This article is part of the Hidden Architecture Series “Tentative d’Épuisement”, where we explore the practice of an architectural criticism without rhetoric and based mainly on the physical experience of the work itself.

Este artículo forma parte de la serie “Tentativa de Agotamiento”, comisariada por Hidden Architecture, donde exploramos la práctica de una crítica arquitectónica ausente de retórica y fundamentada sobre todo en la experiencia física de la propia obra.

***

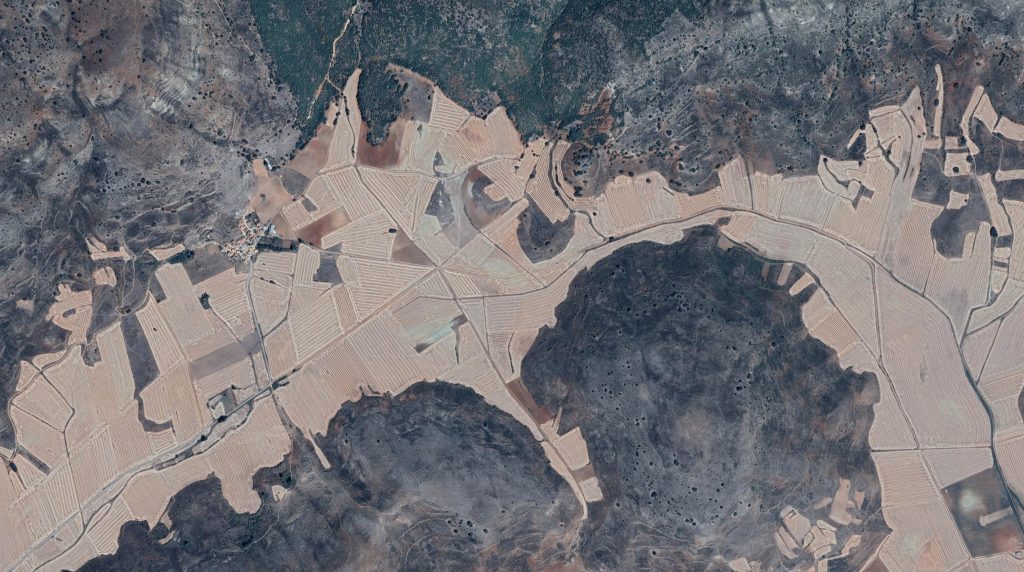

On the move for half an hour, we have not yet come across any vehicles. The road looks like a clean cut in the territory, an infinite and empty line similar to that left by a ship struggling to navigate a frozen sea before capsizing. To the left and right, the landscape displays an indiscernible range of ochre, brown and yellow tones. Earth, trees, plants and abandoned buildings merge into a folded surface of hypnotic continuity. Only the many birds that take flight here and there interrupt this static harmony. The watercourses that run through this territory have dug furrows and crevices that the vegetation has been quick to colonise. Sometimes only the treetops, now bare in winter and with branches still glistening with frost and dew, are visible from a distance. The road rises us to the top of a plateau whose boundaries are not discernible; its only limit seems to be drawn by the sky. As we wind through a narrow canyon, close to our destination, huge, coal-dark vultures take flight as we pass. High above, we discover their shelters in countless hollows that water must have left in the limestone rock thousands of years ago. Their cursed dance of the dead halted, hundreds of eyes monitor our progress through their domain. Their funereal presence makes me imagine inhabiting this land as an act of violence.

En marcha desde hace media hora, todavía no nos hemos cruzado con ningún vehículo. La carretera parece un corte limpio en el territorio, un trazo infinito y vacío similar al dejado por un barco que lucha por navegar un mar congelado antes de zozobrar. A izquierda y derecha, el paisaje despliega una gama indiscernible de tonos ocres, marrones y amarillos. Tierra, árboles, plantas y construcciones abandonadas se funden en una superficie plegada de continuidad hipnótica. Solo las múltiples aves que aquí y allá alzan el vuelo interrumpen esta armonía estática. Los cursos de agua que recorren este territorio han excavado surcos y grietas que la vegetación se apresuró a colonizar. En ocasiones solo las copas de los árboles, ahora desnudas en invierno y con las ramas aún brillantes de escarcha y rocío, son visibles desde una cierta distancia. La carretera nos eleva hasta colocarnos en lo alto de una meseta cuyos confines no se adivinan; su único límite parece dibujado por el cielo. Al serpentear por un angosto cañón, ya cerca de nuestro destino, unos buitres enormes y oscuros como el carbón alzan el vuelo a nuestro paso. En lo alto, descubrimos sus refugios en innumerables oquedades que el agua debió de dejar en la roca caliza miles de años atrás. Detenido su maldito baile de muertos, cientos de ojos controlan nuestro avance por sus dominios. Su fúnebre presencia me hace imaginar habitar esta tierra como un acto de violencia.

