‘Don’t Amputate-Renovate’ is a series curated by Hidden Architecture where we conduct a work of recovering and archiving of buildings demolished in New York before the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in April 1965 after the demolition of the Pennsylvania station. The archivist work of this series attempts to show a critical position against new possible acts of vandalism against the architectural heritage in the rest of the world. The name ´Don’t Amputates-Renovate´ is a tribute to the rallies realized in the 1960s attempting to stop the demolition of the typical train station. All the articles of this series have the same narrative organization: location, the historical context during its construction, architectural qualities of the building, demolition, and current situation of the site.

‘Don’t Amputate-Renovate’es una serie comisariada por Hidden Architecture donde realizamos un trabajo de recuperación y archivo de los edificios demolidos en Nueva York antes de la creación de la Comisión para la Preservación de Monumentos Históricos de Nueva York en Abril de 1965 tras la demolición de la estación de Pensilvania.. La labor archivista de esta serie es mostrar una posición crítica frente a probables nuevos actos de vandalismo contra el patrimonio arquitectónico en el resto del mundo. El nombre ‘Don’t Amputate-Renovate’ (No Amputes – Reueva) proviene de las manifestaciones que se realizaron para evitar la demolición de la mítica estación de trenes. Todos los artículos de la serie tendrán la misma organización narrativa: localización, contexto histórico en su construcción, cualidades arquitectónicas del edificio, demolición y estado actual de lugar.

