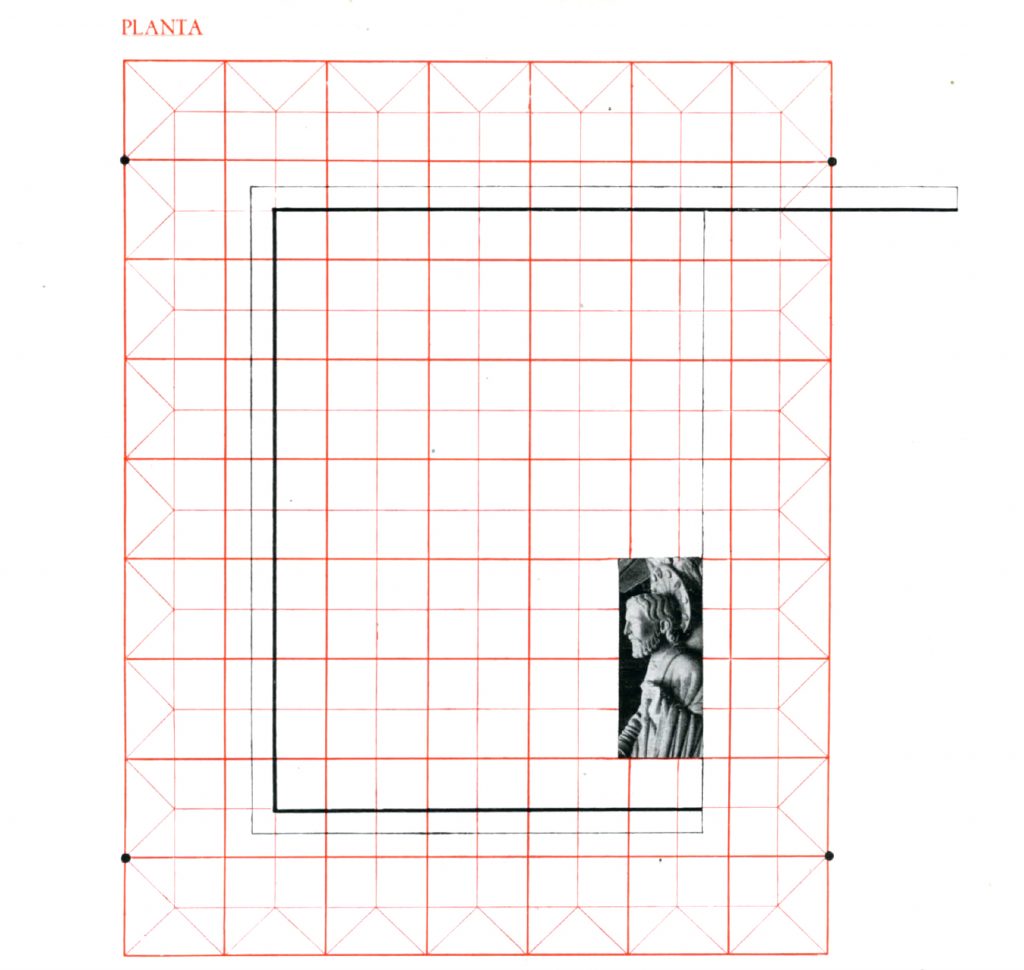

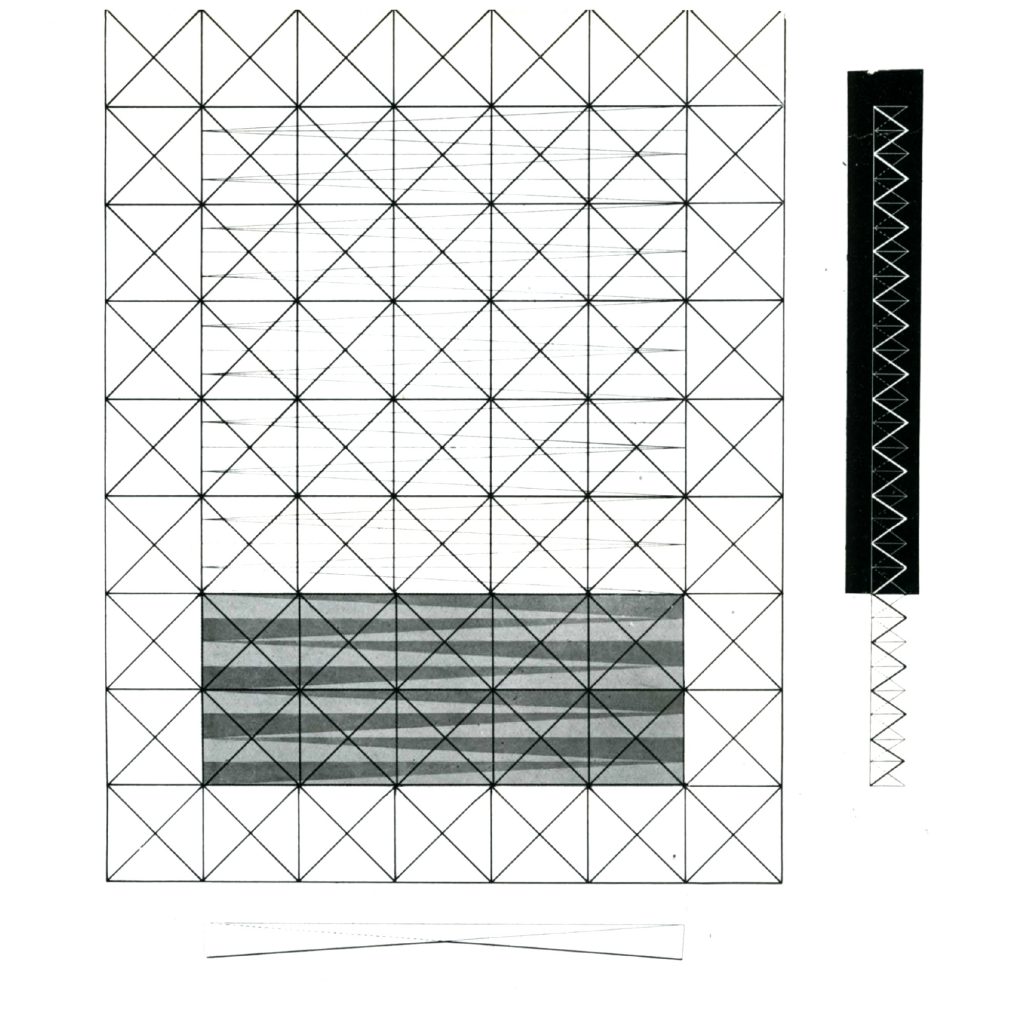

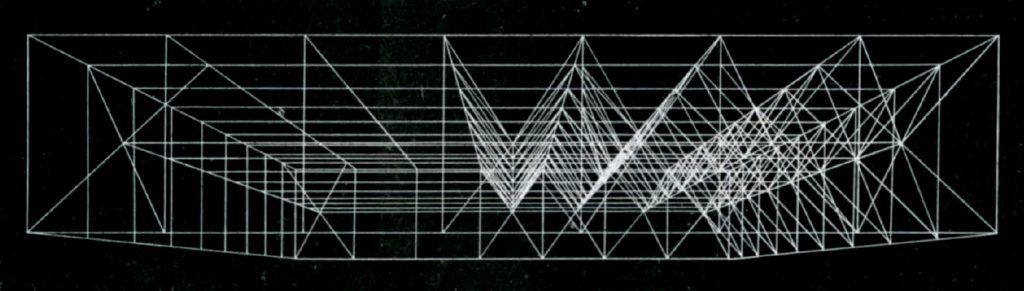

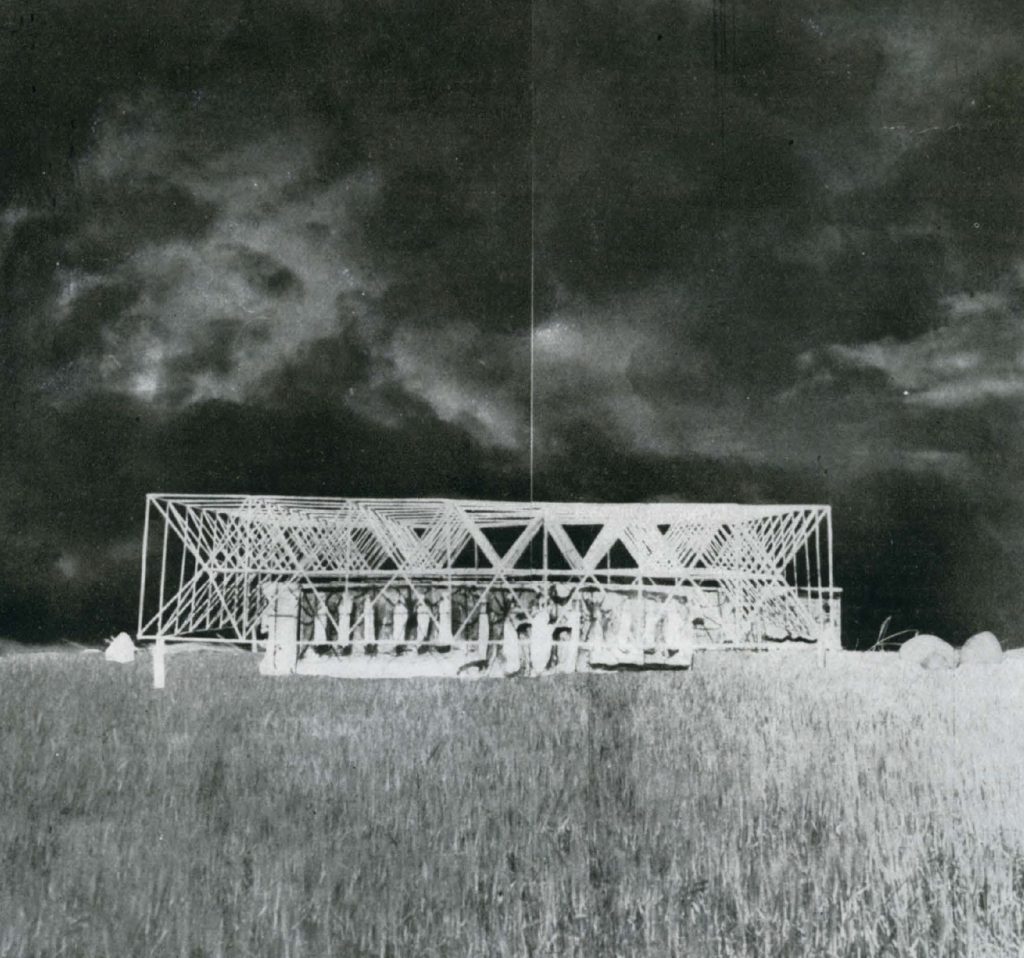

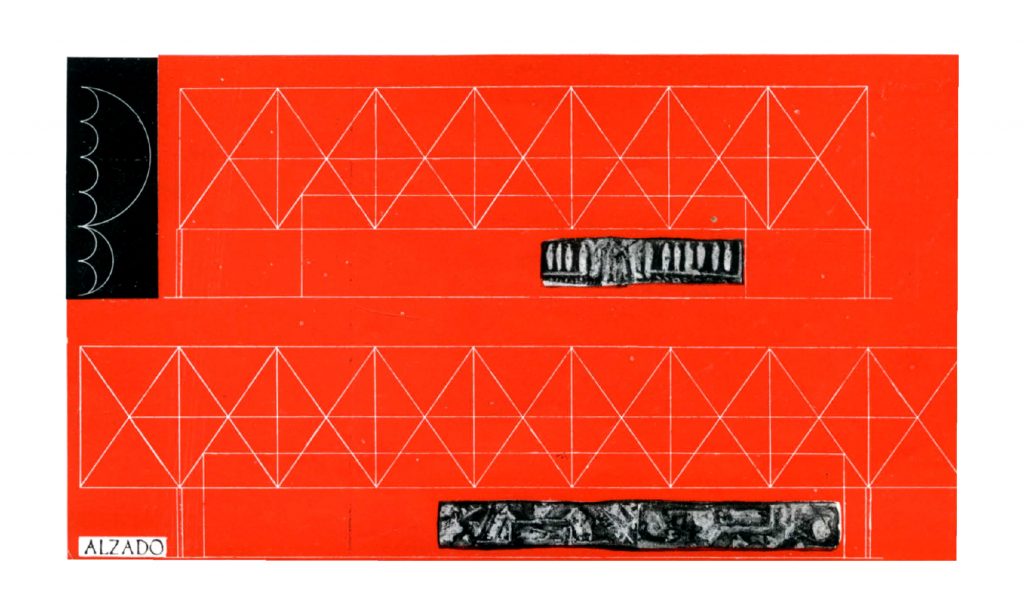

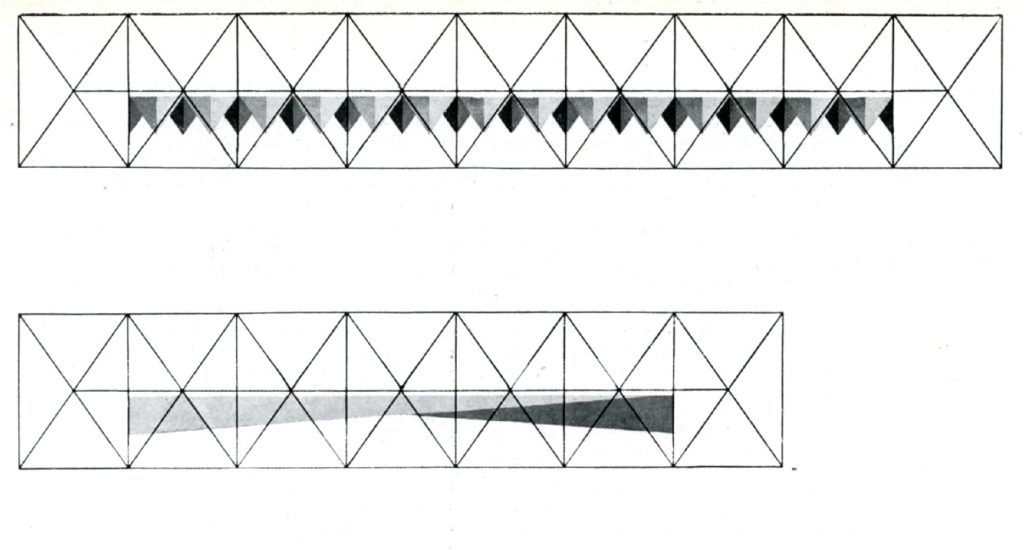

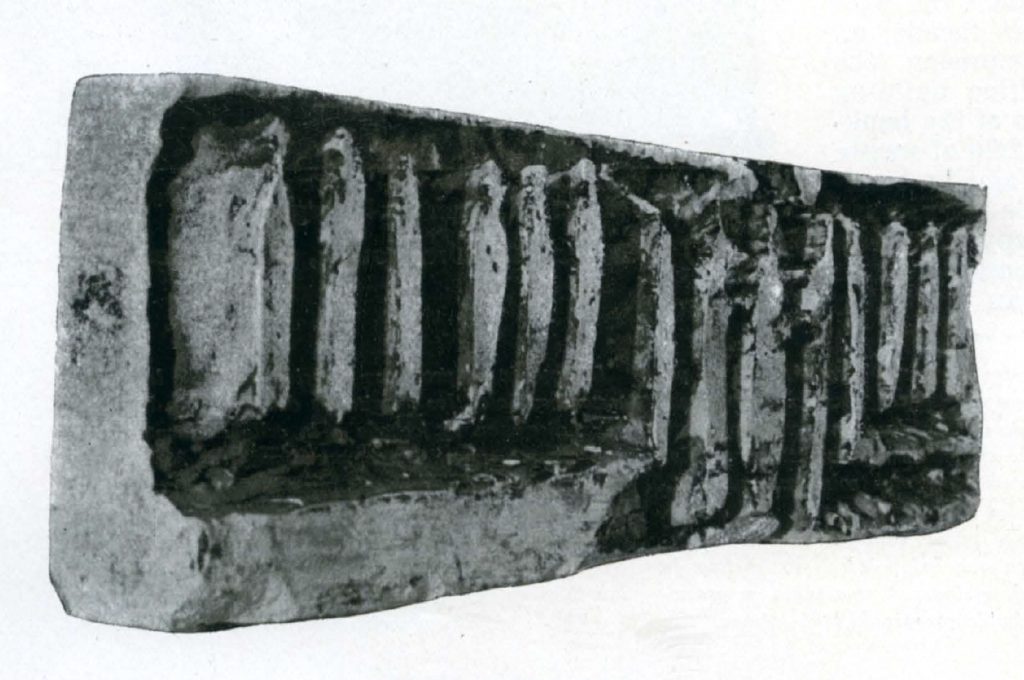

This project – actually just ideas – is, as you can see, a bit of fantasy thinking about a Competition for the National Architecture Prize, which tries (at least that’s what we think) to encourage new ideas about this art. Since we already started from its non-realization, we have idealized, a little by thinking and a little by materializing this thought, about what a chapel on the traditional pilgrimage route should be today. We have imagined it more like a humiliation than a