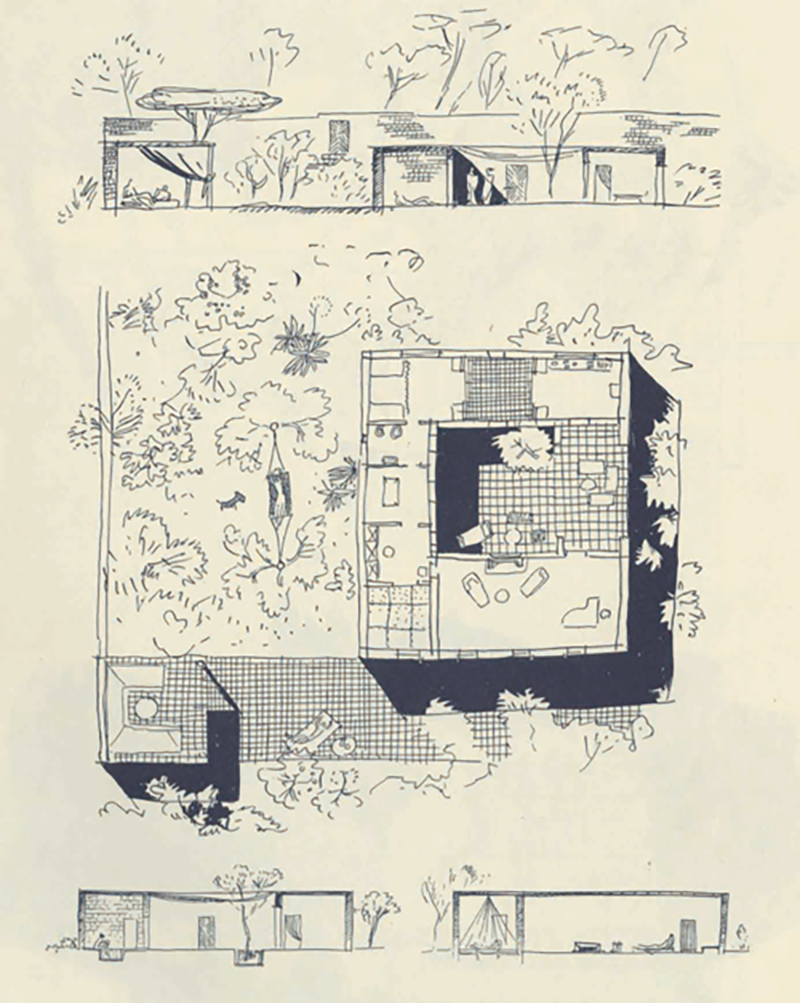

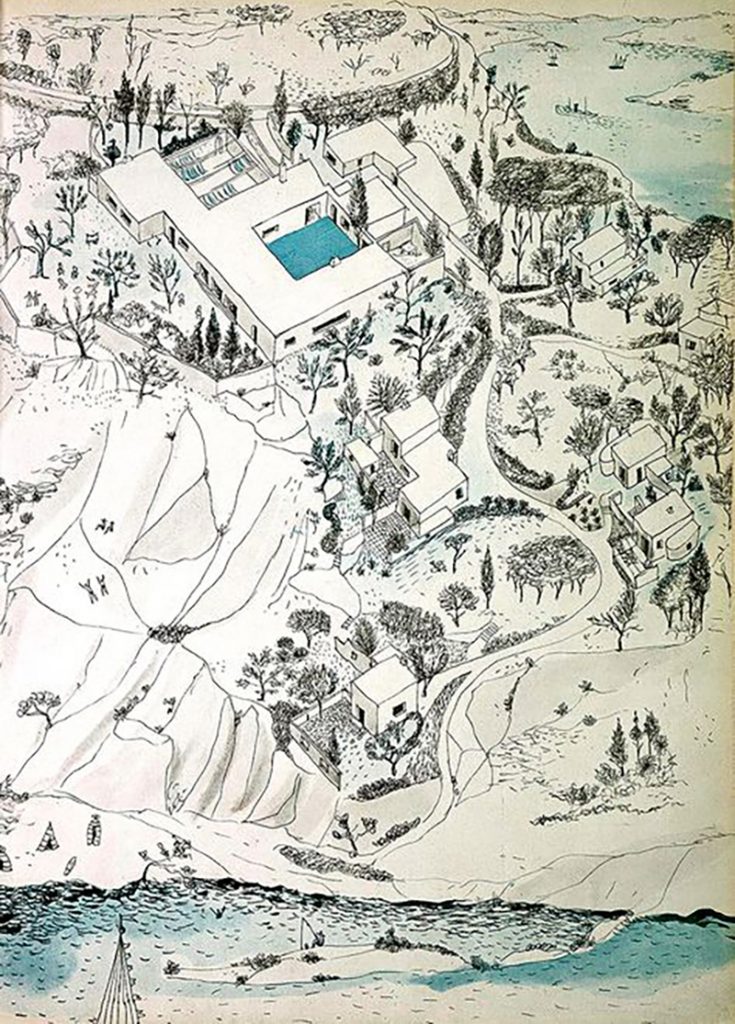

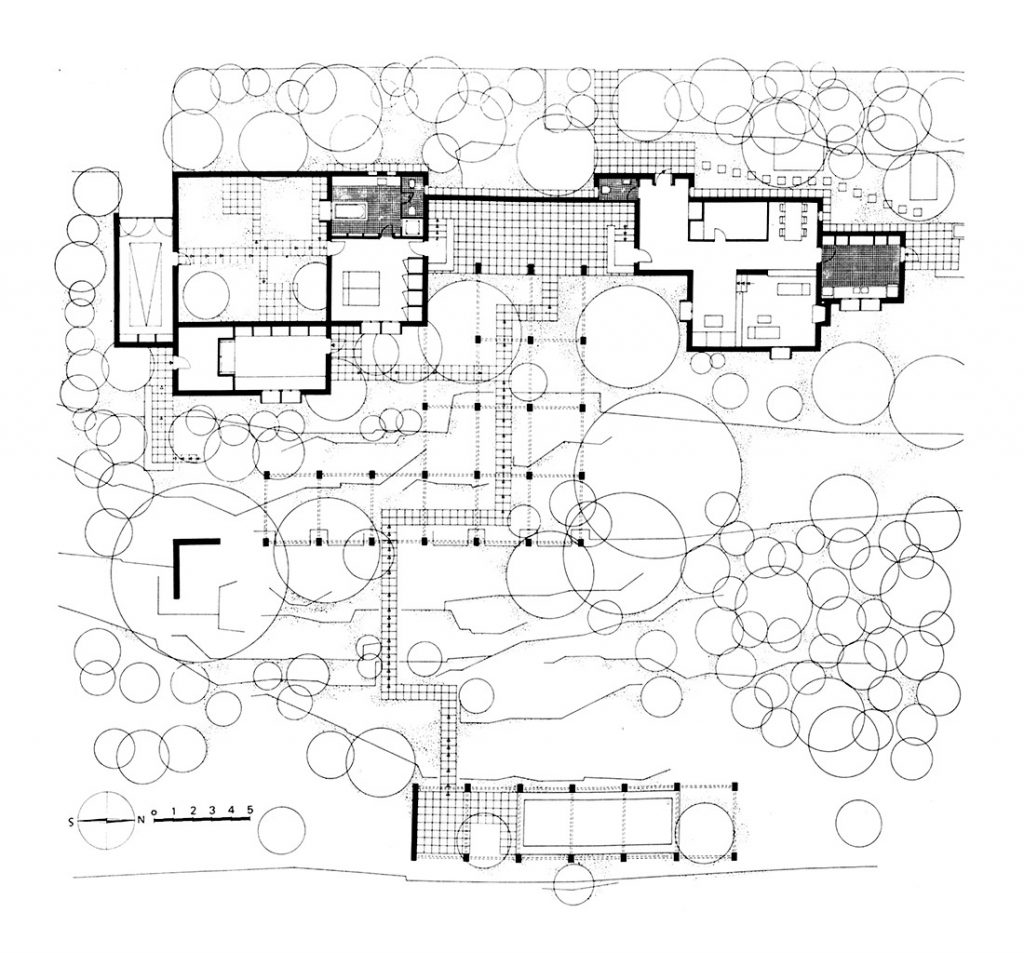

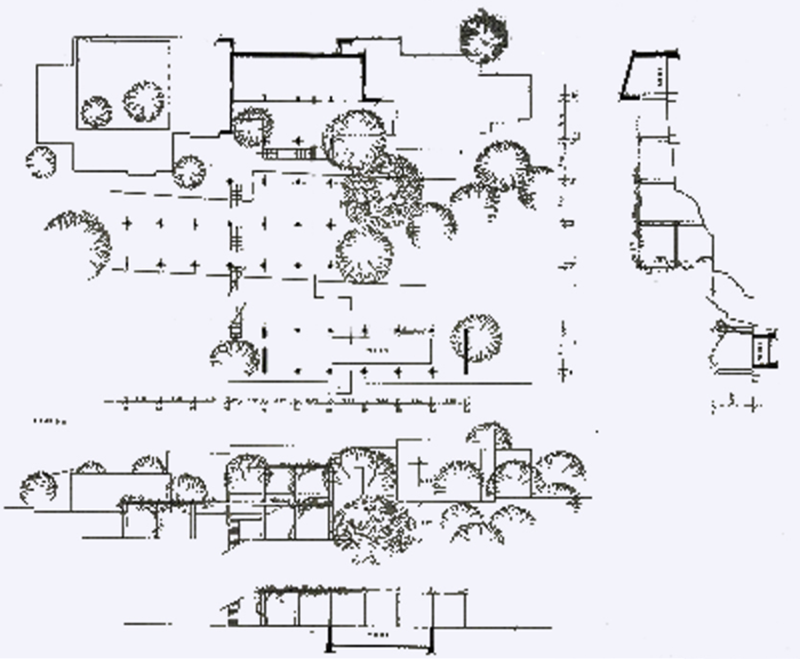

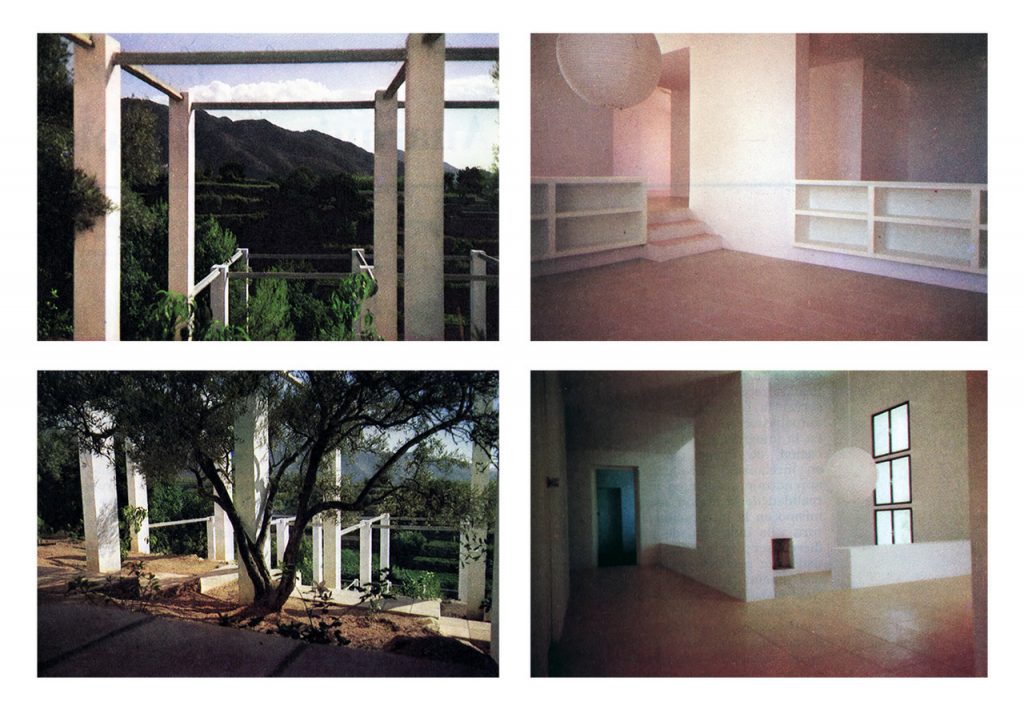

“La Casa” or “La Parra” is situated in the highest part of the plot and descends (from west to east) in terraces, adapting topographically to the terrain and taking advantage of both the vegetation of it (olive, fig and pine trees) and the steep slope in its development, a characteristic formalisation of the dwellings on the Mediterranean coast, and more specifically in Malaga. The rectangle of the ground plan generates its largest side from north to south with a length of more than 80 metres and a depth of 50 