This article is part of the Listening Rooms series, a personal project curated by Biljana Janjusevic that propose mapping of the crucial interior design movements, in order to reinterpret their role to the architecture as a discipline and their importance in contemporary (and past) everyday life.

Este artículo es parte de la serie Listening Rooms , comisariada por Biljana Janjusevic que propone un mapeo de los movimientos cruciales en el diseño de interiores, con el fin de reinterpretar su papel en la arquitectura como disciplina y su importancia en la vida cotidiana contemporánea (y pasada).

***

Architecture’s roll in public life has evolved with pace of development of our societies. Seldom has any form of institution developed without parallelly giving rise to a architectural articulation of its power. But societies change and the historical memory is of short breath. This is the reason why certain buildings seem extremely surprising to a contemporary observer. One of such buildings is Public Children Home in Stockholm.

El papel de la arquitectura en la vida pública ha evolucionado al ritmo del desarrollo de nuestras sociedades. Rara vez se ha desarrollado alguna forma de institución sin que haya surgido paralelamente una articulación arquitectónica de su poder. Pero las sociedades cambian y la memoria histórica es de corto aliento. Esta es la razón por la que ciertos edificios parecen extremadamente sorprendentes para un observador contemporáneo. Uno de esos edificios es el Hogar Infantil Público de Estocolmo.