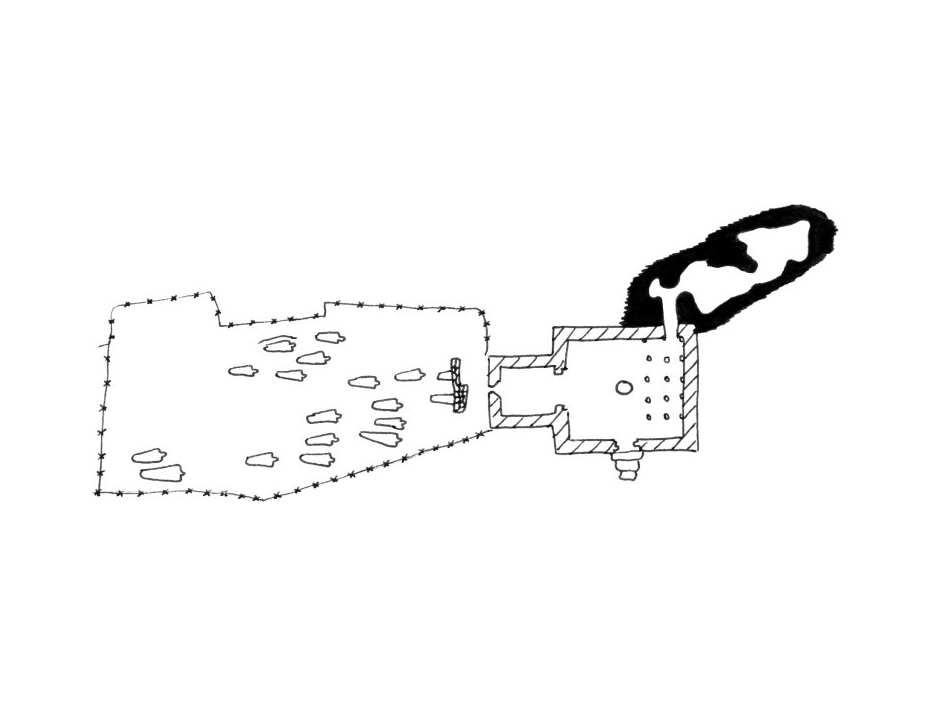

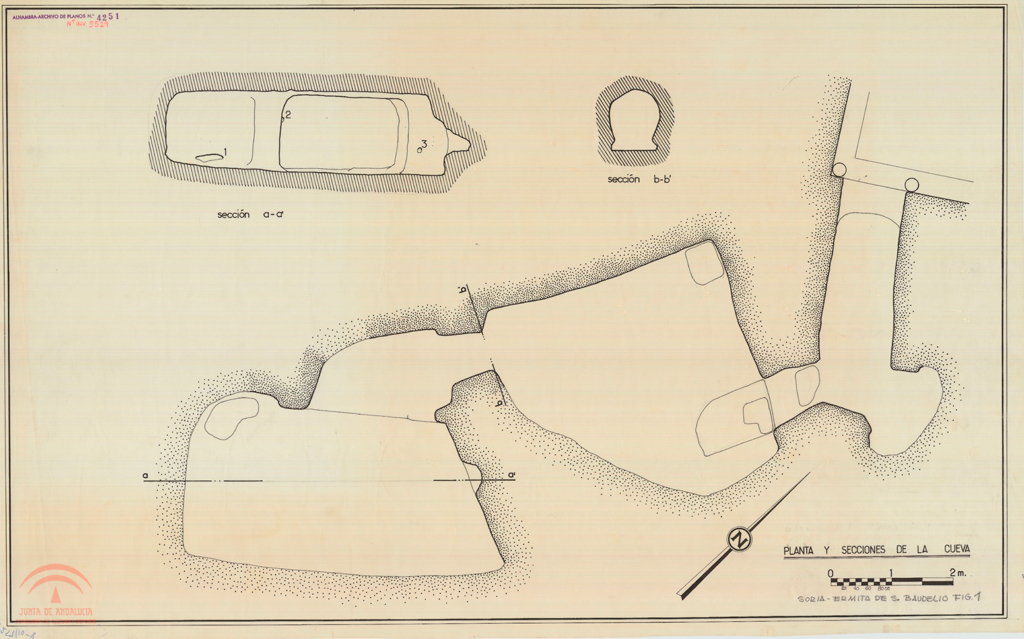

I get out of the car and the silence hurts my ears almost as much as the cold Cierzo, a wind that, despite the bright sun, does not cease its onslaught on these empty lands. The grasses and bushes swept by it melt like shadows in the distance. This place is surprising for its harshness and its stillness, but also for the anonymity of each of its elements. The hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga is no stranger to this law. Perched high up on a hillside, its completely unornamented cubic volume seems to be a vertical extension of the ground plane. An upright ochre rock, a shadow turned into light against the scourge of the wind. As we get closer, we can better distinguish its proportions and true dimensions. Two linked cubes, the smaller one hidden by the one that welcomes us, are topped by four-sided tiled roofs. The walls are smooth and massive; there is no architectural element to indicate even the primitive function of the building, when almost a thousand years ago it was erected over a grotto that probably served as a refuge for hermit monks for centuries. For a moment, the rough, recent ramps that guarantee access to the interior of the hermitage disappear. Snow and blood equally cover a land accustomed to dispute, but also to the intermingling of peoples who alter political borders in an almost pendulum-like movement. A group of monks, wrapped in rags, heat snow to turn it into water over a hesitant, recently lit fire, in front of the mouth of the cave that shelters them. The dark, organic geometry of this natural refuge isolates them from a turbulent world that they observe with impathy. Next to the cave, they have been burying their deceased companions and will soon begin the construction of a small monastic structure. Their only company is the vultures and hawks that often descend to perch beside them when an unbearable wind impedes their flight.

