Geographical context

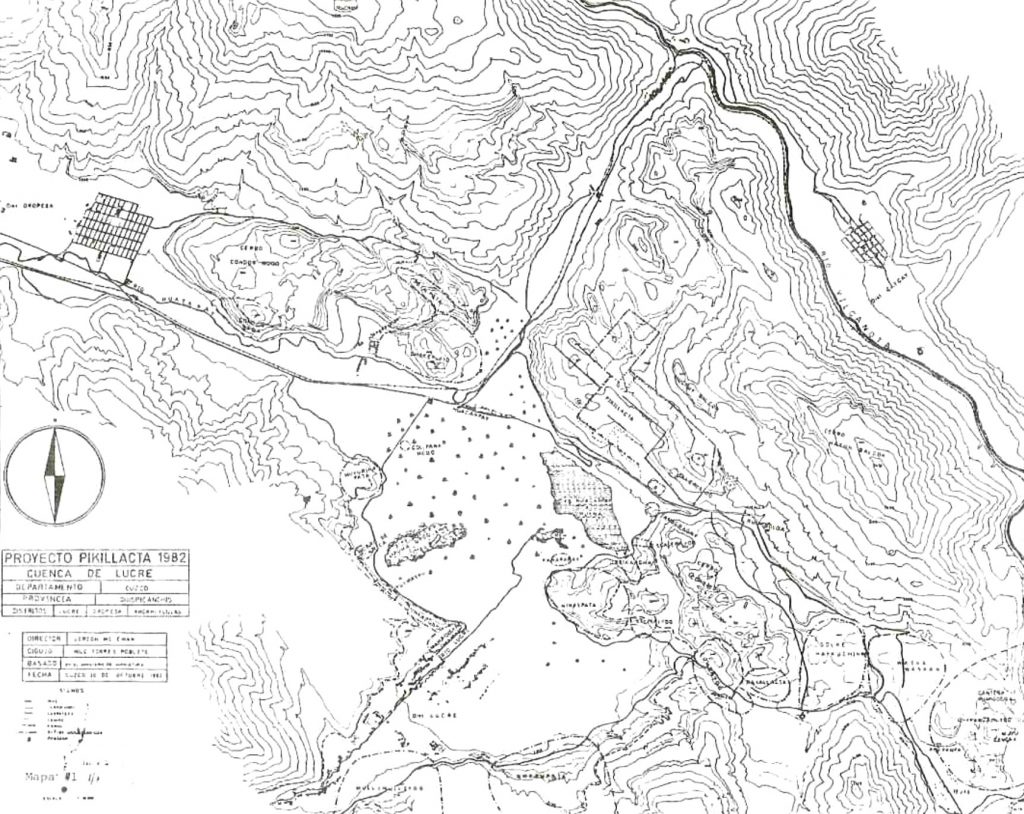

The settlement of Pikillaqta is located in the hills of the eastern valley of Cuzco on the Lucre basin, some thirty kilometres away from the Andean capital and at an altitude of approximately 3250 metres above sea level. Slightly removed from the greenery and fertility that the Hurubamba river brings to the Sacred Valley, it is located in a hilly landscape known today as the South Valley, because of its position in relation to the most touristic sector of the valley, that which extends northwards between Cuzco and Machu Picchu. Unlike most of the Inca or pre-Inca cities found in the area, Pikillaqta (Quechua for ‘city of fleas’) did not develop in the area of influence of a river. However, the Huacarpay wetland can be found in its vicinity. From a geographical point of view, this area is of fundamental strategic importance. Its slightly elevated position on the slope of the Huchuy Balcón hill allowed its inhabitants to visually control three different valleys: the upper Vilcanota valley, the lower Vilcanota valley and the Quispicanchis valley. In addition to the representative function that this great city had for the Wari Empire – a civilisation prior to the Incas that developed in the territory of Peru, specifically in the Andean area of Ayacucho – its location at the intersection of the different valleys mentioned above made it an area of great maize production, the fundamental sustenance of the Andean communities. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that the secondary function of the city of Pikillaqta was to store consumer goods, an essential circumstance that would define its urban and architectural structure. Finally, we could indicate that it enjoyed a territorial relevance on a much larger scale, as the natural passage of the valleys eroded by different rivers constituted the communication route between the Peruvian Andean highlands, the Cuzco region and, beyond that, the Puneño highlands and Lake Titicaca.

El asentamiento de Pikillaqta se encuentra en las lomas del valle oriental de Cuzco sobre la cuenca del Lucre, a unos treinta kilómetros de distancia de la capital andina y una altitud aproximada de 3250 metros sobre el nivel del mar. Ligeramente apartado del verdor y la fertilidad que el río Hurubamba proporciona al valle Sagrado, se ubica en un paisaje de lomas conocido actualmente como el valle Sur, a causa de su posición en relación al sector del valle más turístico, aquel que se extiende hacia el Norte entre Cuzco y Machu Picchu. Al contrario de lo que sucede en la mayoría de las ciudades de origen inca o pre-inca halladas en la zona, Pikillaqta (en quechua, ciudad de las pulgas) no se desarrolló en la zona de influencia de un río. En sus proximidades sí se puede encontrar, sin embargo, el humedal Huacarpay. Desde un punto de vista geográfico, esta zona tiene una importancia estratégica fundamental. Su posición ligeramente elevada sobre la ladera del cerro Huchuy Balcón permitió a sus habitantes controlar visualmente tres valles diferentes: el valle alto del Vilcanota, el valle bajo del Vilcanota y el valle de Quispicanchis. Junto a la función representativa que esta gran ciudad tuvo para el Imperio Wari – civilización previa a los Incas que se desarrolló en el territorio de Perú, concretamente en el área andina de Ayacucho – su ubicación en la intersección de los diferentes valles anteriormente citados la convirtió en una zona de gran producción de maíz, sustento fundamental de las comunidades andinas. Se han encontrado indicios suficientes para pensar que la función secundaria de la ciudad de Pikillaqta fue la de almacenar bienes de consumo, circunstancia esencial que definirá su estructura urbana y arquitectónica. Por último, podríamos indicar que disfrutó de una relevancia territorial a escala mucho mayor, pues el paso natural de los valles erosionados por diferentes ríos constituye la vía de comunicación entre el altiplano andino peruano, la región de Cuzco y, más allá, el altiplano Puneño y el lago Titicaca.

Cultural context

The city of Pikillaqta is the most developed urban example of the Wari, a society which, given the complex urban structure found, must have been efficiently organised. The site was probably built as a residence for the political and religious elites in the southernmost territories of the pre-Inca empire, with the aim of operating as an administrative centre, as well as exercising their responsibility for territorial control derived from their logistical function of food storage.