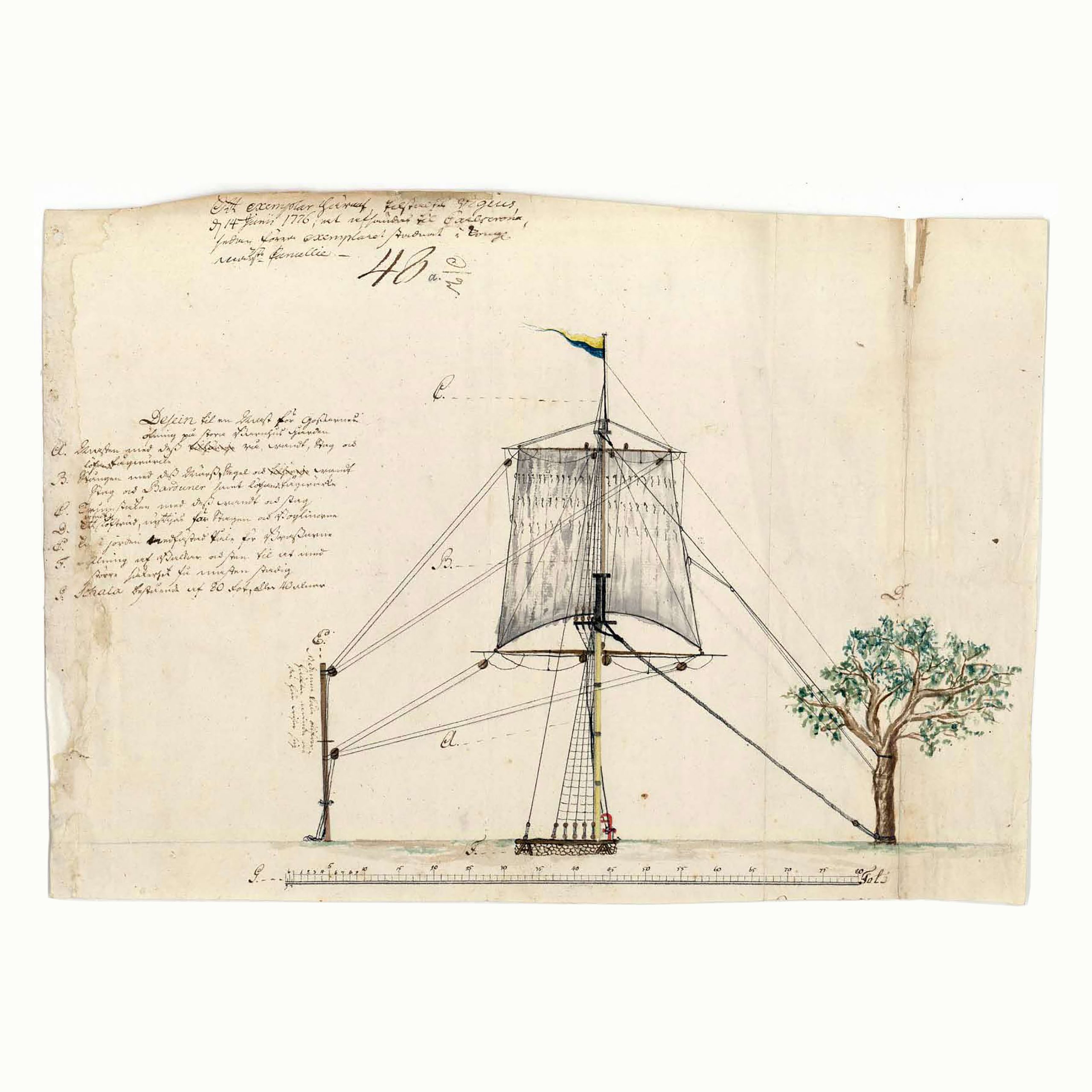

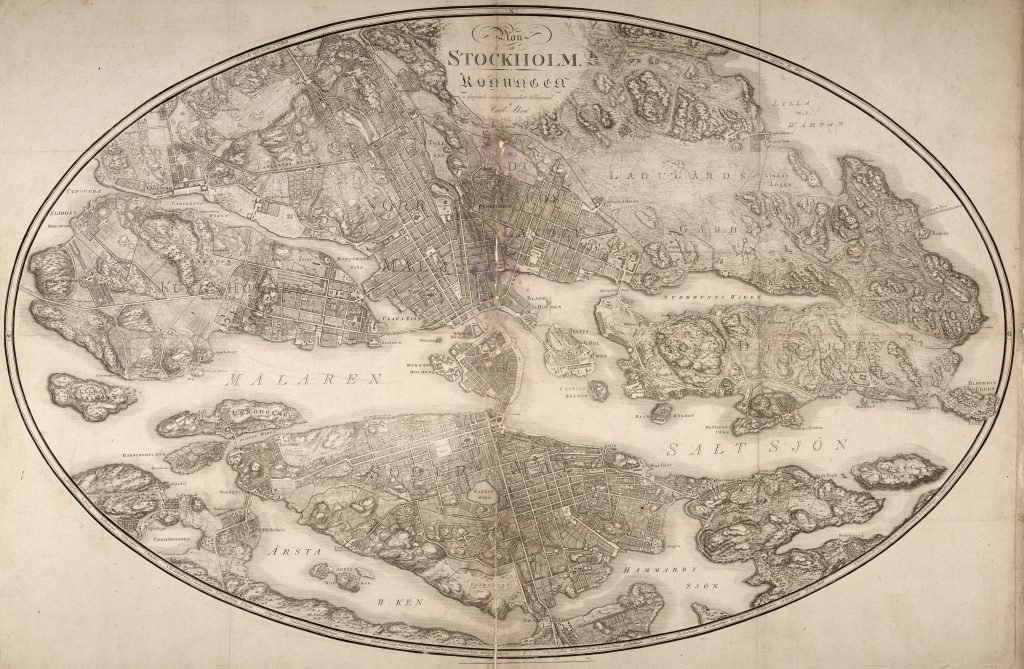

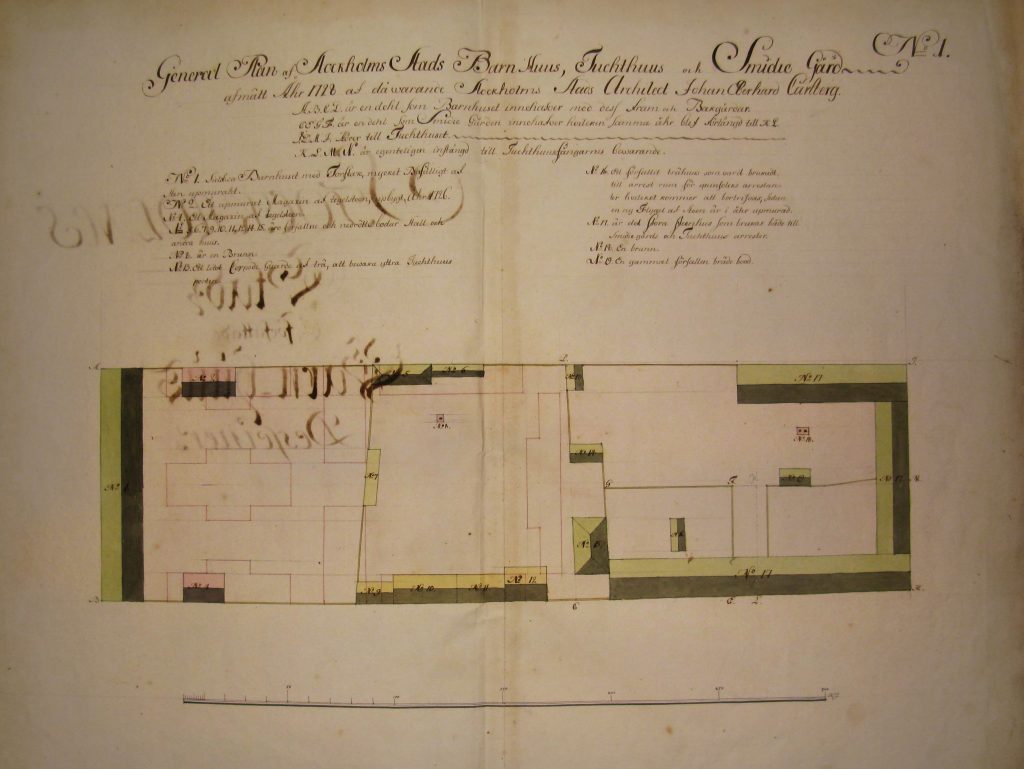

The year was 1633, when the master teacher Matthias got a permission for opening a first public children home at then peripheral Drottninggatan street in Stockholm. The building and surrounding facilities were completed 5 years later – 1638. The complex was designed by an unknown architect, but later documented and expanded by the city architect of Stockholm Johan Eberhard Carlberg in the period between 1729 – 1748. At the time, the building was officially a collective orphanage for all the homeless children, which were incredibly numerous. However, since these kids were regarded as lowest class citizens due to their undesirable behaviour (begging, stealing etc) and lack of education, it served as a prison and their training facility as well.

Era el año 1633, cuando el maestro Matthias obtuvo un permiso para abrir un primer hogar infantil público en la entonces periférica calle Drottninggatan de Estocolmo. El edificio y las instalaciones circundantes se terminaron 5 años después, en 1638. El complejo fue diseñado por un arquitecto desconocido, pero posteriormente fue documentado y ampliado por el arquitecto municipal de Estocolmo Johan Eberhard Carlberg en el periodo comprendido entre 1729 y 1748. En aquella época, el edificio era oficialmente un orfanato colectivo para todos los niños sin hogar, que eran increíblemente numerosos. Sin embargo, como estos niños eran considerados ciudadanos de clase baja debido a su comportamiento indeseable (mendicidad, robos, etc.) y a su falta de educación, servía también de prisión y de centro de formación.

