“It’s too rare for Mexicans, but maybe it starts a new regional tradition. Most mortals, perhaps, have their home for a castle, but architects often considers theirs as a laboratory. Just to test ideas about housing, they are able to eat in caves, use pedestal chairs, sleep in underground vaults and grow gardens.”

“Es demasiado rara para los mexicanos, pero a lo mejor inicia una nueva tradición regional. La mayoría de los mortales, quizá, tenga su casa por un castillo, pero el arquitecto a menudo considera la suya como un laboratorio. Para poner a prueba sus ideas sobre la vivienda, él y su familia son capaces de comer en semicuevas, usar sillas de pedestal, dormir en recámaras subterráneas y cultivar jardines murales.”

Juan O’Gorman

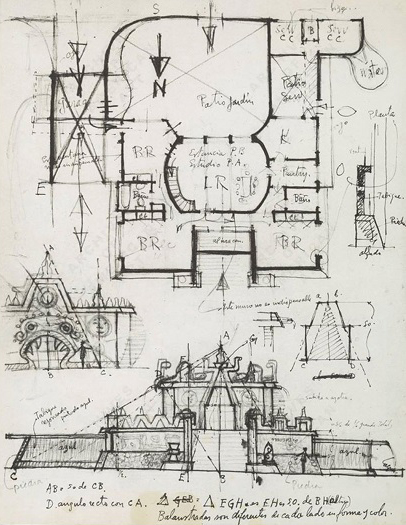

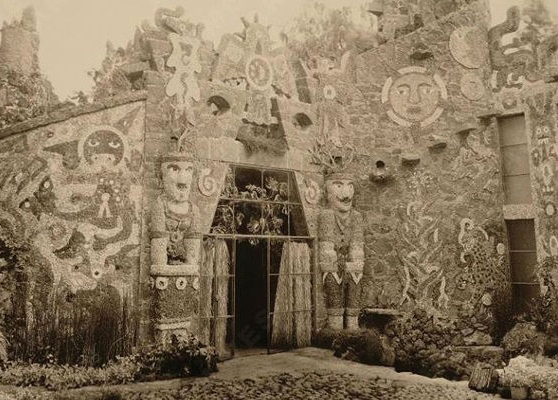

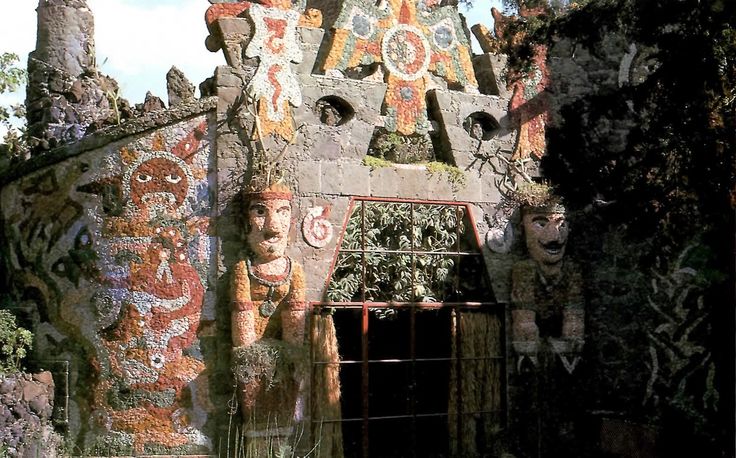

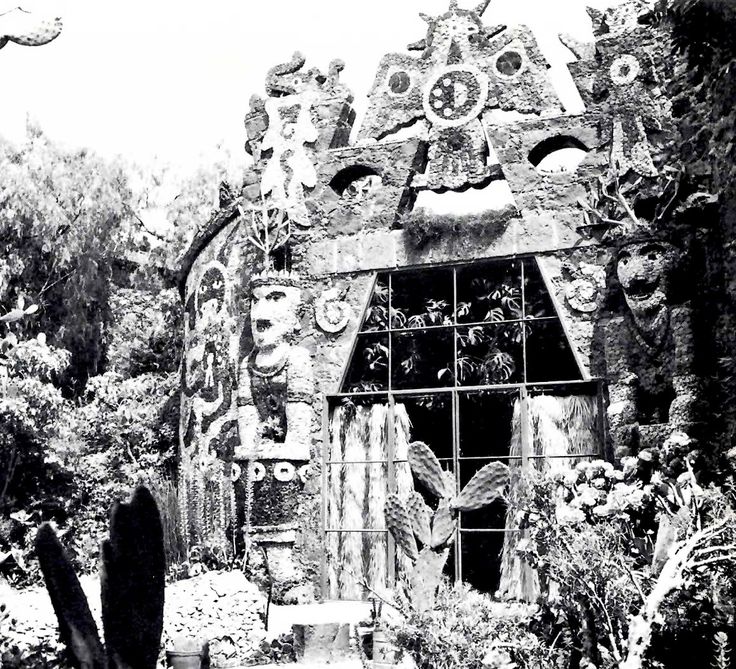

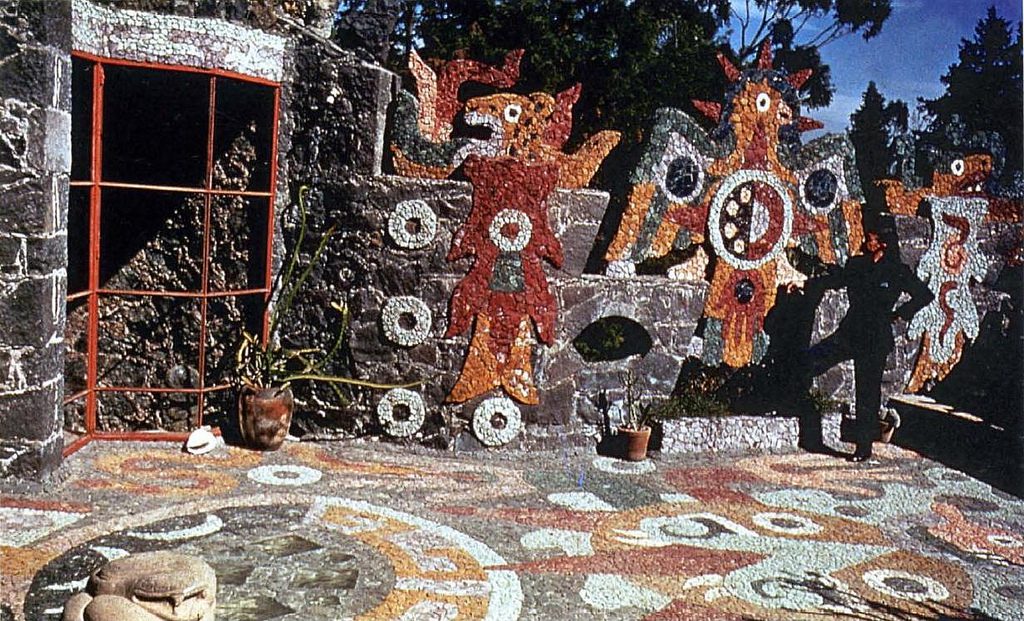

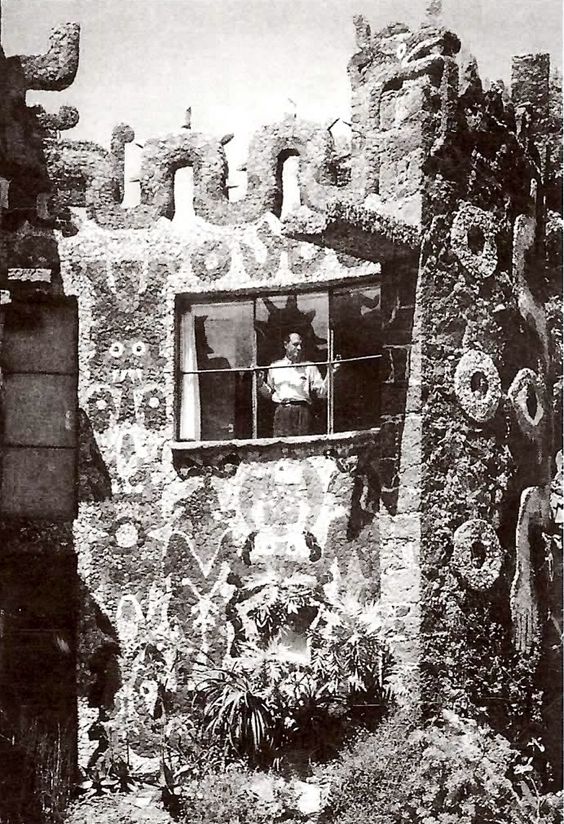

Juan O’Gorman, arquitecto mexicano, comienza su carrera profesional de la mano de Le Corbusier y su “Hacia una arquitectura” (1923), o más específicamente, de su lectura muy particular del revolucionario texto. A él se debe la construcción de la primera casa funcionalista en México en 1929, seguida de una serie de escuelas caracterizadas por una desnudez y frugalidad sin parangón incluso en la misma propuesta le corbusierana. Posteriormente y gracias a sus relaciones con la intelectualidad revolucionaria nacional, puso en práctica su propuesta funcionalista en la construcción de algunas casas privadas, de entre las que destacan las realizadas para los pintores Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo en 1932. Sin embargo después de esta efervescencia funcionalista de los años treinta O’Gorman se desconecta completamente de la disciplina arquitectónica para dedicarse a su pasión por la pintura mural y de caballete. En los últimos años de la década de los cuarenta comenzó a explorar nuevas técnicas en la pintura mural introduciendo el uso de los mosaicos policromados realizados con pierdas extraídas de distintas regiones del país.

Juan O’Gorman, Mexican architect, began his professional career with Le Corbusier and his “Towards an Architecture” (1923), or more specifically, his very particular reading of the revolutionary text.This way he builds the first functionalist house in Mexico in 1929, followed by a series of schools characterized by nudity and frugality unparalleled even in the same Le Corbusier-like proposal. Subsequently, and thanks to his relations with the national revolutionary intelligentsia, he put into practice his functionalist proposal in the construction of some private houses, among which are those made for the painters Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in 1932. However after this Funcionalist effervescence of the thirties O’Gorman completely disconnects from the architectural discipline to devote himself to his passion for mural painting. In the late 1940s he began to explore new techniques in mural painting by introducing the use of polychrome mosaics made with stones extracted from different regions of the country.

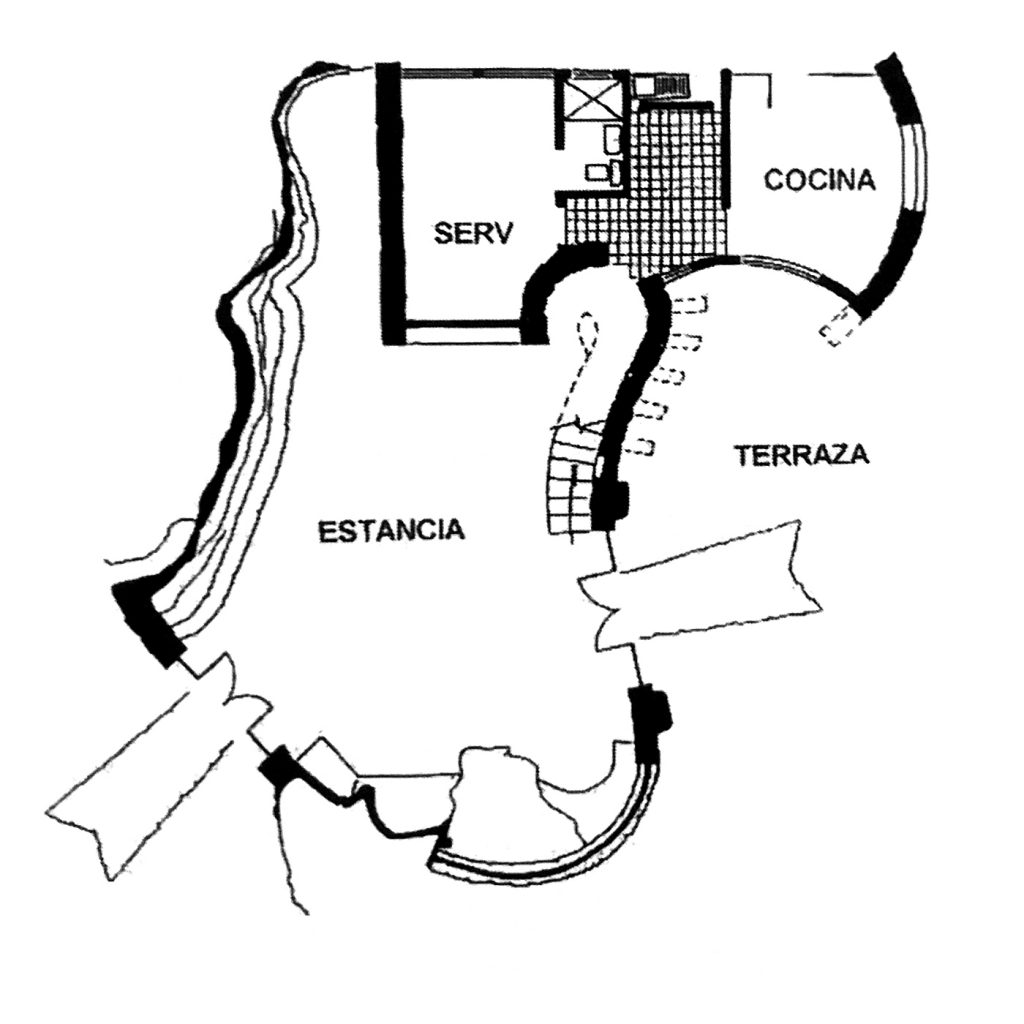

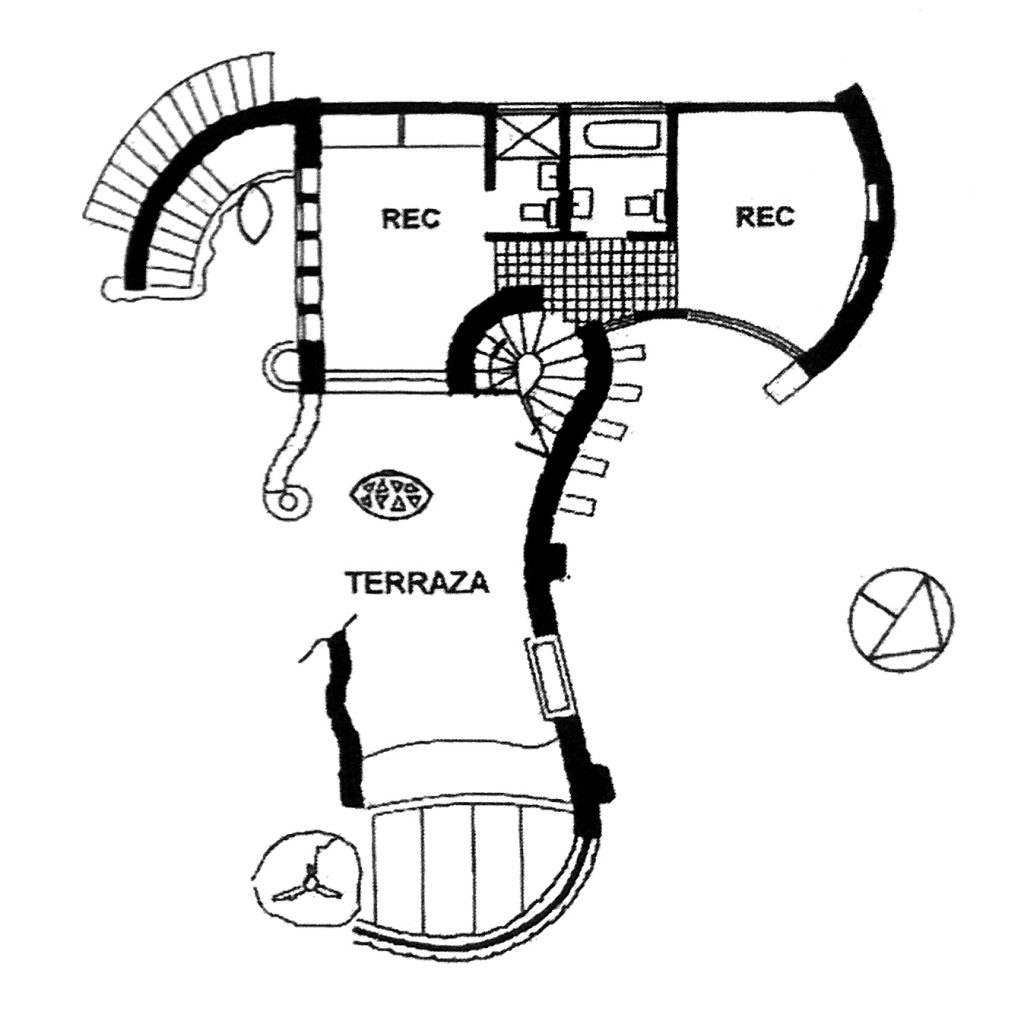

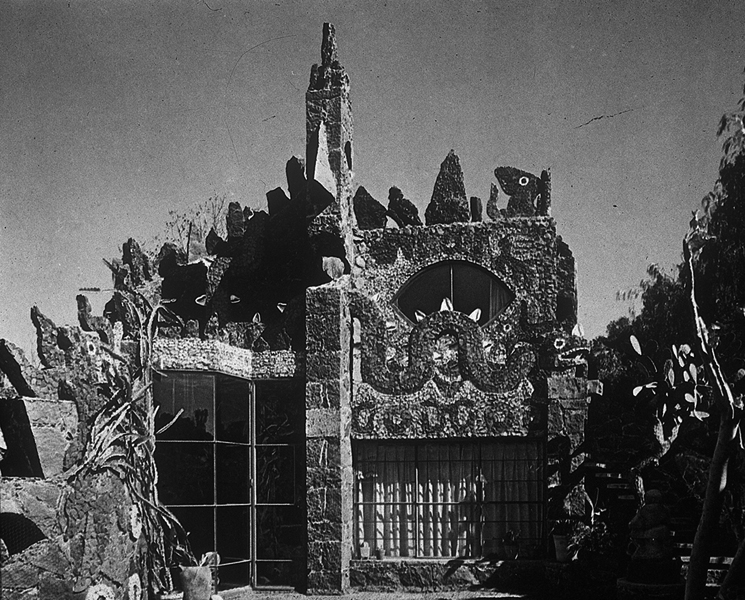

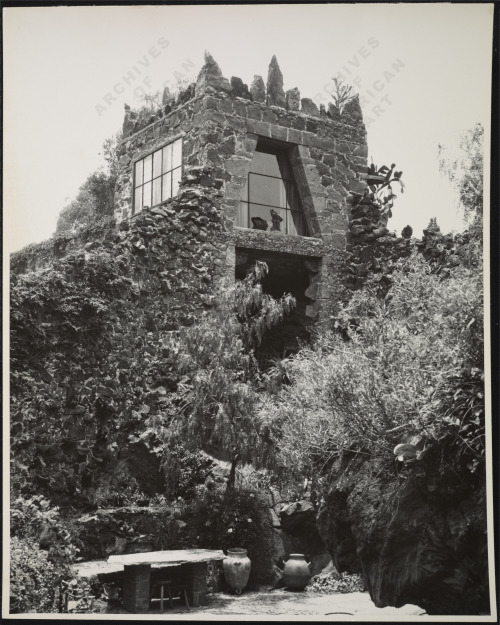

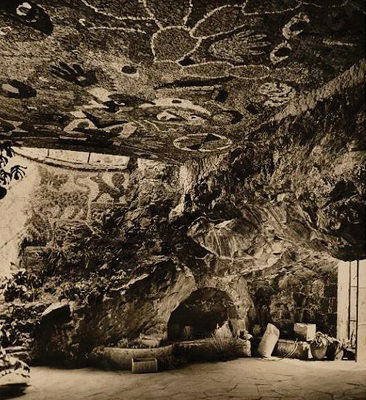

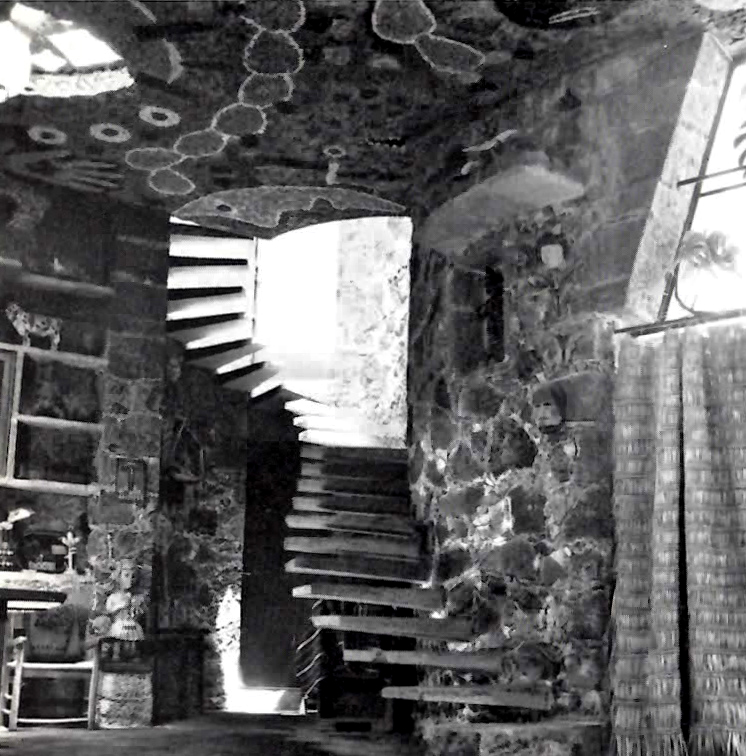

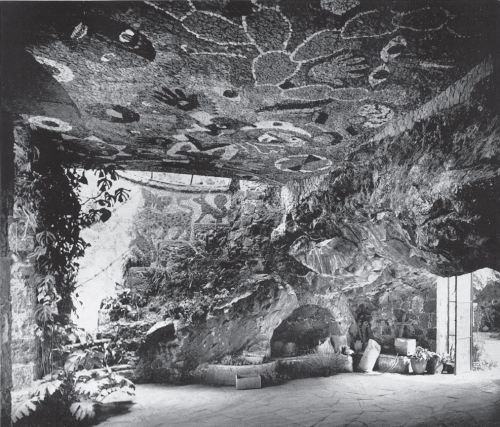

Pero no fue hasta entrada la década de 1950 que el Realismo tan promovido y defendido como verdadera identidad nacional por Rivera y O’ Gorman se hubiera visto materializado en la arquitectura. En un terreno propiedad de Juan O’ Gorman que se encontraba en el tan afamado barrio del Pedregal en el sur de la ciudad de México, el arquitecto construye su propia casa. O’Gorman, evadiendo cualquier generalización, intenta particularizar su propuesta, creando no sólo un vínculo, sino una verdadera fusión con el lugar, o más aún, una emersión de la misma tierra. El resultado fue prácticamente una cueva casi natural que recordaba a