“The passage of the centuries through the city has in many cases left singular testimonies, both spatial: squares, streets, promenades, gardens, etc., and architectural: churches, palaces, monuments that it would be a stupid crime to destroy. Faced with a monumental city, the urbanistic dilemma has arisen of stratifying it, stopping it, dissecting it, to be presented as a museum object, or else to go more or less slowly, incorporating it into present-day life, with the danger, of course, of actually destroying its archaeological values. I sincerely believe that both of these attitudes are wrong, and the only correct way to seriously tackle the urban planning problem of a monumental city is to study and bravely establish a hierarchy of its constituent factors and then arrange them according to that hierarchy. Of course, this study and hierarchy of factors is always a subjective task of judgement and also a subjective work of criteria and also of the sensibility of the town planner. The static problems of these adjustments of the old city require a museographic treatment of the most exquisite sensitivity and their coexistence settings require an exceptionally cultured civic education. All of which does not suggest very optimistic prospects for our monumental cities. And I would like to warn that, as painful as the loss of the monumental values of our cities due to neglect and abandonment is, I fear even more the restorations and refurbishments, carried out with clumsy archaeological and town planning criteria.”

“El paso de los siglos por la ciudad ha dejado en muchos casos testimonios singulares, tanto espaciales: plazas, calles, paseos, jardines, etc., como arquitectónicos: iglesias, palacios, monumentos que sería un estúpido crimen destruir. Ante una ciudad monumental se plantea el dilema urbanístico de estratificarla, detenerla, disecarla, para presentarla como objeto de museo, o bien ir más o menos despacio, incorporándola a la vida actual, con el peligro, claro está, de destruir realmente sus valores arqueológicos. Creo sinceramente que ambas actitudes son erróneas, y que la única forma correcta de abordar con seriedad el problema urbanístico de una ciudad monumental es estudiar y jerarquizar con valentía los factores que la componen y ordenarlos según esa jerarquía. Por supuesto, este estudio y jerarquización de los factores es siempre una tarea subjetiva de juicio y también un trabajo subjetivo de criterio y también de sensibilidad del urbanista. Los problemas estáticos de estas adecuaciones de la ciudad antigua requieren un tratamiento museográfico de la más exquisita sensibilidad y sus escenarios de convivencia requieren una educación cívica excepcionalmente culta. Todo lo cual no sugiere perspectivas muy optimistas para nuestras ciudades monumentales. Y quiero advertir que, por muy dolorosa que sea la pérdida de los valores monumentales de nuestras ciudades por la desidia y el abandono, temo aún más las restauraciones y remodelaciones, realizadas con torpes criterios arqueológicos y urbanísticos.”