*** Demolished (1963) ***

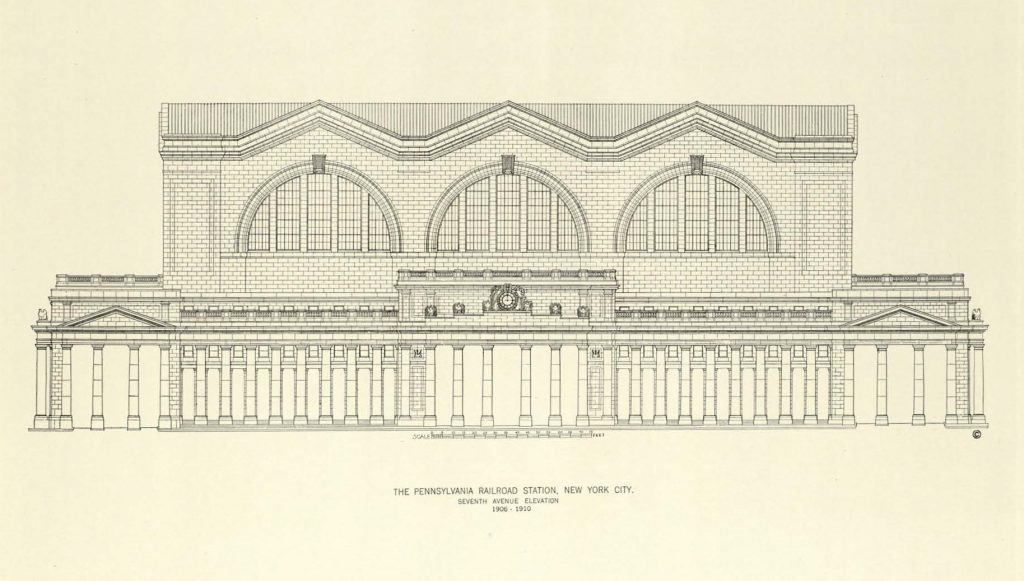

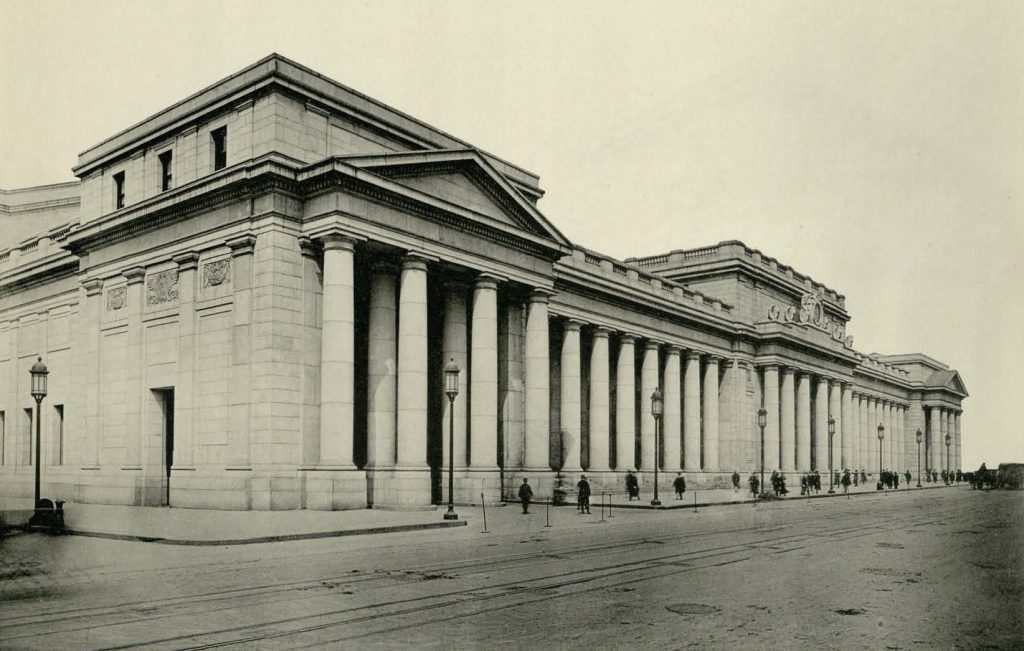

Penn Station was a critical project for the railroad development on the East Coast of the United States and its relation to the city of New York. The building, built between 1906 and 1910, was designed by the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White. This firm did some of the most important government and cultural buildings in the United States, such as the Municipal Building in New York or the Beaux-Arts Museum in Minneapolis. The Beaux-Arts Style profoundly influenced their work. The great crisis of the railroad industry after World War II in the US, the endless greed of several real estate developers, and the lack of regulations and control of the city hall ended up the building to be demolished between 1963 and 1968. The architectural and historical value of this project was similar to Grand Central Station.

La estación de Pensilvania fue un proyecto clave para el desarrollo del ferrocarril en la Costa Este de Estados Unidos y su relación con la ciudad de Nueva York. El edificio, construido entre 1906 y 1910, fue obra de los de arquitectos McKim, Mead & White. Esta firma de arquitectura realizó algunos de los edificios gubernamentales y culturales más importantes de Estados Unidos como el Edificio Municipal de Nueva York o el Museo de Bellas Artes de Minneapolis, con un estilo Beaux Arts. La gran crisis del ferrocarril que comenzó en Estados Unidos tras el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, unida una codicia desmesurada de varios promotores inmobiliarios, y la falta de control regulatorio por parte del ayuntamiento provocó que el edificio fuera finalmente demolido entre 1963 y 1968 perdiéndose un proyecto con un valor arquitectónico e histórico similar, o incluso superior, a la propia Estación de Grand Central.