chapel; something that in itself does not interrupt or stop the pilgrim, but, on the contrary, helps him to continue forward along this spiritual path-path under the stars that leads to the Apostle. In short, architecture is based on a spatial geometric structure formed by linear metallic elements, edges of an ideal polyhedral mesh, which, based on limited points of a floor, places in space a multiple network of fixed points, that can serve as support and support – better we would say suspension or support – for the cover, conceived as a light surface folded in a zigzag. Independent of structure and roof, and without touching the latter (since neither would be useful for one nor the other), a stone wall five meters high is arranged which, partially delimiting the interior enclosure, is, in turn, a place of development of a symbolic theme or legend of the Apostle, according to sketches by the sculptor Jorge de Oteiza. As a location we have imagined a promontory or hill in the middle of a field of ears. The brilliant shape of the temple will emerge as if on the crest of a wave in the sea of ears of the Castilian plateau. This brief explanation and the plans you see will guide you about our idea; But if it seems convenient, we will briefly explain some point that served as our foundation.

Este proyecto -en realidad sólo ideas- es, como puedes ver, un poco de fantasía pensando en un Concurso para el Premio Nacional de Arquitectura, que intenta (al menos eso creemos) fomentar nuevas ideas sobre este arte. Como ya partimos de su no realización, hemos idealizado, un poco pensando y un poco materializando este pensamiento, sobre lo que debería ser hoy una capilla en la ruta tradicional de peregrinación. La hemos imaginado más como un humilladero que como una capilla; algo que en sí mismo no interrumpe ni detiene al peregrino, sino que, por el contrario, le ayuda a seguir adelante por este camino-senda espiritual bajo las estrellas que conduce al Apóstol. En definitiva, la arquitectura se basa en una estructura geométrica espacial formada por elementos metálicos lineales, aristas de una malla poliédrica ideal, que, partiendo de los puntos limitados de un suelo, coloca en el espacio una red múltiple de puntos fijos, que pueden servir de soporte y apoyo -mejor diríamos suspensión o soporte- a la cubierta, concebida como una superficie ligera plegada en zigzag. Independiente de estructura y cubierta, y sin tocar esta última (pues ni una ni otra servirían), se dispone un muro de piedra de cinco metros de altura que, delimitando parcialmente el recinto interior, es, a su vez, lugar de desarrollo de un tema simbólico o leyenda del Apóstol, según bocetos del escultor Jorge de Oteiza. Como emplazamiento hemos imaginado un promontorio o colina en medio de un campo de espigas. La forma brillante del templo emergerá como en la cresta de una ola en el mar de espigas de la meseta castellana. Esta breve explicación y los planos que ves te orientarán sobre nuestra idea; Pero si te parece conveniente, explicaremos brevemente algún punto que nos sirvió de fundamento.

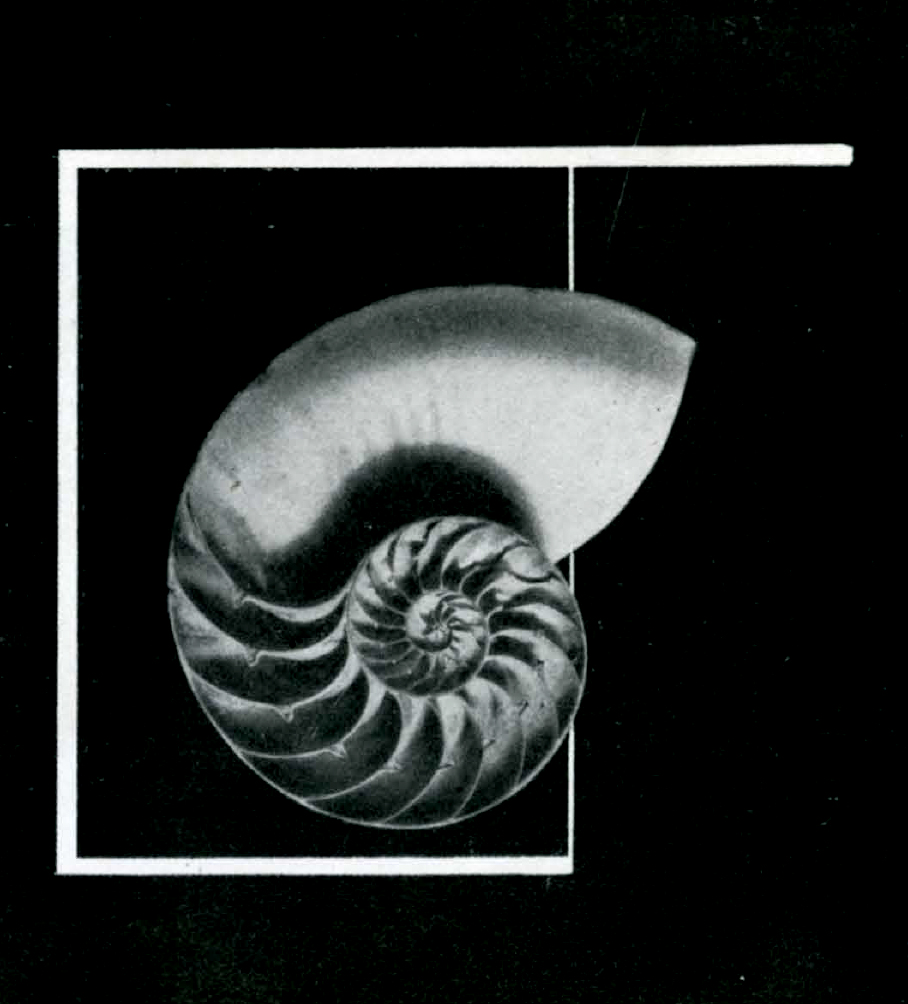

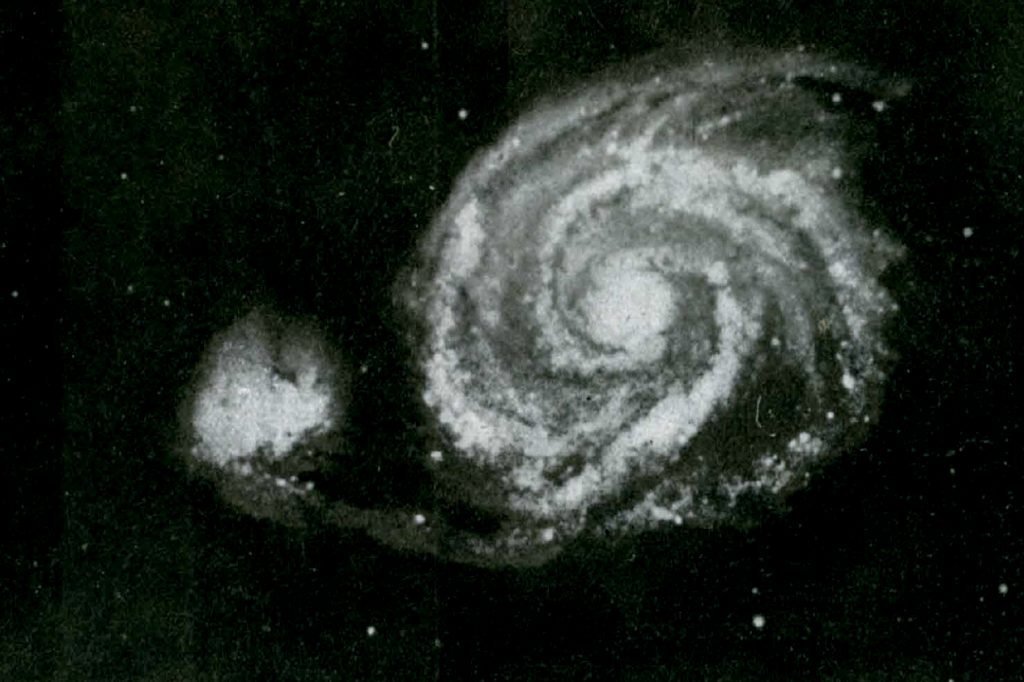

The problem of the temple is, and has always been, of capital importance for architecture. History shows us that the newest, most daring and audacious forms have always been used. If each of them were a temple, a religious building, it was because in them the architect, artist, knew how to infuse them with a high transcendent meaning. If it is possible to speak of religious treatment of a form of art, it is not possible, however, to say that a structure is religious in itself or not. If it is, it is-we repeat-because in his use the artist instilled in it that superior seal. In this hypothesis, it will be understood that we have had no problem resorting to the most audacious, most advanced forms, most in accordance with the means and tools of our industry and our culture: neither churches of baked clay, stone or wood ; new churches, with new materials, which, artificial today in their first uses, will soon become means as natural as those that were directly offered to primitive man on the landscape of his days. Should we renounce them because, being natural in themselves, they have emerged from Nature through a tool greater than the primitive flint ax with which primitive man carved stone, and which we call industry today? modern? We are interested in stating the attraction of these first attempts at spatial structure. In itself, the fact of a three-dimensional approach seems to us a priori more perfect than any flat resolution, the ideal only as a particularization of the general formula to specific cases. The innate agoraphobia of the human being has always led to a reduced vision of things, in spaces of smaller dimensions, flat spaces, which then, better known, go on to pose without limitation in their true spatial reality. The lintel, the arch, is resolved first; then, over time, the vault.

El problema del templo es, y ha sido siempre, de capital importancia para la arquitectura. La historia nos muestra que siempre se han utilizado las formas más novedosas, atrevidas y audaces. Si cada una de ellas fue un templo, un edificio religioso, fue porque en ellas el arquitecto, el artista, supo infundirles un alto significado trascendente. Si es posible hablar de tratamiento religioso de una forma de arte, no es posible, sin embargo, decir que una estructura es religiosa en sí misma o no. Si lo es, lo es -repetimos- porque en su uso el artista le infundió ese sello superior. En esta hipótesis, se comprenderá que no hayamos tenido inconveniente en recurrir a las formas más audaces, más avanzadas, más acordes con los medios y herramientas de nuestra industria y nuestra cultura: ni iglesias de barro cocido, piedra o