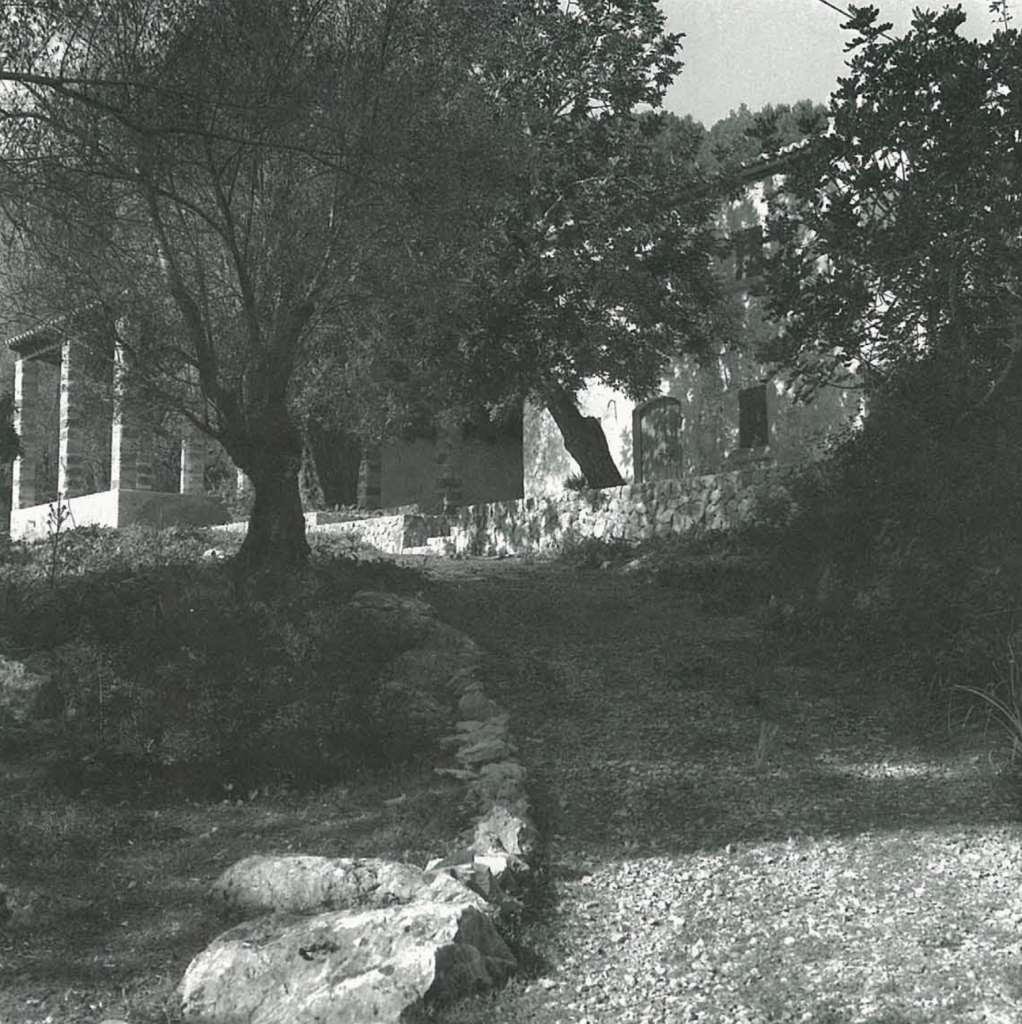

We had reached the first turning to enter Pollensa , we turn left leaving behind the hermitage of Roser-Vell and took the only road that goes into the small valley of Colonya . Turn right onto a steep path just beyond the turn-off that leads to the house of the “senyor” of Colonya. Between masonry walls covered with brambles, among almond trees, carob trees and the odd olive tree, we headed down a dirt track closed at the end by a gate, flanked by two masonry walls. At this gate the mountain began. We had reached the land of “Ses Rotes”.