LOCATION | LOCALIZACIÓN

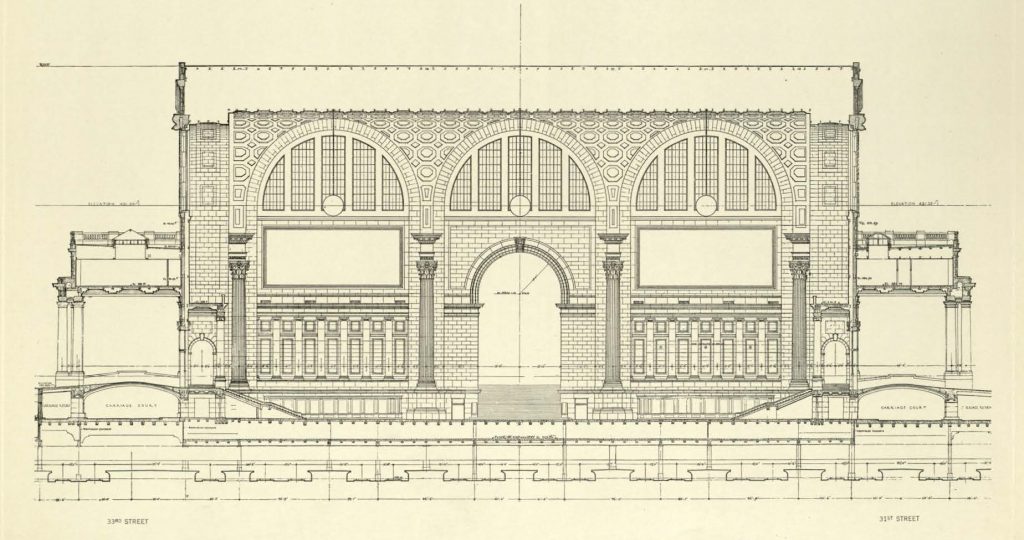

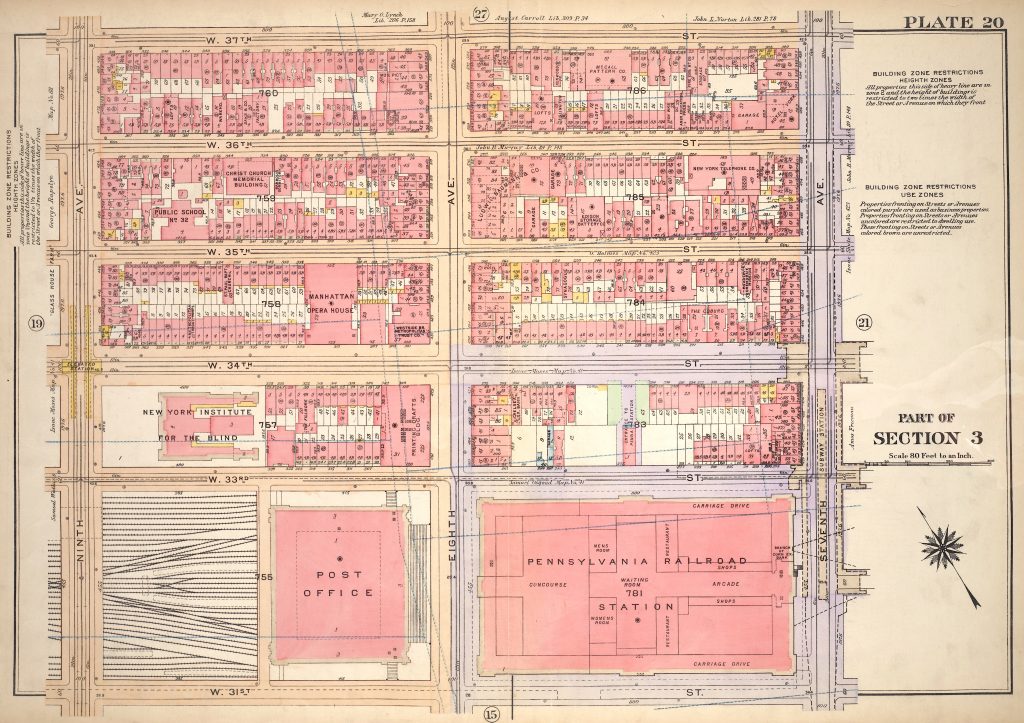

The building was located between Seventh and Eighth avenues and the streets 31st and 33rd, using two full blocks. Its location, strategically chosen, was close enough to the Hudson River – connecting the train lines that came from Pennsylvania and New Jersey – and the Midtown Manhattan. This condition also turned the building into an urban threshold within the city. From its construction until its demolition, Seventh avenue was the limit between the office area of midtown. Once you passed this avenue, the urban density decreased, and the city had an industrial character, including the river piers. The construction of the station and the yards used to regulate the train traffic under the Hudson Tunnel emphasized this double urban condition to both sides of the station. In 1913, the architect McKim Mead & White designed and built the Post Office in the west plot of the station, pushing the urban threshold one avenue towards the west.

El edificio estaba ubicado entre las avenidas Séptima y Octava y las calles 31 y 33, ocupando dos manzanas completas. Su localización, estratégicamente elegida, situaba la estación lo suficientemente cerca del Río Hudson para conectar con las líneas de tren que provenían de Pensilvania y New Jersey y, al mismo tiempo, en una posición casi central del Midtwon de Manhattan. Esto también provocó que se convirtiera desde el punto de vista urbano en un umbral dentro de la ciudad. Desde prácticamente su inauguración hasta su demolición en 1963, la séptima avenida era el límite de la zona de oficinas del midtown. Una vez pasada la avenida, la densidad urbana descendía y la ciudad adquiría un carácter industrial entre los que destacaban los embarcaderos. La construcción de la estación y los consecuentes patios construidos al descubierto para regular el tráfico del túnel bajo el río Hudson intensificaban esta doble condición urbana a ambos lados de la estación. En 1913 se construyó la gran oficina de correos en el solar oeste adyacente a la estación (obra también de los arquitectos McKim Mead & White) lo que empujaba el umbral urbano una avenida más hacia el oeste.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT | CONTEXTO HISTORICO

