Domestic astronomy is the prototype of an apartment where you no longer occupy a surface, you occupy an atmosphere. As they leave the floor, the functions and furnishings rise: they spread and evaporate in the atmosphere of the apartment, and they stabilize at certain temperatures determined by the body, clothing, and activity. Our proposal is to make allowances for these physical differences in the distribution of temperature in space and to exploit them by changing the way of life, to replace a horizontal way of living with a vertical one where we can occupy different heat zones, different layers, and different heights. Thus, to create a global ecosystem like a kind of astronomy in the home, where combinations of temperature, lights, time, and place are reconfigured.

Domestic astronomy es un prototipo para un apartamento donde ya no se ocupa una superficie, se ocupa una atmósfera. Al abandonar el suelo, las funciones y el mobiliario aumentan: se esparcen y se evaporan en la atmósfera del apartamento y se estabilizan a temperaturas determinadas por el cuerpo, la vestimenta y la actividad. Nuestra propuesta es tener en cuenta estas diferencias físicas en la distribución de la temperatura en el espacio y explotarlas cambiando la forma de vida; sustituir una forma de vida horizontal por una vertical donde podamos ocupar diferentes zonas de calor, diferentes capas, diferentes alturas. Y así crear un ecosistema global como una especie de astronomía en el hogar, donde se reconfiguran combinaciones de temperatura, luces, tiempo y lugar.

According to the law of Archimedes, hot air rises while cold air descends, and this physical reality has a direct influence on the distribution of temperatures inside the apartment. One can measure large disparities in temperature between the floor and the ceiling. For example, it will be 19 degrees Celsius at the level of the feet and 28 degrees Celsius, three meters above that, right under the ceiling. That temperature difference is absolutely useless and even becomes a problem today in the face of global warming, against which the politics of sustainable development are fighting by reducing energy consumption in building interiors. In effect, these 8 degrees Celsius above 20 degrees Celsius, which one finds just under the ceiling, are wasted energy that benefits no one.

Según la ley de Arquímedes, el aire caliente asciende mientras que el aire frío desciende, y esta realidad física influye directamente en la distribución de las temperaturas en el interior del apartamento. Se pueden medir grandes diferencias de temperatura entre el suelo y el techo. Por ejemplo, habrá 19 grados centígrados a la altura de los pies y 28 grados centígrados, tres metros por encima, justo debajo del techo. Esta diferencia de temperatura es absolutamente inútil e incluso se convierte hoy en día en un problema ante la cuestión del calentamiento global, contra el que luchan las políticas de desarrollo sostenible reduciendo el consumo de energía en el interior de los edificios. En efecto, estos 8 grados centígrados por encima de los 20 grados centígrados, que se encuentran justo debajo del techo, son energía desperdiciada que no beneficia a nadie.

Our purpose today is to take into account these physical disparities in the distribution of temperatures in space and to take advantage of them to transform the way of inhabiting space by leaving the exclusivity of a horizontal mode of habitation in the interior for a vertical mode of inhabitation where one can inhabit different thermal zones, different strata, and different altitudes.

Nuestro propósito es tener en cuenta estas disparidades físicas en la distribución de las temperaturas en el espacio y aprovecharlas para transformar la forma de habitarlo dejando la exclusividad de un modo de vida horizontal en el interior por un modo de habitar vertical. donde se pueden habitar diferentes zonas térmicas, diferentes estratos y diferentes altitudes.

In order to economize energy, the Swiss Standard for Construction (SIA) recommends heating the different spaces of the house to different temperatures to optimize the energy spent as a function of the activity and the dress of its users. Accordingly, the spaces where one is naked will be heated more intensely, while the spaces through which one merely passes or those where one is dressed more warmly must be colder. The SIA standard recommends, therefore, heating toilets to 15 degrees Celsius, the bedroom to 16 degrees Celsius, the kitchen to 18 degrees Celsius, the living room to 20 degrees Celsius, and the bathroom to 22 degrees Celsius. According to these objectives and according to the Archimedean principle of the rising of hot air, we propose splitting the program of an apartment into the entire atmosphere of a single room by looking for the different suitable temperatures for the different functions according to the different activities of the inhabitant and his clothing.

