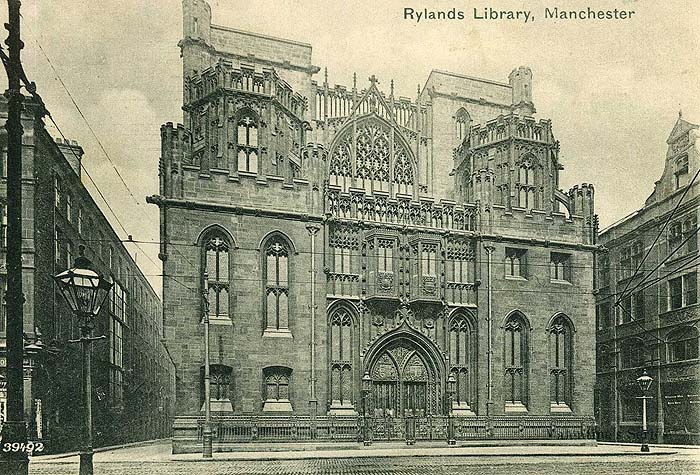

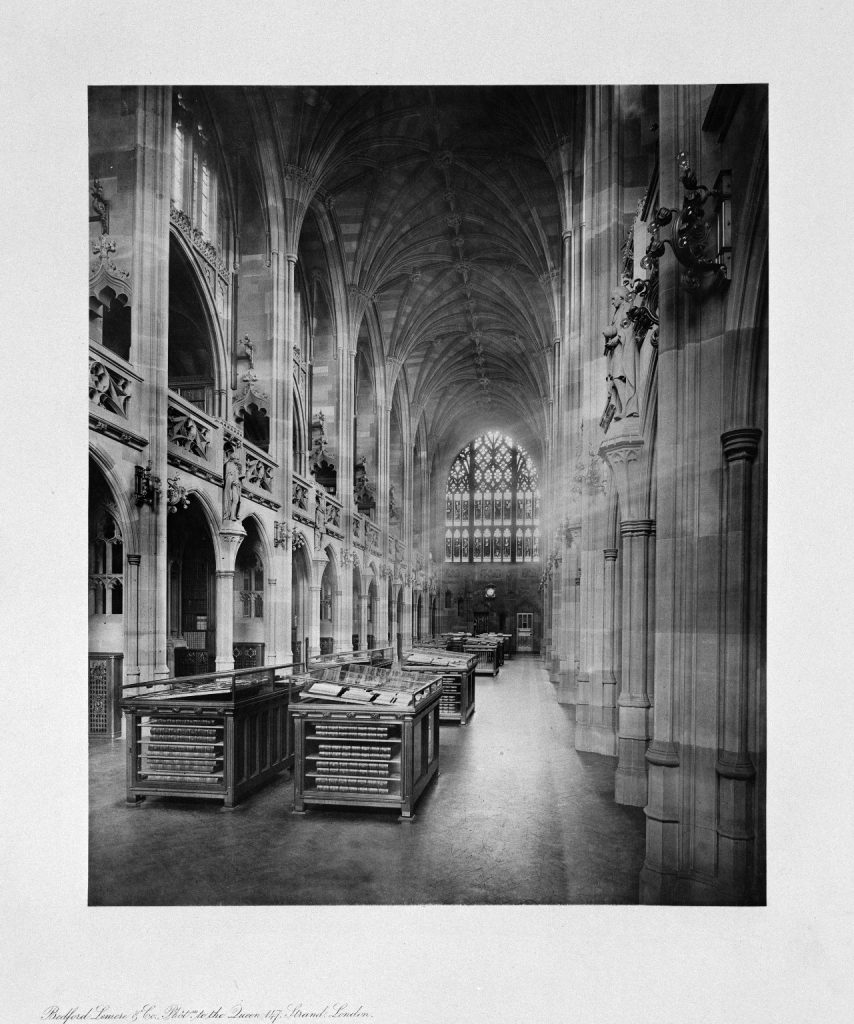

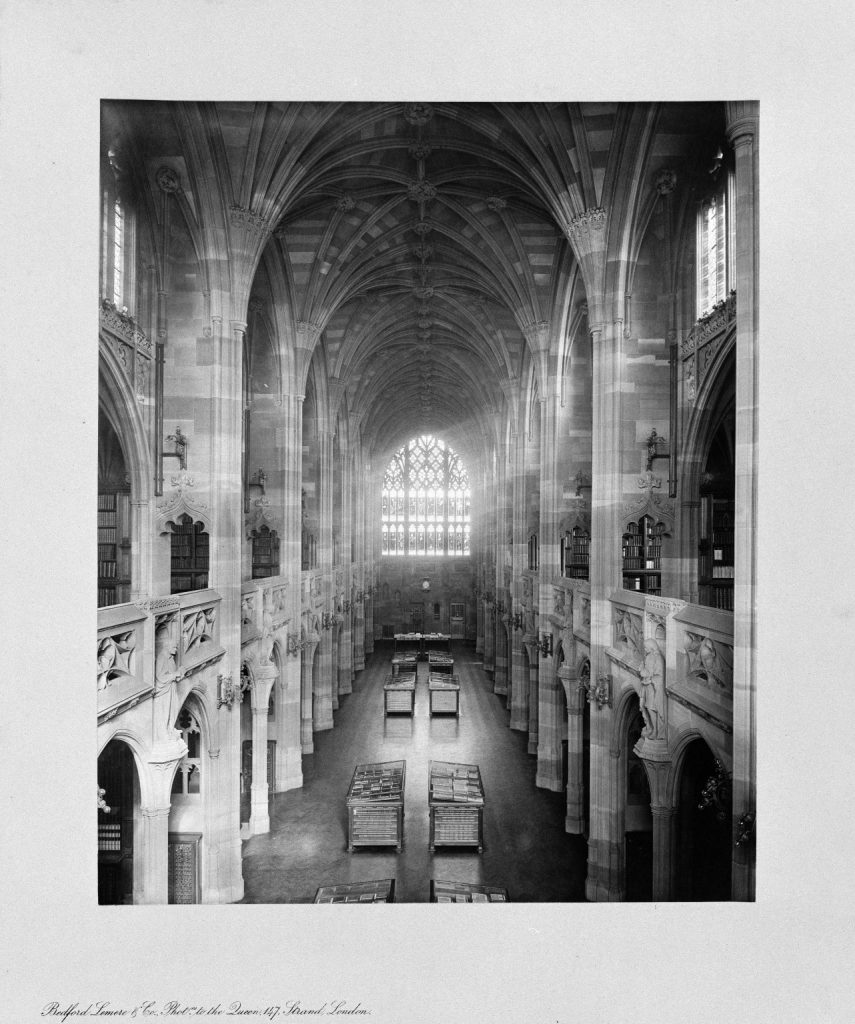

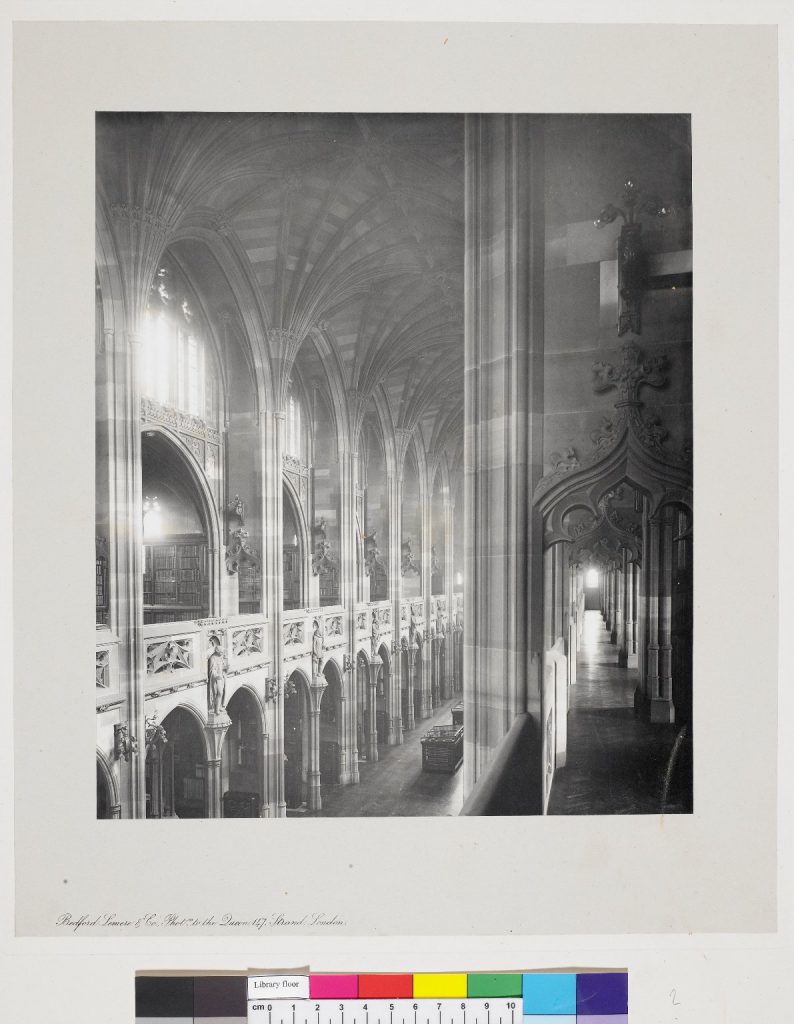

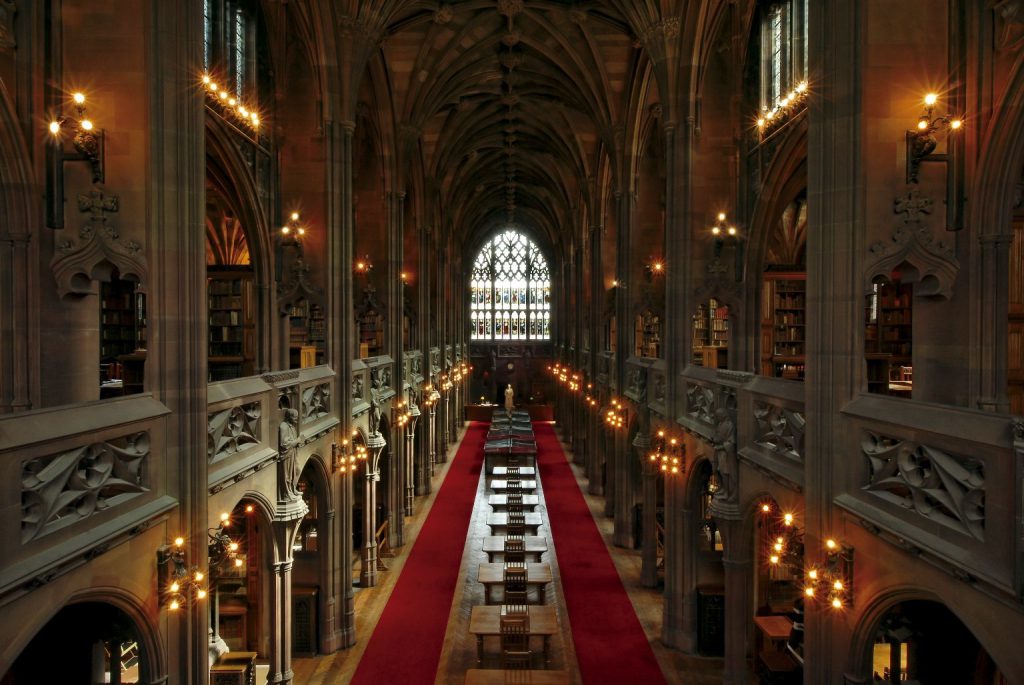

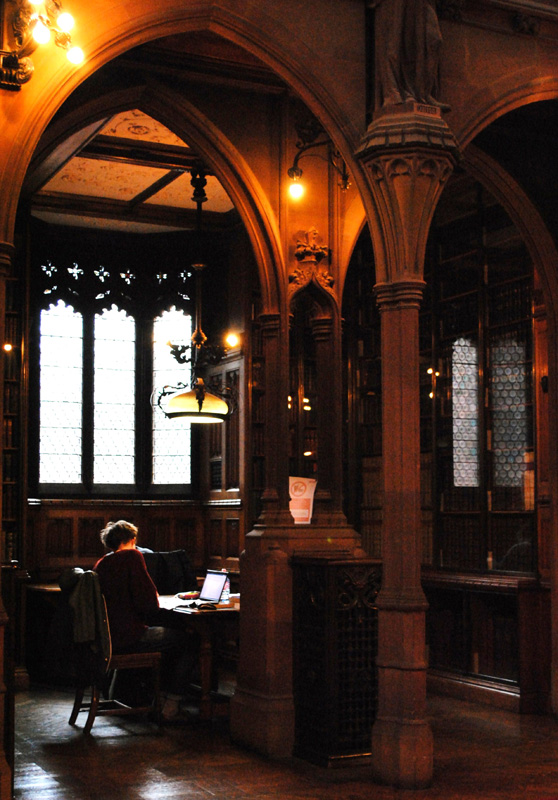

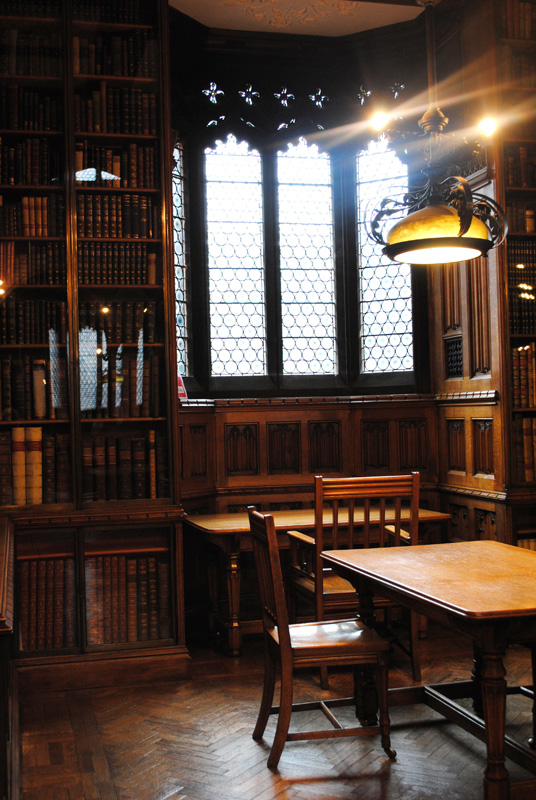

The John Rylands Library is a Victorian Gothic building on Deansgate in Manchester, England. The library, which opened to the public in 1900, was founded by Mrs Enriqueta Augustina Rylands in memory of her late husband, John Rylands. Since July 1972 the building has served as the Special Collections section of the John Rylands University Library (JRUL).

La Biblioteca John Rylands es un edificio victoriano gótico en Deansgate en Manchester, Inglaterra. La biblioteca, que se abrió al público en 1900, fue fundada por la Sra. Enriqueta Augustina Rylands en memoria de su difunto esposo, John Rylands. Desde julio de 1972, el edificio ha servido como la sección de Colecciones Especiales de la Biblioteca de la Universidad John Rylands (JRUL).