At the beginning of the XX century, the city of New York did not have a train connection with the rest of the country from New Jersey: the passengers had to stop at Jersey City, in the Exchange Place Station, and taking a ferry to cross the Hudson River. In 1901, the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (PRR), under the supervision of the city of New York, decided to build a tunnel to correct the lack of infrastructure: the Penn station would be the project that symbolized the entry to the city. The company decided to commission the project to the architect Charles McKim. Its architecture, monumental and influenced by the French Academicism, was appropriate to this new urban milestone.

A principios del siglo XX, la ciudad de Nueva York no tenía conexión por tren con el resto del país desde Nueva Jersey: los viajeros que querían llegar por este medio de transporte debían bajarse en Jersey City, en la estación de Exchange Place, y tomar un barco que cruzara el río Hudson. En 1901, la compañía de trenes Pennsylvania Railroad Company (PRR) bajo la supervisión de la ciudad de Nueva York decidió construir un túnel para suplir esta carencia: la nueva estación de Pensilvania sería el proyecto que simbolizaría la entrada a la ciudad. Se decidió contratar para el proyecto al arquitecto Charles McKim. Su arquitectura, deudora del academicismo francés y con un fuerte carácter monumental, parecía la idónea para este nuevo hito urbano.

The PRR plan was ambitious because it aimed to connect the Penn Station with the railroads coming from Long Island, East Manhattan, New Haven, and Connecticut. During these years, the railroad industry was transforming the city as well as its accesses. Another example was the Grand Central Station (designed by Reed and Stern through competition and McKim, Mead & White also participated), built at the same time (1910-1913).

El objetivo de la compañía de trenes PRR era ambicioso ya que pretendía a su vez conectar la estación de Pennsylvania con los trenes provenientes de la isla de Long Island, al este de Manhattan, así como de New Haven en Connecticut. Durante estos años, el ferrocarril estaba transformando la ciudad así como el acceso a la misma; este es el caso que la estación de Grand Central (proyectada por Reed and Stem, mediante un concurso que ganaron a la propia oficina de arquitectura McKim, Mead & White) se construyo prácticamente al mismo tiempo (1910-13)

ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES | CUALIDADES ARQUITECTÓNICAS