Habíamos llegado a la primera desviación para entrar en Pollensa , giramos a la izquierda dejando atrás la ermita del Roser-Vell y tomamos el único camino que se adentra en el pequeño valle de Colonya . Giramos a la derecha por un empinado camino que hay un poco más allá de la desviación que lleva a la casa del “senyor” de Colonya. Entre muretes de mamposteria recubiertos de zarzas, entre almendros, algarrobos y algún olivo enfilamos un camino de tierra cerrado en su final por una puerta; puerta flanqueada por dos muros de mampostería. En esta puerta comenzaba el monte. Habíamos llegado al terreno de “Ses Rotes”.

A few years ago, almost hidden among the trees and undergrowth, there was a tiny house made of sandstone, about twenty-five square metres per floor, which had been abandoned for many years. When we knew it , it had been inhabited by some “hippies” who had reconstructed the window openings with car windows and plaster paste: the water they used was rainwater from a small cistern without installation and the toilet was a hole in the ground with some boards as a seat, next to the house. They left and others came and kept it until it was abandoned again, serving as a corral for the sheep and storage for the carob harvest. One day the “senyor” of Colonya bought “Ses Rotes”: it was his landscape, a landscape of rocks and centenary olive trees on a south-facing slope formerly filled with stone walls.

Hace unos años, casi oculta entre los árboles y la maleza, existía una minúscula casa de marés de unos veinticinco metros cuadrados por planta durante muchos años abandonada. Cuando la conocimos había sido habitada por unos “hippies” que habían reconstruido con cristales de coches y pasta de yeso los huecos de las ventanas: el agua que utilizaban era la de la lluvia de un pequeño aljibe sin instalación y el inodoro era un agujero en el suelo con unas tablas como asiento, próximo a la casa. Estos se marcharon y vinieron otros que la mantuvieron hasta que de nuevo, fue abandonada sirviendo de corral a las ovejas y de almacenamiento de la cosecha de algarrobas. Un día el “senyor” de Colonya compró “Ses Rotes”: era su paisaje, un paisaje de rocas y olivos centenarios sobre una ladera orientada al Sur antiguamente terraplenada de muros de piedra.

