INTERVIEW IN ENGLISH (Entrevista en español más abajo)

“Peter Blake: And when architects try to organize it or give it some kind of form, they seem to ruin it.

Paul Rudolph: We have certain limitations as architects. That is part of what I mean by “spirit”. It is the corrective factor of human intelligence, in all fields.

PB: So there we have it: site, scale, structure, function, and spirit. Have you noticed every time you talk about one of those things, you seem to touch upon or refer to Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion in one way or another? Why is that?

PR: To me, the Barcelona Pavilion is Mies’ greatest building. It is one of the most human buildings I can think of -a rarity in the twentieth century. It is really fascinating to me to see the tentative nature of the Barcelona Pavilion. I am glad that Mies really wasn’t able to make up his mind about a lot of things – alignments in the marble panels, or the mullions, or the joints in the paving. Nothing quite lines up, all for very good reasons. It really humanizes the building.

PB: My guess is if he had had a chance to redesign it about twenty years later, he might have messed it up – made it too regular, aligned everything…

PR: Possibly. The courtyards and the interior space cast a spell on you which you will remember forever.

PB: If you were to put your finger on it, what do you think you learned from the Barcelona Pavilion?

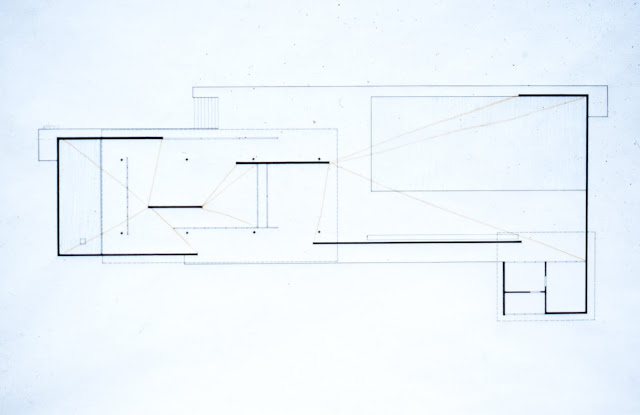

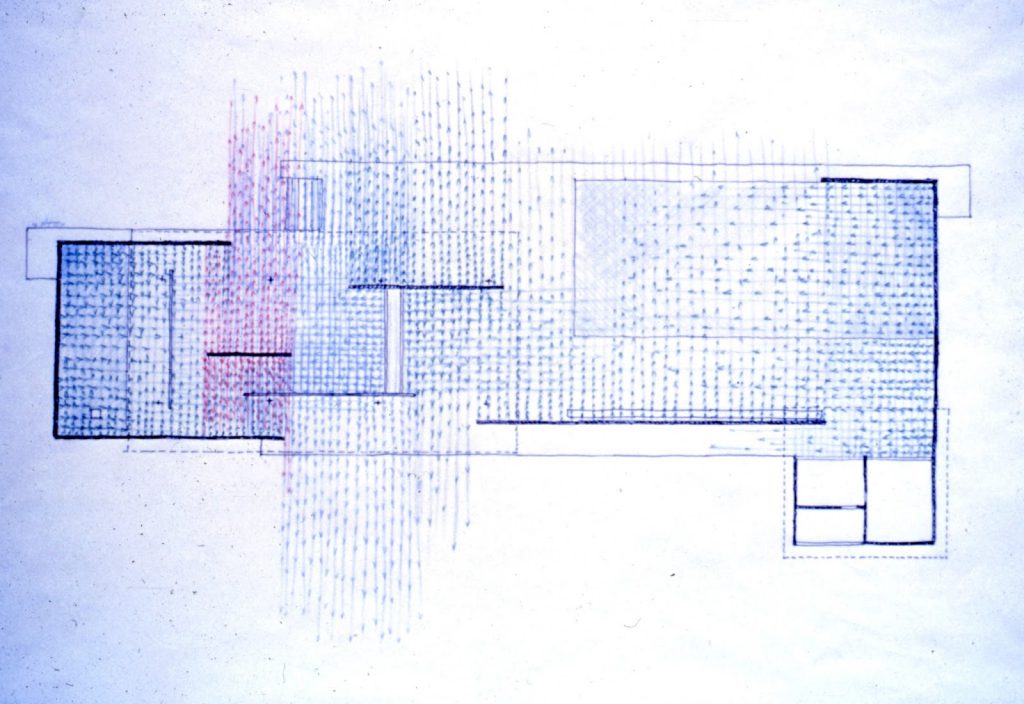

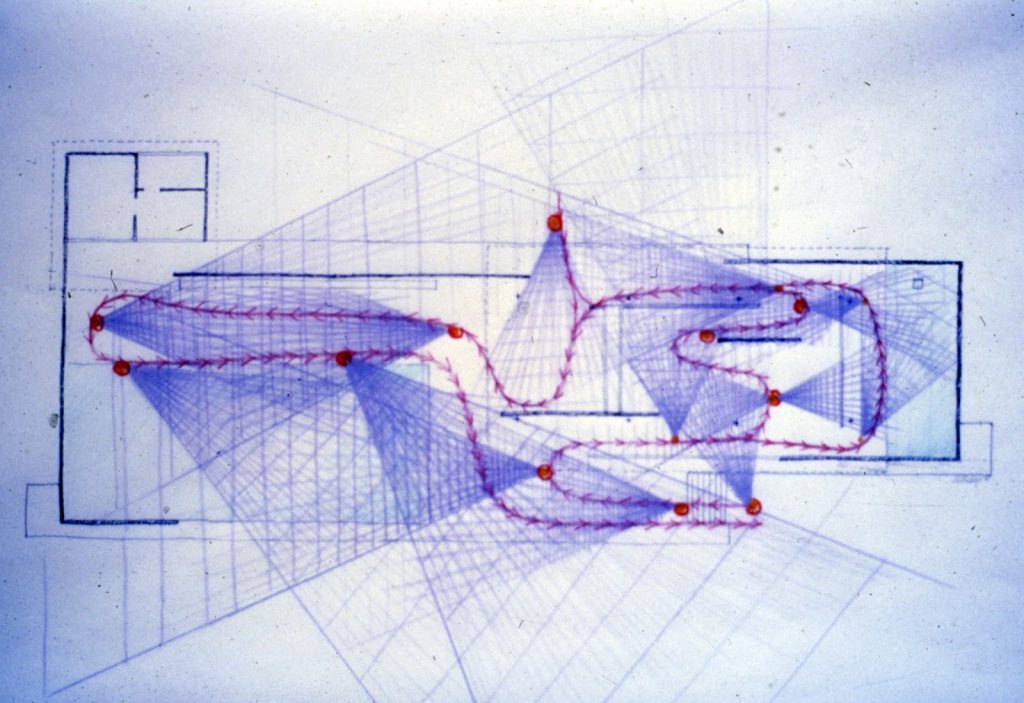

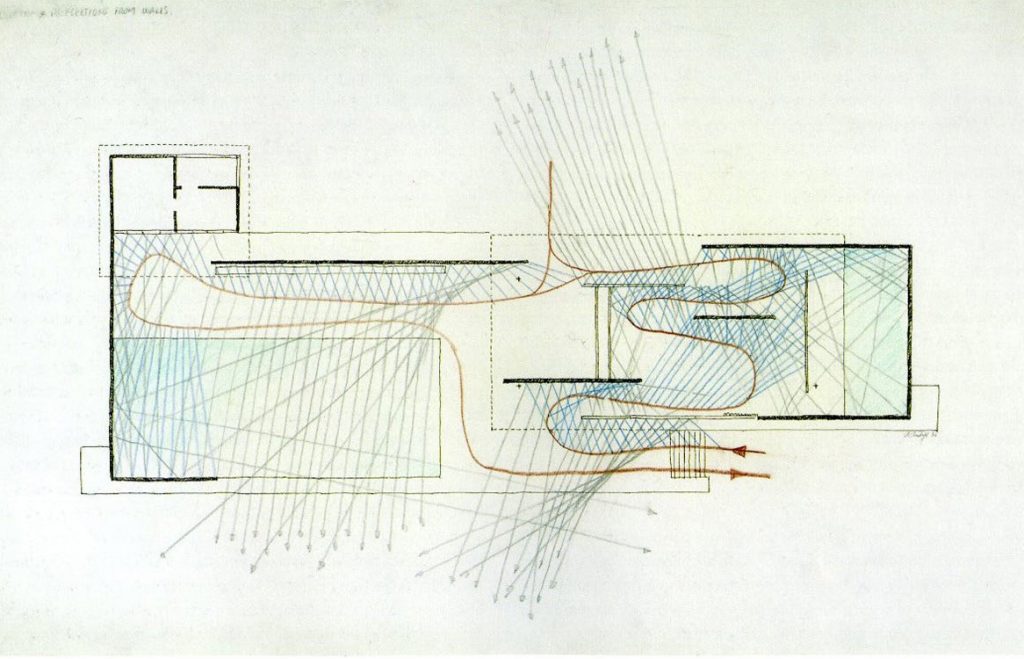

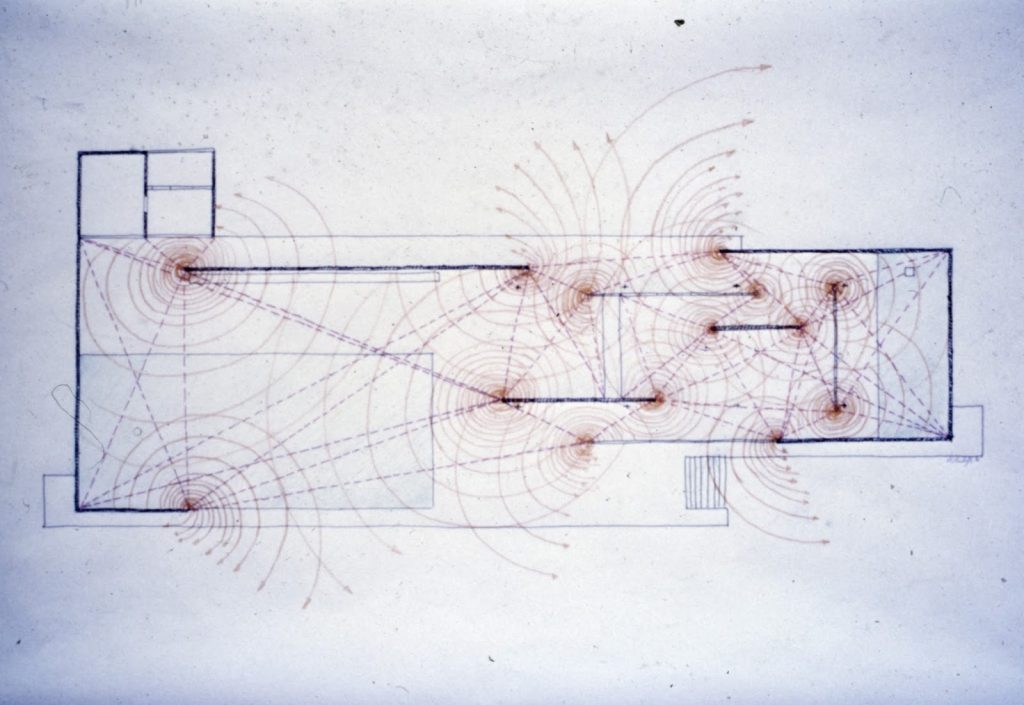

PR: I made a few sketches that are meant to illustrate the impact of the actual building (as rebuilt in 1992 on the same site as the original 1929 Pavilion), which is very different from drawings, photos, etc. The Barcelona Pavilion is religious in its nature and is primarily a spatial experience. We have no accepted way of indicating space, and therefore the sketches made are very inadequate. One is drawn by the sequence of space through it. Multiple reflections of the twentieth century modify the architecture of light and unprecedented in architecture and the greatest of all of Mies’ buildings.

PB: Your first drawing is a series of diagrams showing the circulation through the building. On the east is the more familiar entrance, used by the general public; on the west is the entrance for the King and Queen of Spain and used by other dignitaries at the time of the opening.

PR: Yes. The circulation from the east leads you up a flight of steps that leads to the platform on which the PAVILION STANDS. The flight of stairs is spatially compressed, and when you reach the top of the platform, the pool causes you to turn 180 degrees. This turn prepares you for the compressed entry with a glass wall on the right and the green. Tinian marble wall on the left, all modified by reflected trees. This squeezed space leads directly into the larger dominating space that contains the major function of the Pavilion. This flow of space continues all the way through the building in a highly disciplined way; nothing is left to chance. In my diagram the compressed space, the liberated space, the movement of space diagonally, vertically, and curved space modify the rectangular plan in a very clear and surprising fashion. The space is revealed but also hidden. The density of space is greater as it approaches the defining planes that form the Pavilion. The inward pull to the defining planes is offset by the reflective surfaces, so that most of the surfaces vibrate. I have tried to define the essential fluidity of these spaces and the interconnection of the inside and the outside. This highly disciplined flow of space is all-pervasive a natural constriction and release of space that leads you on everything is in motion, and you are carried along almost by unseen felt forces.”

Extract of the interview to Paul Rudolph by the architect Peter Blake published in the Book ‘Paul Rudolph: The Late Work”.

ENTREVISTA EN ESPAÑOL

“Peter Blake: Porque cuando los arquitectos tratan de organizar el espacio o darle una forma precisa, parece que lo acaban destrozando.

Paul Rudolph: Como arquitectos tenemos ciertas limitaciones, que es a lo que yo llamo “espíritu”. Es el corrector de los factores humanos, en todos los campos.

PB: Entonces ahí lo tenemos: lugar, escala estructura, función, y espíritu. ¿Se da cuenta que cada vez que habla de alguno de estos temas, parece que se está refiriendo al Pabellón de Barcelona de Mies Van der Rohe de una forma u otra? ¿A qué cree que se debe?

PR: Para mí, el Pabellón de Barcelona de Mies es su mejor edificio. Es uno de los proyectos más humanos de los que se me ocurren – una rarea del siglo XX. Es realmente fascinante ver la naturaleza de este pabellón. Me alegra ver que Mies no fue capaz de resolver ciertos aspectos de este proyecto tales como la modulación de los mármoles, los montantes o las juntas del pavimento. Nada realmente está alineado por una buena razón. Es lo que realmente humaniza el edificio.

PB: Supongo que si tuviera la oportunidad de rediseñarlo veinte años más tarde, tal vez lo hubiese arruinado haciéndolo especialmente regulado, modulando todo…

PR: Posiblemente. La relación entre los patios y el espacio interior crear un magia que es difícil de olvidar.

PB: Si tuvieses que resaltar algo específico, ¿Qué crees que has aprendido del Pabellón de Barcelona?

PR: Realicé una series de dibujos que pretendían ilustrar el impacto del actual edificio (construido en 1992 en el lugar original que se construyó en 1929), los cuales difieren de otros dibujos de otros dibujos, fotografías, etc. El pabellón de Barcelona es principalmente una experiencia espacial. No hemos alcanzado una forma de describir el espacio, y por tanto los dibujos se hacen inadecuados. Uno de ellos traza la secuencia del espacio a través del pabellón.

PB: Tu primer dibujo es una serie de diagramas que muestran la circulación a través del pabellón. Al este está la entrada más familiar, usada por el público en general; al contrario por el oeste está la entrada para los reyes de España y otros mandatarios de la época en el que fue inaugurado.

PR: Sí, la circulación desde el este te dirige desde la escalera hacia la plataforma desde donde el pabellón se asienta. El ancho de los escalones es espacialmente comprimido y cuando uno alcanza la plataforma, la piscina te obliga a girar 180 grados. Este giro te prepara para la estrecha entrada con un muro de vidrio a la derecha y el jardín; el mármol verde antiguo de Grecia. se modifica por el reflejo de los árboles. Este espacio apretado conduce directamente al espacio dominante, más grande, que contiene la función principal del pabellón. Esta circulación espacial continúa por todo el edificio con una gran disciplina, nada es dejado al azar. En mi diagrama, el espacio angosto, el espacio más amplio, el movimiento diagonal y vertical modifican la planta regular de un modo muy claro y sorprendente. El espacio aparece pero también se esconde y la densidad del espacio fabulosa ya que consigue definir los planos que dan forma al pabellón. Los muros interiores se desvanecen debido a las superficies reflejadas creando una equidistancia en los límites lo cual provoca que las superficies vibren. He tratado de definir la fluidez esencial de tales espacios así como la conexión entre el exterior e interior. Esta circulación tan disciplinada del espacio que lo oprime y lo libera provoca un movimiento continuo que te transporta de una forma casi imperceptible.”

Extracto de la entrevista del arquitecto Peter Blake a Paul Rudolph publicada en el libro ‘Paul Rudolph: The Late Work”.

In 1986, six years before the Barcelona Pavilion was rebuilt, Paul Rudolph did a series of analytical drawings in plan where he attempts to define its spatial features. Rudolph tried to understand Mies’ Pavilion through its circulation, views and spatial and compositional elements. However, as he recognized in another extract of the previous interview, his drawings were inadequate. Rudolph thought that the quality of the pavilion was based on its rectangular and axial composition. However, when he later visited it, he realized that the flow among the spaces was greater than expected. For Rudolph the columns lose their presence whereas the large marble pieces mainly define the space because they are located as if they were paintings in the space.

En 1986, seis años antes de que el Pabellón de Barcelona fuera reconstruido, Paul Rudolph realiza una serie de dibujos analíticos en planta en donde trata de describir su espacialidad. Dichos dibujos intentan entender el proyecto de Mies a través de varios sistemas circulatorios, puntos de vista y elementos compositivos. Sin embargo, el propio Paul Rudolph reconocería más tarde en otro extracto de la entrevista publicada anteriormente que sus dibujos eran inadecuados. Rudolph pensaba que el Pabellón se componía mediante una serie de rectángulos y ejes axiales pero al visitarlo, descubrió que su fluidez era mayor de lo esperado. Para Rudolph las columnas pierden presencia en la realidad mientras que los grandes muros de mármol son los que definen el propio pabellón al estar colocadas como grandes pinturas en el espacio.