metres on a single storey, which brings together the minimum programme (bedroom, living room, kitchen, dining room and study) in two individualised volumes but linked together thanks to a transitional and unifying element: the portico from which the pergolas are generated which, through their routes, unify the natural elements dispersed throughout the estate and allow the enjoyment of the views of the sea and the vegetation to the lowest area of the property, where the swimming pool is located.

“La Casa” o “La Parra”, se sitúa en la zona más alta de la finca y desciende (de Oeste a Este) en terrazas, adaptándose topográficamente a la parcela, y aprovechando tanto la vegetación del terreno (olivos, higueras y pinos) como el abrupto desnivel en su desarrollo, formalización característica de las viviendas en la costa mediterránea, y más concretamente en Málaga. El rectángulo de la planta genera su lado mayor de norte a sur con un largo de más de 80 metros y unos 50 metros de fondo en una sola planta, que aglutinan el programa mínimo (dormitorio, estar, cocina, comedor y estudio) en dos volúmenes individualizados pero unidas entre sí gracias a un elemento de transición y unificador: el pórtico desde el que se generan las pérgolas que, mediante sus recorridos unifican los elementos naturales dispersos en la finca y permite el disfrute de las vistas al mar y de la vegetación hasta la zona más baja de la misma, donde se encuentra la piscina.