Desciendo del coche y el silencio me duele en los oídos casi tanto como el frío Cierzo, viento que, a pesar del sol brillante, no cesa su arremetida sobre estas tierras vacías. Las hierbas y matorrales barridos por él se funden como sombras en la distancia. Este lugar sorprende por su dureza y por su quietud, pero también por el anonimato de cada elemento que lo integra. La ermita de San Baudelio de Berlanga no es ajena a esta ley. Erguida en lo alto de una ladera, su volumetría cúbica totalmente desornamentada parece una extensión en vertical del plano del terreno. Roca ocre erguida, sombra convertida en luz frente al azote del viento. Al acercarnos distinguimos mejor sus proporciones y verdaderas dimensiones. Dos cubos enlazados, el más pequeño oculto por aquel que nos da la bienvenida, son rematados por cubiertas de teja a cuatro aguas. Los muros son lisos y masivos; no hay ningún elemento arquitectónico que nos indique ni tan siquiera la función primitiva del edificio, cuando hace casi mil años fue levantado sobre una gruta que probablemente sirvió de refugio a monjes ermitaños durante siglos. Por un momento, las toscas y recientes rampas que garantizan el acceso al interior de la ermita desaparecen. Nieve y sangre cubren por igual una tierra acostumbrada a la disputa, pero también al mestizaje de los pueblos que alteran unas fronteras políticas en un movimiento casi pendular. Un grupo de monjes, envueltos en harapos, calientan nieve para convertirla en agua sobre un dubitativo fuego recién encendido, frente a la boca de la cueva que los cobija. La geometría oscura y orgánica de este refugio natural les aísla de un mundo convulso que observan con impavidez. Junto a la cueva han ido enterrando a sus compañeros fallecidos y pronto iniciarán la construcción de una pequeña estructura monástica. Su única compañía, los buitres y halcones que a menudo descienden a posarse junto a ellos cuando un viento insoportable impide su vuelo.