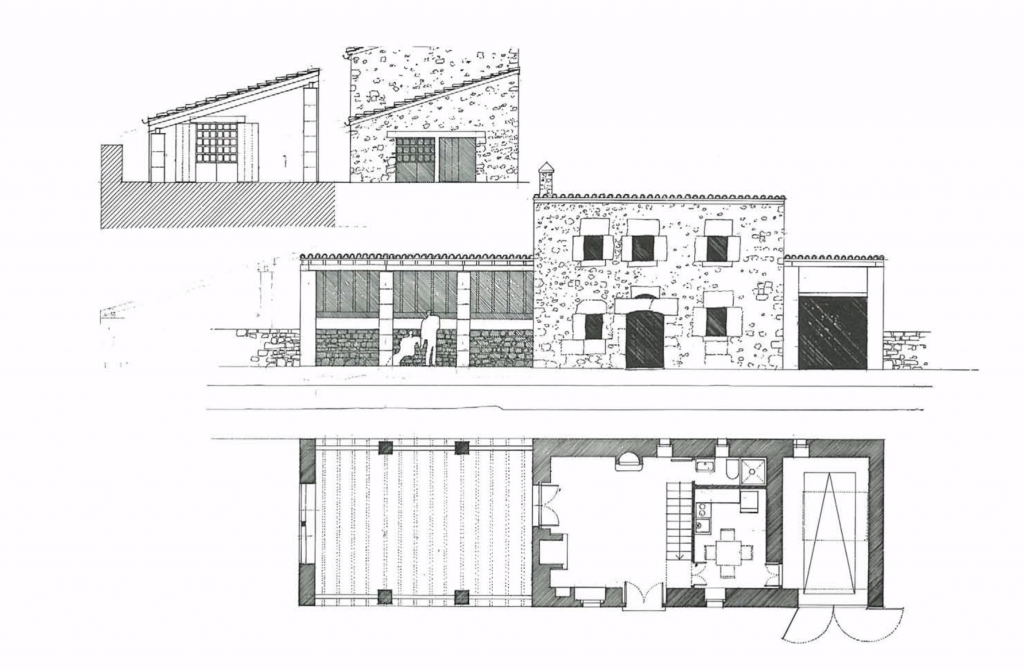

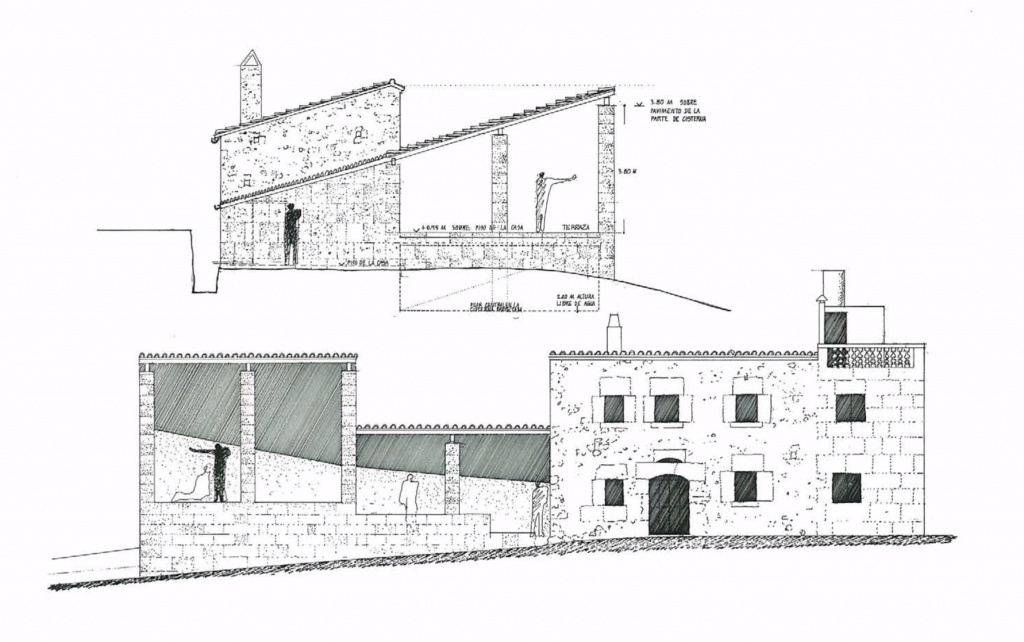

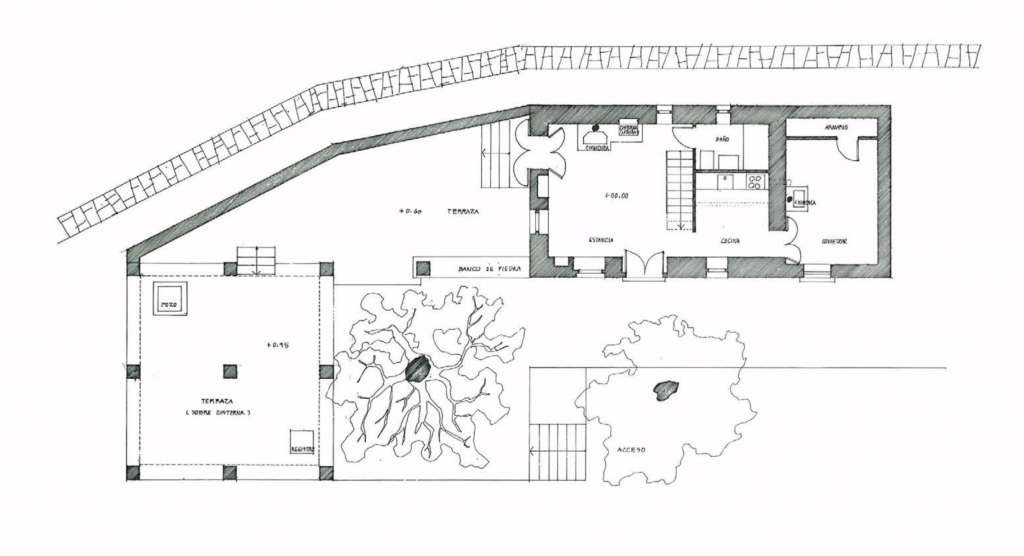

But let’s recover the thread of our brief history of the arrival. We had entered “Ses Rotes”. Watching over the gate, on the hillside and now partially visible among the trees, remains that tiny house reabsorbed in an architectural landscape of new grandeur. The incorporation of new built elements has substantially modified the surroundings, creating a new reference point for the apparently anarchic growth of vegetation. But let’s go up the hillside and reach the stone platform that extends as ground zero of the staging. The scale of the site has changed; to the north a low, enclosed wall with a small passageway, and to the south, pillars of old sandstone support a large tiled roof and define the limit of what has been built. Overhanging this platform and framing with the pillars and the cornice a centenary olive tree, the square porch of 9 pillars stands out: below it, the large cistern, a fundamental element for life in a Mallorcan house in the countryside. The obligatory response to an elementary and immediate need to increase the storage capacity for rainwater has been the suggestion and stimulus for the expansion and new expression of the house.

Pero recuperemos el hilo de nuestra breve historia de la llegada. Habíamos entrado en “Ses Rotes”. Vigilante de la puerta, sobre la ladera y ahora parcialmente visible entre los árboles, permanece esa minúscula casa reabsorbida en un paisaje arquitectónico de nueva grandeza. La incorporación de nuevos elementos construidos ha modificado sustancialmente el entorno creando una nueva referencia del crecimiento aparentemente anárquico de la vegetación. Pero subamos la ladera y alcancemos la plataforma de piedra que se extiende como cota cero de la