algunas construcciones italianas manieristas del siglo XVI; incluso en la misma definición del espacio más importante de la construcción, es decir la sala, se guardaba una relación formal con esta arquitectura antiacademicista; su formal oval resultaba una evocación de las salas de las grutas construidas en los jardines de Boboli en Florencia por Il Tribolo cuatro siglos antes.

But it was not until the early 1950s that Realism so promoted and defended as a true national identity by Rivera and O ‘Gorman would have been materialized in architecture. On a piece of land owned by Juan O ‘Gorman in the famous neighborhood of Pedregal in the south of Mexico DF, the architect builds his own house. O’Gorman, avoiding any generalization, tries to particularise his proposal, creating not only a link, but a true fusion with the place, or even more, an emersion of the same land. The result was practically an almost natural cave that remembered some mannerist Italian constructions of century XVI; even in the very definition of the most important space of the construction, that is to say the room, was kept a formal relationship with this antiacademicist architecture ; Its formal oval was an evocation of the rooms of the caves built in the gardens of Boboli in Florence by Il Tribolo four centuries before.

Ya sea por la misma forma sugerente de la casa, como por la serie de jardines que lo circundaban, la casa lograba hacerse uno con el paisaje; no restándole sin embargo sorpresa al visitante al momento de encontrársela por primera vez, en una especie de objet trouvé surrealista. La elección de la cueva como modelo para la definición de la casa puede tener distintas lecturas que más que contraponerse se complementan; por un lado el arquetipo de la cueva recordaba los mismos orígenes de la arquitectura, una forma casi inconsciente de volver a la esencia de habitar, es decir, refugiarse. Por otro lado, la cueva evocaba directa o indirectamente el vientre materno, una idea ligada en cierta forma al pensamiento surrealista.

Either by the same suggestive form of the house, or by the series of gardens that surrounded it, the house managed to become one with the landscape; not withstanding the surprise to the visitor when it was first encountered, in a kind of surrealistic objet trouvé. The choice of the cave as a model for the definition of the house can have different readings that more than contrast are complemented; On the one hand the archetype of the cave recalled the same origins of architecture, an almost unconscious form of returning to the essence of dwelling, that is, to take shelter. On the other hand, the cave evoked directly or indirectly the maternal womb, an idea linked in some way to surrealist thinking.

Text by Luis Villarreal Ugarte