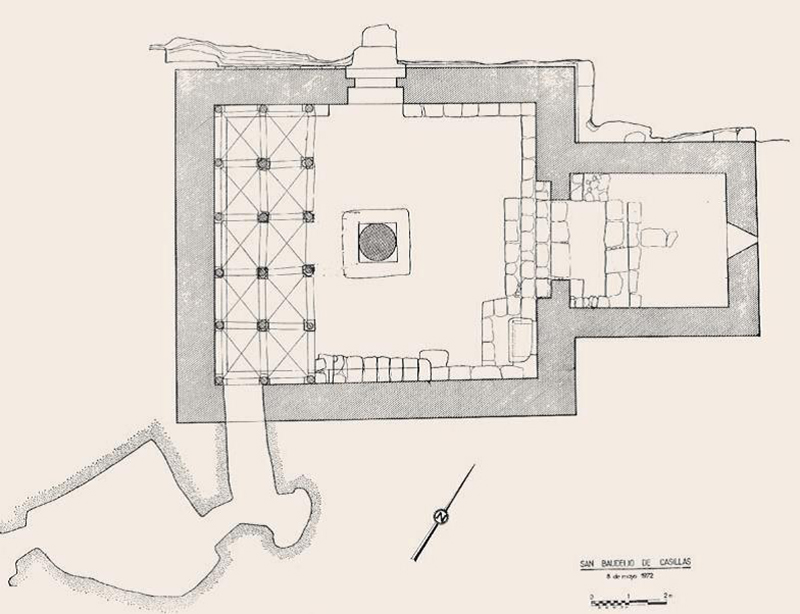

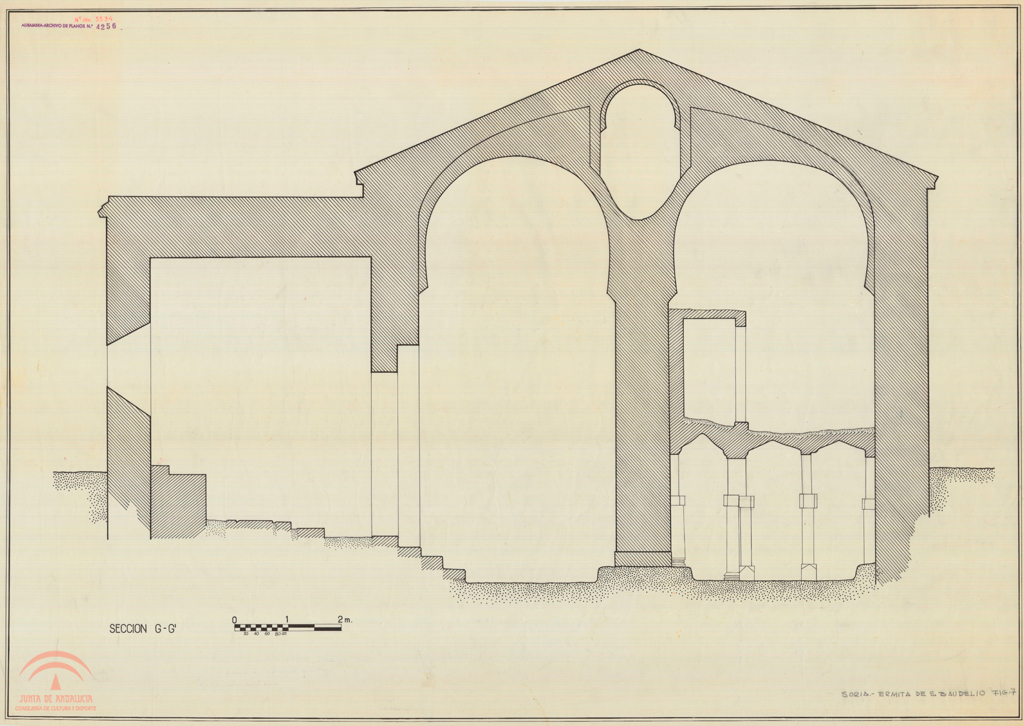

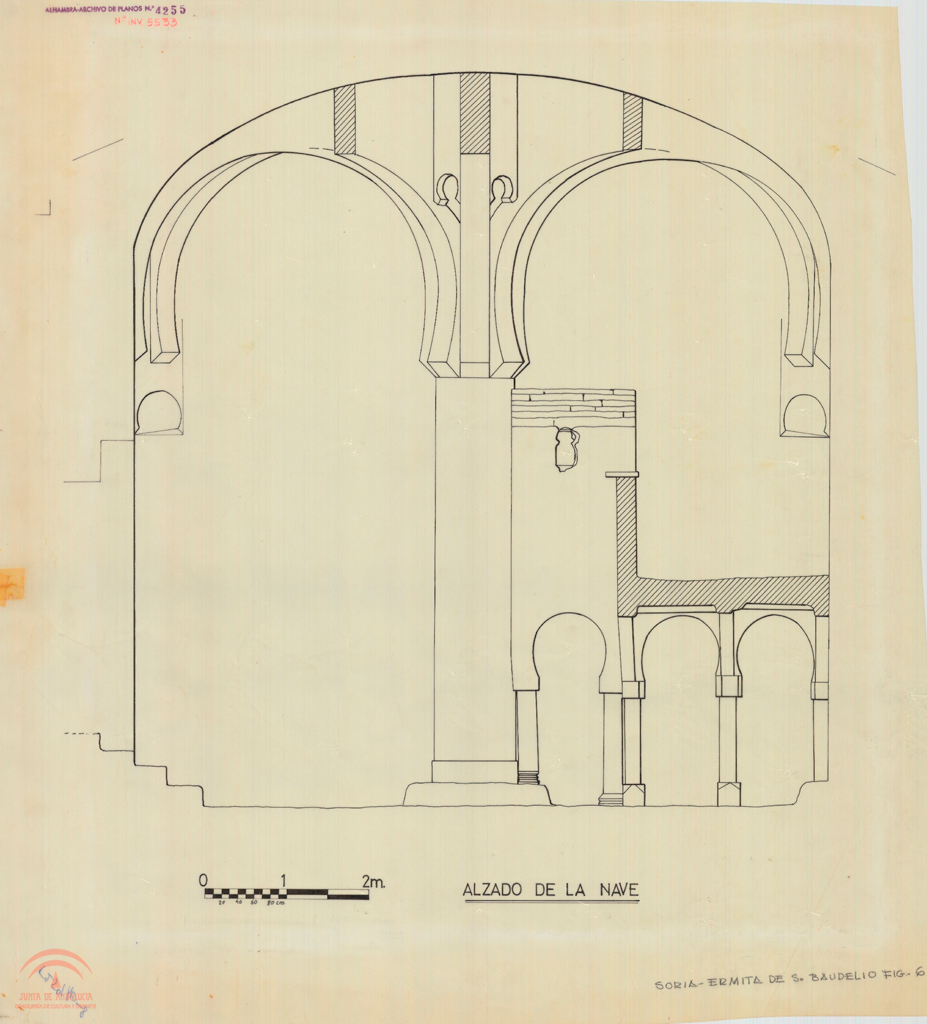

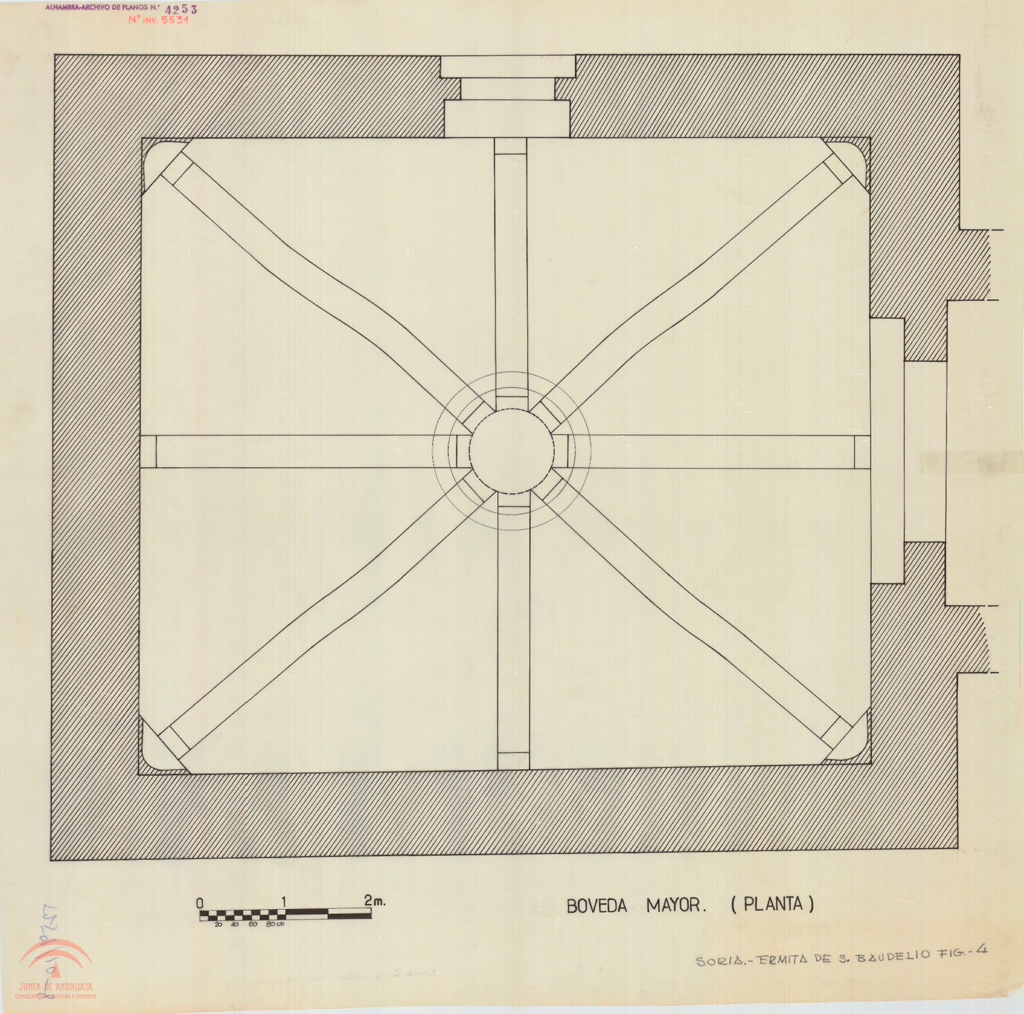

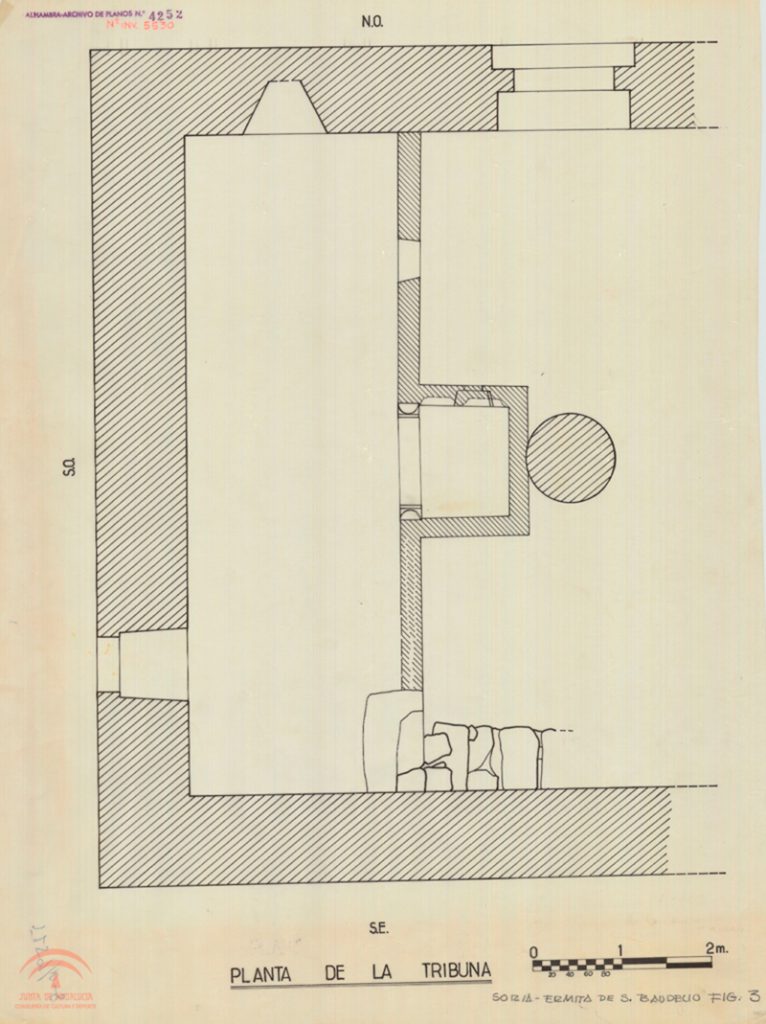

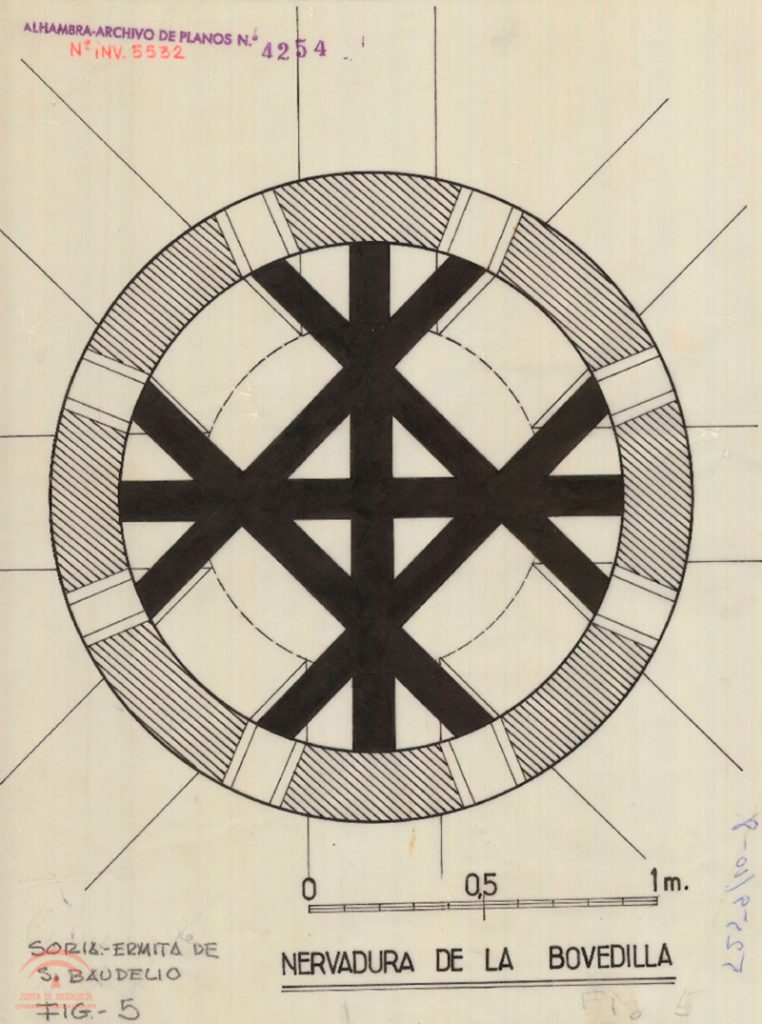

The two prismatic volumes indicate that the interior of the hermitage is composed of a single nave with an almost square floor plan and an apse added to it. Crossing the threshold of the narrow doorway, which looks more like a crack dug into the rock, confirms this layout. The main hall has almost cubic proportions. It is about eight metres wide, eight metres long and perhaps ten metres high. The floor seems to have been carved directly out of the living rock; it probably once had a pavement that was removed. In the middle of the room, an imposing column more than a metre in diameter rises from two pedestals that sprout from the ground itself. The mountainside on which this hermitage stands has hardly any trees. The constant wind that blows here makes it impossible for any species taller than a bush to grow. Inside the nave, however, the rotund central column looks like a thick palm tree enclosed by four walls, its branches clashing against a roof that is too low for it. At a certain height, from six metres upwards, the trunk of the palm tree splits into eight horseshoe arches that rest, at opposite ends, on the thick masonry walls that protect us from the outside. The vaults of the roof are thus supported by this structural ensemble, offering a spatial framework of powerful presence. The dimensions of each of the elements that make up the structure seem excessive; but at