La ciudad de Pikillaqta es el ejemplo más desarrollado a nivel urbano de los Wari, sociedad que, a razón de la compleja estructura urbana hallada, debía de estar eficientemente organizada. El sitio fue probablemente construido como residencia de las élites políticas y religiosas, en los territorios más meridionales del imperio pre-inca, con el objetivo de operar como centro administrativo, además de ejercer su responsabilidad en el control territorial derivada de su función logística de almacenamiento de alimentos.

Considering the archaeological finds, it is estimated that it was built between 540 and 900 AD, a period known as the Middle Horizon in the Wari culture. Established in the area of Ayacucho, a region that until then had been relatively marginal in the context of the Central Andes, the Wari civilisation is evidence of a fundamental step from previous societies, fundamentally theocratic, towards models in which the economic and social spheres would have a much greater hierarchy. In addition to its undoubted anthropological value, this evolution also defines a change in the urban and architectural paradigm. From settlements where large constructions dedicated to the worship of the gods were the basis of urban life, there was a move towards other models where civil power was manifested in a greater number of smaller-scale buildings, forming an urban fabric based on the repetition of minimal units. The use of these housing modules generates an urban fabric capable of resolving administrative, political, productive, ceremonial and residential functions, following the organisational scheme of urban space defined by the warrior elites. This pre-planning process was notably reflected in the city of Pikillaqta, which was built at a later date. In contrast, in the capital of the Wari civilisation in Ayacucho, the archaeological remains found show a disorderly urban growth and evolution that responded spontaneously to the need to accommodate a larger population. It could thus be argued that in the capital of the Wari Empire there is no evidence of planned physical development, the main characteristic of the city of Pikillaqta.

Considerando los hallazgos arqueológicos encontrados, se estima que fue construida entre el 540 y el 900 d.C., época conocida como Horizonte Medio en la cultura wari. Implantada en la zona de Ayacucho, región hasta ese momento relativamente marginal en el contexto de los Andes Centrales, la civilización wari evidencia un paso fundamental desde sociedades anteriores, fundamentalmente teocráticas, hacia modelos donde las esferas económicas y sociales tendrían una jerarquía mucho mayor. Además de su valor antropológico indudable, esta evolución define asimismo un cambio en el paradigma urbano y arquitectónico. Desde asentamientos donde grandes construcciones dedicadas al culto de los dioses eran la base de lo urbano, se avanza hacia otros modelos donde el poder civil se manifiesta en un mayor número de edificaciones de menor escala, constituyendo un tejido urbano a partir de la repetición de unidades mínimas. La utilización de estos módulos habitacionales genera una trama urbana capaz de resolver las funciones administrativas, políticas, productivas, ceremoniales y residenciales, siguiendo el esquema de organización del espacio urbano definido por las élites waris. Este proceso de planificación previa quedará notablemente plasmado en la ciudad de Pikillaqta, de ejecución ya tardía. Por el contrario, en la capital de la civilización wari en Ayacucho, los restos arqueológicos encontrados muestran un crecimiento y evolución urbana desordenada que responde espontáneamente a las necesidades de albergar más población. Se podría argumentar así que en la capital del Imperio Wari no se encontrarán evidencias que manifiesten un desarrollo físico planificado, característica principal de la ciudad de Pikillaqta.

This urban planning developed by the Wari, also present in other settlements of lesser importance but built at the same time as Pikillaqta, was one of the fundamental tools used to establish the political power of the state over the territory. Having already commented on the importance of the location of this city, it seems logical to think that the officials in charge of its planning must have had a deep and specific knowledge of the surrounding physical context, as well as the climatic conditions and the trade routes and connections with other distant territories.

Este urbanismo desarrollado por los Wari, presente también en otros asentamientos de menor relevancia pero ejecutados simultáneamente a Pikillaqta, constituye una de las herramientas fundamentales para implantar el poder político del Estado sobre el territorio. Habiendo comentado ya previamente la importancia de la ubicación de esta ciudad, parece lógico pensar que los funcionarios a cargo de su planificación debieron de poseer un conocimiento profundo y concreto del contexto físico circundante, así como de las condiciones climáticas y de las rutas y conexiones comerciales con otros territorios lejanos.