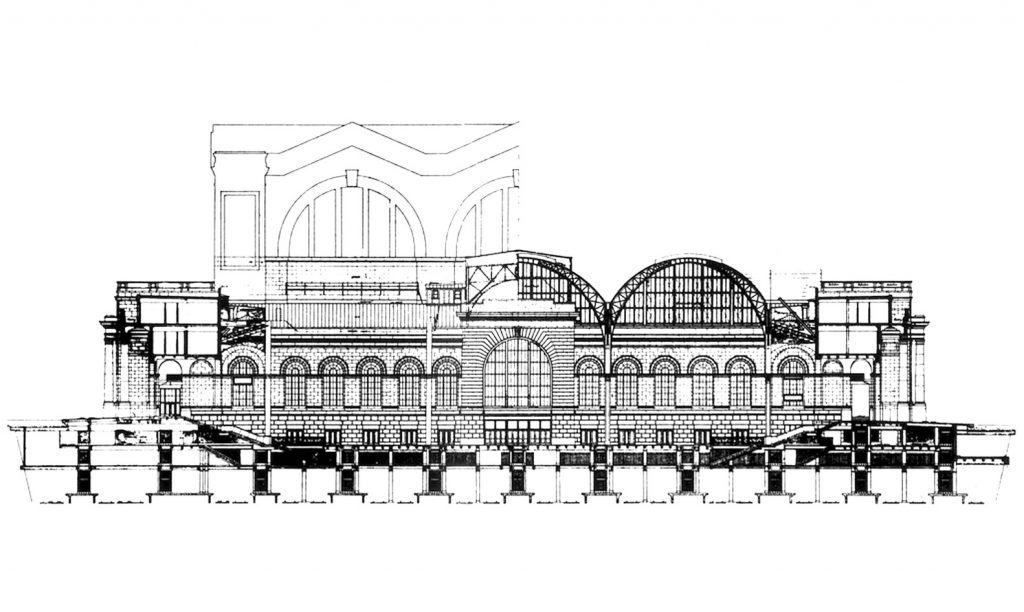

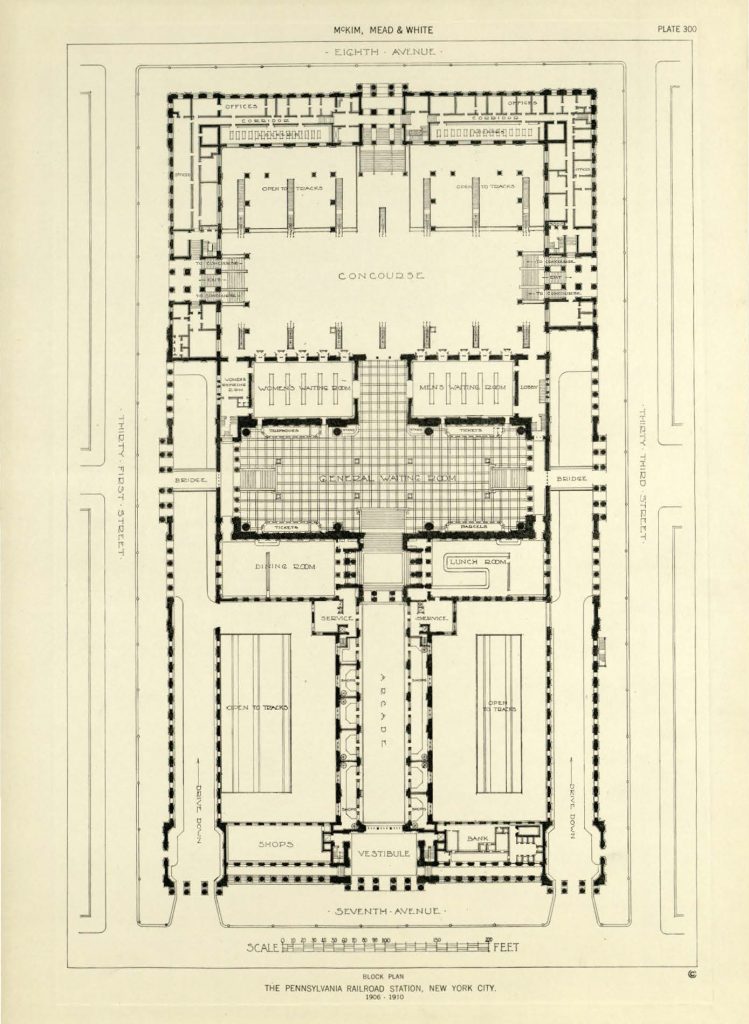

We are analyzing the McKim, Mead & White project from the movement of the passenger that arrived or departed from the city. The station was a series of scenarios that, ceremoniously, transported you from the noise of the city to the comfort and rest of the train trip. Its plan had sharp divisions made of thick walls finished in stoned that offered this diagrammatic reading. The different materiality and textures, the horizontal or vertical direction of its spaces, and the natural light control of each room reinforced this idea.

El proyecto de McKim, Mead & White se entiende estudiándolo desde la propia acción de llegar a la ciudad o partir desde ella. La estación era una concatenación de escenarios que, de forma ceremoniosa, te trasladaban desde el bullicio de la ciudad al confort y el descanso del viaje en el tren. Su planta, fuertemente compartimentada por gruesos muros revestidos de piedra ofrecen esa lectura diagramática que se veía reforzada por sus distintas materialidades, la proyección horizontal o vertical de sus espacios y el control lumínico de cada estancia.

