There is always some confusion in defining what Manhattanism is and, mainly, how it is shown in a single building that represents the congestion of the island, its verticality, overlapping uses, etc. If we think of Manhattan and its skyscrapers, the Empire Estate, the Chrysler Building, or the Rockefeller Center come to mind, projects that define the city’s skyline but which today are impenetrable. They appear to us as the infinite vertical repetition of the office plan. His epic is more symbolic than real. In Delirious New York, Rem Koolhaas introduced us to the Downtown Athletic Club as a building representing said Manhattanism. The architect himself defines it as “the complete conquest of the skyscraper, floor by floor, by social activity,” and how the skyscraper is used as a constructivist “social condenser”: a machine to generate and intensify some modalities of relationships with human.” In Delirious New York, the Downtown Athletic Club is shown to us in a section where the height of the slabs changes to house different hedonistic conditions, each one more extravagant than the last: a swimming pool, a golf course, oysters, etc. However, the Downtown Athletic Club was still an inaccessible private club: another opaque skyscraper on the Manhattan skyline.

Siempre aparece una cierta confusión en definir que es el Manhattanismo y, principalmente, como se muestra en un único edificio que defina la congestión de la isla, su verticalidad, superposición de usos, etc. Si pensamos en Manhattan y sus rascacielos, nos viene a la mente el Empire Estate, el Chrysler Building o el Rockefeller Center, proyectos que definen el skyline de la ciudad, pero que hoy en día son impenetrables. Se nos presentan como la repetición en vertical infinita de la planta de oficinas. Su épica es más simbólica que real. Rem Koolhaas en Delirio de Nueva York, nos presentó el Downtown Athletic Club como un edificio que representaba dicho Manhattanismo. El propio arquitecto lo define como “la conquista completa del rascacielos, planta a planta, por parte de la actividad social,” y como el rascacielos se usa como un “condensador social” constructivista: una máquina para generar e intensificar algunas modalidades de las relaciones humanas”. En Delirio de Nueva York, el Downtown Athletic Club se nos muestra en sección donde la altura de los forjados va cambiando para albergar distintas condiciones hedonistas, cada una de ellas más extravagante que la anterior: una piscina, un campo de golf, un bar de ostras, etc. Sin embargo, el Downtown Athletic Club no dejaba de ser un club privado inaccesible: otro rascacielos opaco en el skyline de Manhattan.