the same time of an almost brutal honesty when it comes to expressing this displacement from the living tree to the frozen tree in stone. Its almost telluric weight, the force of gravity that draws us insistently towards the ground carved out of the rock itself, which prevents us from almost lifting our feet as we walk, rubbing awkwardly against the ground, dragging, on the contrary, generates a surprising sensation of lightness. It is as if the strong character of the structural elements were congesting, tensing the space deeply around them in order to liberate that other space which they do not occupy, which appears grandiose despite its reduced dimensions. This spatial activation by opposites, together with the equally violent contrast between light and shadow, produced by the almost complete absence of openings, gives this chapel a mystical atmosphere.

Los dos volúmenes prismáticos indican que el interior de la ermita está compuesto de una sola nave de planta casi cuadrada y un ábside a ella añadido. Cruzamos el umbral de la estrecha puerta, que más bien parece una grieta excavada en la roca, y confirmamos esta disposición. La sala principal presenta unas proporciones casi cúbicas. Sus dimensiones rondan los ocho metros de ancho, ocho metros de largo y quizá diez de altura. El suelo parece directamente labrado sobre roca viva, seguramente en algún momento tuvo un pavimento que fue arrancado. En el medio de la sala, imponente, una columna de más de un metro de diámetro se eleva gracias a dos pedestales que brotan del propio terreno. La ladera de la montaña sobre la que se levanta esta ermita no disfruta apenas de