Urban structure

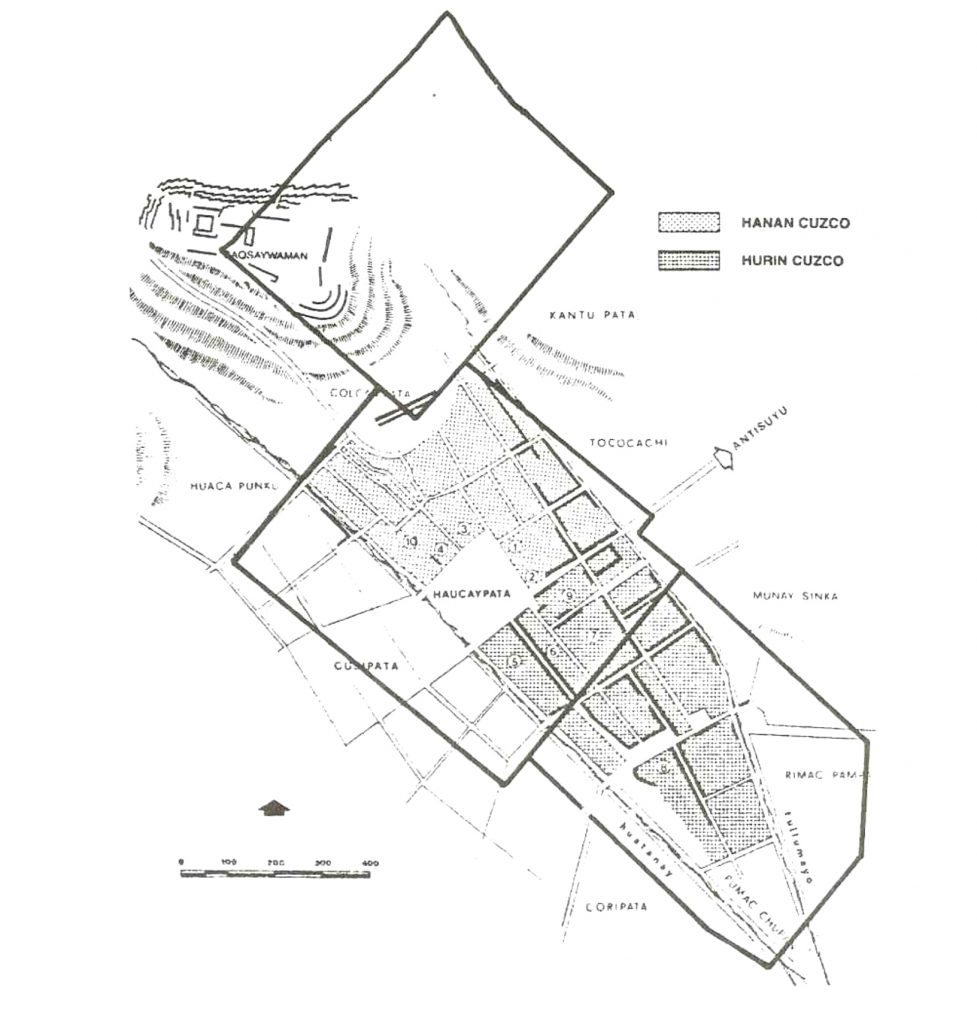

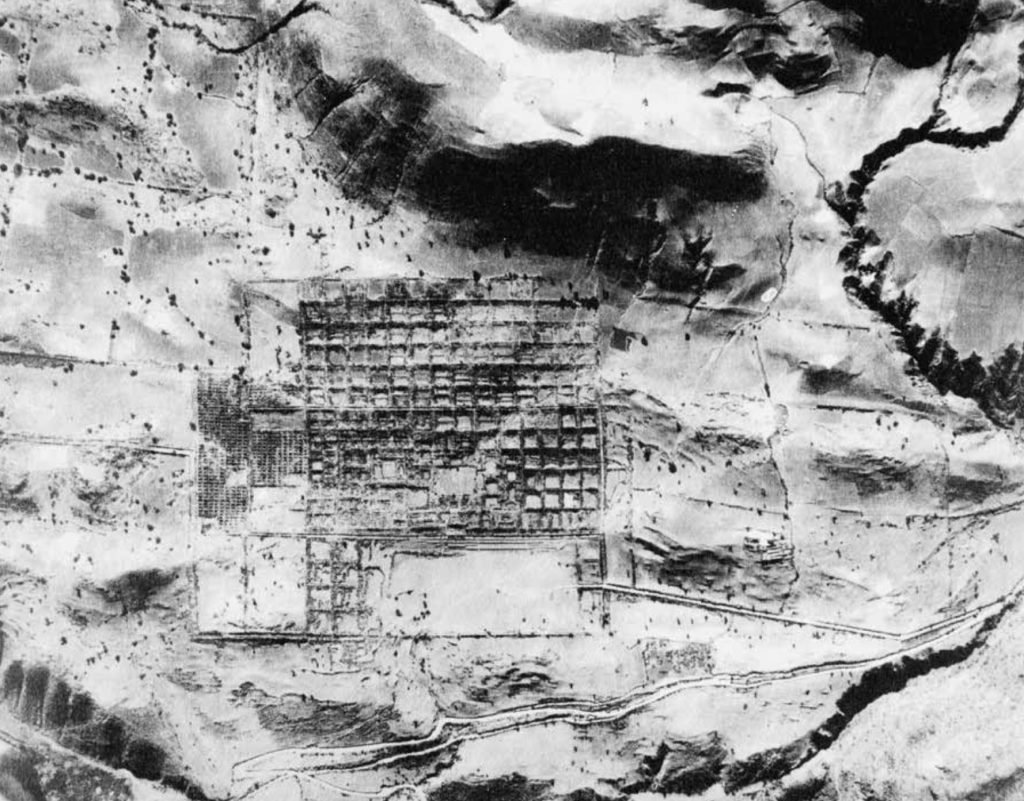

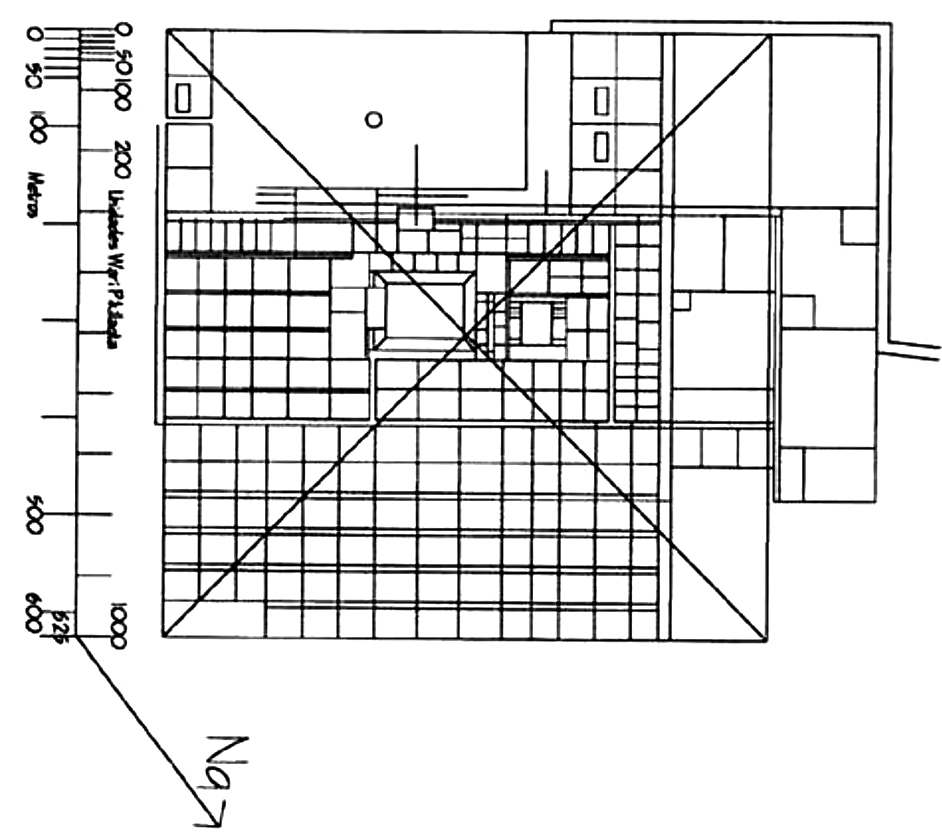

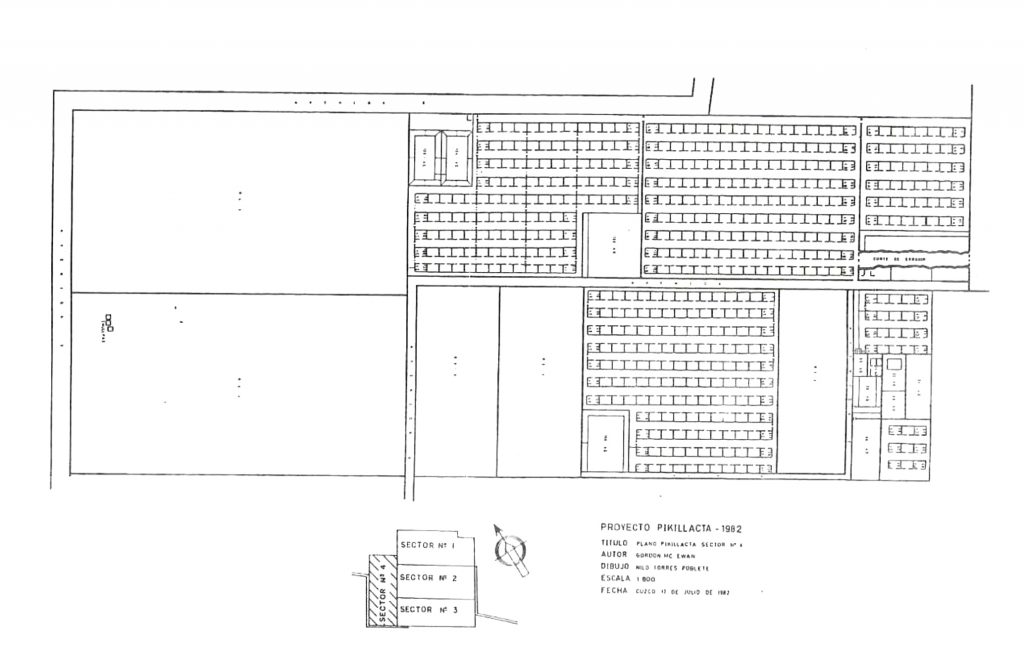

The city of Pikillaqta came to cover an area of 200 hectares, with its fortified nucleus covering an area of 745 by 630 metres. For reference, it is interesting to note that the extension of the Pikillaqta wari would be very similar to the Inca Cuzco, the capital and main city of the Andean empire. Approximately rectangular in plan, it is visibly divided into three sectors, a pattern determined by the physical structure of the settlement itself. At first glance, it can be seen that Pikillaqta is developed from the repetition of a unit of quadrangular proportions in two perpendicular directions, generating an orthogonal grid that adapts flexibly to the surrounding topography. Whether it was due to a lack of technical resources or to an appreciation and enhancement of the original relief, the founders of the city made no attempt here to modify the terrain.

La ciudad de Pikillaqta llegó a comprender una superficie de 200 hectáreas, abarcando su núcleo fortificado un área de 745 por 630 metros. A modo de referencia, es interesante tener en cuenta que la extensión de la Pikillaqta wari sería muy similar al Cuzco inca, capital y principal ciudad del imperio andino. De planta aproximadamente rectangular, está visiblemente dividida en tres sectores, patrón determinado por la propia estructura física del asentamiento. A simple vista se observa que Pikillaqta se desarrolla a partir de la repetición de una unidad de proporciones cuadrangulares en dos direcciones perpendiculares, generando un damero ortogonal que se adapta a la topografía del entorno con flexibilidad. Ya fuera por falta de recursos técnicos o por una apreciación y puesta en valor del relieve original, los fundadores de la ciudad no realizaron ningún intento aquí de modificar el terreno.