Miguel Fisac, La molécula Urbana

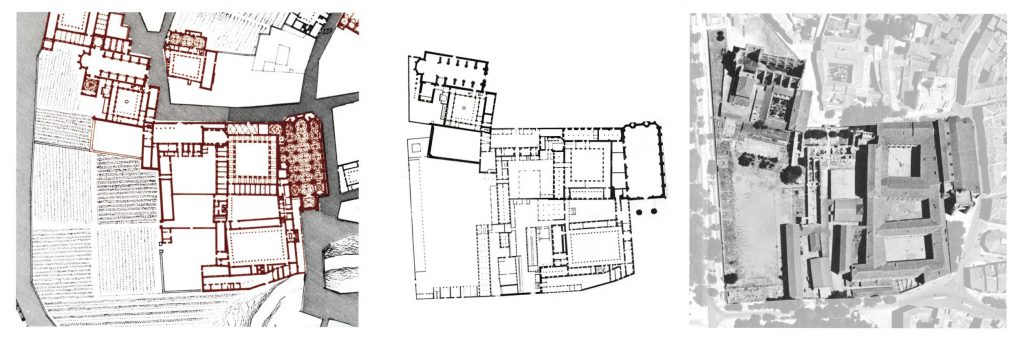

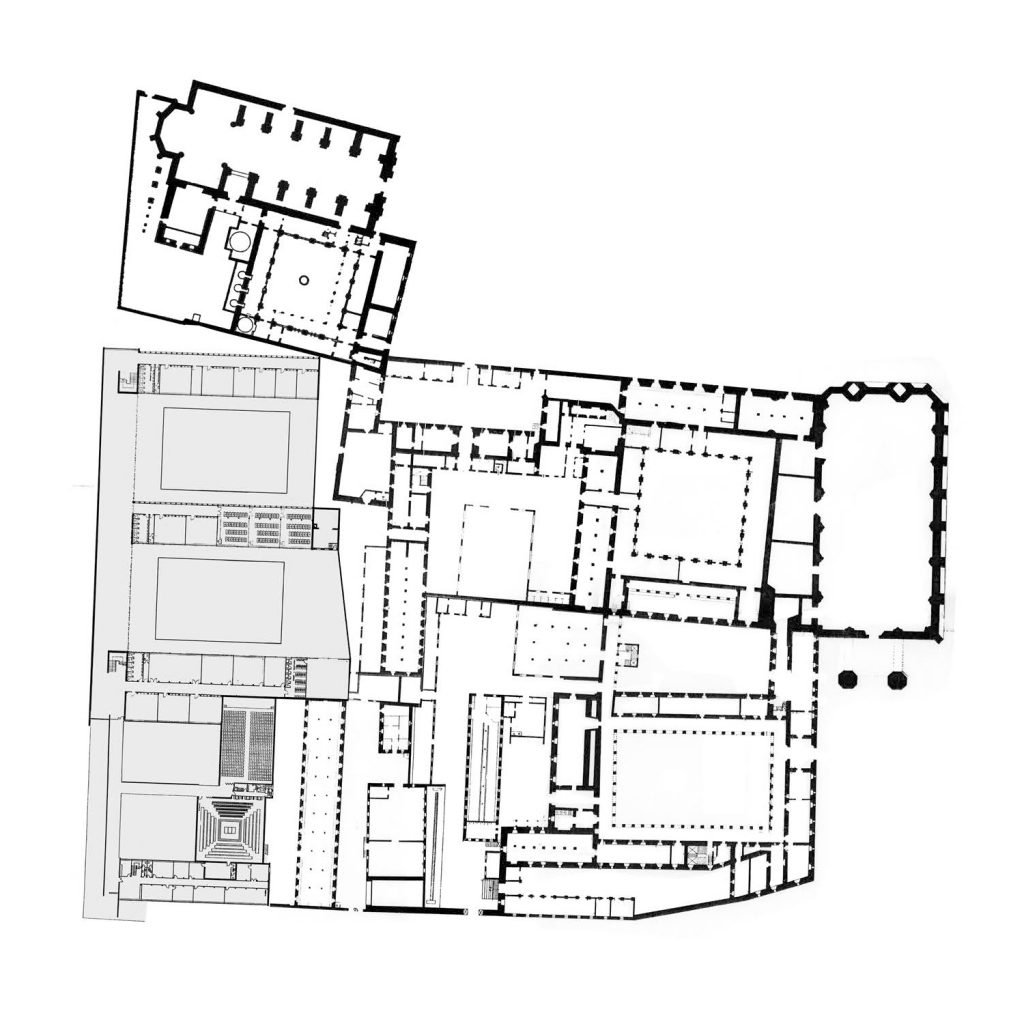

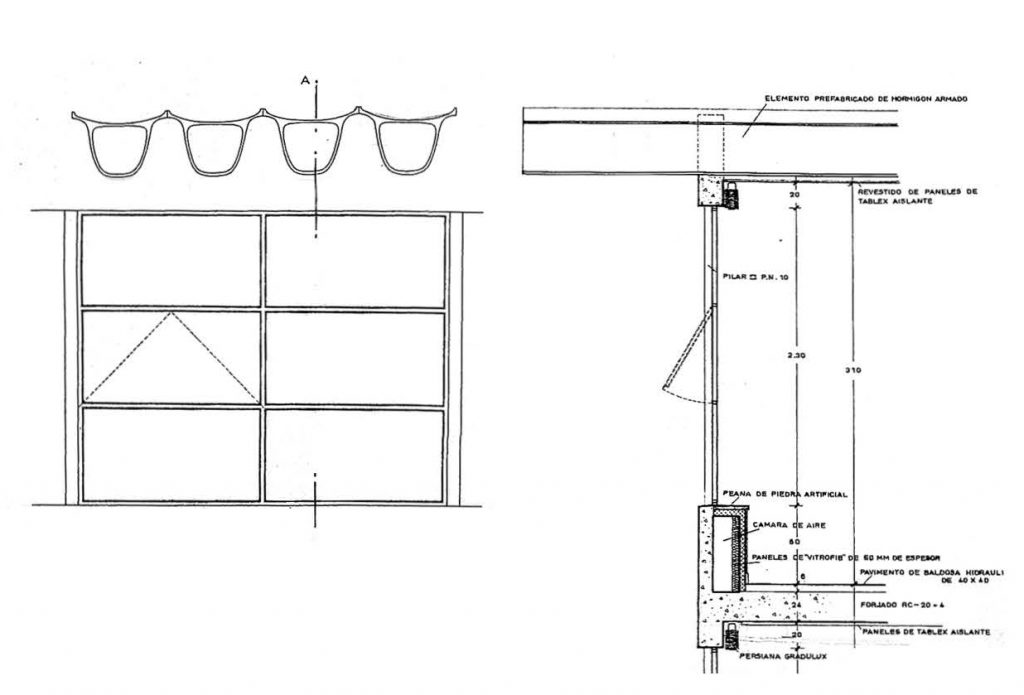

Miguel Fisac’s interest in designing the building in relation to its urban surroundings, taking into account and depending on the classicist tradition of the city. A statement that is undoubtedly difficult to understand in the isolated urban state in which it is currently located. The situation of the monastic macro-block of San Benito and San Agustin, disentailed in 1837, is shown in these plans which we have graphically joined together, showing the state of the then barracks in 1933. This was a state in which the universal traces given in 1582 by the classicist architect Juan de Ribero Rada had been respected, similar to the urban situation dated 1738. The circumstances in which Fisac found the intervention site, shown in the aerial photograph of the time, where only the buildings attached to the west and south walls of the barracks disappeared after the war.

El interés de Miguel Fisac por diseñar el edificio en relación con su entorno urbano, teniendo en cuenta y dependiendo de la tradición clasicista de la ciudad. Una afirmación que sin duda es difícil de entender en el estado urbano aislado en el que se encuentra actualmente. La situación de la macromanzana monástica de San Benito y San Agustín, desamortizada en 1837, se muestra en estos planos que hemos unido gráficamente, mostrando el estado del entonces cuartel en 1933. Un estado en el que se habían respetado las trazas universales dadas en 1582 por el arquitecto clasicista Juan de Ribero Rada, similar a la situación urbana fechada en 1738. Las circunstancias en las que Fisac encontró el lugar de la intervención, mostradas en la fotografía aérea de la época, en la que sólo desaparecieron los edificios adosados a los muros oeste y sur del cuartel después de la guerra.