escenificación. Ha cambiado la escala del lugar; al Norte un muro cerrado y bajo con un pequeño paso, y al Sur, pilares de marés viejo sostienen una gran cubierta de teja a un agua y definen el límite de lo construido. Sobresaliendo de esta plataforma y enmarcando con los pilares y la cornisa un olivo centenario, se adelanta el porche cuadrado de 9 pilares: bajo él, el gran aljibe, elemento fundamental para la vida en una casa mallorquina en el campo. La obligada respuesta a una necesidad elemental e inmediata como es la de ampliar la capacidad de almacenamiento del agua de lluvia ha sido sugerencia y estímulo de la expansión y nueva expresión de la casa.

We could say that all this staging is aimed at extending the roof area to collect more rainwater and that would be true, but there is something else. We could say that the Balearic climate allows outdoor living for a large part of the year and therefore the whole extension of the porticoed area and that would be true, but there is more to it than that. We could comment on the architect’s delicate activity in building with his own hands a temporary structure so that his guests would not suffer too much from the summer heat on the flat terrace that serves as a roof over the master bedroom, and that would be true, but there is something else. Because there is an architecture integrated into the environment that responds to and creates complex relationships in dialogue with the natural landscape. Because it is in the nature of Architecture to reabsorb in it the essence of the place and to give an ordered response in time and place: a response that establishes the modification of “the new” by “the existing” and the modification of “the existing” (when seen as new) by the dialogue with “the new”; a condensed response in a new physical space that Architecture as landscape establishes.

