***

Title: In Search of African American Space

Author: Jeffrey Hogrefe, Scott Ruff, with Carrie Eastman and Ashley Simone

Edited by: Lars Müller Publishers

2020. ISBN: 978-3-03778-633-8

Language: English

256 pages

“What is African American space? It is a concept perhaps best understood in its simplest incarnation as environments that allow Black communities to thrive. They are spaces that remedy cen- turies of precarity and enclosure, which have limited the capacity for our people to realize their potential to live unbounded lives. They are spaces that refuse cultural, political, or economic circumstances that diminish, degrade, dehumanize, and destroy Black life. The creation of African American space is, at its core, a practice of refusal.”

¿Qué es el espacio afroamericano? Es un concepto que quizás se entienda mejor en su encarnación más simple como entornos que permiten a las comunidades negras prosperar. Son espacios que ponen remedio a siglos de precariedad y encierro, que han limitado la capacidad de nuestra gente de realizar su potencial para vivir vidas sin límites. Son espacios que rechazan las circunstancias culturales, políticas o económicas que disminuyen, degradan, deshumanizan y destruyen la vida de los negros. La creación del espacio afroamericano es, en su esencia, una práctica de rechazo.

Tina M.Campt, page 12

The first enslaved Africans were captured and transported to North America in 1619. More than two and a half centuries later, the Constitution of the United States of America declared slavery illegal, except for the exception of imprisonment. As is well known to all, this constitutional declaration does not mean equal rights for all people, for all those of African-American origin will have to struggle to this day to finally bury centuries of oppression and unjustifiable violence. Sadly, the news almost every week reminds us of the long road that still lies ahead to eliminate all forms of discrimination. Millions of people continue to suffer every day from the violence of colonialist thinking that used the enslavement of people to exploit their labour force.

Las primeras personas africanas esclavizadas fueron capturadas y transportadas a América del Norte en el año 1619. Más de dos siglos y medio después, la Constitución de los Estados Unidos de América declara la esclavitud ilegal, salvo con la excepción de encarcelamiento. Como es bien conocido por todos, esta declaración constitucional no supone la igualdad de derechos para todas las personas, pues todos aquéllos de origen afroamericano deberán luchar hasta nuestros días para enterrar definitivamente siglos de opresión y violencia injustificable. Lamentablemente, las noticias de actualidad nos recuerdan casi cada semana el largo camino que aún queda por recorrer hasta la eliminación de toda clase de discriminación. Millones de personas continúan sufriendo cada día la violencia procedente del pensamiento colonialista que utilizó la esclavización de personas para la explotación de su fuerza de trabajo.

If the African American experience emerges from the structure of slavery, how can architecture, construction and spatial perception relate to this experience? How can people of African American origin respond to an architectural experience that from its inception reinforces the oppressive role of the states that enslaved them? How to build now, how to even think about the space of a collective of people who were stripped of everything, including their very nature as human beings?

Si la experiencia afroamericana emerge de la estructura de la esclavitud, ¿cómo puede la arquitectura, la construcción y percepción espacial relacionarse con esta experiencia? ¿Cómo pueden responder las personas de origen afroamericano a una experiencia arquitectónica que desde sus inicios refuerza el papel opresor de los estados que les esclavizaron? ¿Cómo construir ahora, cómo tan siquiera pensar en el espacio de un colectivo de personas que fueron despojadas de todo, incluso de su naturaleza misma de ser humano?

“African American studies scholars contend that the passage from slavery to freedom does not begin in legal structures that convey partial citizenship. Rather, freedom develops through both historical and contemporary processes of self-making and by appropriating spaces of resistance in which to anticipate future liberty and self-possession. Despite near constant surveillance, enslaved Africans gathered covertly to practice freedom in “hush harbors” at the fringes of slave plantations, in the oral traditions of praise meetings, and through quilting parties and juba dances that marked celebratory occasions. In undertaking such activities, enslaved persons adapted the phrasing of their masters by sardonically announcing that they were “stealing away”-since they did not legally possess their own bodies. The first order of appropriation enacted in this practice of freedom, and the collective sharing of an informal geography that encouraged escape from slavery, each demonstrate the complex ways in which space could be remade even in captivity.“

“Los estudiosos afroamericanos sostienen que el paso de la esclavitud a la libertad no comienza en las estructuras legales que transmiten una ciudadanía parcial. Más bien, la libertad se desarrolla a través de procesos históricos y contemporáneos de creación de sí mismo y de la apropiación de espacios de resistencia en los que anticipar la libertad y la autoposesión futuras. A pesar de la vigilancia casi constante, los africanos esclavizados se reunían de forma encubierta para practicar la libertad en “refugios de silencio” en los márgenes de las plantaciones de esclavos, en las tradiciones orales de las reuniones de alabanza y en las fiestas de acolchado y los bailes juba que marcaban las ocasiones de celebración. Al llevar a cabo estas actividades, las personas esclavizadas adaptaban las frases de sus amos anunciando con sorna que estaban “robando”, ya que no poseían legalmente sus propios cuerpos. El primer orden de apropiación promulgado en esta práctica de la libertad, y el intercambio colectivo de una geografía informal que animaba a escapar de la esclavitud, demuestran las complejas formas en que el espacio podía rehacerse incluso en el cautiverio.”

Jeffrey Hogrefe, page 22

The answers to each of these questions seem unattainable. At Hidden Architecture we have always sought to unveil more or less hidden, forgotten practices within the discipline of architecture. When the reason for this oblivion, this denial, responds to editorial positions structured from ideological aspects, we can easily respond to them from our position of resistance. But what happens when the origin of this denial lies in the darkest part of human nature? Just as it has happened and continues to happen with other collectives, the ideological construction of Western historiographical narratives mask, codify, hide, annul and even destroy African-American culture. How can we fight against this? How, in our case as architects, can we begin to appreciate, to understand the construction of a vision of African American space? How can we lay the foundations for a critical approach to this or similar issues that would be structurally embedded in the university programmes that educate the architects of tomorrow?

Las respuestas a cada una de estas preguntas se nos antojan inalcanzables. Desde Hidden Architecture siempre hemos pretendido desvelar prácticas más o menos ocultas, olvidadas, dentro de la disciplina arquitectónica. Cuando el motivo de este olvido, esta negación, responde a posicionamientos editoriales estructurados desde aspectos ideológicos, podemos responder fácilmente frente a ellos desde nuestra posición de resistencia. Pero, ¿qué sucede cuando el origen de esa negación se encuentra en lo más oscuro de la naturaleza humana? Del mismo modo que ha sucedido y continúa sucediendo con otros colectivos, la construcción ideológica de las narrativas historiográficas occidentales enmascaran, codifican, esconden, anulan e incluso destruyen la cultura afroamericana. ¿Cómo podemos luchar contra esto? ¿De qué manera, en nuestro caso como arquitectos, podemos comenzar a apreciar, a entender la construcción de una visión del espacio afroamericano? ¿Cómo podríamos sentar las bases para un acercamiento crítico a esta problemática, u otras análogas, que se asentara de manera estructural en los programas universitarios que educan a los arquitectos del mañana?

“The front porch was often added to the typical shotgun house in reference to the West African veranda. For Blacks compelled to live on the “other side of the tracks,” experiencing the city meant crossing the street when whites approached and for traveling by way of networked back alleys. In this context, the porch served not solely as a casual intermediate space, but also as a multiuse environment that expanded the possibilities for a public and private performance since it could either be opened or closed to the street. As both part of the private home and a semipublic social space, the porch was a place from which to see, and to be seen, outside the gaze of white authority.” And today the porch remains a site where African American people radically engage with the public sphere. In urban environments throughout the United States, the stoop and the street corner have substituted for this particular structural role of the porch. The greater visibility of the stoop and street corner also make them richer and more dynamic sites for performing opposition, or appropriating space for possible redress. These sites are commonly seen as free spaces of gathering for residents and passers-by, as depicted in the film “Do the Right Thing” (1989), which circulates through the social collectivity of a number of stoops on one block in Brooklyn. The public-private mediation of performances staged on both porch and stoop also indicates the uneasy relationship of the African American person to spaces that regulate the body and demand a state of hypervigilance. As vestiges of an ancient African architectural form, these sites and their continued proliferation are central to the development of African American subjectivity.”

“El porche delantero se añadía a menudo a la típica “casa de escopeta” en referencia a la veranda del África occidental. Para los negros que se veían obligados a vivir en el “otro lado de las vías”, experimentar la ciudad significaba cruzar la calle cuando los blancos se acercaban y desplazarse a través de una red de callejones traseros. En este contexto, el porche no sólo servía como espacio intermedio casual, sino también como un entorno multiuso que ampliaba las posibilidades de una actuación pública y privada, ya que podía abrirse o cerrarse a la calle. Como parte del hogar privado y espacio social semipúblico, el porche era un lugar desde el que ver, y ser visto, fuera de la mirada de la autoridad blanca”. Y hoy en día el porche sigue siendo un lugar en el que los afroamericanos se relacionan radicalmente con la esfera pública. En los entornos urbanos de Estados Unidos, la entrada y la esquina de la calle han sustituido el papel de la estructura rural del porche. La mayor visibilidad de la acera y de la esquina de la calle también las convierte en lugares más ricos y dinámicos para llevar a cabo la oposición, o para apropiarse del espacio para una posible reparación. Estos lugares suelen considerarse espacios libres de reunión para los residentes y los transeúntes, como se muestra en la película “Do the Right Thing” (1989), que circula a través de la colectividad social de varios porches de una manzana de Brooklyn. La mediación público-privada de las actuaciones escenificadas tanto en el porche como en la banqueta también indica la incómoda relación de la persona afroamericana con los espacios que regulan el cuerpo y exigen un estado de hipervigilancia. Como vestigios de una antigua forma arquitectónica africana, estos lugares y su continua proliferación son fundamentales para el desarrollo de la subjetividad afroamericana.”

Scott Ruff, Cultural Translations and Tropes of African American Space, page 84

“In Search of African American Space”, a book published by Lars Müller Publishers, is one of the first publishing works in the field of architecture that aims to contextualise and make this problem visible and thus answer all the questions we might ask. According to the book’s introduction, the origin of “In Search of African American Space” goes back to a symposium of the same name held in 2016 in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, a neighbourhood with a strong African American tradition. Under the auspices of the Pratt Institute and following the explosion of the Black Lives Matter activist movement, it evolved until part of the works developed were collected in this volume.

“In Search of African American Space”, libro editado por Lars Müller Publishers, es uno de los primeros trabajos editoriales dentro del ámbito de la arquitectura que pretende contextualizar y visibilizar esta problemática y responder así a todas las preguntas que podamos formular. Según se nos cuenta en la introducción del libro, el origen de “In Search of African American Space” se remonta a la celebración de un simposio homónimo celebrado en el año 2016 en el barrio de Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, barrio de fuerte tradición afroamericana. Bajo el amparo de Pratt Institute y tras la explosión del movimiento activista Black Lives Matter evoluciona hasta que parte de los trabajos desarrollados queden recogidos en este volumen.

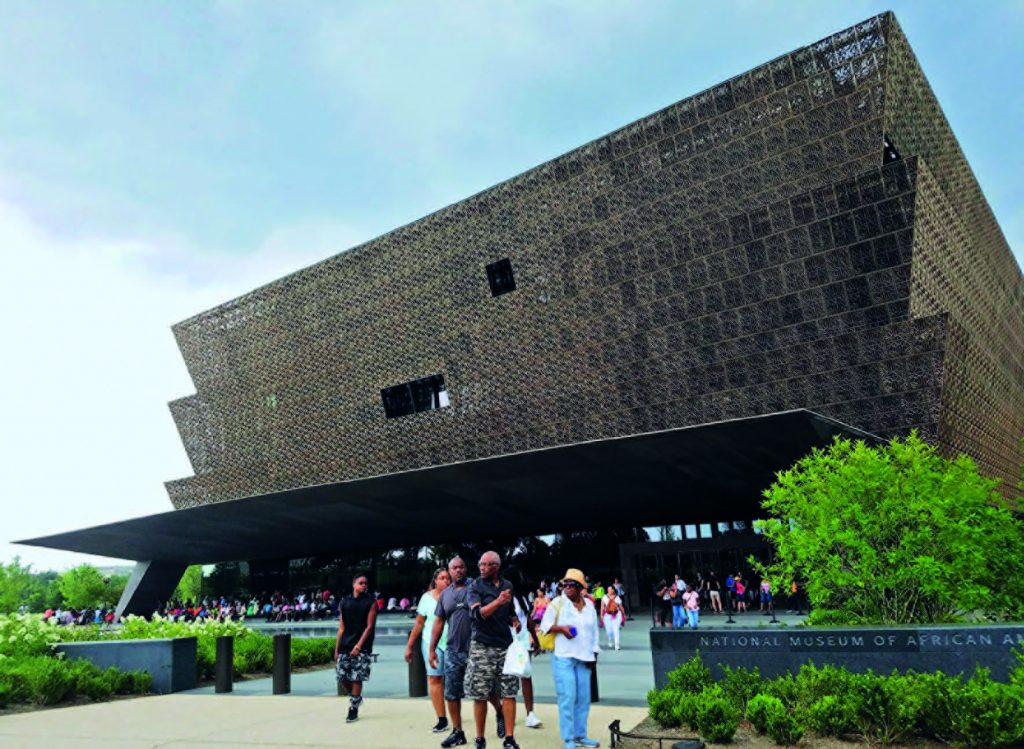

Thus, the work published by Lars Müller Publishers is a compilation of articles that, from different disciplines and perspectives, come close to outlining interpretations of certain readings of what we could call the construction, or rather, the unveiling of the African American space. This anthology of texts is structured in three different blocks. In the first of these, “Politics without proper Locus”, we find three articles that approach the interpretation of African American space from a more academic perspective. The first two construct a historiographical and anthropological framework of the situation of enslaved people in the United States at two different times and places. The third article, which closes the first block, is the one that develops the most architectural argumentation of the whole book. In “Cultural Translations and Tropes of African American Space”, architect Scott Ruff traces a journey through different architectural typologies and spatial patterns closely linked to the African American community, and ends by relating these concepts to the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, located on the Washington Mall, as well as the Monticello dwelling built by Thomas Jefferson.

Así, la obra editada por Lars Müller Publishers es una recopilación de artículos que, desde diferentes disciplinas y perspectivas, se aproximan a esbozar interpretaciones sobre unas determinadas lecturas de los que podríamos llamar la construcción, o, mejor, el desvelamiento del espacio afroamericano. Esta antología de textos está estructurada en tres bloques diferentes. En el primero de ellos, “Politics without proper Locus”, nos encontramos con tres artículos que realizan una aproximación a la interpretación del espacio afroamericano desde una perspectiva más académica. Los dos primeros construyen un marco historiográfico y antropológico de la situación de las personas esclavizadas en los Estados Unidos en dos momentos y lugares diferentes. El tercer artículo, que cierra el primer bloque, es el que desarrolla una argumentación más arquitectónica de todo el libro. En “Cultural Translations and Tropes of African American Space” el arquitecto Scott Ruff traza un recorrido por diferentes tipologías arquitectónicas y patrones espaciales muy vinculados a la comunidad afroamericana, para terminar relacionando estos conceptos con el nuevo National Museum of African American History and Culture, ubicado en el Washington Mall, pasando también por la vivienda de Monticello, construida por Thomas Jefferson.

“Vernacular citizenship signifies the words and deeds developed in response to the denial of political subjectivity to people of African descent in the Americas. It articulates a demand for a participatory and expansive, all-inclusive democracy. Vernacular citizenship bypassed the technical.and legal exclusions of formal citizenship, and relied instead on presence and action: the mutually substantiated performance of civic belonging by people denied personhood by the social and political order.”

“La ciudadanía vernácula significa las palabras y los hechos desarrollados en respuesta a la negación de la subjetividad política a los afrodescendientes en las Américas. Articula la demanda de una democracia participativa y expansiva que incluya a todos. La ciudadanía vernácula evitó las exclusiones técnicas y legales de la ciudadanía formal, y se basó en cambio en la presencia y la acción: la actuación mutuamente justificada de la pertenencia cívica por parte de las personas a las que el orden social y político les negaba la condición de persona.”

Ann S. Holder, The Terrain of Politics: Race, Space and Vernacular Citizenship, page 36

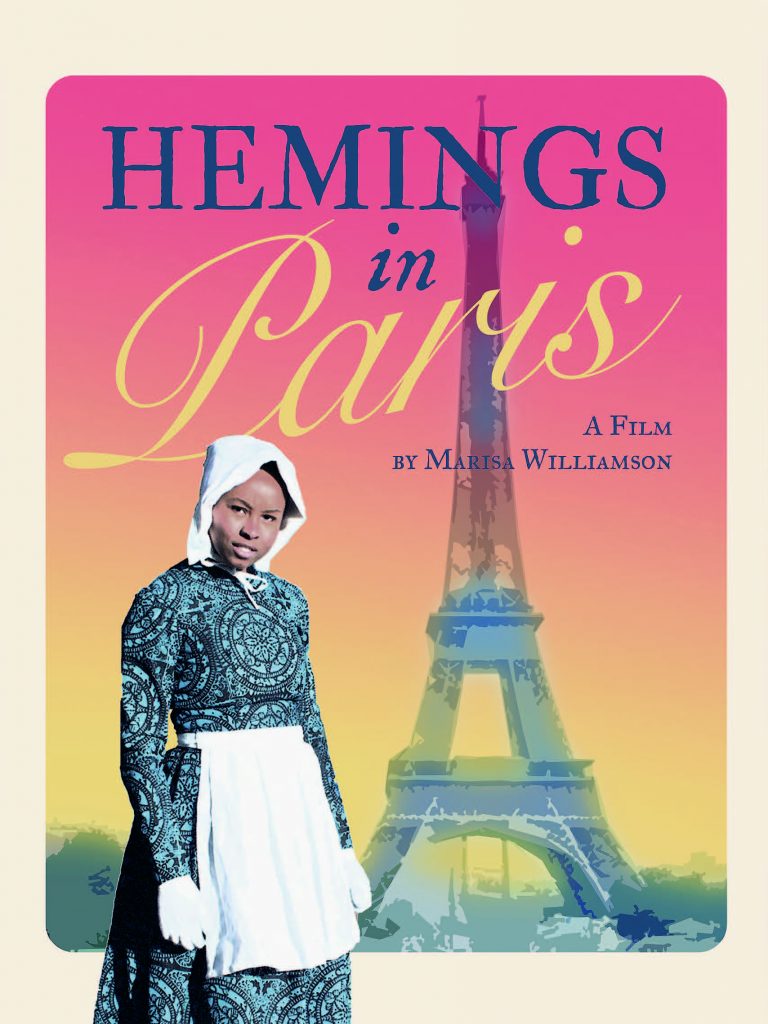

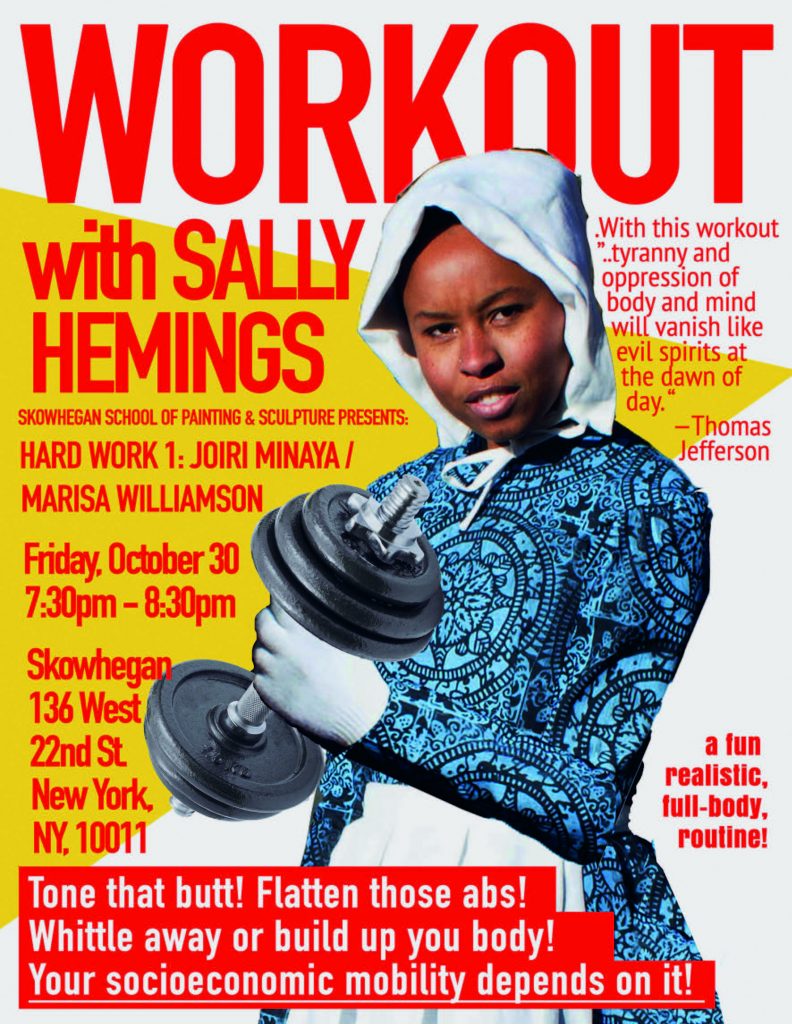

The second block of the book “Materializing Memory” presents two articles with the common intention of aiming at a transition from the disciplinary and emotional interpretation of the past to transcend into a creative practice. Finally, the block “Recording Erasure” presents three articles that develop and record different artistic projects or installations with the intention of delving into an interpretation of African American space in ephemeral events, performances or the recording of everyday activities.

El segundo bloque del libro “Materializing Memory” presenta dos artículos con la intención común de apuntar a una transición desde la intepretación disciplinar y emocional del pasado para trascender hacia una práctica creativa. Por último, el bloque “Recording Erasure” presenta tres artículos que desarrollan y registran diferentes proyectos o instalaciones artísticas con la intención de profundizar en una interpretación del espacio afroamericano en eventos efímeros, performances o el registro de actividades cotidianas.

As usual in books that are anthologies of articles by different authors, “In Search of African American Space” is characterised from a positive point of view by the complexity of insights on the same subject that it brings together. We believe that at the beginning of a discussion or approach to a topic that has not been discussed much to date, such as the construction of an idea of African American space throughout the process of liberation and struggle of a collective that comes from slavery, it is essential to contribute as many voices as possible. The book published by the Swiss publisher does not aim to construct an intellectually grounded interpretative framework with a specific critical approach. Proof of this is the total absence – and this is something we would perhaps have liked to see – of a synthesis exercise that would close the book and develop an analytical exercise on the different practices compiled in order to serve as a starting point for future work. It is true, however, that the introductory article “Spaces of Refuge and Delight” by Jeffrey Hogrefe does propose this exercise from the beginning, possibly in one of the most brilliant texts of those collected here.

Como suele ser habitual en los libros que son antologías de artículos de diferentes autores, “In Search of African American Space” se caracteriza desde un punto de vista positivo por la complejidad de miradas sobre un mismo tema que reúne. Consideramos que en los inicios de una discusión o planteamiento de un tema poco concurrido hasta la fecha, como es la construcción de una idea de espacio afroamericano a lo largo del proceso de liberación y lucha de un colectivo que procede de la esclavitud, es fundamental aportar el mayor número de voces posibles. El libro editado por la editorial suiza no ambiciona construir un marco interpretativo intelectualmente asentado y con una aproximación crítica determinada. Prueba de ello es la ausencia total, y es algo que quizá nos habría gustado ver, de un ejercicio de síntesis que cerrase el libro y desarrollase un ejercicio analítico sobre las diferentes prácticas compiladas con el fin de servir de punto de partida para futuros trabajos. Es cierto, sin embargo, que el artículo introductorio “Spaces of Refuge and Delight” de Jeffrey Hogrefe sí plantea este ejercicio desde el inicio, posiblemente en uno de los textos más brillantes de los que aquí se recogen.

“As a Black woman walking alone within a raced landscape, I began to consider a new notion of “place” to describe something beyond the built environment, beyond community, and beyond my home. As a Black woman, my body is also a “place,” a geography, which holds within it a set of “knowledges, negotiations and experiences” bequeathed to me by my ancestors who longed to be free. Walking the red lines of the map allowed me to embody the emotional struggle and complexity of this painful legacy and reclaim, if only for a moment, a Black sense of space and place that historically, my ancestors were never allowed to fully possess.”

“Como mujer negra que camina sola dentro de un paisaje racializado, comencé a considerar una nueva noción de “lugar” para describir algo más allá del entorno construido, más allá de la comunidad y más allá de mi hogar. Como mujer negra, mi cuerpo es también un “lugar”, una geografía, que alberga en su interior un conjunto de “conocimientos, negociaciones y experiencias” que me legaron mis antepasados, que anhelaban ser libres. Recorrer las líneas rojas del mapa me permitió encarnar la lucha emocional y la complejidad de este doloroso legado y reclamar, aunque sólo fuera por un momento, un sentido negro del espacio y del lugar que, históricamente, a mis antepasados nunca se les permitió poseer plenamente.”

Walis Johnson, Walking the Geography of Racism, page 196

Another characteristic that should be highlighted, and which is nothing other than the consequence of the inclusion of multiple transversal viewpoints, is the irregularity of the articles included in this anthology. We believe that there is a clear vocation to transcend the disciplinary field of architecture to reach a much wider public, and we certainly welcome this openness. On the other hand, and as architects who recognise their lack of training and preparation to work on the issues reflected here, we would have liked to find, selfishly, a more intense exercise of approach from the architectural discipline. In this respect, we would especially like to celebrate the articles that make up the first half of the book, between the first and second blocks mentioned above, as they provide us with interpretative tools from History and Architecture that are fundamental for constructing a necessary critique of the construction and understanding of African American space.

Otra característica que cabría destacar, y que no es otra cosa que la consecuencia de la inclusión de múltiples miradas transversales, es la irregularidad de los artículos recogidos en esta antología. Creemos entender que existe una vocación clara de trascender el ámbito disciplinar de la arquitectura para llegar a un público mucho más amplio, y desde luego nosotros celebramos esta apertura. Por el contrario, y como arquitectos que reconocen su nula formación y preparación para trabajar sobre las problemáticas aquí reflejadas, nos habría gustado encontrar, egoístamente, un ejercicio más intenso de aproximación desde la disciplina arquitectónica. A este respecto, queremos celebrar especialmente los artículos que componen la primera mitad del libro, entre los bloques primero y segundo anteriormente citados, pues de ellos recogemos herramientas interpretativas desde la Historia y la Arquitectura fundamentales para construir una crítica necesaria de la construcción y entendimiento del espacio afroamericano.

To sum up, we must only welcome once again the publication of “In Search of African American Space” by Lars Müller Publishers. From an excellent editorial work, an admirable effort is made to make visible an architectural spatial culture developed by the African American community from the abolition of slavery to the present day. Celebrating at the same time the transversality, complexity and heterogeneity of the voices gathered, in spite of the notes made above, we claim from our position the immediate inclusion of this type of perspectives in the academic formation of Architecture. With the conviction that architects who are not capable of knowing and interpreting this type of experiences will find it difficult to respond to the different problems that current and future societies may pose to them, demanding solutions. “In Search of African American Space” is a necessary companion for the beginning of the long road to be travelled to make visible and recover all that has been denied.

Dicho esto, nos quedaría tan sólo celebrar una vez más la publicación de “In Search of African American Space” por parte de Lars Müller Publishers. Desde un trabajo editorial excelente, se realiza un esfuerzo admirable para visibilizar una cultura espacial arquitectónica desarrollada por la comunidad afroamericana desde la abolición de la esclavitud hasta nuestro días. Celebrando al mismo tiempo la transversalidad, complejidad y heterogeneidad de voces reunidas, a pesar de los apuntes antes realizados, reivindicamos desde nuestra posición la inclusión inmediata de este tipo de perspectivas en la formación académica de Arquitectura. Con la convicción de que los arquitectos que no sean capaces de conocer e interpretar este tipo de experiencias difícilmente podrán dar respuesta a los diferentes problemas que las sociedades presentes y futuras puedan plantearles demandando soluciones. Para el inicio del largo camino que nos queda por recorrer para visibilización y recuperación de todo aquello que ha sido negado, “In Search of African American Space” es un compañero de viaje necesario.