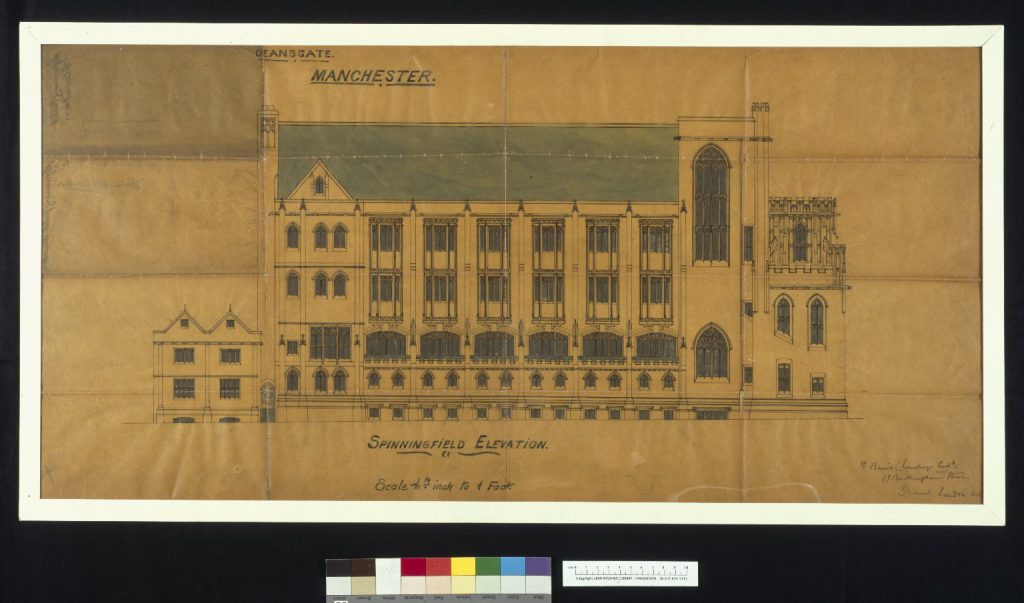

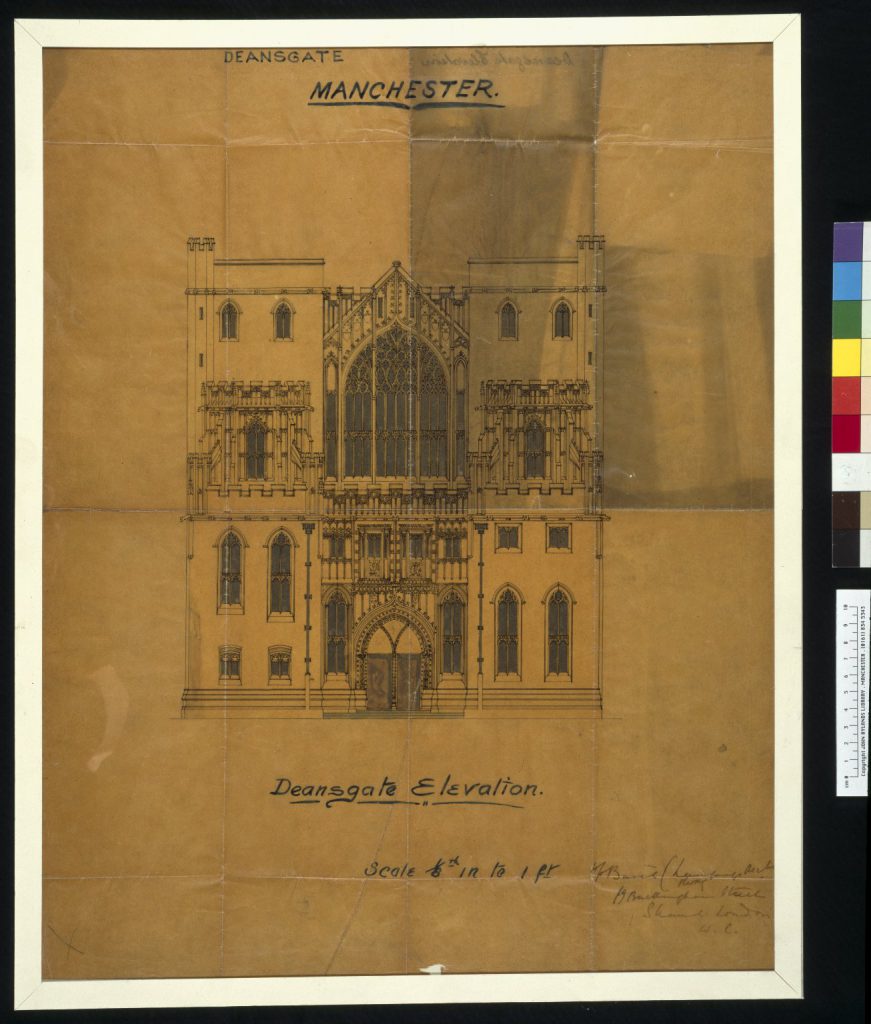

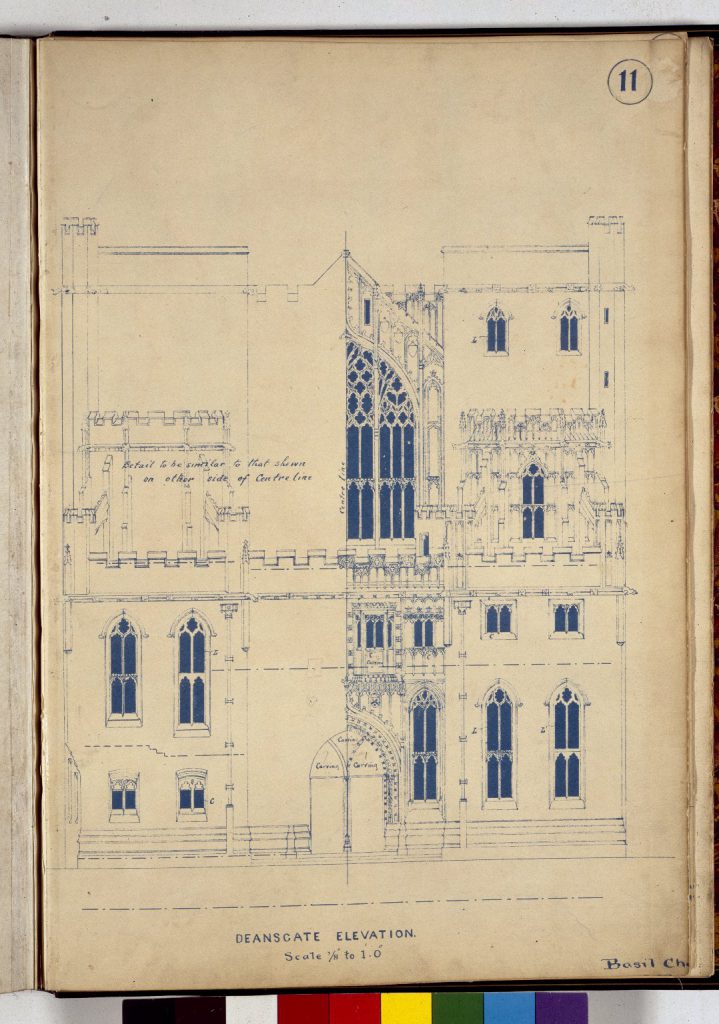

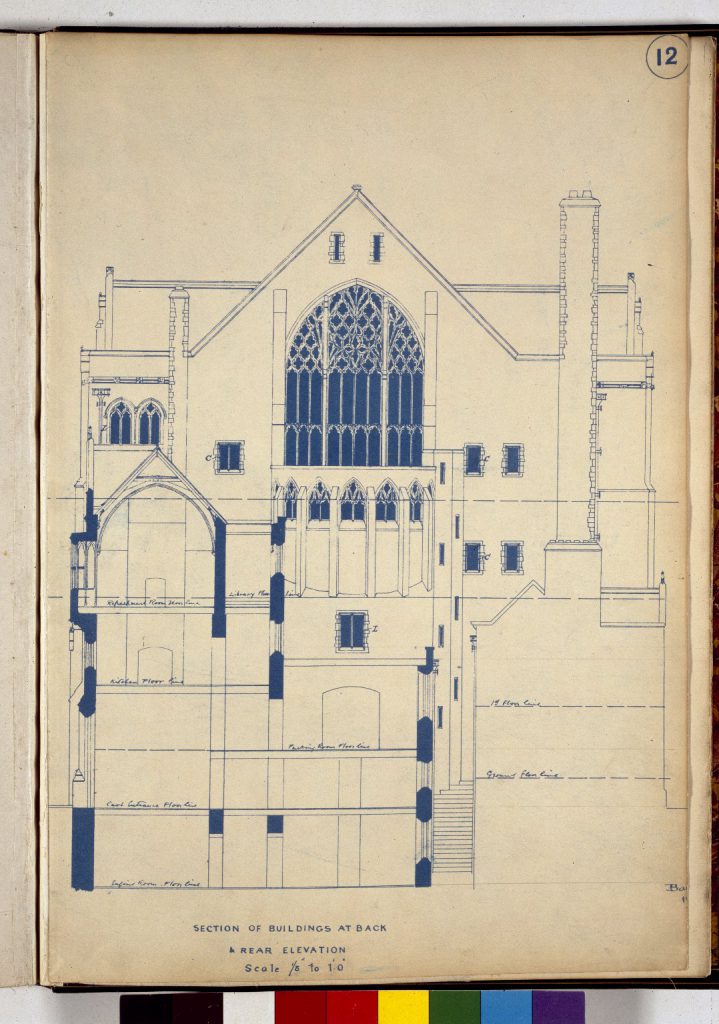

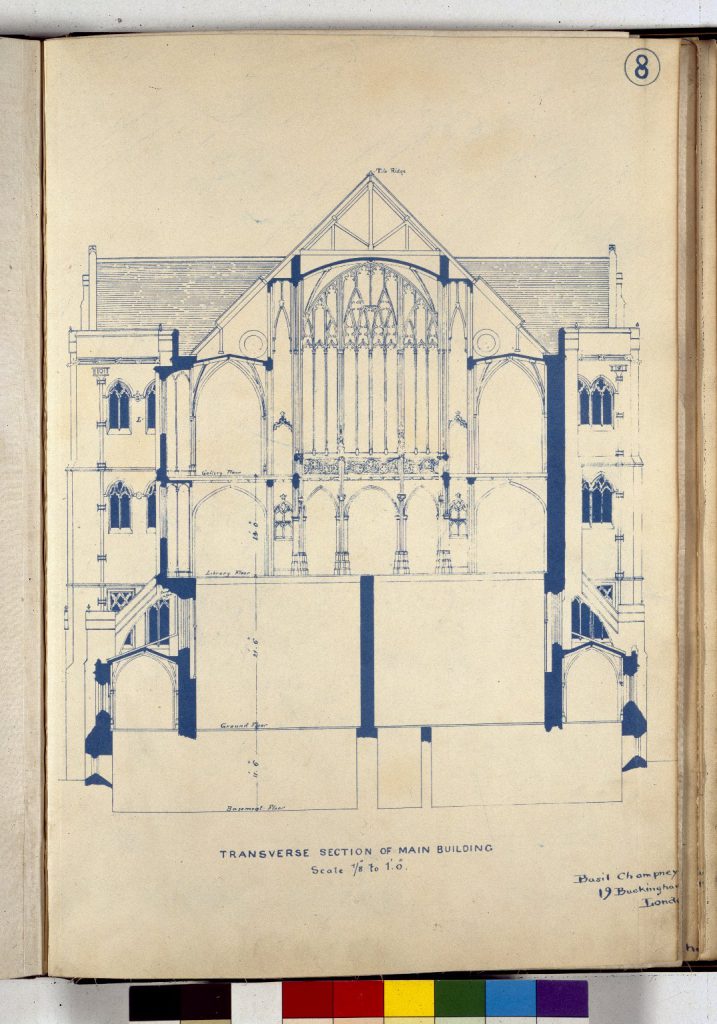

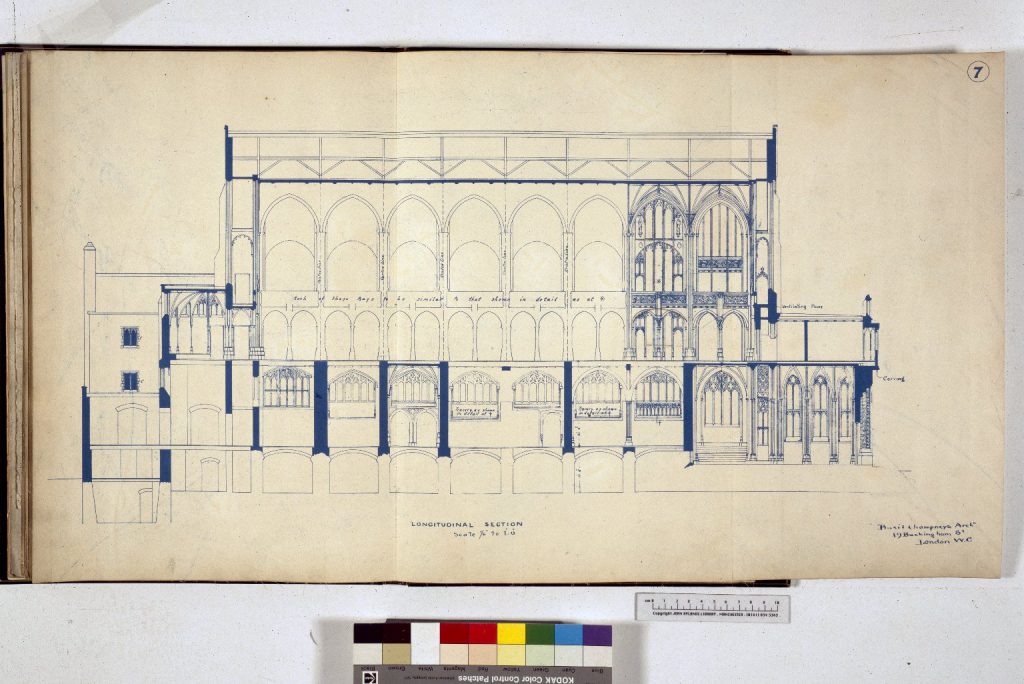

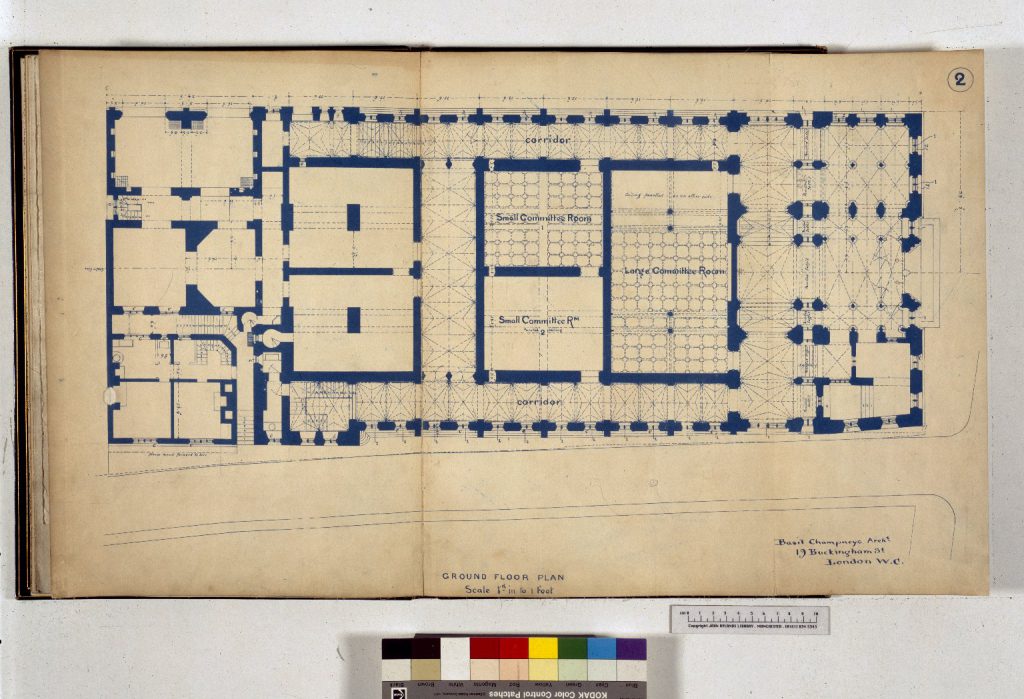

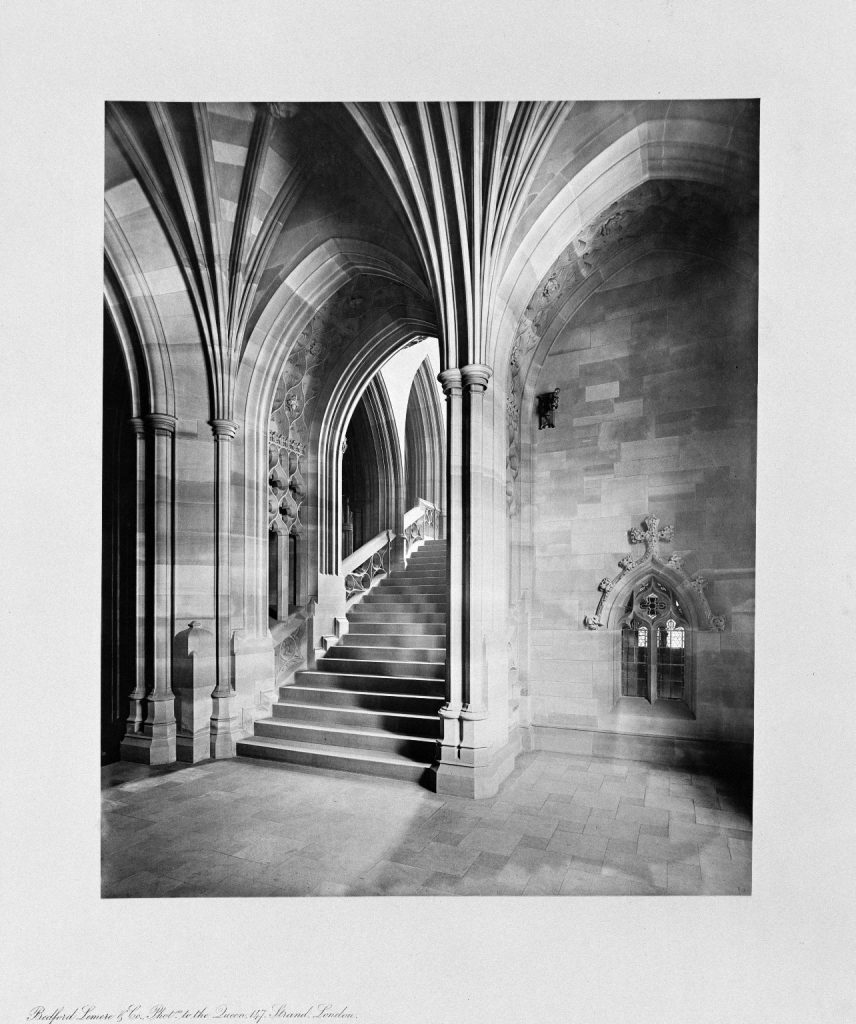

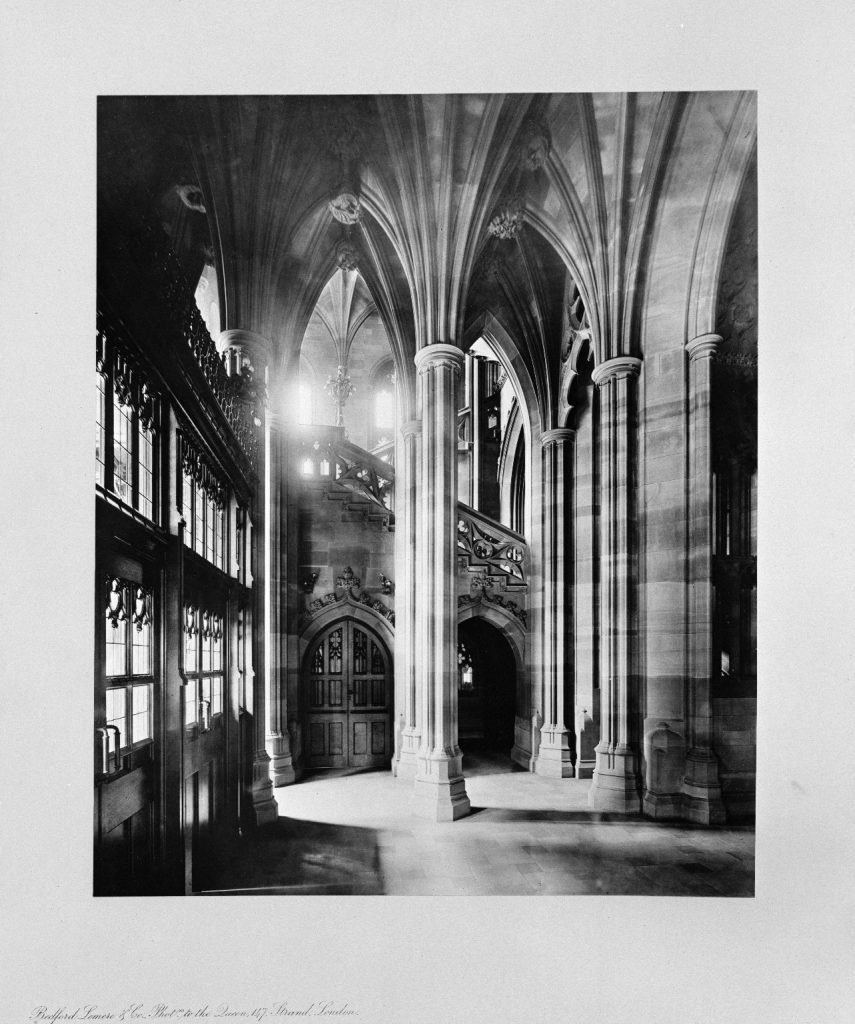

By the 19th century Manchester had become a prosperous textile manufacturing town and the demands of cotton manufacturing stimulated the growth of engineering and chemical industries. The town had become ‘abominably filthy’ and was ‘often covered, especially during the winter, with dense fogs … there is at all times a