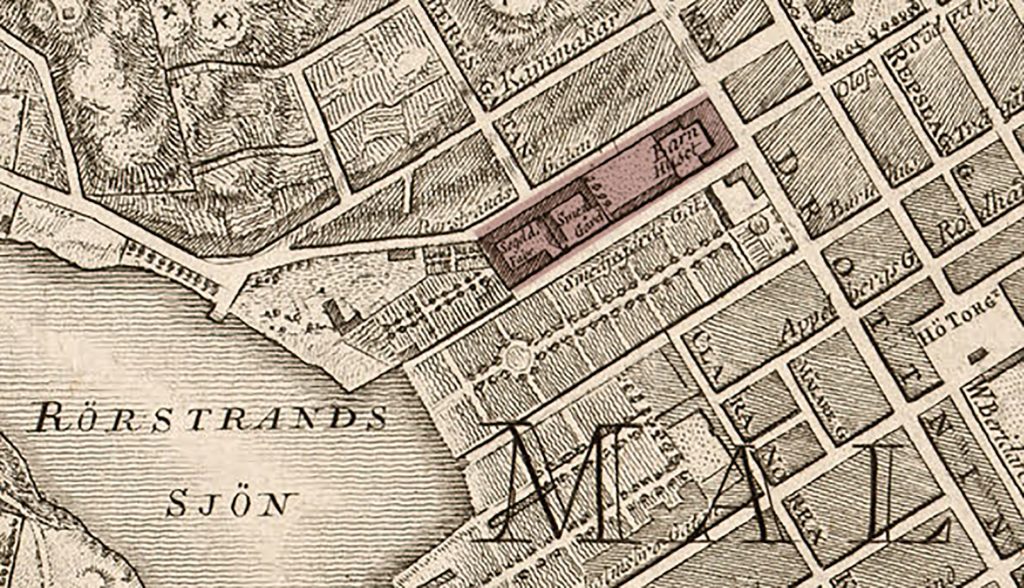

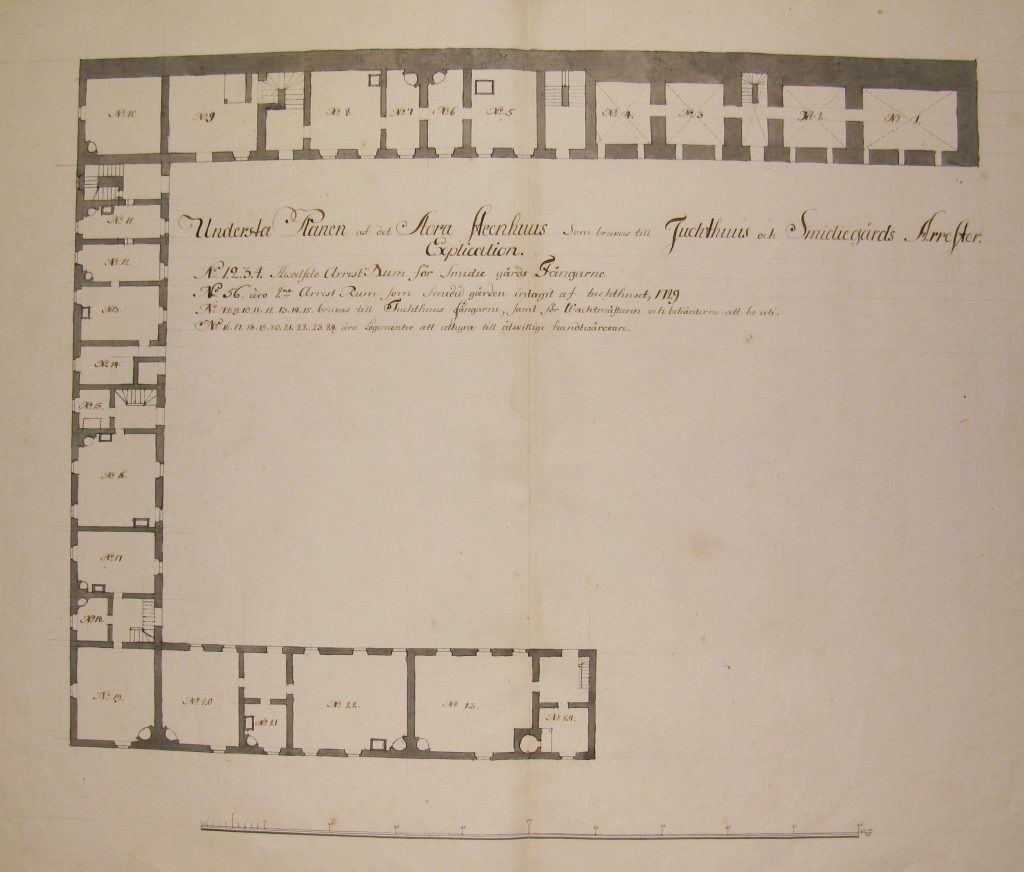

The facility of the Public Children Home (Allmänna Barnhuset) was enclosed by a tall fence, surrounding a generous courtyard, equipped with a collective Orphanage house, a smithy, a so called “house of correction” – Tukthus, several workshops and a water well. Complex is divided in two volumes. The smithy and “the correction house” were making up one urban agglomeration, while the Children House was a separate building. The former included a particularly secured prison hall and up until 1772 even a torture room. The ground floor of this block was basically consisting of cells for Tukthus and smithies prisoners and a small chapel, which the reason why the walls are particularly thick and the window openings narrow and scarce. Building itself is a very thin, L shaped volume with communication on side, directly from the street. Outside in the courtyard, another small facility housed a brewery and a small public bath.