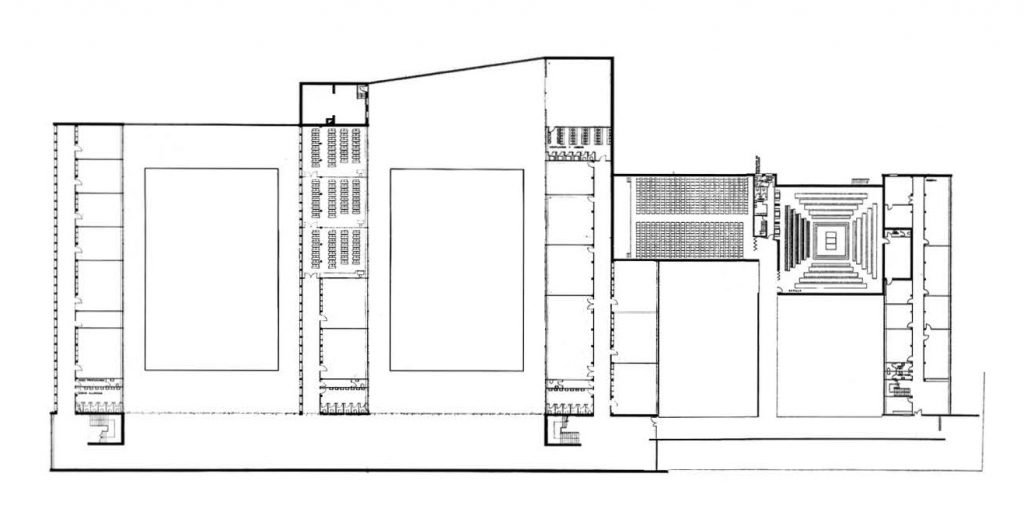

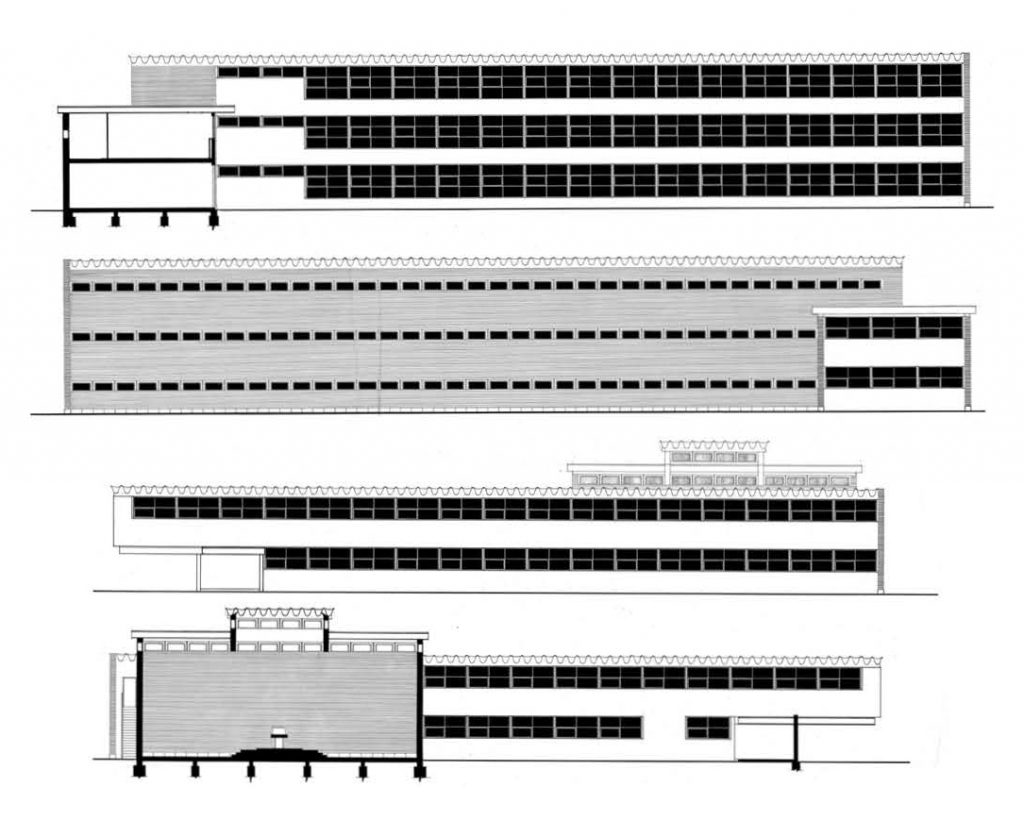

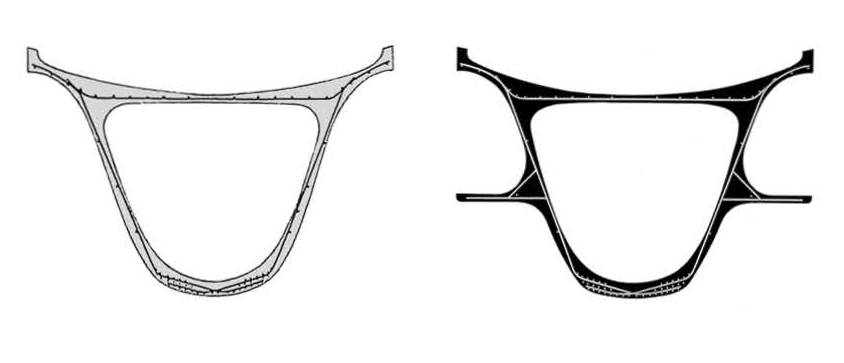

The project’s placement on the site maintains a double criterion. At the first level of analysis with the organisation of the floor plan in the area of the singular buildings: chapel, administration, access and assembly hall are arranged in the south-west corner along two small courtyards articulated by a broken canopy; an open corridor that was never built. Likewise, the area corresponding to the three classroom galleries is laid out in a comb with the best orientation of the plot, east-west; logically the same as that used by Ribero Rada in the dominant bays of his layout. However, although the classroom blocks appear with rigid functional features and apparently independent of the bays to the west of the monastery, they used their walls to enclose the comb. Thus, the open spaces between the classrooms are understood as courtyard-cloisters with proportions and formal relations between their parts similar to those existing between the classicist cloisters designed in the universal layout of 1582. All these data and their analysis together in their real situation, which has disappeared, inform us of Fisac’s guiding idea in this building: he followed the formal structure of Ribero Rada’s design as the inspiration for his project and also used the whole of his building in a difficult timeless dialogue to close – formally sewing its parts to the adjoining parts of the monastery – one of the most complex blocks of the monumental city of Valladolid. complex blocks of the monumental city of Valladolid. We now understand Miguel Fisac’s explanation of how he had designed the general plan in such a way as to the general floor plan in such a way that several of the bays of the Institute rested on the walls of the The building was designed in such a way that several of the bays of the Institute would rest on the walls of the then Regiment of the Artillery Regiment.