copious descent of soots and other impurities’. This, along with the overcrowded site, created many design problems for the architect. During the century most textile manufacture tended to move to newer mills in the other towns of the district while Manchester itself remained the centre of trading in cotton goods both for the home and foreign trades. Pollution from the burning of coal and gas remained a considerable nuisance even in the 1890s.The site, chosen by Mrs. Rylands to be in a central and fashionable part of the city, was awkward in shape and orientation and surrounded by tall warehouses, derelict cottages and narrow streets. The proposed position was criticised by many for its lack of surrounding space and the fact that the valuable manuscript collections were to be housed in “that dirty, uncomfortable city… not enough light to read by, and the books they already have are wretchedly kept” (written in 1901 about the Crawford MSS.) Mrs. Rylands had negotiated Deeds of Agreement with her neighbours to fix the heights of future adjacent buildings. The permissible height of the buildings on the library site was fixed at just over thirty-four feet, but it was suggested that it could be taller at the centre if there was an open area around the edges, at the height of the buildings that had been demolished to make way for the construction. Champneys incorporated this suggestion into his design, building the two towers of the main facade twelve feet back from the boundary and keeping the entrance block low, to allow light into the library. He also designed the building in a series of tiered steps with an almost flat roof to give a ‘liberal concession’ to the neighbours’ ‘right to light’. When the library was opened, the main reading room on the first floor, thirty feet above the ground and twelve feet from all four boundaries, was noted for the pleasant contrast between the ‘sullen roar’ of Manchester and the ‘internal cloister quietude of Rylands’. It was lit by oriel windows in the reading alcoves supplemented by high clerestory windows along both sides.