Las instalaciones del Hogar Público de Niños (Allmänna Barnhuset) estaban cerradas por una alta valla, que rodeaba un generoso patio, equipado con una casa colectiva del Orfanato, una herrería, una llamada “casa de corrección” – Tukthus, varios talleres y un pozo de agua. El complejo está dividido en dos volúmenes. La herrería y la “casa de corrección” formaban una aglomeración urbana, mientras que la Casa de los Niños era un edificio independiente. La primera incluía una sala de prisión especialmente segura y hasta 1772 incluso una sala de tortura. La planta baja de este bloque consistía básicamente en celdas para los presos y una pequeña capilla, por lo que los muros son especialmente gruesos y los huecos de las ventanas estrechos y escasos. El edificio en sí es un volumen muy delgado, en forma de L, con comunicación lateral, directamente desde la calle. Fuera, en el patio, otra pequeña instalación albergaba una cervecería y un pequeño baño.

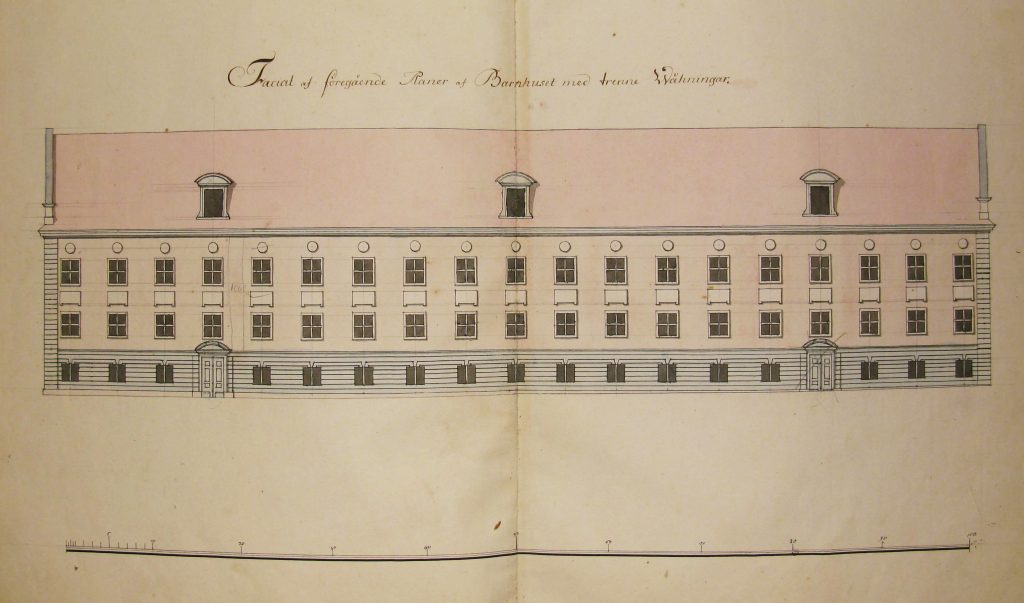

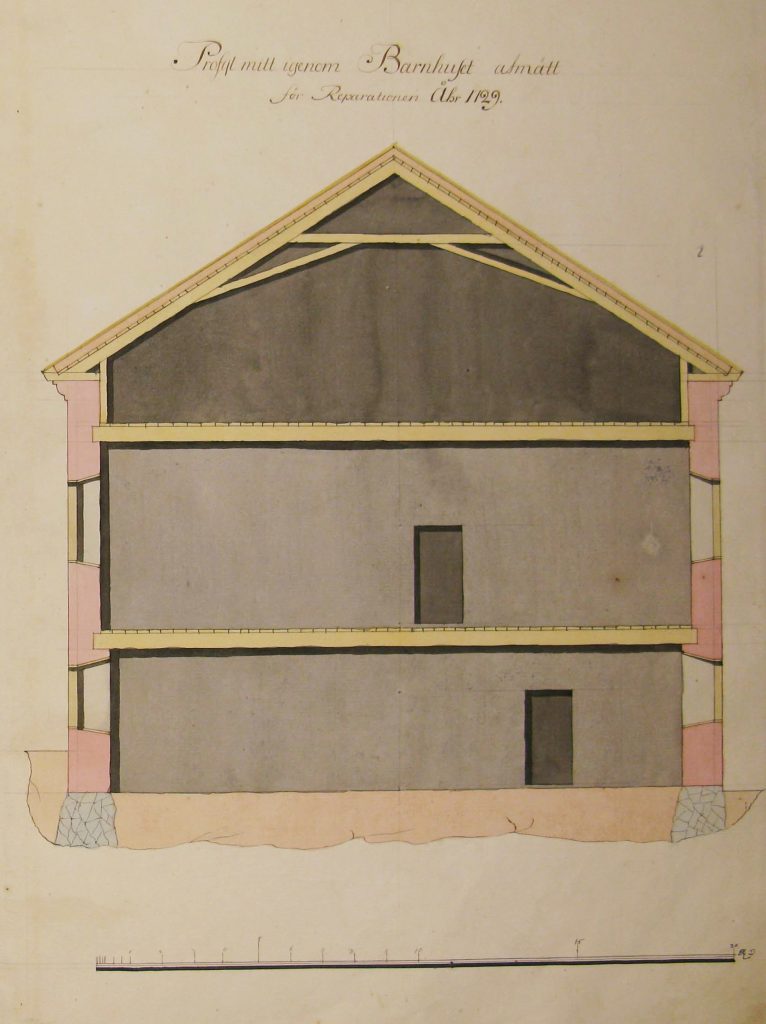

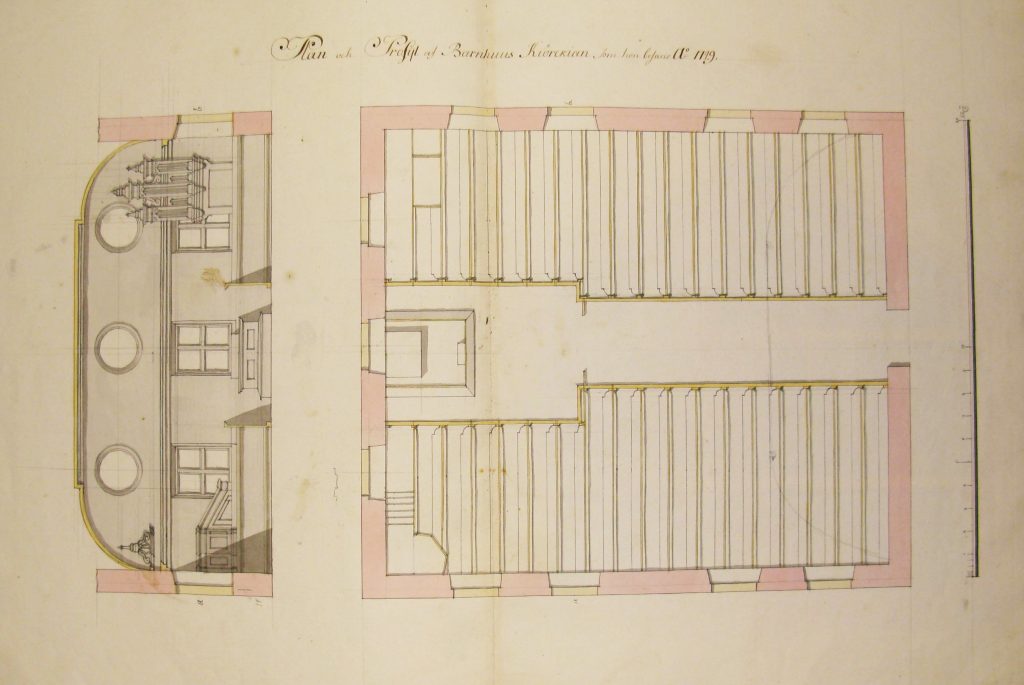

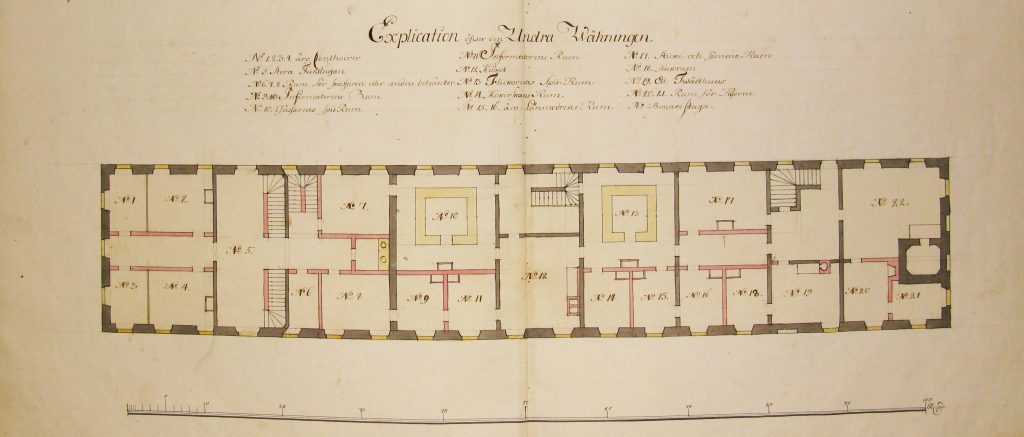

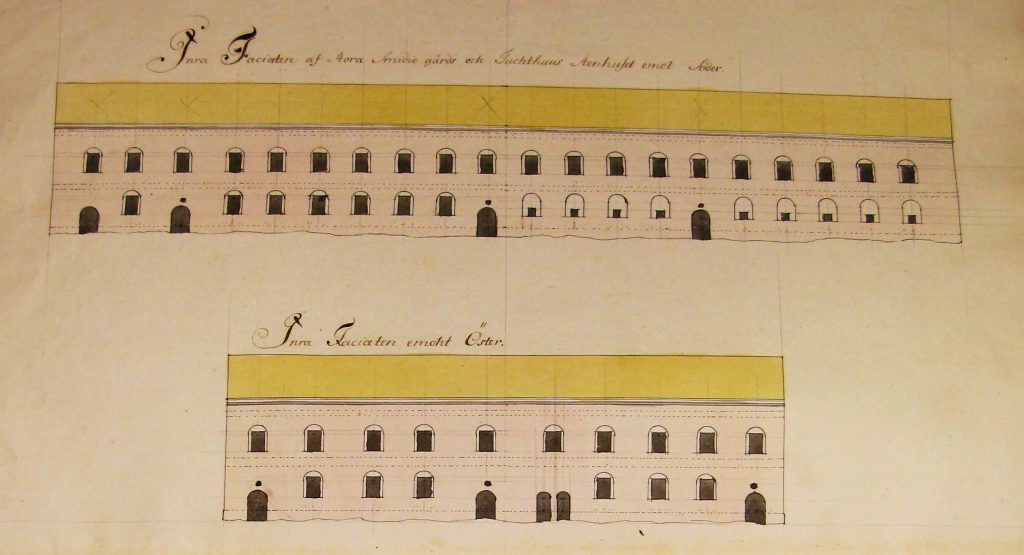

In the orphanage House we see a contrasting plan solution. The three storey building was in essence a long lamella type, with several staircases, very frequent chimneys, larger and more frequent windows, with a variety of common rooms. Façade drawings of various proposals of expansion by J. E. Carlberg also depict a proportional rationality with emphasized floor plan and two unified floors above, with occasional roof ridges in the attic. Orphanage House included a church, classrooms and a small library. The boys and girls sleeping and dining chambers were separated in two wings. The big kitchen was situated in the middle of the house, directly connected the main stairs. According to the common practice of the time, the main stone structure was supported by some wooden elements and the whole building always received a plaster coating. Courtyard is the public heart of the space, as it was used for teaching, gathering and physical exercise.