madera ; iglesias nuevas, con materiales nuevos, que, artificiales hoy en sus primeros usos, pronto se convertirán en medios tan naturales como los que se ofrecían directamente al hombre primitivo en el paisaje de sus días. ¿Debemos renunciar a ellos porque, siendo naturales en sí mismos, han surgido de la Naturaleza a través de una herramienta mayor que la primitiva hacha de sílex con la que el hombre primitivo tallaba la piedra, y que hoy llamamos industria? moderna? Nos interesa constatar el atractivo de estos primeros intentos de estructuración espacial. En sí mismo, el hecho de una aproximación tridimensional nos parece a priori más perfecto que cualquier resolución plana, lo ideal sólo como particularización de la fórmula general a casos concretos. La agorafobia innata del ser humano ha conducido siempre a una visión reducida de las cosas, en espacios de dimensiones menores, espacios planos, que luego, mejor dicho, pasan a plantearse sin limitación en su verdadera realidad espacial. Primero se resuelve el dintel, el arco; luego, con el tiempo, la bóveda.

In other arts, such as painting, for example, man seeks, in the first stages of culture, the flat vision, the representation of silhouette, which later, having mastered perspective, he converts into three-dimensional, even within the only two dimensions of the painting in which it moves. Spatial metallic forms are not at all common, even less so in temple architecture; But having already begun the path in the industrial field, we have not hesitated to apply it to the highest architecture. And we hope that the future, based on this geometry of polyhedra in space, will be able to extract from the new element possibilities of beauty no less than those achieved in the architectures of the past with other similar forms of wood or stone. The new shape (of aluminum tube) is not ours; of being our something is the attempt of its application, as a structure, in the solution of the temple. The result is still crude, primitive, rudimentary. If we worked on it again, we could extract – who doubts it! – new suggestions. The first, which we already sense, is that of a new sense of rhythm, compared to the classic constant module of the Greek arrangement – equal loads for equal columns, with also equal modules; a new dynamic rhythm, which would emerge simply by trying to achieve an equal distribution of efforts on equally equal sections of bars in the current hypothesis, from a certain support situation. This modular rhythm, closer to the plot of a spectrum than to the monotony of divisions of a double decime. Furthermore, it would be, we have no doubt, one of the first modifications that we would introduce for the best solution to the initial structure.