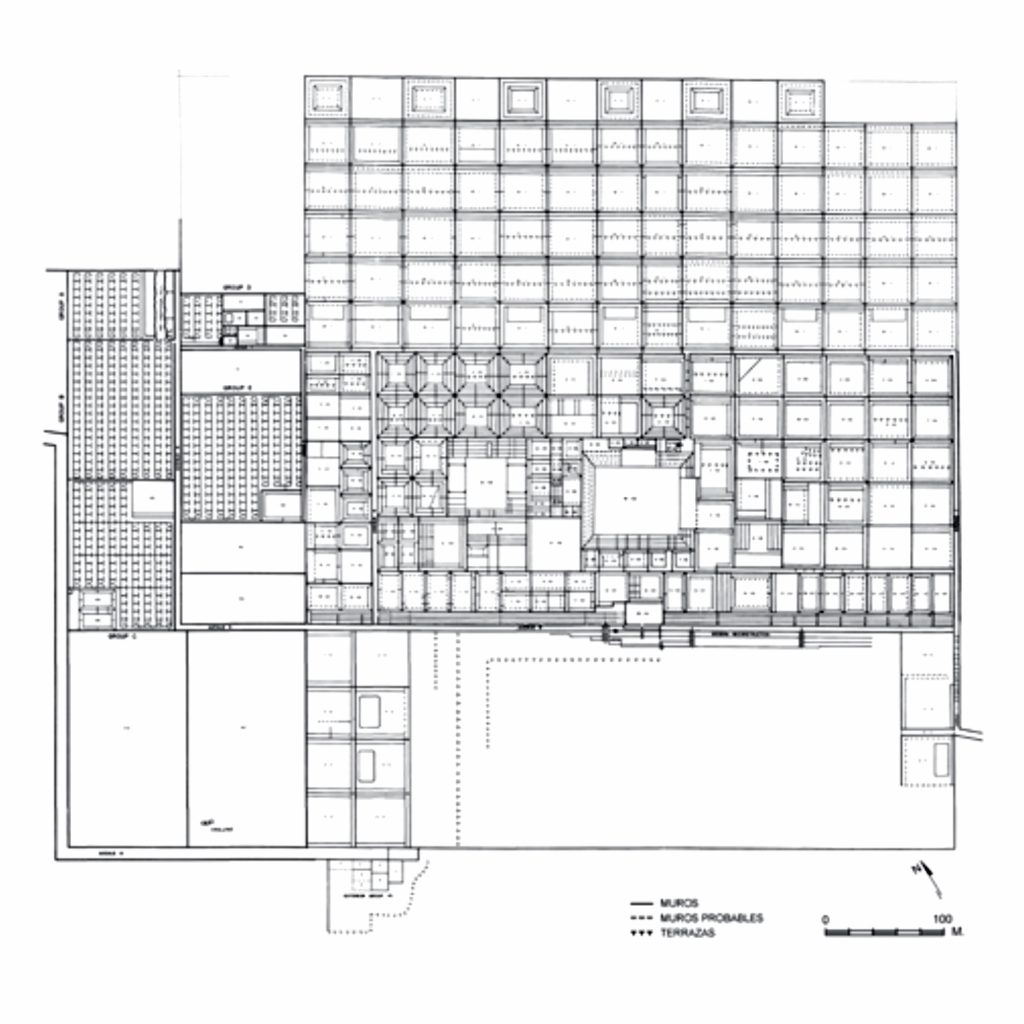

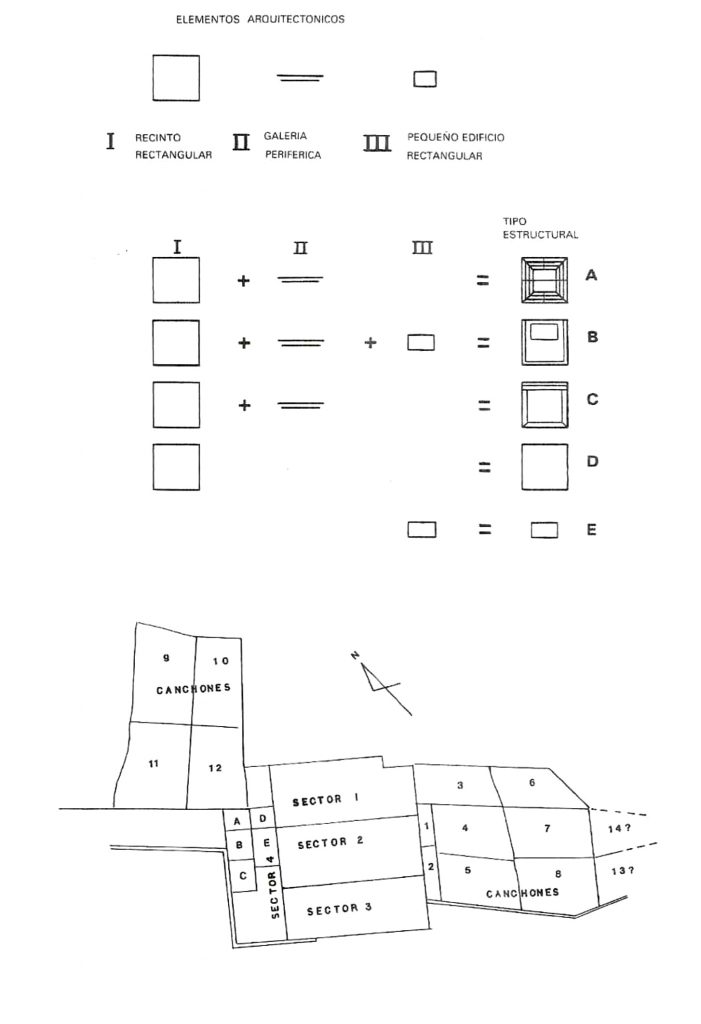

A more detailed study would reveal that the settlement of Pikillaqta is based on the use of three architectural elements or patterns. The first of these would be the fortified rectangular enclosure, with the formal rotundity typical of urban planning aimed at dominating a territory. According to archaeological evidence, it is likely that the Wari civilisation built the city from the outside in, i.e. the first thing they defined on the territory was the outer limit materialised in the perimeter wall. This fact is fundamental for understanding the value of the urban planning they developed, as it would imply that the layout of the different elements, or at least the interior grid structure, must have been planned before construction began. We would thus find ourselves before an example analogous to modern urban planning, carried out from the top down or from the general to the particular; and not before an organic growth by repetition of a basic urban structure, as the Wari had built their previous settlements.

Un estudio algo más pormenorizado revelaría que el asentamiento de Pikillaqta se basa en la utilización de tres elementos o patrones arquitectónicos. El primero de ellos sería el recinto rectangular fortificado, con la rotundidad formal propia de un planeamiento urbano dirigido a dominar un territorio. Según muestran los indicios arqueológicos, es probable que la civilización wari construyera la ciudad desde fuera hacia adentro, es decir, que lo primero que definieran sobre el territorio fuese el límite exterior materializado en la muralla perimetral. Este hecho es fundamental para comprender el valor de la planificación urbana que desarrollaron, ya que implicaría que la disposición de los diferentes elementos, o al menos la estructura interior en cuadrícula, debió de estar proyectada antes de iniciarse su construcción. Nos encontraríamos así ante un ejemplo análogo a los planeamientos urbanos modernos, realizados desde arriba hacia abajo o desde lo general a lo particular; y no frente a un crecimiento orgánico por repetición de una estructura urbana básica, tal y como los Wari habían construido sus asentamientos previos.