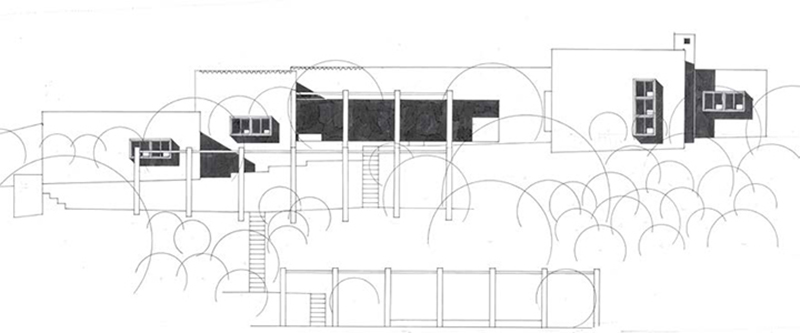

The main entrance to the house is located at the highest point of the plot (north façade), which is more closed and looks directly onto the road, while the main façade, to the south, opens onto the sea with fantastic views. From the secondary façade, the volume of the house is perceived as a continuous and closed whole, while the south façade is open and permeable, and allows us to distinguish the two main volumes that form it and are connected by a portico, and the pergolas in turn connect the five levels of the house, the garden and the swimming pool. But the portico is not only a backbone space for the living modules, but an expansion of the house, which the architect defined as a “Three dimensional frame for landscape”, for the enjoyment of the senses. The living areas of the home are divided into two separate modules linked by the portico: the daytime areas are on the north side, where the architect placed the dining room, kitchen and living room and the entrance to the home, while on the south side the main core is the inner courtyard, directly connected with the bedroom and its large bathroom; the garage and study (on a lower level) close off the other sides of the courtyard.

El acceso principal a la vivienda se encuentra en el punto más alto de la parcela, (fachada norte) de aspecto más cerrado y que mira directamente a la carretera, y de condición secundaria, mientras que la principal, al sur, se abre al mar con fantásticas vistas. Desde la fachada secundaria, el volumen de la vivienda se percibe como un todo continuo y cerrado, mientras que la fachada al sur es abierta y permeable, y nos permite distinguir los dos volúmenes principales que la conforman y se conectan mediante un pórtico, y las pérgolas a su vez, conectan los cinco niveles de la vivienda, el jardín y la piscina. Pero el pórtico no solo es un espacio vertebrador de los módulos de habitación, sino una expansión de la casa a la que el arquitecto definió como “Three dimensional frame for landscape” (un marco tridimensional del paisaje), para el disfrute de los sentidos. Las zonas de habitación de la vivienda se distribuye en dos módulos separados y unidos mediante el pórtico: los espacios para el día se encuentran en el lado norte, donde el arquitecto sitúa el comedor, la cocina y salón de estar y el acceso a la vivienda, mientras que en el lado sur el núcleo fundamental es el patio interior, conectado directamente con el dormitorio y su gran cuarto de baño; la cochera y el estudio (en un nivel inferior) cierran los otros lados del patio.

As the report for the BIC declaration of the building emphasises, “it is worth highlighting in this proposal the great architectural character with which the author has been able to qualify the plot without making any modification to its topography or vegetation conditions and also proposing a dwelling with a minimal, fragmented and open programme as opposed to the compact and large-scale models”. The project also “addresses functional aspects such as protection from the wind and direct sunlight, thanks to the vegetation, which is respected throughout the project. But the architect does not leave the conformation of the house and its walkways free: the grid of pillars and beams that support the house becomes the geometry that orders the terrain: respect for the landscape, the vegetation and the topography are the fundamental basis of the project, supported by the grid layout of the entire porch space, walkways and pergolas. Together with the design of the portico, the interior courtyard, with private access from the bedroom, is understood as another room in the house, a room limited by walls and without a roof, where one can sunbathe in the morning (to the east) or in the afternoon (to the west), a private area that reminds us of the sense of the Arabic courtyard in Andalusian culture, where the private area and the open-air space merge, two objectives sought by Rudofsky in his project.

Como ya destaca el informe para la declaración BIC del edificio, “es de destacar en esta propuesta el gran carácter arquitectónico con el que el autor ha sido capaz de cualificar la parcela sin realizar modificación alguna de sus condiciones de topografía o vegetación y planteando además una vivienda de programa mínimo, fragmento y abierto frente a los modelos compactos y de gran escala”. Así también, el proyecto “aborda aspectos funcionales como la protección de los vientos y de la luz solar directa, gracias a la vegetación, respetada en todo el proyecto. Pero el arquitecto no deja libre la conformación de la vivienda y sus paseos: la cuadrícula de pilares y vigas que sostienen la vivienda pasa a ser la geometría que ordena el terreno: el respeto al paisaje, la vegetación y la topografía son la base fundamental del proyecto, sustentado sobre la ordenación reticular de todo el espacio del pórtico, senderos y pérgolas. Junto al diseño del pórtico, el patio interior, de acceso privativo desde el dormitorio, se entiende como una habitación más de la casa, una habitación limitada por muros y sin techumbre, donde tomar baños de sol por la mañana (al este) o por la tarde (al oeste), zona privada que nos remite al sentido del patio árabe en la cultura andaluza, donde el área privada y el espacio al aire libre se fusionan, dos objetivos buscados por Rudofsky en su proyecto.