la presencia de ningún árbol. El viento constante que aquí sopla imposibilita el crecimiento de cualquier especie más alta que un matorral. En el interior de la nave, sin embargo, la rotunda columna central parece una gruesa palmera encerrada por cuatro paredes; sus ramas chocando contra una techumbre demasiado baja para ella. Y es que a determinada altura, a partir de los seis metros, el tronco de la palmera se divide en ocho arcos de herradura que se apoyan, en sus extremos opuestos, en los gruesos muros de mampostería que nos protegen del exterior. Las bóvedas de la cubierta quedan así sostenidas por este conjunto estructural, ofreciendo un marco espacial de potente presencia. Las dimensiones de cada uno de los elementos que componen la estructura parecen excesivos; pero al mismo tiempo de una honestidad casi brutal a la hora de expresar ese desplazamiento desde el árbol vivo al árbol en piedra congelado. Su peso casi telúrico, la fuerza de la gravedad que nos atrae insistente hacia ese suelo labrado sobre la propia roca, que nos impide casi levantar los pies al caminar, rozando torpemente con el firme, arrastrándose, genera por el contrario una sensación de liviandad sorprendente. Es como si el fuerte carácter de los elementos estructurales congestionase, tensionara el espacio profundamente a su alrededor para liberar aquel otro espacio que no ocupan, que se muestra grandioso a pesar de lo reducido de sus dimensiones. Esta activación espacial por opuestos, junto con el contraste también violento entre luz y sombra, producido por la ausencia casi absoluta de aperturas, dota a esta capilla de una atmósfera mística.

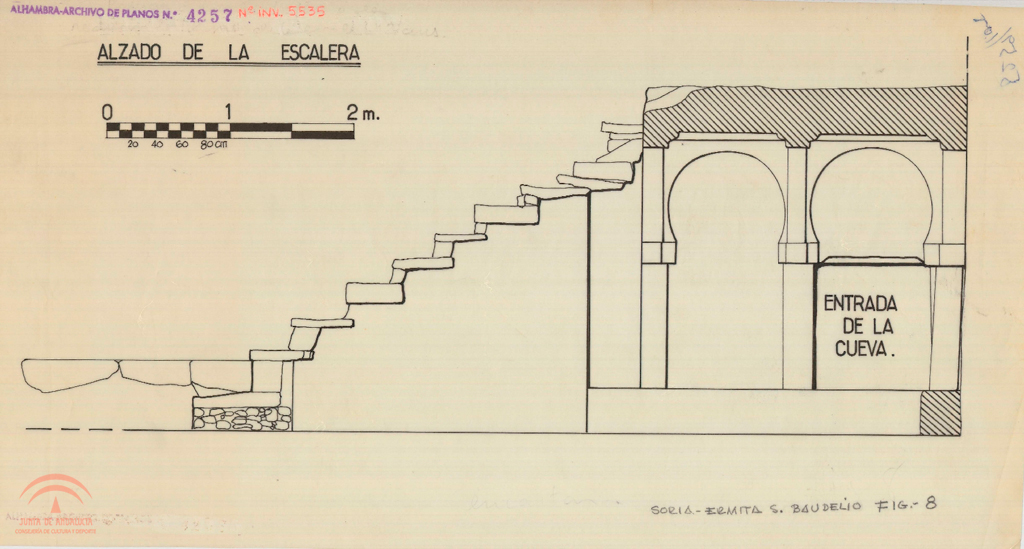

The main nave of San Baudelio, as mentioned above, of almost cubic proportions, is divided into two halves by the presence of the central column. The part on the left, the void under the branches, houses the altar and is connected to the apse by steps. On the wall opposite the entrance, cantilevered stone stairs, embedded in the wall like spears on a soft body, lead in a dance of shadows and air to the upper part of the choir. If this left side is emptiness and light, the right half of the nave is shadow, weight, matter. Eighteen columns, in a matrix of three by six and separated from the surrounding wall in a gesture of emancipating modernity, support, with the help of the arches that illuminate, the high choir with exhausted effort. If the upper part, the path of ascent on the false elastic tension of spears that are stone, is ethereal light, the space defined by the colonnade is the descent into the abyss of shadows, into the dampness impregnated in the walls of the cave that the hermits inhabited in the distant past. Taking care not to bump my head on any of the capitals that articulate column and arch, I move cautiously through the shadows and admire how the dim light inside this forest, filtered through the crack in the main door, confirms my perception of how light this heavy space seems.

La nave principal de San Baudelio, como hemos dicho anteriormente de proporciones casi cúbicas, queda dividida en dos mitades por la presencia de la columna central. La parte de la izquierda, el vacío bajo las ramas, acoge el altar y se conecta con el ábside mediante unos escalones. En la pared opuesta a la entrada, unas escaleras de piedra en voladizo, incrustadas en el muro como lanzas sobre un cuerpo mullido, conducen en un baile de sombras y aire hasta la parte superior del coro. Si esta parte izquierda es vacío y luz, la mitad derecha de la nave es sombra, peso, materia. Dieciocho columnas, en matriz de tres por seis y separadas del muro que las rodea en un gesto de modernidad emancipadora, sostienen, con ayuda de los arcos que alumbran, el alto coro con agotado esfuerzo. Si la parte superior, el camino de ascenso sobre la falsa tensión elástica de unas lanzas que son piedra, es luz etérea, el espacio definido por la columnata es el descenso al abismo de las sombras, a la humedad impregnada en los muros de la cueva que los eremitas habitaron en un pasado ya muy lejano. Procurando no golpear mi cabeza con alguno de los capiteles que articulan columna y arco, me muevo con cautela entre las sombras y admiro cómo la luz tenue en el interior de este bosque, filtrada a través de la grieta de la puerta principal, confirma mi percepción de lo ligero que parece este espacio tan pesado.

The simplicity of its exterior forms might have led us to think that San Baudelio de Berlanga was no more than a cattle shed, built by anonymous hands to protect the sheep from the cold night of the plateau. Nevertheless, for centuries, this hermitage, abandoned and isolated from any important event, nobly fulfilled that function. However, in the case of this building, a statement is always followed by its opposite. On the outside, the rock is raised and placed with a certain constructive order, although without any showiness; as if to show a gesture that exceeds its simple function as a refuge would be reprehensible. Inside, the walls, columns, arches and vaults are canvases for the narration of stories, support for paintings of different types which, like works of goldsmithing, illuminate rock and shadows. The hermitage is colour in vibration, a polychromatic space of overwhelming sensorial richness. Today, only the unconnected remains of paintings that were originally a continuous fresco covering the interior of San Baudelio remain. These are sufficient, however, to illuminate, to set tree and cave ablaze.

La sencillez de sus formas exteriores nos podría haber hecho pensar que San Baudelio de Berlanga no era más que un cobertizo para ganado, construido por manos anónimas para proteger a las ovejas de la gélida noche mesetaria. No obstante, durante siglos esta ermita, abandonada y apartada de todo acontecimiento importante, cumplió con nobleza esa función. Sin embargo, en el caso de este edificio una afirmación siempre viene seguida de su contrario. En el exterior, la roca es levantada y colocada con cierto orden constructivo, aunque sin alardes; como si mostrar un gesto que excediese su simple función de refugio fuera censurable. En el interior, los muros, columnas, arcos y bóvedas son lienzos para la narración de historias, soporte para pinturas de diferentes facturas que, como obras de orfebrería, iluminan roca y sombras. La ermita es color en vibración, un espacio policromático de una riqueza sensorial abrumadora. En la actualidad solo quedan restos inconexos de pinturas que en su origen fueron un fresco continuo, cubriendo el interior de San Baudelio. Éstas son suficientes, sin embargo, para iluminar, encender en llamas árbol y cueva.

Before leaving, we heard that at the beginning of the 20th century, when the building was already protected by Patrimonio Nacional, it was sold for a derisory sum to an art dealer. After local residents tried to stop the looting, the sale was declared legal by the courts and the interior frescoes were torn out and scattered to different museums in the United States. To complete the story, Franco’s fascist dictatorship negotiated their return to Spain in exchange for the Romanesque apse of a church in Segovia in the 1950s.

Antes de salir escuchamos que a principios del siglo XX, con el edificio ya protegido por Patrimonio Nacional, éste fue vendido por una cantidad irrisoria a un marchante de arte. Después de que los vecinos de la zona trataran de detener el expolio, la venta fue declarada legal por la justicia y los frescos interiores fueron arrancados para terminar dispersados por diferentes museos de Estados Unidos. Para completar la historia, la dictadura fascista de Franco negoció su regreso a España a cambio del ábside románico de una iglesia segoviana en la década de los cincuenta.

December 29th, the year 2021. Part of the paintings lie forgotten in some corner of the Prado Museum, Madrid, some two hundred kilometres away and ten degrees warmer than here. The apse given in exchange for recovering them is on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The stones that compose it, dismantled, shipped and reassembled thousands of kilometres away, languish withering away, oblivious to the environment that gave them meaning; probably impassive to the spectacle generated by commerce and the voracious consumption of art. In San Baudelio de Berlanga, in front of us and behind the altar, two oxen beat their antlers in a duel. The smiling expression on their faces fails to dissipate the tension of the encounter. Their skin, vividly incarnated, contrasts with the ultramarine blue border that serves as the sky of the scene and the base of the wall.

Veintinueve de diciembre, año 2021. Parte de las pinturas descansan olvidadas en algún rincón del Museo del Prado, Madrid, a unos doscientos kilómetros y diez grados de temperatura más que aquí. El ábside entregado a cambio para recuperarlas se encuentra expuesto en el Metropolitan Museum de Nueva York. Las piedras que lo componen, desmontadas, embarcadas y reensambladas a miles de kilómetros languidecen marchitándose ajenas al entorno que las otorgó sentido; probablemente impasibles ante el espectáculo generado por el comercio y el consumo voraz de arte. En San Baudelio de Berlanga, frente a nosotros y tras el altar, dos bueyes baten su cornamenta en duelo. La expresión risueña de su cara no logra disipar la tensión del encuentro. Su piel, vivamente encarnada, contrasta con la cenefa azul ultramarino que hace las veces de cielo de la escena y de basamento del muro.

The wind hits me from behind, pushing me downhill. The low December sun plays timidly with some high clouds, giving off a weak light, weak but still capable of discomforting the eyes. White brushstrokes of gypsum adorn like snow the crests of the mountains eroded by water and wind, now almost flat at the top. From the air, a group of vultures draw circles of invisible smoke, casting their long, grey shadows over the easternmost foothills of the plateau on which we are standing. San Baudelio, for those who do not know the brilliant interior of its forest, is but a slight alteration of the rocky surface of the terrain.

El viento me golpea de espaldas empujándome cuesta abajo. El sol bajo de diciembre juega tímido con unas nubes altas, desprendiendo así una luz débil, débil pero aún capaz de incomodar los ojos. Pinceladas blancas de yeso adornan como nieve las crestas de los montes erosionados por agua y viento, ya casi planos en su remate superior. Desde el aire, un grupo de buitres dibujan círculos de humo invisible, arrojando su sombra gris y alargada sobre las estribaciones más orientales de la meseta que pisamos. San Baudelio, para aquellos que desconocen el brillante interior de su bosque, no es más que una ligera alteración de la superficie rocosa del terreno.