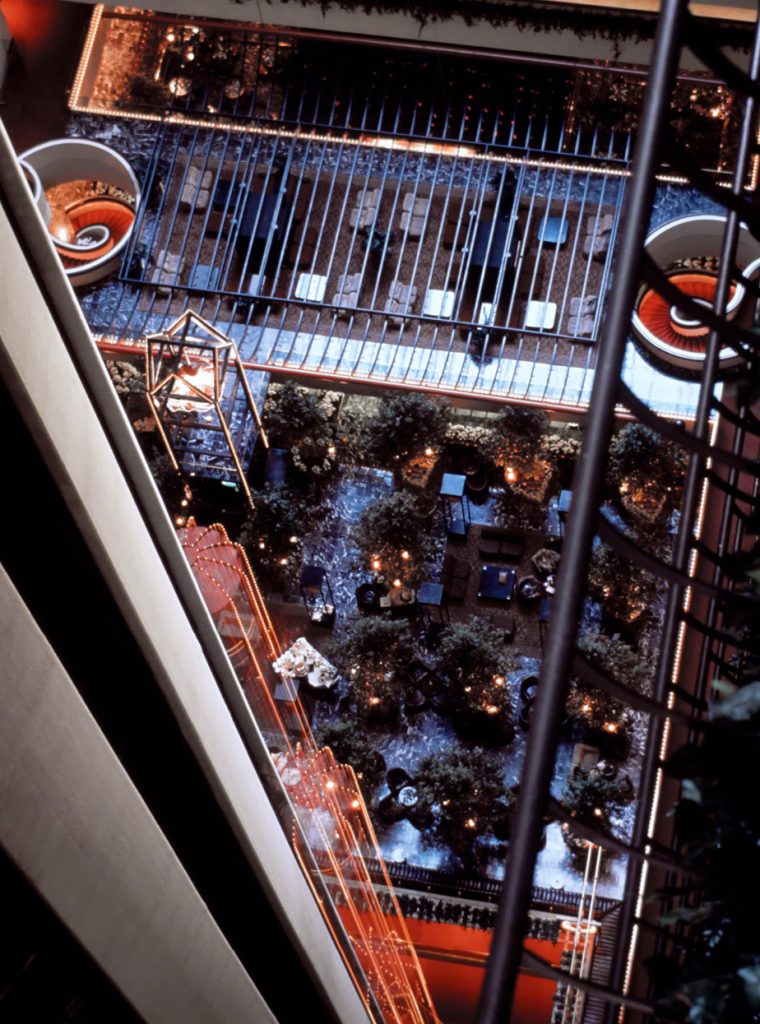

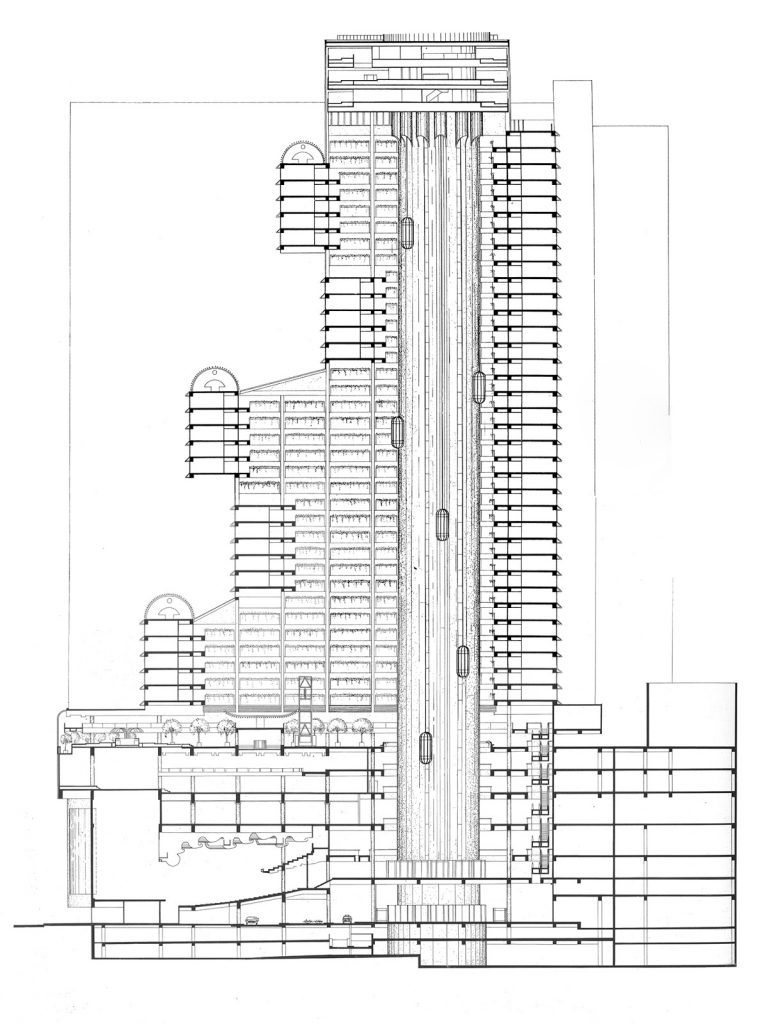

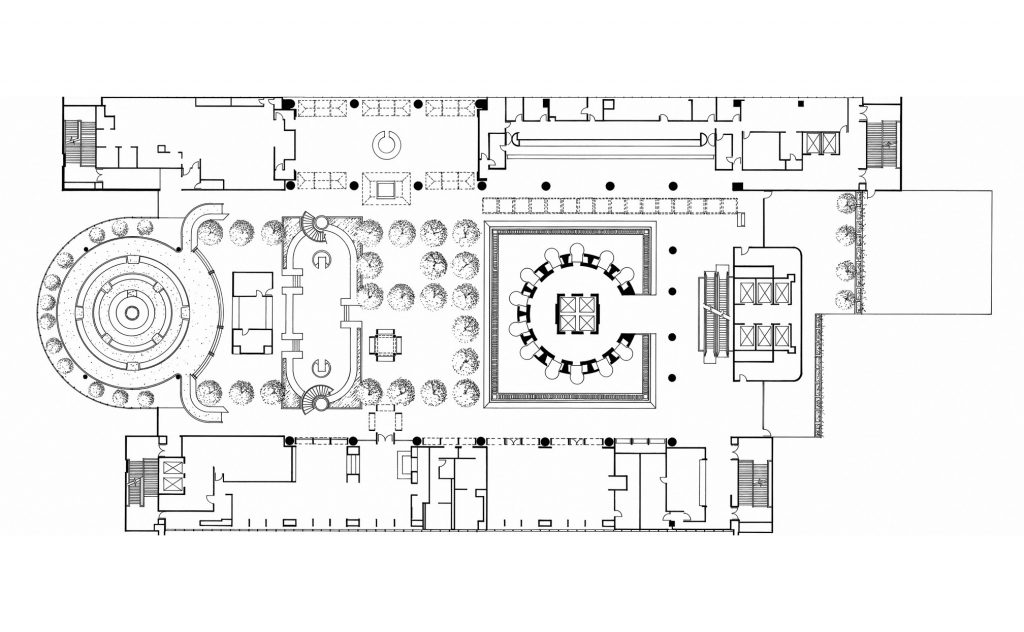

There is another project, much less known even to those who live in the city, that comes much closer to this idea of Manhattanism. The skyscraper becomes a condenser of overlapping commercial activities and residences. This building is the Marriot Marquis Hotel in Times Square. Located on a privileged lot between 45th and 46th streets with its east façade open to Times Square, the Marriot Marquis Hotel is a vertical continuation of the congestion created around this mythical urban node, half tourist, half infrastructure hub. The main program of the building is a hotel, but it is complemented by other recreational uses such as bars, restaurants, shops, or a theater with 1,600 seats. The John Portman building is built using two large parallel bars, finished in concrete, located at the north and south ends of the site and which house the rooms. In between, a series of volumes set back on the edge of the plot facing Times Square connects both bars and create a central atrium that runs practically the entire building height. These volumes house various public facilities of the hotel, such as gyms, lobbies, bars, promenades, etc. In the center of this great atrium, a circular nucleus of elevators distributes the public circulation of the hotel to all its floors.

Hay otro proyecto, mucho menos conocido incluso para aquellos que residen en la ciudad que se acerca bastante más a esta idea de Manhattanismo. El rascacielos se convierte en un condensador de actividades comerciales y residencias superpuestas. Este edificio es el Hotel Marriot Marquis de Times Square. Localizado en un solar privilegiado entre las calles 45 y 46 con su fachada este abierta a Times Square, el Hotel Marriot Marquis es una continuación en vertical de la congestión creada en torno a este mítico nodo urbano, mitad turístico, mitad nudo infraestructural. El programa principal del edificio es un hotel, pero se complementa con otros usos lúdicos tales como bares, restaurantes, tiendas o un teatro con 1600 asientos. El edificio de John Portman se construye mediante dos grandes barras paralelas, acabadas en hormigón, que se localizan en los extremos norte y sur del solar y que albergan las habitaciones. Entre medias, una serie de volúmenes retranqueados sobre límite de la parcela que da a Times Square conectan ambas barras y crean un atrio central que recorre prácticamente toda la altura del edificio. Estos volúmenes albergan varios equipamientos públicos del hotel tales como gimnasios, lobbies, bares, promenades, etc. En el centro de este gran atrio, un núcleo circular de ascensores distribuye la circulación pública del hotel a todas sus plantas.

This is where some conceptual and formal similarities and differences between the Portman Hotel and the Manhattanism proposed by Koolhaas are established. Unlike the Downtown Athletic Club or other New York skyscrapers, the Marriot Marquis Hotel envelope is not insulated from what goes on behind its walls. The interior and exterior feed off each other without falling into the hackneyed mantra that form follows function. On the contrary, the exterior spatial and formal conditions are forced to generate a succession of events that surprise and dazzle the visitor. Following this idea, the location of the central elevators, which one can be seen while ascending through the central atrium, is another of the main differences with the Downtown Athletic Club. In this project, the access to the building and the ascent was an almost clandestine act. Returning to the New York Delirium book, Koolhaas describes the experience as follows: “Upon exiting the elevator on the 9th floor, the visitor finds himself in a dark hallway that leads directly to a changing room located in the center of the platform where no there is natural light.” This way of understanding access to a venue is a typical New York condition, and it is valued almost as part of the urban experience.

Aquí es donde se establecen algunas de las similitudes y diferencias conceptuales y formales del hotel de Portman con el Manhattanismo propuesto por Koolhaas. A diferencia del Downtown Athletic Club u otros rascacielos neoyorquinos, la envolvente del hotel Marriot Marquis no está aislada respecto a lo que ocurre en detrás de sus muros. El interior y exterior se retroalimentan sin caer en el manido mantra de que la forma sigue a la función. Al contrario, se fuerzan las condiciones espaciales y formales exteriores para generar una sucesión de acontecimientos que sorprendan y deslumbren al visitante. Siguiendo esta idea, la localización de los ascensores centrales en las que uno se deja ver mientras asciende a través del atrio central es otra de las diferenciaciones principales con el Downtown Athletic Club. En este proyecto, el acceso al edificio y la ascensión era un acto casi clandestino. Volviendo al libro de Delirio de Nueva York, Koolhaas describe la experiencia de la siguiente manera “Al salir del ascensor en la planta 9ª, el visitante se encuentra en un vestíbulo oscuro que lleva directamente a un vestuario situado en el centro de la plataforma donde no hay luz natural.” Esta manera de entender el acceso a un local es una condición típica de Nueva York, y que se valora casi como parte de la experiencia urbana.

In the case of the Marriot Marquis Hotel, the experience is bombastic and cinematic from the first moment and reaches its splendor in the atrium and elevators. The reasons for this paradigm shift could be several: First, John Portman was never a New York architect (he lived his entire life in Georgia), so his references were never in Manhattan; Second, the hotel was part of a broader line of research within his work regarding this typology and the way to build atriums as circulatory elements; Finally, when the project was built in the 1980s, the Times Square area was heavily degraded, so to make the hotel work economically, an open and safe character was required. On the contrary, it is possible that these same reasons, added to the fact that John Portman was not only an architect but also a developer, have meant that the hotel has been erased from the architectural imaginary of the city.

En el caso del hotel Marriot Marquis, la experiencia es grandilocuente y cinematográfica desde el primer momento y llega a su esplendor en el atrio y sus ascensores. Las razones de este cambio de paradigma pueden ser varias: Primero, John Portman nunca fue un arquitecto neoyorquino (vivió toda su vida en Georgia) por lo que sus referencias nunca estuvieron en Manhattan; Segundo, el hotel fue parte de una línea de investigación más amplia dentro de su trabajo en cuanto a esta tipología y la manera de construir atrios como elementos circulatorios; Finalmente, cuando el proyecto fue construido en los años 80, la zona de Times Square estaba fuertemente degradada, por lo que para conseguir que el hotel funcionara económicamente, se requería que tuviera un carácter abierto y seguro. Por el contrario, es posible que estas mismas razones, sumadas al hecho de que John Portman fuera no solo arquitecto sino también promotor, hayan hecho que el hotel haya sido borrado del imaginario arquitectónico de la ciudad.

***

Currently (originally written in May 2016 and revised in 2019), the hotel can be visited almost in its entirety, without any restrictions, maintaining the open character described above. The entrance to the building is through 45th and 46th streets, which connects with a large arrival area for cars and pedestrians. From here you can access both the hotel and the rest of the facilities. The first six floors are occupied by a congress area and various clothing stores; a series of escalators allow us to ascend to the seventh floor where the great vertical atrium and the hotel’s own cinematographic experience begin. This floor houses the hotel reception and a large cafeteria-restaurant that extends from the elevator core to the east façade, from where you can see Times Square in its entirety (practically the only building that is not covered by advertising screens). If we look up we see how the immense atrium of more than 30 floors contracts to the rhythm of the volumes that close it on the east façade. Hanging plants used to fall from the railings that close the corridors to the rooms, but nowadays they are closed with latticework. We take one of the elevators that will allow us to see the atrium in all its splendor and that will take us to the top floor of the hotel: a circular and rotating restaurant with views of the neighboring skyscrapers of Times Square, an interrupted view of the city’s skyline by the recent constructions that exceed the height of the hotel itself. This restaurant is the latest attraction in a building that purports to be spectacle while at the same time embracing and rejecting Manhattan’s skyscraper culture.

En la actualidad (escrito originalmente en mayo de 2016 y revisado en 2019), el hotel puede ser visitado casi en su totalidad, sin ninguna restricción, manteniendo el carácter abierto descrito anteriormente. La entrada al edificio se realiza través de las calles 45 y 46 que conecta con una gran zona de llegada para coches y peatones. Desde aquí se accede tanto al hotel como al resto de equipamientos. Las primeras seis plantas están ocupadas por una zona de congresos y varias tiendas de ropa; una serie de escaleras mecánicas nos permiten ascender hasta el séptimo piso donde comienza el gran atrio vertical y la propia experiencia cinematográfica del hotel. Esta planta alberga la recepción del hotel y una gran cafetería-restaurante que se extiende desde núcleo de los ascensores hasta la fachada este, desde donde se puede ver Times Square en su totalidad (prácticamente el único edificio que no está cubierto por pantallas publicitarias). Si miramos hacia arriba vemos como el inmenso atrio de más de 30 plantas se contrae al ritmo de los volúmenes que lo cierran por la fachada este. De las barandillas que cierran los pasillos a las habitaciones solían caer plantas colgantes, pero en la actualidad están cerradas con celosías. Tomamos uno de los ascensores que nos permitirá ver el atrio en todo su esplendor y que nos llevarán a la última planta del hotel: un restaurante circular y rotatorio con vistas a los rascacielos colindantes de Times Square, una vista interrumpida del skyline de la ciudad por las recientes construcciones que superan la altura del propio hotel. Este restaurante es la última atracción de un edificio que pretende ser espectáculo, mientras que al mismo tiempo abraza y rechaza la cultura del rascacielos de Manhattan.

Cover image by Hidden Architecture.