En otras artes, como la pintura, por ejemplo, el hombre busca, en los primeros estadios de la cultura, la visión plana, la representación de la silueta, que más tarde, dominada la perspectiva, convierte en tridimensional, incluso dentro de las dos únicas dimensiones del cuadro en que se mueve. Las formas espaciales metálicas no son nada comunes, y menos aún en la arquitectura de los templos; pero habiendo iniciado ya el camino en el ámbito industrial, no hemos dudado en aplicarlo a la arquitectura más elevada. Y esperamos que el futuro, basándose en esta geometría de poliedros en el espacio, pueda extraer del nuevo elemento posibilidades de belleza no menores que las logradas en las arquitecturas del pasado con otras formas similares de madera o piedra. La nueva forma (de tubo de aluminio) no es nuestra; de ser nuestro algo es el intento de su aplicación, como estructura, en la solución del templo. El resultado sigue siendo tosco, primitivo, rudimentario. Si volviéramos a trabajar en él, podríamos extraer -¡quién lo duda! – nuevas sugerencias. La primera, que ya intuimos, es la de un nuevo sentido del ritmo, frente al clásico módulo constante de la disposición griega -cargas iguales para columnas iguales, con módulos también iguales-; un nuevo ritmo dinámico, que surgiría simplemente al intentar conseguir una distribución igual de esfuerzos sobre tramos de barras igualmente iguales en la hipótesis actual, a partir de una determinada situación de apoyo. Este ritmo modular, más cercano a la trama de un espectro que a la monotonía de divisiones de un doble decimal. Además, sería, no nos cabe duda, una de las primeras modificaciones que introduciríamos para la mejor solución de la estructura inicial.

Should we use stone today to build the temple? The evolution of science and human knowledge tell us about the evolution of the sense of mass and heaviness as synonymous with the idea of force and energy. By establishing a parallel between heavy masses, as a representation of force in the ancient world, the ox cart transporting a stone, the great pyramid as a background, and the new idea of energy, now independent of gravitational mass. -the high- tension pole, we would think to ask: Where is the structure of today’s new building, which links, like the oxcart yesterday, with the pyramid; the high voltage pole, with the new temple? What is the equivalent structure to the stone temple of yesterday? of the church today? The problem of the new temple must find its solution in the answer to these new questions, if today’s architecture is to be, as yesterday’s always was, faithful to the knowledge, the materials, the changes of scene. and atmosphere of its century. Faced with these questions, putting a cross or a bell so that the new building looks like a temple seemed to us a mere figurative concession, a convenience in avoiding the definitive solution to the problem by taking the easy route. We repeat: these are, in summary, our ideas and the first materialization in the form of a solution. Naturally, a chapel or humiliation not to carry out, but to serve as a support and starting point for a more serious study, if one wants to reach this path – something that we still do not know if a real goal will be reached.

¿Deberíamos utilizar hoy la piedra para construir el templo? La evolución de la ciencia y el conocimiento humano nos hablan de la evolución del sentido de la masa y la pesadez como sinónimos de la idea de fuerza y energía. Estableciendo un paralelismo entre las masas pesadas, como representación de la fuerza en el mundo antiguo, el carro de bueyes transportando una piedra, la gran pirámide como telón de fondo, y la nueva idea de energía, ahora independiente de la masa gravitatoria. -el poste de alta tensión, se nos ocurriría preguntar: ¿Dónde está la estructura del nuevo edificio de hoy, que enlaza, como la carreta de bueyes ayer, con la pirámide; el poste de alta poste de alta tensión, con el nuevo templo? ¿Cuál es la estructura equivalente al templo de piedra de ayer? ¿de la iglesia de hoy? El problema del nuevo templo debe encontrar su solución en la respuesta a estas nuevas preguntas, si la arquitectura de hoy arquitectura de hoy ha de ser, como lo fue siempre la de ayer, fiel a los conocimientos, los materiales, los cambios de escenario y ambiente de su siglo. Ante estas preguntas, poner una cruz o una campana para que el nuevo edificio parezca un templo nos parecía para nosotros una mera concesión figurativa, una conveniencia para evitar la solución definitiva del problema tomando tomando el camino fácil. Repetimos: éstas son, en resumen, nuestras ideas y la primera materialización en forma de solución. Naturalmente, una capilla o humillación no para llevarla a cabo, sino para servir de apoyo y punto de partida para un estudio más serio estudio, si se quiere llegar a este camino -algo que todavía no sabemos si se alcanzará una meta real.

Text by F. Javier Saénz de Oiza. Via Revista Arquitectura n°161, 1955