The design of the house-garden speaks of the architect’s design vision: respect for nature is combined with the grid of the pergolas and, as has been pointed out (BIC Declaration, 2011), this construction is not so much the result of manipulation of the terrain and its elements, but of the “contrasting convenience of order-bearing elements and natural support”. Thus the garden, an open space, like the courtyard, is also a container for the domestic programme, a programme studied for its personal and unique way of life, its own habits. From all this we can deduce the fundamental points of Rudofsky’s architectural thought: this house has been defined as a “manifesto and synthesis of proposals for contemporary living”, formalising the theories for living that Rudofsky developed throughout his life, the thought of a new way of inhabiting architecture. This thinking goes beyond simple architecture: respect for one’s own architectural forms (the vernacular) from a contemporary point of view, austerity and simplicity of means, inherited from popular wisdom, and respect for and wise use of the landscape (surroundings) and the topography of the land.

El diseño del jardín-casa (the house-garden) habla de la visión proyectual del arquitecto: el respeto a la naturaleza se une a la retícula de las pérgolas y, como se ha apuntado (Declaración BIC, 2011), esta construcción no viene tanto de la manipulación del terreno y de sus elementos, sino de la “conveniencia contrastada de elementos portadores de orden y el soporte natural”. Así el jardín, espacio abierto, como el patio, también es contenedor del programa doméstico, programa estudiado para su personal y única forma de vida, sus propios hábitos. De todo esto podemos deducir los puntos fundamentales del pensamiento arquitectónico de Rudofsky: esta casa se ha definido como “manifiesto y síntesis de las propuestas para el habitar contemporáneo”, formalizando las teorías para habitar que Rudofsky desarrolla durante toda su vida, el pensamiento de una nueva forma de habitar la arquitectura. Este pensamiento va más allá de la simple arquitectura: el respeto a las formas arquitectónicas propias (lo vernáculo) desde la mirada contemporánea, la austeridad y simplicidad de medios, heredada de la sabiduría popular, y el respeto y el uso sabio del paisaje (entorno) y de la topografía del terreno.

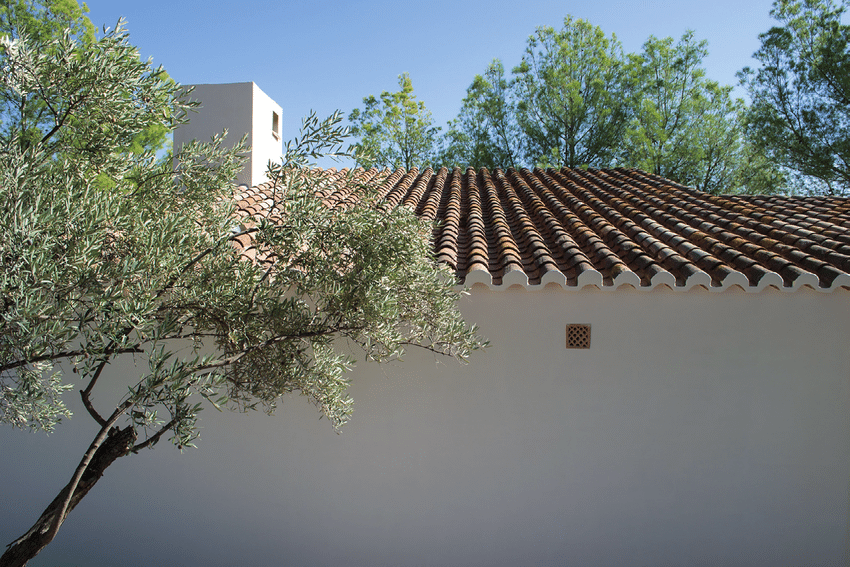

Berta and Bernard Rudofsky chose this plot of land in Frigiliana (ca. 1968) to build their summer house. Although the design is by Rudofsky, this project was to be signed by José Antonio Coderch de Sentmenat, as the former did not have his degree validated in Spain. A house designed to be enjoyed together with Berta: the architect starts with respect for the territory, both the plot and its surroundings, so his project is rooted in Mediterranean architecture and in the integration of plant elements (fig trees, olive trees, pines) and the shape of the land (slope), making use of current forms of construction, austerity as a way of life, and materials suited to the needs of the construction. There is no total disregard for technological advances: in the materials he makes some concessions to be taken into account; beyond the use of local materials (Arabic tiles, lime on the walls, earthen floors, white tiles, etc.), he uses reinforced concrete in the walls and the floors of the kitchen, pillars and slabs, replacing the traditional load-bearing walls. Besides, he uses metal carpentry in window frames, and frames the windows with ceramic material that flies over the openings, which, like a parasol, protects from the sun in summer (higher in the sky), and allows it to enter the house in winter, as it is lower in the sky.