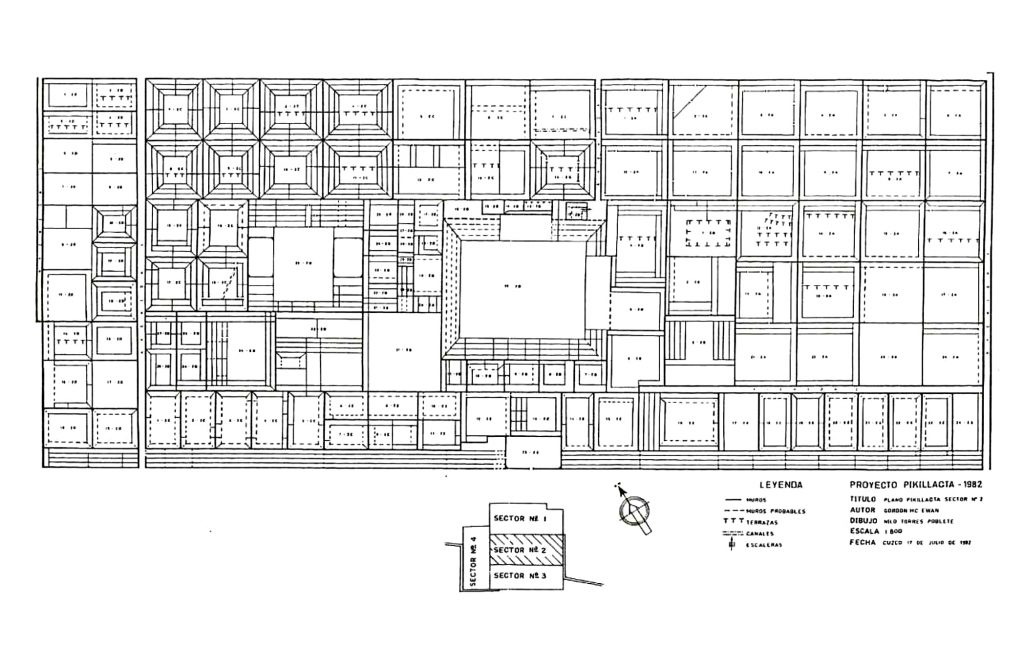

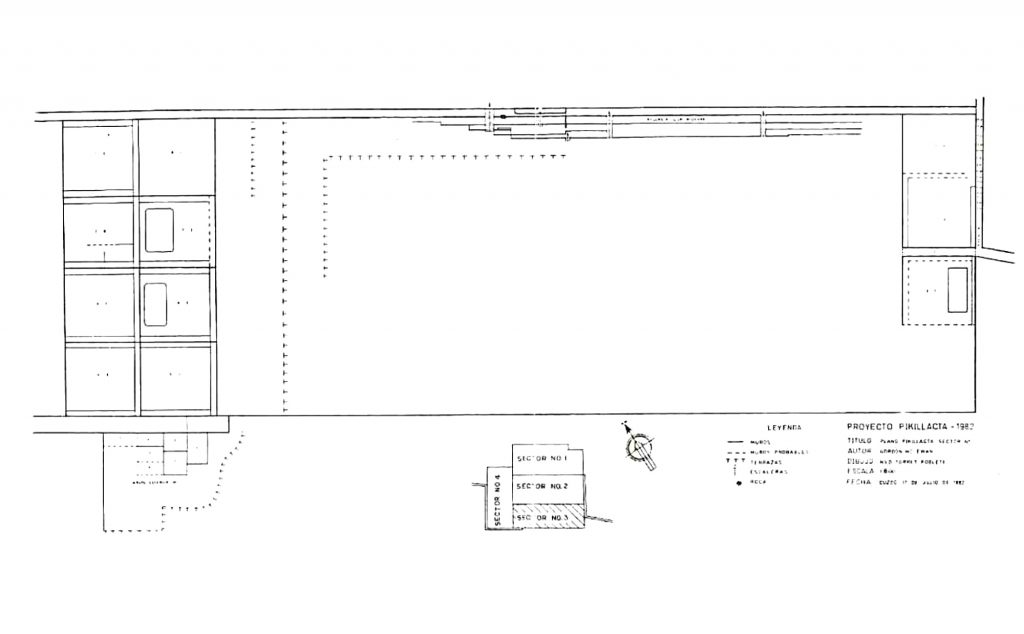

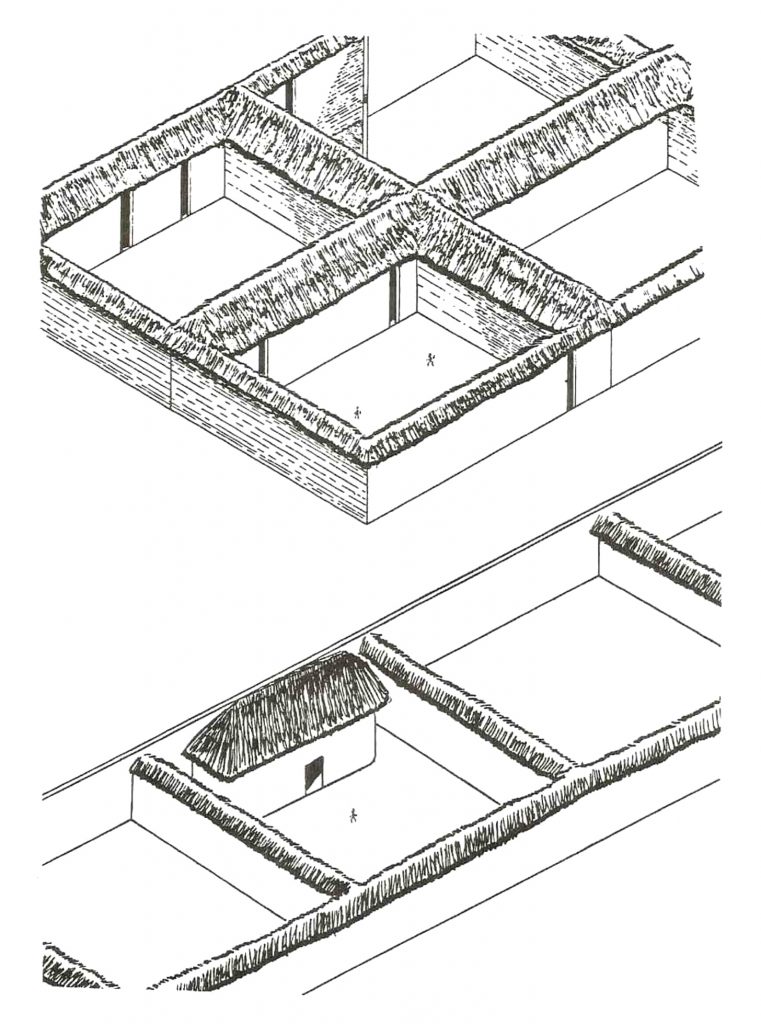

Secondly, we would consider the peripheral circulation gallery. Despite the fact that the urban structure could present certain parallels with the Roman city from a formal point of view, the hierarchical organisation of the roads and thus the establishment of circulations and operability differ notably. In Pikillaqta there are no main axes which, crossing perpendicularly, define a hierarchical centre. On the contrary, the main circulation route will be the perimeter one, that is, the one defined inside the walls by the outer wall. From this ring, a series of secondary roads are laid out which define the three sectors into which the city is divided. These sectors could be defined as superblocks with a clearly defined external circulation. However, their large dimensions and the almost complete absence of an internal road network make it difficult to foresee how the circulations within each sector would be organised. It is necessary to consider that the construction of walls, from the main perimeter wall to those that progressively define the sectors and each of the minimum units of the grid, defines a structure that could be considered fractal. This strategy determines an isotropic urban space in which, apparently, it would have been difficult to find one’s way around and move around. The very closed nature of the different levels of walls, with hardly any openings in them, together with the hypothetical absence of an internal distributing road, are fundamental in shaping the urban space.

En segundo lugar consideraríamos la galería periférica de circulación. A pesar de que la estructura urbana podría presentar ciertos paralelismos con la ciudad romana desde un punto de vista formal, la jerarquización del viario y así el establecimiento de las circulaciones y la operatividad difieren notablemente. En Pikillaqta no hay unos ejes principales que, cruzados perpendicularmente, definan un centro jerárquico. Por el contrario, la vía principal de circulación será la perimetral, es decir, aquella que quedaría definida a intramuros por la muralla exterior. A partir de este anillo, se trazan una serie de vías secundarias que definen los tres sectores en los que se divide la ciudad. Estos sectores podrían definirse como unas supermanzanas con una circulación exterior claramente definida. Sin embargo, las grandes dimensiones que presentan y la ausencia casi por completo de una red de viario interno dificultan prever cómo se organizarían las circulaciones dentro de cada sector. Es necesario contemplar que la construcción de murallas, desde la principal perimetral hasta las que progresivamente y en el interior definen los sectores y cada una de las unidades mínimas de la cuadrícula, define una estructura que podríamos considerar fractal. Esta estrategia determina un espacio urbano isótropo en el que, aparentemente, habría resultado complicado orientarse y desplazarse. El carácter muy cerrado de los diferentes niveles de murallas, no se aprecian apenas aperturas en ellas, junto a la hipotética ausencia de un viario distribuidor interno resultan fundamentales a la hora de conformar el espacio urbano.