El emplazamiento del proyecto en el solar mantiene un doble criterio. En un primer nivel de análisis con la organización de la planta en la zona de los edificios singulares: capilla, administración, acceso y salón de actos se disponen en la esquina suroeste a lo largo de dos pequeños patios articulados por una marquesina quebrada; un pasillo abierto que no llegó a construirse. Asimismo, la zona correspondiente a las tres galerías de aulas se dispone en peine con la mejor orientación de la parcela, este-oeste; lógicamente la misma que utilizó Ribero Rada en las crujías dominantes de su trazado. Sin embargo, aunque los bloques de aulas aparecen con características funcionales rígidas y aparentemente independientes de las crujías al oeste del monasterio, utilizaron sus muros para cerrar el peine. Así, los espacios abiertos entre las aulas se entienden como patios-claustro con proporciones y relaciones formales entre sus partes similares a las existentes entre los claustros clasicistas diseñados en la traza universal de 1582. Todos estos datos y su análisis conjunto en su situación real, ya desaparecida, nos informan de la idea rectora de Fisac en este edificio: siguió la estructura formal del diseño de Ribero Rada como inspiración de su proyecto y además utilizó el conjunto de su edificio en un difícil diálogo atemporal para cerrar -cosiendo formalmente sus partes a las partes contiguas del monasterio- una de las manzanas más complejas de la ciudad monumental de Valladolid. complejas de la ciudad monumental de Valladolid. Entendemos ahora la explicación de Miguel Fisac de cómo había diseñado la planta general de tal manera que varias de las crujías del Instituto descansaran sobre los muros del El edificio fue diseñado de tal manera que varias de las crujías del Instituto descansaran sobre los muros del entonces Regimiento de Artillería.

Text by Daniel Villalobos