En el siglo XIX, Manchester se había convertido en una próspera ciudad de fabricación de textiles y las demandas de la fabricación de algodón estimularon el crecimiento de las industrias de ingeniería y química. La ciudad se había vuelto “abominablemente sucia” y estaba “cubierta a menudo, especialmente durante el invierno, con densas neblinas … en todo momento hay un copioso descenso de hollín y otras impurezas”. Esto, junto con el sitio superpoblado, creó muchos problemas de diseño para el arquitecto. Durante el siglo, la mayor parte de la manufactura textil tendió a trasladarse a las fábricas más nuevas en las otras ciudades del distrito, mientras que el mismo Manchester siguió siendo el centro del comercio de productos de algodón para el hogar y el comercio exterior. La contaminación por la quema de carbón y gas siguió siendo una molestia considerable incluso en la década de 1890. El sitio, elegido por la Sra. Rylands para estar en una parte central y de moda de la ciudad, tenía una forma y una orientación incómodas y estaba rodeado de altos almacenes, abandonado. Casas rurales y calles estrechas. La posición propuesta fue criticada por muchos por su falta de espacio circundante y por el hecho de que las valiosas colecciones de manuscritos se alojarían en “esa ciudad sucia e incómoda … no hay suficiente luz para leer, y los libros que ya tienen están mal guardados” (escrito en 1901 sobre Crawford MSS). La Sra. Rylands había negociado Escrituras de acuerdo con sus vecinos para arreglar las alturas de los futuros edificios adyacentes. La altura permisible de los edificios en el sitio de la biblioteca se fijó en poco más de treinta y cuatro pies, pero se sugirió que podría ser más alto en el centro si hubiera un área abierta alrededor de los bordes, a la altura de los edificios que tenían Demolido para dar paso a la construcción. Champneys incorporó esta sugerencia en su diseño, construyendo las dos torres de la fachada principal a doce pies del límite y manteniendo el bloque de entrada bajo, para permitir la entrada de luz a la biblioteca. También diseñó el edificio escalonado con un techo casi plano para otorgar una “concesión liberal” al “derecho a la luz” de los vecinos. Cuando se abrió la biblioteca, la sala de lectura principal en el primer piso, a treinta pies sobre el suelo y a doce pies de los cuatro límites, se destacó por el agradable contraste entre el ‘rugido’ de Manchester y el ‘claustro interno en paz de de Rylands ‘. Estaba iluminado por ventanas de mirador en los nichos de lectura complementados por ventanas de alto nivel a lo largo de ambos lados.

The building was constructed of Cumbrian sandstone, the interior a delicately-shaded ‘Shawk’ stone (from Dalston, varying between sand and a range of pinks) and the exterior, dark red Barbary stone from Penrith, built around an internal steel framed structure and brick arched flooring. The red ‘Barbary plain’ sandstone, which Champneys believed ‘had every chance of proving durable’ for the exterior, was an unusual choice in late Victorian Manchester. It did, however, prove relatively successful, as an inspection by Champneys in 1900 revealed little softening by the ‘effects of an atmosphere somewhat charged with chemicals’ although, by 1909 some repairs were needed.

El edificio se construyó con piedra arenisca de Cumbria, el interior era una piedra ‘Shawk’ (de Dalston, que varía entre la arena y una variedad de rosas) y la piedra de Berbería roja oscura de Penrith, construida alrededor de una estructura interna de acero. Suelos de ladrillo arqueado. La arenisca roja “Barbary plain”, que Champneys creía “tenía todas las posibilidades de ser duradera” para el exterior, era una elección inusual en el último Victorian Manchester. Sin embargo, resultó ser relativamente exitoso, ya que una inspección realizada por Champneys en 1900 reveló que los “efectos de una atmósfera algo cargada de químicos” se suavizaron, aunque para 1909 se necesitaban algunas reparaciones.

Champneys also suggested to Mrs. Rylands that, in order to protect the valuable books and manuscripts, ‘it will be very desirable to keep the air in the interior of the building as clear and free from smoke and chemical matter (both of which are held in the air of Manchester) as may be possible’. The ground floor had been built with numerous air inlets and, although his client felt that it would prove impossible to exclude foul air, Champneys installed jute or hessian screens to trap the soot, with water sprays to catch the sulphur and other chemicals, which was a very advanced system for the period. Internal screen doors were employed in the entrance hall to prevent the air being ‘fouled by the opening of the outer doors’ with internal swing doors between the circulation areas and the main library to ‘preserve the valuable books from injury. By 1900 the ventilation system had evolved to include electric fans to draw in air at pavement level through coke screens sprayed with water.

Champneys también le sugirió a la Sra. Rylands que, para proteger los valiosos libros y manuscritos, “será muy deseable mantener el aire en el interior del edificio tan claro y libre de humo y materia química (ambos se sostienen). en el aire de Manchester) como sea posible “. La planta baja se había construido con numerosas entradas de aire y, aunque su cliente sentía que sería imposible excluir el aire contaminado, Champneys instaló pantallas de yute o hessian para atrapar el hollín, con rociadores de agua para atrapar el azufre y otros productos químicos, que eran Un sistema muy avanzado para el periodo. Las puertas con mosquitero interno se emplearon en el hall de entrada para evitar que el aire se ensucie con la apertura de las puertas exteriores con puertas batientes internas entre las áreas de circulación y la biblioteca principal para preservar los valiosos libros. Para 1900, el sistema de ventilación había evolucionado para incluir ventiladores eléctricos para aspirar aire al nivel del pavimento a través de pantallas de coque rociadas con agua.

|

| Image by izzy verena |

|

| Image by izzy verena |

|

| Image by izzy verena |

Via: