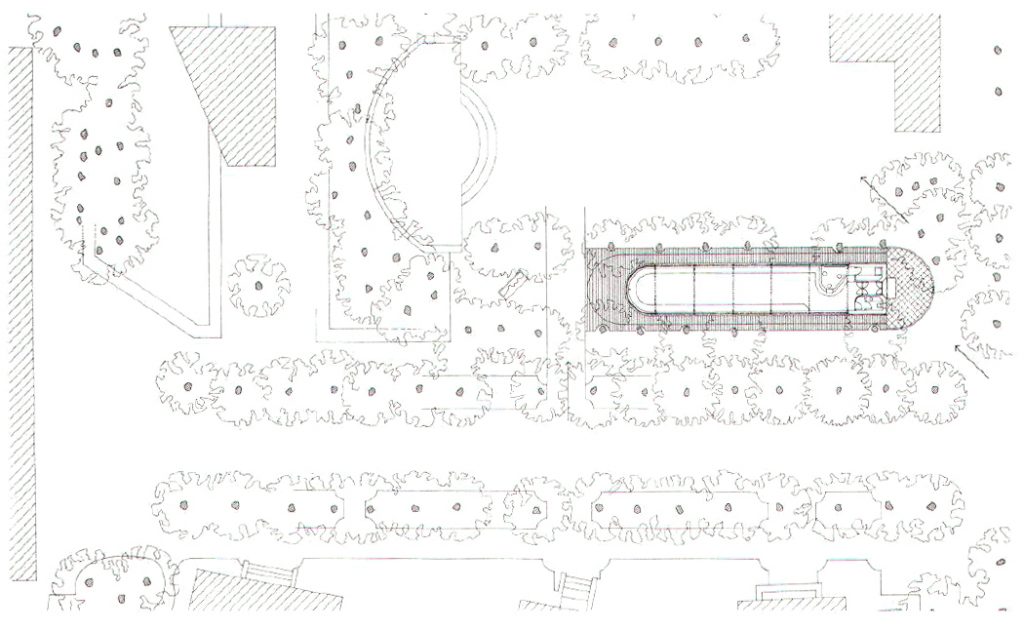

To speak of the book pavilion is first to evoke things past, namely the two rows of trees between which the architectural office of Stirling Wilford & Associates situated their building in 1991. With the exception of two or three, these trees have since disappeared, and the book pavilion now stands on a surface sparsely covered with grass. The park has undoubtedly been neglected. Even more than for other buildings in the Giardini, earlier visits to the pavilion need to be brought to mind to regain the meaning of this poetic design.

Hablar del pabellón del libro es, en primer lugar, evocar cosas del pasado, concretamente las dos hileras de árboles entre las que el estudio de arquitectura Stirling Wilford & Associates situó su edificio en 1991. A excepción de dos o tres, estos árboles han desaparecido desde entonces, y el pabellón del libro se levanta ahora sobre una superficie escasamente cubierta de hierba. No cabe duda de que el parque ha sido descuidado. Incluso más que en el caso de otros edificios de los Giardini, es necesario traer a la memoria las visitas anteriores al pabellón para recuperar el significado de este diseño poético.

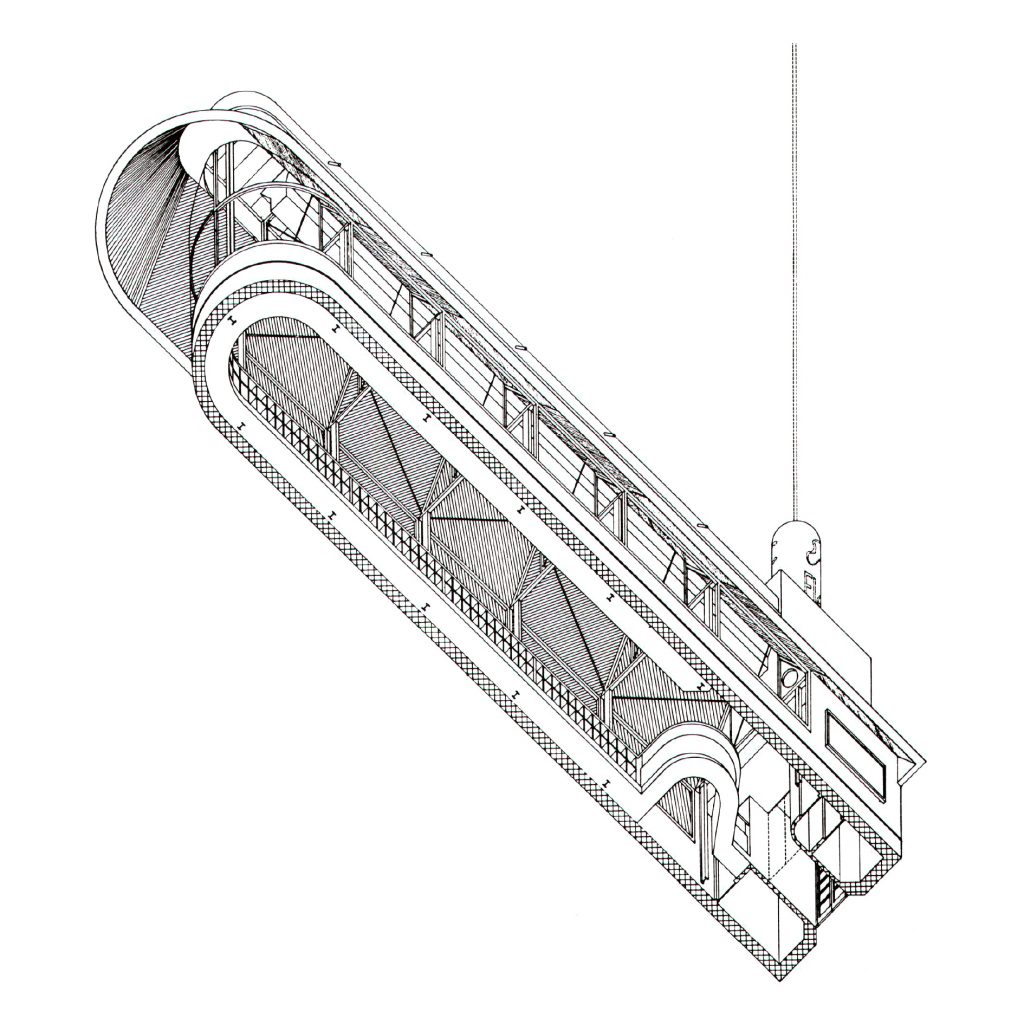

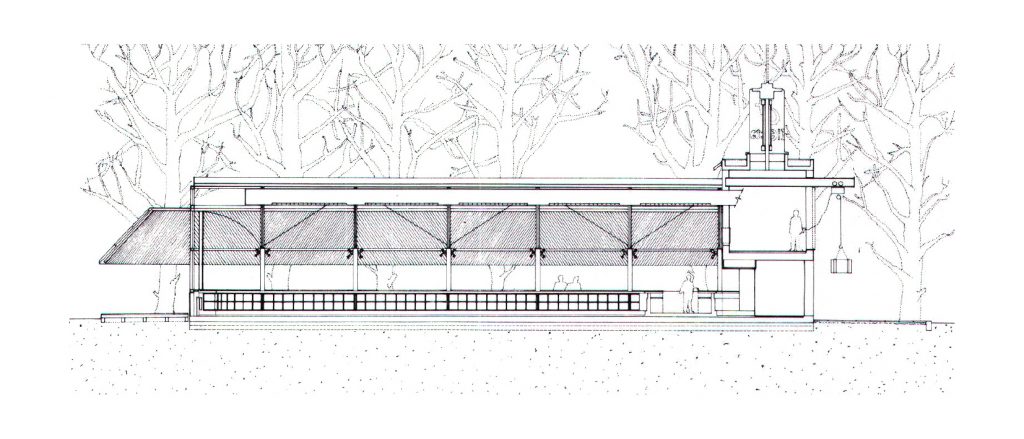

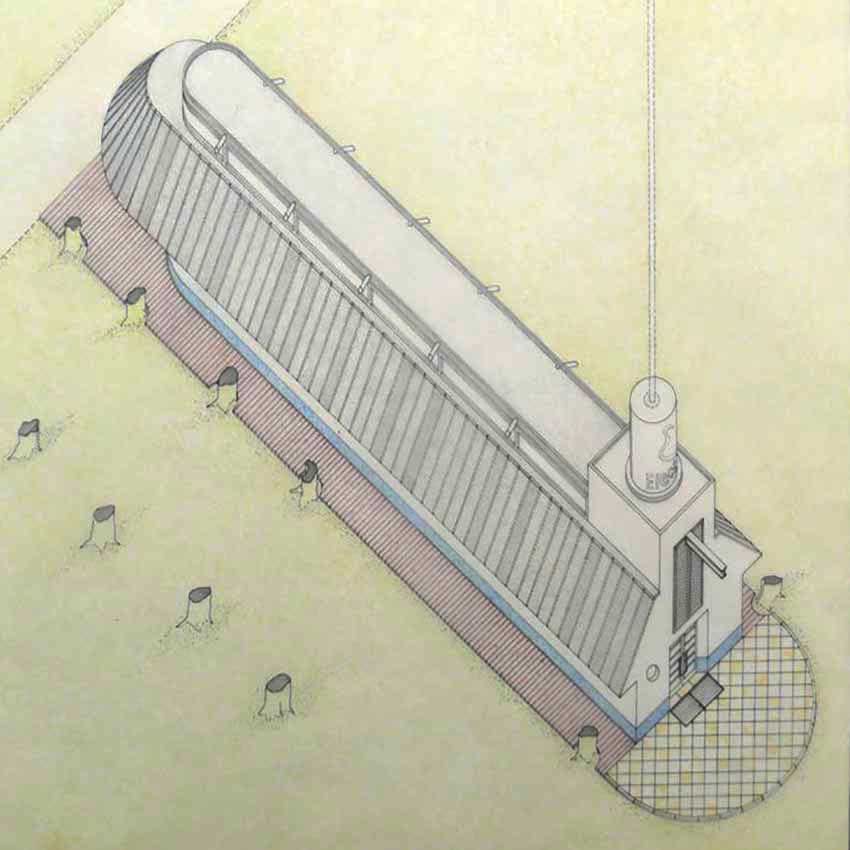

Even before the visitor takes the path to the biennial pavilion with its massive white pillars, a building appears on the right, set back behind bushes. This is somewhat unsettling given how its façade asserts a striking axis with the facing entrance to the Giardini. A short white “tower” with a grating above the door stands on a semicircular platform tiled with cement. However, the iron I-beam puncturing this grating and extending far outward disrupts my initial associations with a northern village church. Instead it brings other, industrial images to bear, or at least it is reminiscent of a goods lift. In effect, the beam serves to hoist the necessary machinery for the pavilion’s air-conditioning to the room above the door.

Incluso antes de que el visitante tome el camino hacia el pabellón de la bienal, con sus enormes pilares blancos, aparece un edificio a la derecha, replegado tras unos arbustos. Esto resulta un tanto inquietante, dado que su fachada afirma un llamativo eje con la entrada que da a los Giardini. Una corta “torre” blanca con una reja sobre la puerta se alza sobre una plataforma semicircular embaldosada con cemento. Sin embargo, la viga de hierro en forma de I que perfora esta reja y se extiende hacia el exterior altera mis asociaciones iniciales con una iglesia de pueblo del norte. En lugar de ello, trae otras imágenes industriales, o al menos recuerda a un montacargas. En efecto, la viga sirve para elevar la maquinaria necesaria para la climatización del pabellón hasta la sala situada sobre la puerta.

A further element on the tower comes into view between the trees and evokes a third association: The large yellow pipe brings to mind the chimney on one of the ships that ferried us to the Giardini. While initially painted white, it is now a color frequently found in Venice. The red “E” for “Electa” remains. The colored beam of a laser points to the night sky, or at least it used to. Even on its first appearance, the pavilion evokes contradictory and commingling images that resist coming together to a single meaning. From its symbolic façade the pavilion extends back beneath a steeply inclined roof topped with a lantern. Gaps in the surrounding wooden deck still indicate where the trees used to stand and how accurately the pavilion was located between them. The green copper roof overhangs the windows that wrap around the long, narrow room like a ribbon. Fine ribs structure the wide roof and secure the copper sheets. Its color conjures up the kind of Chinese pavilions sometimes found in an 18th-century park—however, there is no gold. The cement balustrade, painted grey along the bottom part and white along the top, makes the pavilion look like a Vaporetto.

Otro elemento de la torre aparece entre los árboles y evoca una tercera asociación: El gran tubo amarillo recuerda a la chimenea de uno de los barcos que nos llevaron a los Giardini. Aunque inicialmente se pintó de blanco, ahora es un color que se encuentra con frecuencia en Venecia. La “E” roja de “Electa” permanece. El haz de color de un láser apunta al cielo nocturno, o al menos lo hacía. Incluso en su primera aparición, el pabellón evoca imágenes contradictorias y mezcladas que se resisten a confluir en un único significado. Desde su simbólica fachada, el pabellón se extiende hacia atrás bajo un tejado muy inclinado rematado por una linterna. Los huecos en la cubierta de madera que lo rodea siguen indicando dónde se encontraban los árboles y con qué precisión se situaba el pabellón entre ellos. El tejado de cobre verde sobresale de las ventanas que envuelven la larga y estrecha estancia como una cinta. Unas finas nervaduras estructuran el amplio techo y aseguran las láminas de cobre. Su color evoca el tipo de pabellones chinos que a veces se encuentran en un parque del siglo XVIII; sin embargo, no hay oro. La balaustrada de cemento, pintada de gris en la parte inferior y de blanco en la superior, hace que el pabellón parezca un Vaporetto.

Text by Martin Steinman

VIA:

Werk, Bauen und Wohnen 78, 1991

Archeyes