Podríamos decir que toda esta escenificación tiene por objeto ampliar la superficie de cubierta para recoger mayor cantidad de agua de lluvia y sería cierto, pero hay algo más. Podríamos decir que el clima balear permite la vida al aire libre una gran parte del año y por ello, toda la ampliación de la zona porticada, y sería cierto. Pero hay algo más . Podríamos comentar la delicada actividad del arquitecto al construir con sus propias manos una estructura temporal para que sus invitados no sufriesen, en demasía, el calor del verano sobre la terraza plana que sirve de cubierta al dormitorio principal, y sería cierto, pero hay algo más. Porque existe una arquitectura integrada en el entorno que da respuesta y crea complejas relaciones dialogantes con el paisaje natural. Porque es de la naturaleza de la Arquitectura reabsorber en ella la esencia del lugar y dar una respuesta ordenada en un tiempo y lugar: respuesta que establece la modificación de “lo nuevo” por “lo existente” y la modificación de “lo existente” (al verse como nuevo) por el diálogo con “lo nuevo”; respuesta condensada en un nuevo espacio físico que la Arquitectura como paisaje establece.

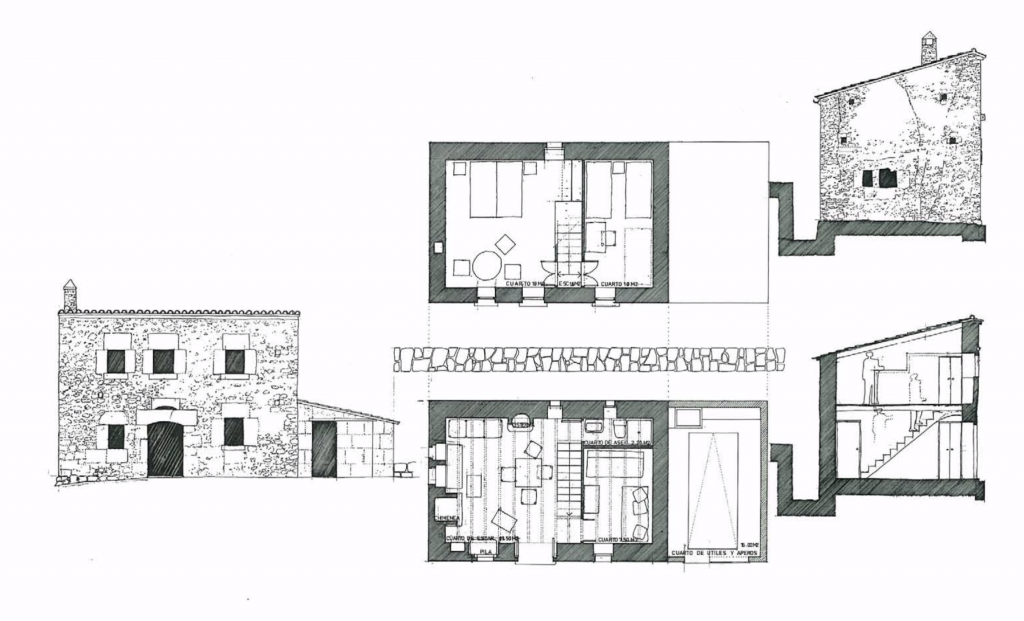

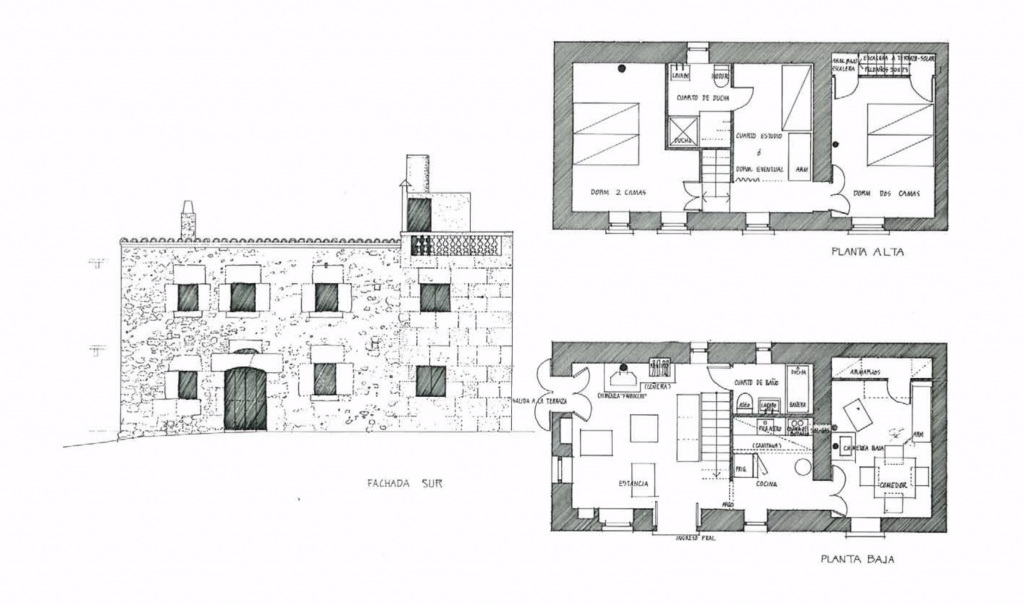

Because it is in the nature of Architecture to order the growth of Nature by synthesising a new landscape that serves as a point of reference, for humankind, of that same Nature. But let us enter the house through the door. Carved into the stone lintel is the date of its construction: 1913. We could say that we enter a square space of four by four metres in which the scale has changed again. It has diminished . That this space has, in addition to the door, two windows and a glazed door to go out laterally to the porch: the heights of the guttering are fifty centimetres, the heights of the lintels one metre seventy, to go out through the glazed door you have to lower your head… That in this same space, presided over by a cooker is the staircase that goes up to the upper floor and the doors to the bathroom and the kitchen, that beyond the “kitchenette” the dining room is found with its back converted into a pantry: an extension on the old farmyard. And that would be true, but there is more to it.

