a wide range of design opportunities to create new topographies within an architectural project. Nonetheless, the interior space of the turf houses is very poor and limited. This was one of the reasons people stopped to use them when reinforced concrete was imported into Iceland. The massive structural character of these constructions makes very difficult to create openings to bring natural light and ventilation into the interiors. This a very important factor in Iceland because there is a lack of natural light in winter. Nowadays, it is possible to offer a contemporary approach to this construction material as several architectural offices are doing in Iceland such as Studio Granda or PKdM Arkitekta. They are combining turf with glass or wood to reduce the oppressive interiors.

Desde el punto de vista fenomenológico, las construcciones de turba sufren una contradicción espacial entre el interior y el exterior. Este tipo de construcciones se difuminan e integran dentro de un paisaje natural y al mismo tiempo se puede modificar el paisaje, la topografía creando colinas artificiales. Esto genera unas posibilidades proyectuales muy amplias que pueden ser utilizadas para crear nuevas condiciones de topografías en un proyecto arquitectónico. No obstante, el espacio interior que crean las casas de turba es muy pobre y limitado, una de las razones por las que dejaron de usarse al llegar el hormigón armado a Islandia. El carácter estructural masivo de estas construcciones dificulta la apertura para traer luz natural y ventilar los interiores, un problema muy grave en un clima como el de Islandia en el que apenas hay luz durante los inviernos. No obstante, se puede ofrecer una aproximación contemporánea a este material constructivo como están haciendo estudios islandeses como Studio Granda o PKdM Arkitektar donde introducen materiales tales como el vidrio o la madera para acompañar a la turba y reducir la sensación opresiva que generan sus interiores.

In addition, this kind of vernacular architecture creates many keys to understand the thermal behavior of a space with the use of massive soil (peat, in this case) in a semi-buried space. Moreover, using materials from the same region generates a consequent energy saving since materials have not to be transported long distances. Turf houses achieve with one same construction system a thermal and formal optimization. Moreover, they take advantage of accessible natural resources in Iceland.

Además, este tipo de arquitectura vernácula genera muchas claves para poder entender el comportamiento térmico de un espacio mediante el uso de un masivo de la tierra (en este caso la turba) en un espacio semienterrado, y usando materiales del mismo lugar de construcción, con el consecuente ahorro energético que conlleva al no tener que transportar materias primas largas distancias. Las casas de turba consiguen dentro de un mismo modelo constructivo una optimización térmica, formal y de recursos materiales accesibles en un lugar específico como es Islandia.

Drawings extracted by http://www.glaumbaer.is/static/files/Skjol/xvi-traditional-building-methods.pdf

Bibliography:

– Desplazes, Andrea (Ed). (2005). ‘Constructing architecture’

-Neila González, F. Javier (Ed). (2015) ‘Miradas Bioclimáticas a la Arquitectura Popular del Mundo’

– THJODVELDISBAER http://www.thjodveldisbaer.is/en/about-thjodveldisbaeinn/

– Unesco https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5589/

– Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peat