En la Casa del Orfanato vemos una solución de planta contrastada. El edificio de tres plantas era en esencia un tipo alargado de crujía estrecha, con varias escaleras, chimeneas muy frecuentes, ventanas más grandes y abundantes, con una variedad de salas comunes. Los dibujos de fachada de varias propuestas de ampliación de J. E. Carlberg también muestran una racionalidad proporcional con planta acentuada y dos pisos unificados por encima, con crestas ocasionales en el ático. La Casa del Orfanato incluía una iglesia, aulas y una pequeña biblioteca. Los dormitorios y comedores de niños y niñas estaban separados en dos alas. La gran cocina estaba situada en el centro de la casa, conectada directamente con la escalera principal. Según la práctica habitual de la época, la estructura principal de piedra se completaba con algunos elementos de madera y todo el edificio recibía siempre un revestimiento de yeso. El patio es el corazón público del espacio, ya que se utilizaba para la enseñanza, la reunión y el ejercicio físico.

In practice, the limitation of freedom and rigorous punishments of children trying to desert the facility was seen as a part of their training process. All taken kids were namely trained to be useful workforce. At the age of 8, they were “borrowed” to craftsmen’s workshops to earn their own living. The boys were mainly trained to be helping in the sailing fleet, while girls would typically end up being household keepers or in the sewing factories. In 18th century, parallel to the change of the social norms, the children were not trained for work anymore but mainly prepared be adopted by foster families.

En la práctica, la limitación de la libertad y los rigurosos castigos a los niños que intentaban desertar del centro se consideraban parte de su proceso de formación. Todos los niños acogidos fueron entrenados concretamente para ser mano de obra útil. A la edad de 8 años, eran “prestados” a talleres artesanales para ganarse la vida. A los niños se les formaba principalmente para ayudar en la flota de vela, mientras que las niñas solían acabar siendo empleadas del hogar o en las fábricas de costura. En el siglo XVIII, paralelamente al cambio de las normas sociales, los niños ya no se formaban para trabajar, sino que se preparaban principalmente para ser adoptados por familias de acogida.

Around 70 000 children were inhabiting the complex, during two and a half centuries of its existence. Up to recent times (1917), parents who would abandon their unwanted children exercised the right to be anonymous. In 1886 the old Children home was demolished and the Orphanage moved.

Alrededor de 70.000 niños habitaron el complejo durante dos siglos y medio de su existencia. Hasta tiempos recientes (1917), los padres que abandonaban a sus hijos no deseados ejercían el derecho al anonimato. En 1886 se demolió el antiguo Hogar de Niños y se trasladó el Orfanato.

Fascination of the Barnhus is mainly derived from its historical context. A story of an orphanage prison that once was, reminds us how sharply has our worldview changed and progressed in last couple of centuries. It also suggests variability of scenarios and functions happening behind the city facades. After all, the buildings are made to be lived in and their function adapted to the demands of times.

La fascinación por el Barnhus se deriva principalmente de su contexto histórico. La historia de un orfanato-prisión que fue un día, nos recuerda lo mucho que ha cambiado y progresado nuestra visión del mundo en los últimos dos siglos. También sugiere la variabilidad de escenarios y funciones que se dan detrás de las fachadas de la ciudad. Al fin y al cabo, los edificios están hechos para ser habitados y su función se adapta a las exigencias de los tiempos.

This example also underlines the importance of treating architectural drawings as precious documents of common heritage. The power of the drawing is priceless, especially when a time transcending translation of the social order and the feeling of place is to be presented to future generations.

Este ejemplo también subraya la importancia de tratar los dibujos arquitectónicos como preciosos documentos del patrimonio común. El poder del dibujo no tiene precio, sobre todo cuando se quiere presentar a las generaciones futuras una traducción del orden social y del sentimiento del lugar que trasciende el tiempo.

All drawings except for the cover drawing:

Architekt :Carlberg, Johan Eberhard (1683-1773)

Date:

1729 – 1748

Source:

Stockholms stadsarkiv

Stockholms stadsarkiv/NS30/Allmänna barnhusets kartor och ritningar/AI:31-47 https://stockholmskallan.stockholm.se/teman/stockholms-sociala-historia/barnhem/

***

Biljana Janjusevic is an architect, master graduate from Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden(2019) with a background of architectural education at University of Montenegro(2015). Parallel to professional engagement in architecture, I cherish genuine interests in wider social implications of design and its correlation to the society and cultural heritage. My attitude towards built environment reflects a consistent personal aim to act sustainably and promote sustainable thinking in architectural praxis, by merging ever evolving artistic values, philosophical learning and professional experiences. I am working as interior architect at the moment, but my experiences include building design, lighting and product design as well.