Berta y Bernard Rudofsky eligen este terreno en Frigiliana (ca. 1968) para realizar su casa de verano. Aunque el diseño es de Rudofsky, este proyecto debe firmarlo José Antonio Coderch de Sentmenat dado que el primero no tiene convalidado el título en España. Una vivienda diseñada para el disfrute junto a Berta: el arquitecto parte del respeto al territorio, tanto de la parcela como de su entorno, por lo que su proyecto hunde sus raíces en la arquitectura mediterránea y en la integración de los elementos vegetales (higueras, olivos, pinos) como de la forma del terreno (inclinación), haciendo uso de las formas constructivas actuales, de la austeridad como forma de vida, y los materiales adecuados a las necesidades de la construcción. No hay un desprecio absoluto por los avances tecnológicos: en los materiales hace algunas concesiones a tener en cuenta; más allá del uso de materiales autóctonos (teja árabe, cal en las paredes, suelos de de tierra cocina, azulejos blancos, etc.), utiliza el hormigón armando en pilares y forjados, sustituyendo los muros de carga tradicional, utiliza la carpintería metálica en marcos de ventana, y enmarca las ventanas con material cerámico que hace volar sobre los vanos, que a manera de parasol protege del sol en verano (más alto en el cielo), y permite que en invierno, al estar más bajo, pueda entrar en la vivienda.

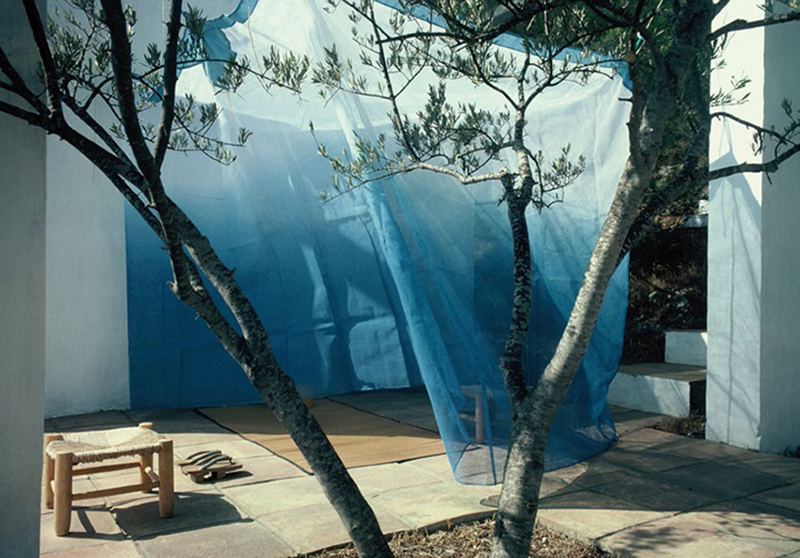

Bernard Rudofsky is famous for his critique of the ideas of standardisation and universalisation implicit in Modernism. History, culture, climate, environment, all have to be taken into account in the project. His ideas are in tune with those which, in the panorama of the evolution of 20th century architecture in the middle of the century, are proposing the place (something certain, with its symbolic, cultural, climatic charge) as an alternative to space (cold, mathematical, abstract, anonymous). This dialogue with the terrain, letting oneself be carried away by its suggestions or giving way to vegetation, offers one of its most exquisite examples in this holiday home which had no telephone, radio or television, but housed works of art, from Calder to Christo to the Eames or Le Corbusier. Unlike architects who dematerialise the wall of the house with glass walls, Bernard Rudofsky offered a more Mediterranean version, an “open-air” house or “habitable garden”. As the architect explained, this idea of housing was already “understood long before the revolutions of the 20th century”, coming from the Greco-Roman world: open-air living rooms, rooms without roofs, but still always considered as rooms. Rudofsky had already experimented with this device in the Arnstein House in Sao Paulo, where every interior space had a corresponding outdoor area joined by a porch.