Para ahorrar energía, la norma suiza de construcción (SIA) recomienda calentar los diferentes espacios de la casa a diferentes temperaturas, con el fin de optimizar la energía gastada en función de la actividad y la vestimenta de sus usuarios. En consecuencia, los espacios en los que se está desnudo se calentarán más intensamente, mientras que los espacios por los que se pasa o en los que se abriga más deben ser más fríos. Por tanto, la norma SIA recomienda calentar los baños a 15 grados centígrados, el dormitorio a 16 grados centígrados, la cocina a 18 grados centígrados, la sala de estar a 20 grados centígrados y el baño a 22 grados centígrados. De acuerdo con estos objetivos y según el principio de Arquímedes de la subida de aire caliente, proponemos dividir el programa de un apartamento en toda la atmósfera de una sola habitación buscando las diferentes temperaturas adecuadas para las diferentes funciones según las diferentes actividades de el habitante y su vestimenta.

It is necessary then to define the sources of heat, by radiation, by convection. The artificial interior of architecture is a space where the elements that constitute the atmosphere in the natural world form an ensemble of relationships of causes and effects, constituting an ecological system where all the elements are related and interdependent in energy-related, chemical, physical, and biological exchanges. Space, light, temperature, and movement of air are, in this way, in the natural world, completely intertwined, and their variations, in large astronomical, temporal, thermodynamic, and biological movements, form the atmosphere of the planet as an ecosystem. Our purpose today is to reintroduce in the interior a sort of second astronomy whose purpose will be in no way naturalistic but, on the contrary, will come directly from the center of artificial means of creating artificial interior climates of modernity. It is in this way that we propose to reassemble a whole, to recompose in a single unit, the different climatic elements separated by the techniques of the building industry for constructing a global interior ecosystem as a new sort of astronomy of the interior where temperature, light, time, and space recombine into one single atmosphere, a single temporality, a geography.

Es necesario entonces definir las fuentes de calor, por radiación, por convección. El interior artificial de la arquitectura es un espacio donde los elementos que constituyen la atmósfera que en el mundo natural forman un conjunto de relaciones de causas y efectos, constituyendo un sistema ecológico donde todos los elementos están relacionados e interdependientes en términos energéticos, químicos, físicos. e intercambios biológicos. El espacio, la luz, la temperatura, el movimiento del aire, están así, en el mundo natural, completamente entrelazados y sus variaciones, en grandes movimientos astronómicos, temporales, termodinámicos y biológicos, forman la atmósfera del planeta como ecosistema. Nuestro objetivo hoy es reintroducir en el interior una especie de segunda astronomía cuyo objetivo no será en modo alguno naturalista sino que, por el contrario, procederá directamente del centro de los medios artificiales para crear climas interiores artificiales de modernidad. Es de esta manera que proponemos reunir un todo, recomponer en una sola unidad, los diferentes elementos climáticos separados por las técnicas de la construcción para construir un ecosistema interior global como una nueva especie de astronomía del interior donde la temperatura, La luz, el tiempo y el espacio se recombinan en una única atmósfera, una única temporalidad, una única geografía.