Porque es de la naturaleza de la Arquitectura ordenar el crecimiento de la Naturaleza sintetizando un nuevo paisaje que sirva de punto de referencia, para el hombre, de esa misma Naturaleza. Pero entremos en la casa por la puerta. Labrada en el dintel de piedra está la fecha de su construcción: 1913. Podríamos decir que accedemos a un espacio cuadrado de cuatro por cuatro metros en el que la escala ha vuelto a cambiar. Ha disminuido. Que este espacio tiene además de la puerta, dos ventanas y una puerta acristalada para salir lateralmente al porche: las alturas de los vierteaguas serán cincuenta cms., las alturas de los dinteles un metro setenta, para salir por la puerta acristalada hay que bajar la cabeza… Que en este mismo espacio, presidido por una estufa, está la escalera que sube a la planta alta y las puertas del baño y la cocina, que pasada la “cocinita” está el comedor con su fondo convertido en una despensa: una ampliación sobre el antiguo corral. Y sería cierto, pero hay algo más.

We could say that on the upper floor two bedrooms and a toilet above the stairwell with a pitched roof and a minimum height of one metre fifty define the old construction; that a bedroom and the staircase leading to the flat terrace define the upper floor of the extension, and all would be true, but there is more to it than that. Because there is a built architecture that offers multiple suggestions and evocations, because again, it is in the nature of Architecture to reabsorb in it the needs not only physical, but also intellectual, emotional and spiritual of man and to give an orderly response to this legion of needs consubstantial to the word house “. In this case, “the existing” allowed the architect to give shape to an approach to life that was dear to him. The house asks to be inhabited by a “citizen” of the city, not by a peasant, it asks him to be “light”, this house is not for piling up, there is no room for everything. It asks him to be “austere” in its functioning, the minimum necessities of life are covered but there is no room for a great display of furniture, only what is strictly necessary. It asks him to like solitude, the grandeur of silence; it asks him to enjoy his own landscape, in Nature, next to the rocks, on the earth, as the sentence that heads this article says “… to continue loving it” . Very probably these requests are the consequence of the search for a utopia, perhaps achievable, for the citizen of the 20th century, the return to nature without this meaning the escape from the present life.

Podríamos decir que en la planta alta dos dormitorios y un aseo encima del hueco de la escalera con la cubierta inclinada a un agua y con una altura mínima de un metro cincuenta definen la antigua construcción; que un dormitorio y la escalera de acceso a la terraza plana definen la planta alta de la ampliación, y todo sería cierto, pero hay algo más. Porque hay una arquitectura construida que ofrece múltiples sugerencias y evocaciones, porque de nuevo, es de la naturaleza de la Arquitectura reabsorber en ella las necesidades no sólo físicas, sino intelectuales, emocionales y espirituales del hombre y dar una respuesta ordenada a esta legión de necesidades consustanciales a la palabra “casa”. En este caso, “lo existente” permitió al arquitecto dar forma a un planteamiento de vida muy querido por él. La casa pide ser habitada por un “ciudadano” de la ciudad, no por un campesino, le pide que sea “ligero de equipaje”, esta casa no vale para amontonar, no cabe todo. Le pide que sea “austero” en su funcionamiento, las mínimas necesidades vitales están cubiertas pero no hay espacio para un gran despliege de muebles, sólo lo estrictamente necesario. Le pide que le guste la soledad, la grandeza del silencio; le pide que disfrute de su propio paisaje, en la Naturaleza, junto a las rocas, sobre la tierra, como dice la frase que encabeza este artículo “… para seguir amándola” . Muy probablemente estas peticiones sean consecuencia de la búsqueda de una utopía, quizá realizable, para el ciudadano del siglo XX, la vuelta a lo natural sin que ello signifique la huida de la vida actual.

The architect would like to share his understanding of the city as an extension of houses in the landscape, nostalgia for a natural order that the city must carry out in the territory. Because after all, we are only five minutes by car from Pollensa, a small distance that the natural landscape seems to extend. It asks you, in short, to inhabit it as a place of rest, as a place where man withdraws to continue living in activity. The house is so strongly impregnated with these needs that, even if someone does not share them, it is difficult to avoid them. And perhaps the greatest compliment that can be paid to the Architect “who conceives the Plan of Manifestation” is the action of inhabiting it. Moreover, such is the simplicity of the means he uses to materialise this Plan, that we might say it is in the nature of the Master to reabsorb into it all the impressions he receives and to give a response that satisfies the deeper levels of man himself. And we end this article with a beloved quote from the Architect: “One house cannot differ from another. The important thing is to know whether it is built in heaven or in hell”. (Borges).

El arquitecto querría compartir su entendimiento de la ciudad como extensión de casas en el paisaje, nostalgia de un orden natural que la ciudad debe llevar a cabo en el territorio. Porque después de todo, estamos a cinco minutos escasos en coche de Pollensa, distancia pequeña que el paisaje natural parece ampliar. Le pide, en definitiva, que la habite como lugar de reposo, como lugar en el que el hombre se retira para seguir viviendo en la actividad. Está tan fuertemente impregnada la casa de estas necesidades que, aunque alguien no las comparta, difícilmente pueda sustraerse a ellas. Y tal vez, el mayor elogio que se pueda hacer al Arquitecto “que concibe el Plan de la Manifestación” sea la acción de habitarla. Además, es tal la sencillez de medios que utiliza para materializar este Plan, que podríamos decir que es de la naturaleza del Maestro reabsorber en él todas las impresiones que recibe y dar una respuesta que satisfaga niveles más profundos del propio hombre. Y acabamos este artículo con una cita muy querida del Arquitecto: “Una casa no puede diferir de otra. Lo importante es saber si está construida en el cielo o en el infierno”. (Borges)

Madrid, February 1990. M. Luisa López Sarda and José Carlos Velasco López

VIA:

D’A n°4, 1990