Bernard Rudofsky es célebre por su crítica de las ideas de estandarización y universalización implícitas en lo moderno. Historia, cultura, clima, entorno, han de verse acogidos en el proyecto. Sus ideas están a tono con aquellas que, en el panorama de la evolución de la arquitectura del XX, a mediados de siglo, están proponiendo el lugar (algo concreto, con su carga simbólica, cultural, climática), como alternativa al espacio (frío, matemático, abstracto, anónimo). Ese diálogo con el terreno, el dejarse llevar por sus sugerencias o ceder el lugar a la vegetación, ofrece uno de sus más exquisitos ejemplos en esta casa de vacaciones que carecía de teléfono, radio o televisión, albergaba obras de arte, desde Calder a Christo hasta los Eames o Le Corbusier. A diferencia de los arquitectos que desmaterializan la pared de la vivienda mediante muros de cristal, Bernard Rudofsky ofrecía una versión más mediterránea, una casa “al aire libre» o «jardín habitable”. Según explicó el arquitecto, esta idea de vivienda ya se “entendió mucho antes de las revoluciones del siglo XX”, procedente del mundo greco-romano: salas de estar al aire libre, salas sin techo, pero aún así siempre consideradas como habitaciones. Rudofsky ya había experimentado con este dispositivo en la Casa de Arnstein en Sao Paulo, donde cada espacio interior tenía un área que corresponde al aire libre unidos por un porche.

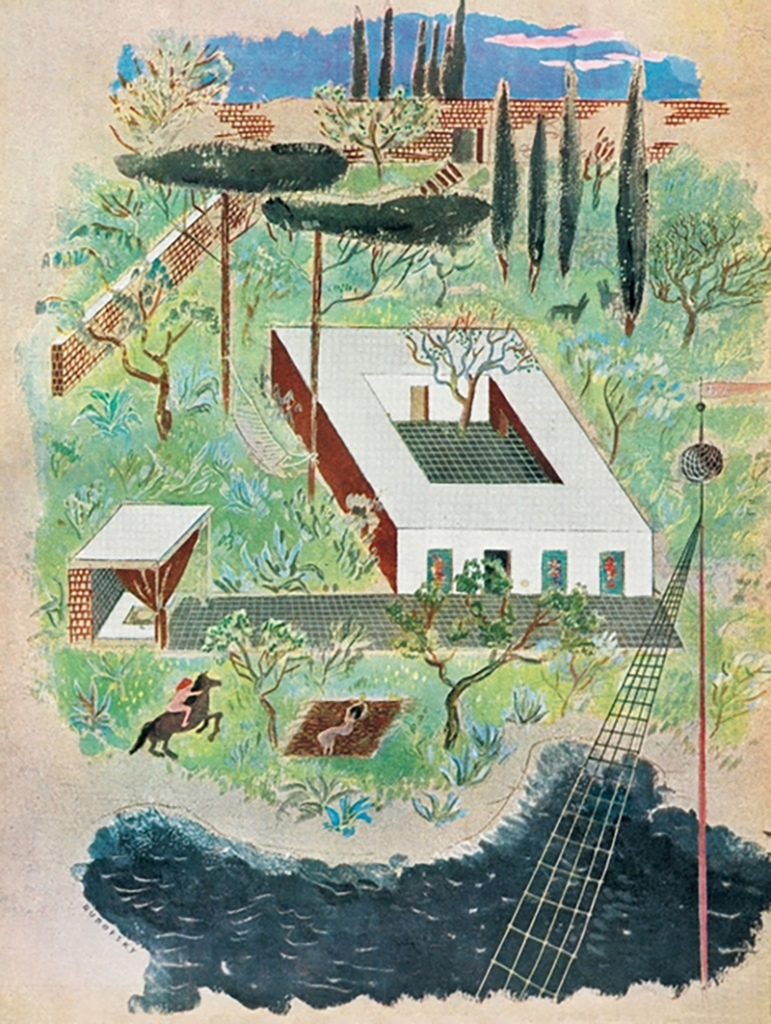

In the case of the collaboration between Bernard Rudofsky and Constantino Nivola, in their House-garden in Amagansett, New York (1949-1950), the idea was to organise the property from a sequence of “rooms” open to the air, using a combination of paths, free-standing walls, fences, and natural plants to define each area. All of these elements combine to create what Rudofsky once described as a “play of wall surfaces, sunlight and vegetation”. Near the centre of the garden, the largest of the outdoor rooms was defined by a high horizontal slatted fence painted white, a free-standing wall stuccoed and sgraffitoed by Nivola, and a third wall suggested by a row of trees. In the centre of this room, a fountain made of metal blades which, thanks to the water, simulated an “aerial staircase”. In the adjacent room, they placed an outdoor kitchen terrace, with a free-standing fireplace, a barbecue grill, and a tall white-painted chimney. Originally, the boundaries of this area were defined by a red-painted wooden structure. To further emphasise the concept of the open-air living room, he placed another free-standing wall opened by a square window through which the branch of an apple tree grows. This wall was left white, so that the shadows of the tree moved across its surface, creating a kind of kinetic mural, and the wall became a sculptural “projection screen”.