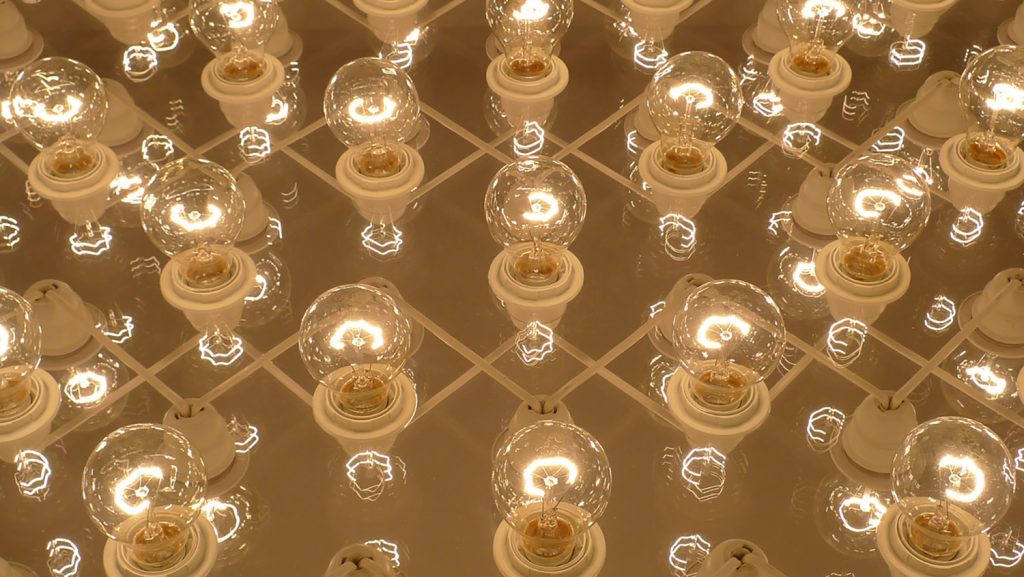

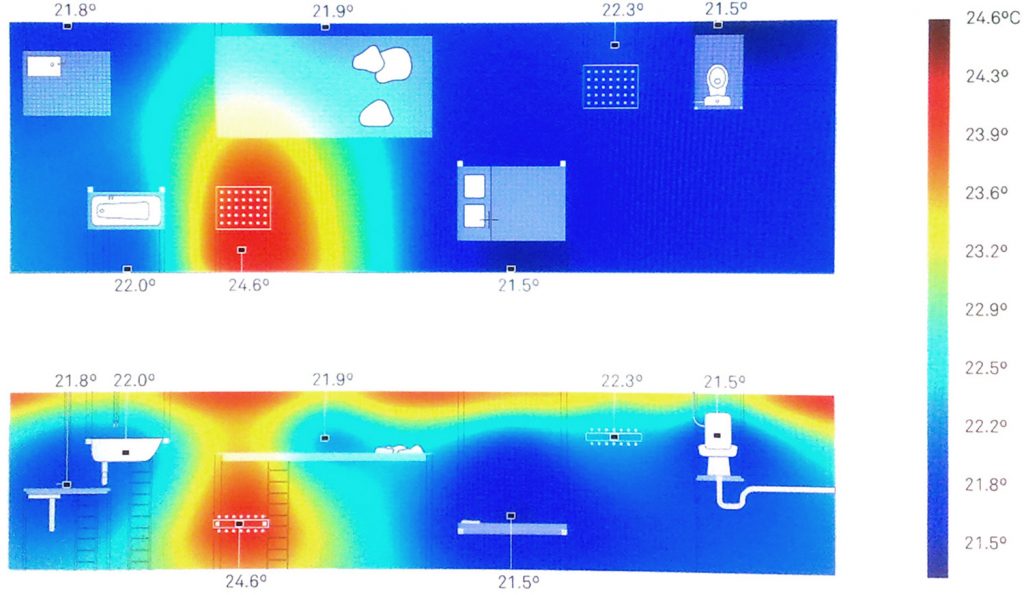

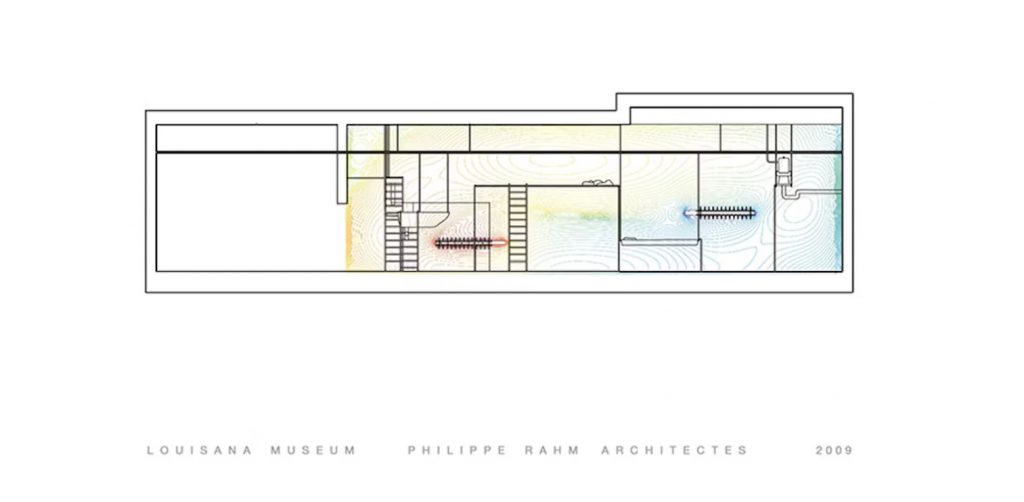

Like the sun, artificial lights produce heat because luminous electromagnetic radiation is energy itself. Paradoxically, electric “light” gives off more invisible heat than it does visible light. Depending upon the technique used, a larger or smaller part of the energy will be transformed into heat and another into light. The incandescent light bulbs used in domestic space throughout the 20th century have an output efficiency of light that is extremely weak since for one bulb of 100W, only two watts are transformed into light, while 98W stays invisible as pure heat. The more recent compact fluorescent light bulbs have a better output efficiency. For the same luminosity of a 100W incandescent bulb, one needs only a 20 W compact fluorescent, and of these 20 W, 6 W are converted into light, and only 14 W are lost in heat. Depending upon the choice of light bulb, a certain temperature of light is emitted: hotter for incandescent bulbs and colder for compact fluorescents. What one knows for certain is that the bulbs we use to light our interior spaces are, in reality, more a source of heat than of light; the relationship between heat and light is almost a minor collateral consequence of these energy sources. The reality of a collusion between heat and light becomes, in our project for the Louisiana Museum, the principal of a production in the interior of an atmosphere with its meteorology and its temporality. We propose in this way to heat the space of the Louisiana museum with only electric lights, in a fashion similar to that of the solar system where the source of heating, the sun, is combined with that of light. The space of the Louisiana Museum is 225 square meters. One can calculate that 5000W is necessary in order to heat the space correctly. We also propose to produce theses 5000 through two light sources arranged diagonally in the space, one incandescent, the other compact fluorescent. Thus, for each bulb, we produce 98 W on the incandescent side and 14 W on the compact fluorescent side, which is 112 W per pair. Thus, 45 incandescent light bulbs at 100W and 45 compact fluorescent light bulbs are needed to heat the space. Arranged diagonally in the space, programmed according to a thermostat set to a differential of 16 degrees Celsius for the high compact fluorescent radiator and 19 degrees Celsius for the incandescent source situated at the bottom of the space, this asymmetrical disposition provokes the formation of a thermal plug up high which permits the hotter heat below to spread out horizontally. An atmosphere and its meteorology are formed in this way, in which one occupies all the spatial and climatic dimensions between latitudes of luminous intensity and longitudes of temperature and color, altitudes of temperature. The thermostats provoke a luminous temporality by turning the lights off and on depending upon the temperatures measured, generating a true interior astronomy with its incandescent days and its compact fluorescent nights.

Al igual que el sol, las luces artificiales producen calor porque la radiación electromagnética luminosa es energía en sí misma. Paradójicamente, la “luz” eléctrica emite más calor invisible que la luz visible. Dependiendo de la técnica utilizada, una parte mayor o menor de la energía se transformará en calor y otra en luz. Las bombillas incandescentes utilizadas en el espacio doméstico a lo largo del siglo XX tienen una eficiencia de salida de luz extremadamente débil ya que por una bombilla de 100W, sólo dos vatios se transforman en luz, mientras que 98W permanecen invisibles como calor puro. Las bombillas fluorescentes compactas más recientes tienen una mejor eficiencia de salida. Para obtener la misma luminosidad de una bombilla incandescente de 100 W, sólo se necesita una fluorescente compacta de 20 W, y de estos 20 W, 6 W se convierten en luz y sólo 14 W se pierden en calor. Dependiendo de la bombilla elegida, se emite una determinada temperatura de luz: más caliente para las bombillas incandescentes y más fría para las fluorescentes compactas. Lo que sí sabemos con certeza es que las bombillas que utilizamos para iluminar nuestros espacios interiores son, en realidad, más una fuente de calor que de luz; la relación entre calor y luz es casi una consecuencia colateral menor de estas fuentes de energía. La realidad de una connivencia entre calor y luz se convierte, en nuestro proyecto para el Museo de Luisiana, en el principio de una producción en el interior de una atmósfera con su meteorología y su temporalidad. Proponemos de este modo calentar el espacio del museo de Luisiana únicamente con luz eléctrica, de forma similar al sistema solar donde la fuente de calefacción, el sol, se combina con la de la luz. El espacio del Museo Luisiana es de 225 metros cuadrados. Se puede calcular que se necesitan 5000W para calentar el espacio correctamente. También proponemos realizar estas 5000 a través de dos fuentes de luz dispuestas diagonalmente en el espacio, una incandescente y otra fluorescente compacta. Así, por cada bombilla producimos 98 W en el lado incandescente y 14 W en el lado fluorescente compacto, lo que equivale a 112 W por par. Así, para calentar el espacio se necesitan 45 bombillas incandescentes de 100W y 45 bombillas fluorescentes compactas. Dispuesta diagonalmente en el espacio, programada según un termostato regulado a un diferencial de 16 grados centígrados para el radiador fluorescente compacto de alta altura y de 19 grados centígrados para la fuente incandescente situada en el fondo del espacio, esta disposición asimétrica provoca la formación de una atmósfera térmica. enchufe en lo alto, lo que permite que el calor más caliente de abajo se extienda horizontalmente. De esta manera se forma una atmósfera y su meteorología, en la que se ocupan todas las dimensiones espaciales y climáticas entre latitudes de intensidad luminosa y longitudes de temperatura y color, altitudes de temperatura. Los termostatos provocan una temporalidad luminosa al apagar y encender las luces en función de las temperaturas medidas, generando una verdadera astronomía interior con sus días incandescentes y sus noches fluorescentes compactas.

Text and images via Philippe Rahm Architectes.