Another fundamental aspect to consider in order to understand the urban structure would be the water supply. It seems necessary that the city of Pikillaqta, assuming its size, the estimated population it would have housed and its political hierarchy, would have had a system that would have allowed for the uninterrupted distribution of water. The main hypothesis in this respect is that there must have been a network of canals on a territorial scale that transported water from different points in the region to the city. The fortified structure of Rumiqolqa, still present on the outside of the quadrangular perimeter, functioned as a water supply aqueduct as well as an external fortress and symbolic gateway to the urban area of Pikillaqta. Evidence has also been found that the city had an underground sewage system superimposed on the road layout.

Otro aspecto fundamental a considerar para comprender la estructura urbana sería el abastecimiento de agua. Se antoja necesario que la ciudad de Pikillaqta, asumiendo sus dimensiones, la población estimada que alojaría y su jerarquía política, contase con algún sistema que permitiera la distribución de agua de manera ininterrumpida. La principal hipótesis al respecto señalaría que debió de existir una red de canales a escala territorial que transportasen el agua desde diferentes puntos de la región hasta la ciudad. La estructura fortificada de Rumiqolqa, todavía presente en el exterior del perímetro cuadrangular, funcionó como acueducto proveedor de agua al mismo tiempo que de fortaleza exterior y puerta simbólica de acceso al área urbana de Pikillaqta. Se han localizado además evidencias de que la ciudad contaba con una red de saneamiento enterrada superpuesta al trazado del viario.

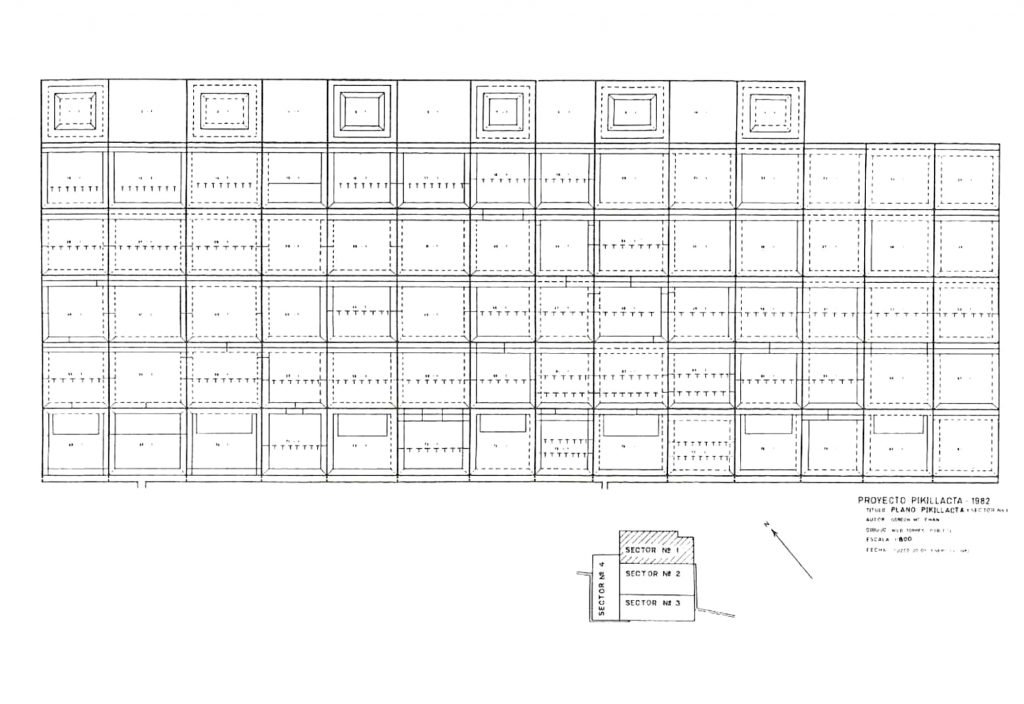

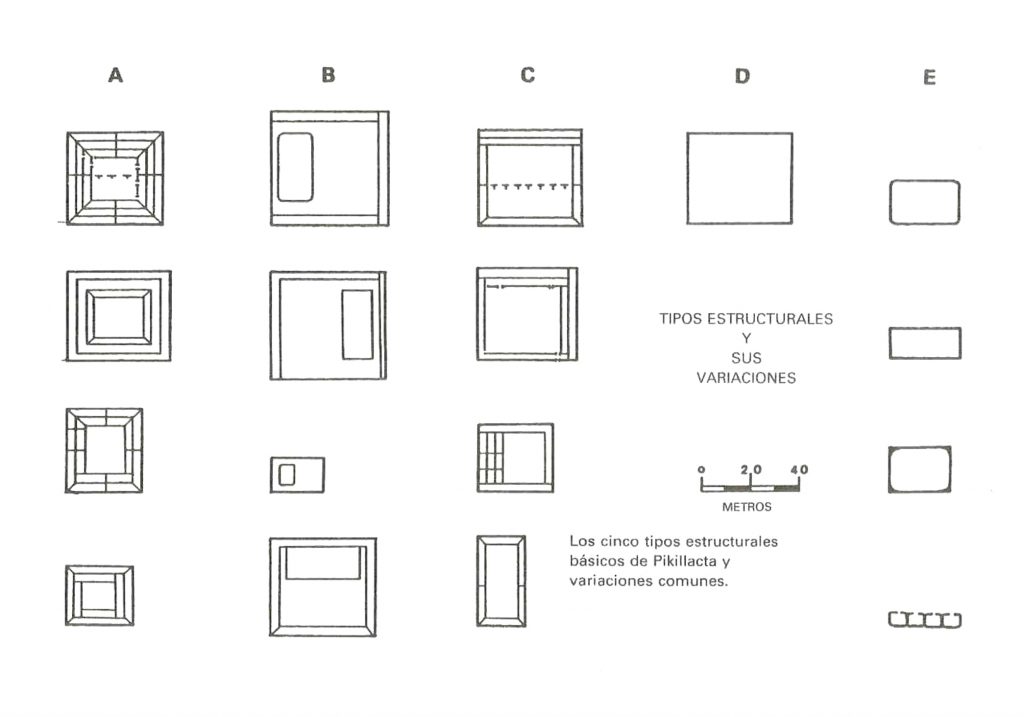

Finally, the third fundamental architectural pattern is the fenced modular unit, the kancha, which would define by repetition the urban grid structure of each sector. These modules have a very well-defined formal structure, with a central courtyard dedicated to housing community activities and a perimeter gallery construction defining its limits by means of successive bays. This basic structure evolves in different variations that would have housed all the necessary activities in the Wari city of Pikillaqta due to their polyvalence. Each kancha has dimensions ranging between 70×70 and 50×50 metres. Although it is not possible to clearly discern this fact at present, it could be deduced that the construction of the perimeter fortified galleries of each module would also imply the layout of a circulation network. In some cases, especially in the central sector, which would have housed public spaces of representation and the main administrative buildings, it can be seen that there is a free space between the different kanchas, the walls having been built in duplicate and thus creating narrow streets for circulation and possible access between them. In other cases, the majority of them, the boundaries overlap in the layout of a single wall and the kanchas extend continuously. One might wonder whether, in this case, the circulations would be through the upper level of the roof inside each sector.

Por último, el tercer patrón arquitectónico fundamental es la unidad modular cercada, el kancha, que definiría por repetición la estructura urbana en cuadrícula de cada sector. Estos módulos presentan una estructura formal muy bien definida, con un patio central dedicado a alojar las actividades comunitarias y una construcción perimetral en galería definiendo sus límites mediante sucesivas crujías. Esta estructura básica evoluciona en diferentes variaciones que albergarían por su polivalencia todas las actividades necesarias dentro de la ciudad wari de Pikillaqta. Cada kancha tiene unas dimensiones que oscilan entre los 70×70 y 50×50 metros. A pesar de que no es posible discernir con claridad este hecho en la actualidad, se podría deducir que la construcción de las galerías fortificadas perimetrales de cada módulo implicaría además el trazado de una red de circulación. En algunos casos, especialmente en el sector central, aquel que albergaría espacios públicos de representación y los edificios administrativos principales, se aprecia que entre los diferentes kanchas hay un espacio libre, habiéndose construido los muros duplicados y surgiendo así entre ellos estrechas calles de circulación y posible acceso. En otros casos, la mayoría, los límites se superponen en el trazado de un solo muro y los kanchas se extienden de manera continua. Cabría preguntarse si, en ese caso, las circulaciones se realizarían por el nivel superior de cubierta en el interior de cada sector.

In the northern sector, a typological variation of the kanchas was found, resulting in smaller units connected by avenues. There are two different hypotheses to explain this variable. The first of these, probably already discarded by the latest archaeological finds, states that this part of the city functioned as a deposit for materials. The second, developed after evidence of domestic life was found, suggests that these modules housed temporary domestic spaces, probably a prison. Assuming the latter as valid, it seems appropriate to ask how the resource storage system would then function in the city, since we must not forget that one of the main functions of Pikillaqta was to serve as a repository for goods. The latest hypothesis in this respect, developed by the architect Carlos Williams, argues that many of the kanchas would indeed be made up of different bays of galleries, thus densifying and growing from the perimeter and inwards, occupying and progressively reducing the central courtyard. Furthermore, it seems logical to think that many of these structures would have been several storeys high. In this way, it is understood that the most peripheral bays, away from the inner courtyard and therefore without natural lighting, would have housed the storage function. The kanchas are therefore multifunctional architectural patterns with great potential for evolution and growth.

En el sector Norte se halló una variación tipológica de los kanchas que dará lugar a unas unidades de menores dimensiones conectadas por avenidas. Existen dos hipótesis diferentes que explicarían esta variable. La primera de ellas, seguramente ya descartada por los últimos hallazgos arqueológicos, enuncia que esta parte de la ciudad funcionaba como depósito de materiales. La segunda, desarrollada después de haber hallado evidencias de vida doméstica en ella, propondría que estos módulos albergarían espacios domésticos temporales, seguramente una prisión. Asumiendo esta última como válida, parece oportuno preguntarse cómo funcionaría entonces en la ciudad el sistema de almacenamiento de recursos, pues no debemos olvidar que una de las funciones principales de Pikillaqta era la de servir como depósito de bienes. La última hipótesis al respecto, desarrollada por el arquitecto Carlos Williams, argumenta que muchos de los kanchas estarían efectivamente compuestos por diferentes crujías de galerías, densificándose y creciendo así desde el perímetro y hacia dentro, ocupando y reduciendo progresivamente el patio central. Además, parece lógico pensar que muchas de estas estructuras contarían con varias plantas de altura. De esta forma, se entiende que las crujías más perimetrales, alejadas del patio interior y por tanto sin iluminación natural, habrían albergado la función de almacenamiento. Los kanchas constituyen por tanto unos patrones arquitectónicos multifuncionales con gran potencial de evolución y crecimiento.

In conclusion, we could define the construction process of the wari city of Pikillaqta as a collision between two opposing models of generation of urban structures that give rise to a settlement of great complexity and interest. On the one hand, we would find the definition of a previous urban planning and project understood from a modern perspective, as evidenced by its urban structure, its settlement in the territory and its relationship on a territorial scale with distribution and supply infrastructures. On the other hand, the use of the kanchas as minimum modular units of the urban structure determined an organic growth in small doses, through operations of repetition and adaptation once the urban enclosure of Pikillaqta and its basic infrastructures, such as walls, sectors, sanitation and main avenues, were established. Despite having developed the capacity to plan urban development with large-scale territorial implications, the Wari civilisation did not want to give up the flexibility and responsiveness to the unexpected that the use of kanchas offered. The combination of these two strategies would define a complex system of internal circulations that has not yet been fully deciphered.

A modo de conclusión, podríamos definir el proceso de construcción de la ciudad wari de Pikillaqta como una colisión entre dos modelos opuestos de generación de estructuras urbanas que alumbran un asentamiento de gran complejidad e interés. Por un lado, nos encontraríamos con la definición de un planeamiento y proyecto urbano previo entendido desde una perspectiva moderna, como evidencian su estructura urbana, su asentamiento en el territorio y su relación a escala territorial con infraestructuras de distribución y abastecimiento. Por otro lado, la utilización de los kanchas como unidades modulares mínimas de la estructura urbana determinó un crecimiento orgánico a pequeñas dosis, mediante operaciones de repetición y adaptación una vez que el recinto urbano de Pikillaqta y sus infraestructuras básicas, como murallas, sectores, saneamiento y principales avenidas, quedaron establecidos. A pesar de haber desarrollado la capacidad de planificar un desarrollo urbano con implicaciones territoriales a gran escala, la civilización wari no quiso renunciar a la flexibilidad y capacidad de respuesta frente a lo imprevisto que la utilización de los kanchas les ofrecía. La combinación de estas dos estrategias definiría un complejo sistema de circulaciones internas no descifrado completamente en la actualidad.

FURTHER LITERATURE:

- Canziani Amico, José. “Ciudad y Territorio en los Andes: Contribuciones a la Historia del Urbanismo Prehispanico”. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru, Fondo Editorial, 2017

- McEwan, Gordon. “Excavaciones en Pikillaqta. Un Sitio Wari”. Dialogo Andino n°4, 1985. Departamento de Historia y Geografia de Tarapaca, Arica-Chile