En el caso de la colaboración entre Bernard Rudofsky y Constantino Nivola, en su House-garden en Amagansett, Nueva York ( (1949-1950), la idea era organizar la propiedad a partir de una secuencia de “habitaciones” abiertas al aire, utilizando una combinación de caminos, paredes independiente, vallas, y las plantas naturales para definir cada área. Todos estos elementos se combinan para crear lo que Rudofsky una vez describió como un «juego de las superficies de las paredes, la luz del sol y la vegetación». Cerca del centro del jardín, la mayor de las salas al aire libre fue definida por una alta valla de listones horizontales pintadas de blanco, un muro independiente estucado y esgrafiado por Nivola, y una tercera pared sugerida por una hilera de árboles. En el centro de esta sala, una fuente hecha de palas metálicas que gracias al agua simulaba una “escalera aérea”. En la habitación adyacente, situaron una terraza cocina al aire libre, con una chimenea independiente, una parrilla de barbacoa, y una alta chimenea pintada de blanco. Originalmente, los límites de esta área los definía una estructura de madera pintada de rojo. Para enfatizar aún más el concepto de la sala al aire libre, coloca otro muro independiente abierto por una ventana cuadrada a través del cual crece la rama de un manzano. Este muro se quedó blanco, para que las sombras del árbol se movieran a través de su superficie, creando una especie de mural cinético, y la pared se convirtiera en una “pantalla de proyección” escultórica.

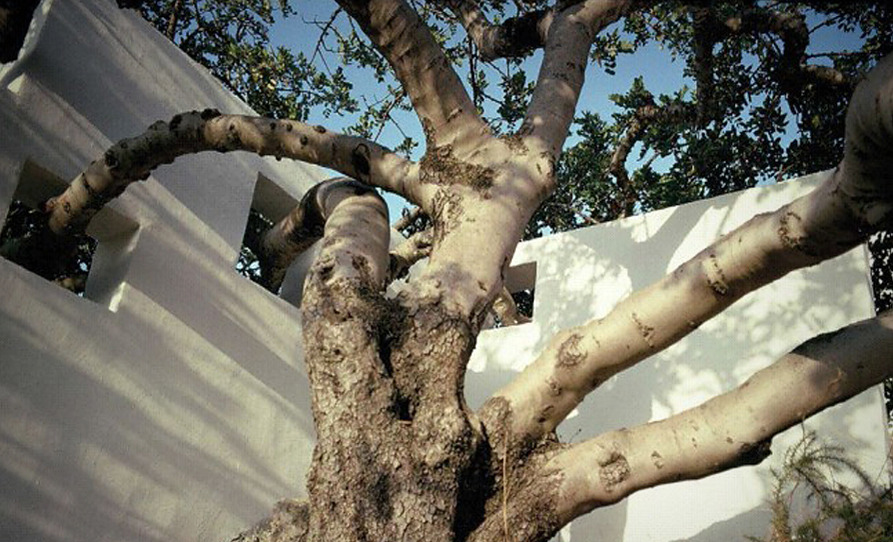

And a synthesis of this whole idea could be the image of the hundred-year-old carob tree on the estate, whose arms cross a corner wall that neither supports nor closes off anything, but rather orders the space and links the architecture with nature. This same resource is used by Rudofsky in his collaboration with the Italian sculptor Constantino Nivola in designing his house-garden in Amagansett, New York (1940), where a tree grows through openings in a wall that lead to an understanding of architecture with its surroundings, and the careful intervention of man in nature. These walls, known in gardening circles as “Rudofsky walls”, base their philosophy on the idea that the wall is an element of stability in the midst of a constantly changing plant world. The architect’s intention in using these walls is to add to the architecture the changing play of light and shadow cast by the vegetation on the light-coloured wall. But it also adds a functional quality by serving as a windbreak for the plants and as a visual barrier.

Y síntesis de todo este ideario podría ser la imagen del algarrobo centenario que existe en la finca, cuyos brazos atraviesan un muro de esquina que no sustenta ni cierra nada, sino que ordena el espacio, y enlaza la arquitectura con la naturaleza. Este mismo recurso lo utiliza Rudofsky en su colaboración con el escultor italiano Constantino Nivola al diseñar su house-garden en Amagansett, Nueva York (1940), donde un árbol crece a través de las aberturas realizadas en un muro que llevan al entendimiento de la arquitectura con su entorno, y a la cuidadosa intervención del hombre en la naturaleza. Estos muros conocidos en jardinería como “paredes Rudofsky” sustentan su filosofía en la idea de que el muro es un elemento de estabilidad en medio del mundo vegetal en constante cambio. La intención del arquitecto al utilizar estas paredes es añadir a la arquitectura el juego cambiante de las luces y sombras que proyecta la vegetación sobre el muro de color claro. Pero también se añade una cualidad funcional al servir como contraviento para las plantas y como barrera visual.

Text from Arquitectura de Málaga

VIA: