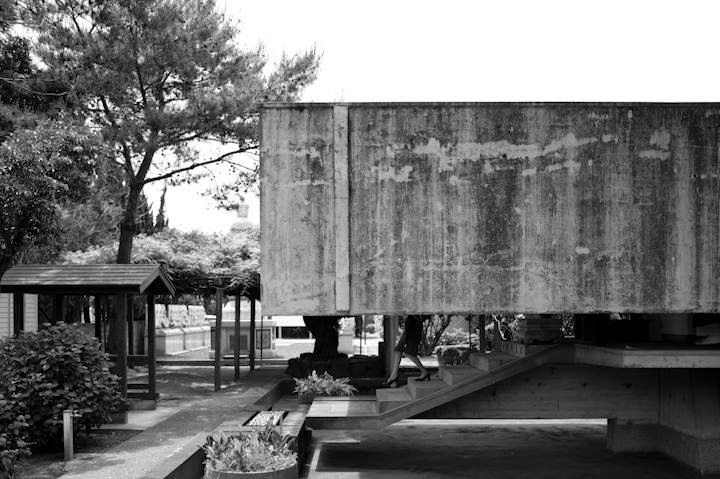

“In thee temples of Japan, a roof of heavy tiles is first laid out, and in the deep, spacious shadows creates by the eaves the rest of the structure is built. Nor is this true only of temples; in the palaces of the nobility and the houses of the common people, what first strikes the eye is the massive roof of tile or thatch and the heavy darkness that hangs beneath the eaves. Even at midday cavernous darkness spreads over all beneath the roof’s edge, making entryway, doors, walls, and pillars all but invisible. The grand temples of Kyoto, Chion’in, Honganji, and the farmhouses of the remote countryside are alike in this respect: like most buildings of the past their roofs give the impression of possessing far greater weight, height, and surface than all that stands beneath the eaves.”

Junichiro Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows.

“En los monumentos religiosos de nuestro país, los edificios quedan aplastados bajo las enormes tejas cimeras y su estructura desaparece por completo en la sombra profunda y vasta que proyectan los aleros. Visto desde fuera, y esto no sólo es válido para los templos sino también para los palacios y las residencias de la gente del pueblo, lo primero que llama la atención es la inmensa cubierta y la densa sombra que reina bajo el alero. Tan densa, que a veces en pleno día, en las tinieblas cavernosas que se extienden más allá del alero, apenas se distingue la entrada, las puertas, los tabiques o los pilares. En la mayoría de los edificios antiguos, y lo mismo sucede con las imponentes construcciones como el Chion’in o los Honganji, así como con cualquier tipo de granja perdida en la profundidad del campo, si se compara la parte inferior, debajo del alero, con la cubierta que la corona, se tiene la impresión, al menos visual, de que la parte más maciza, la más alta y extensa es la cubierta.”

Junichiro Tanizaki, El Elogio de la Sombra