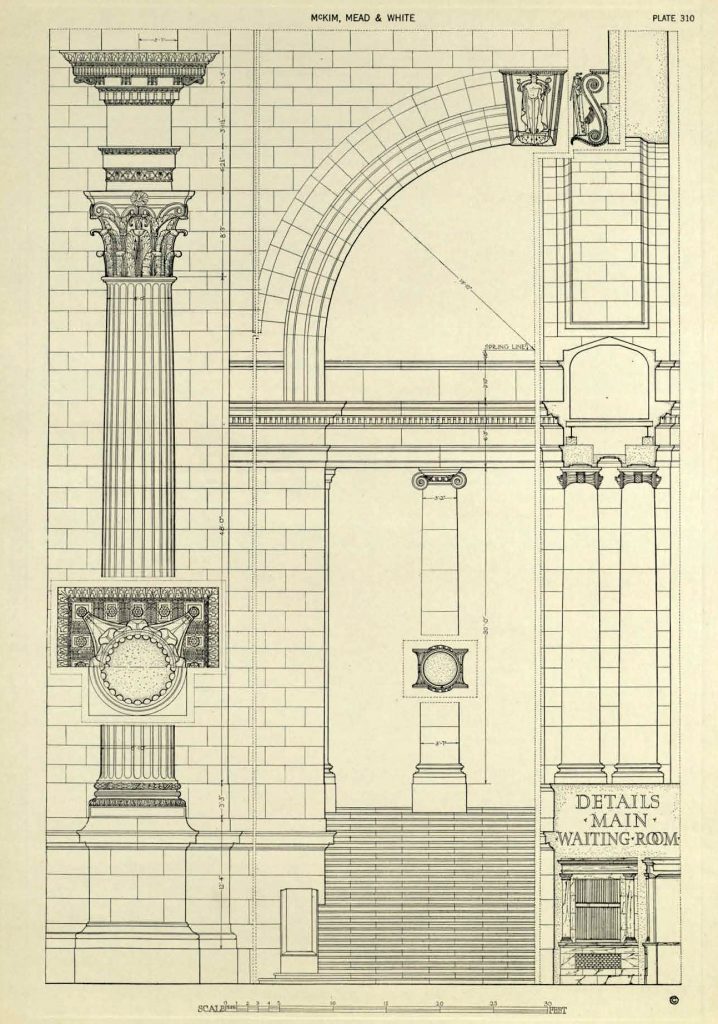

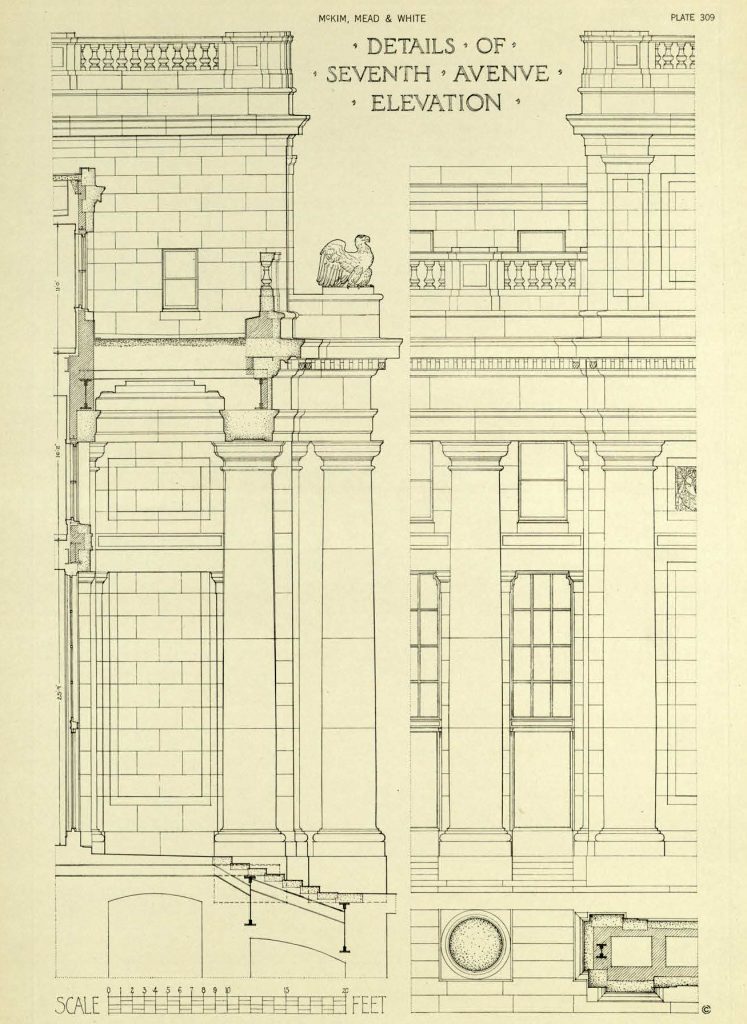

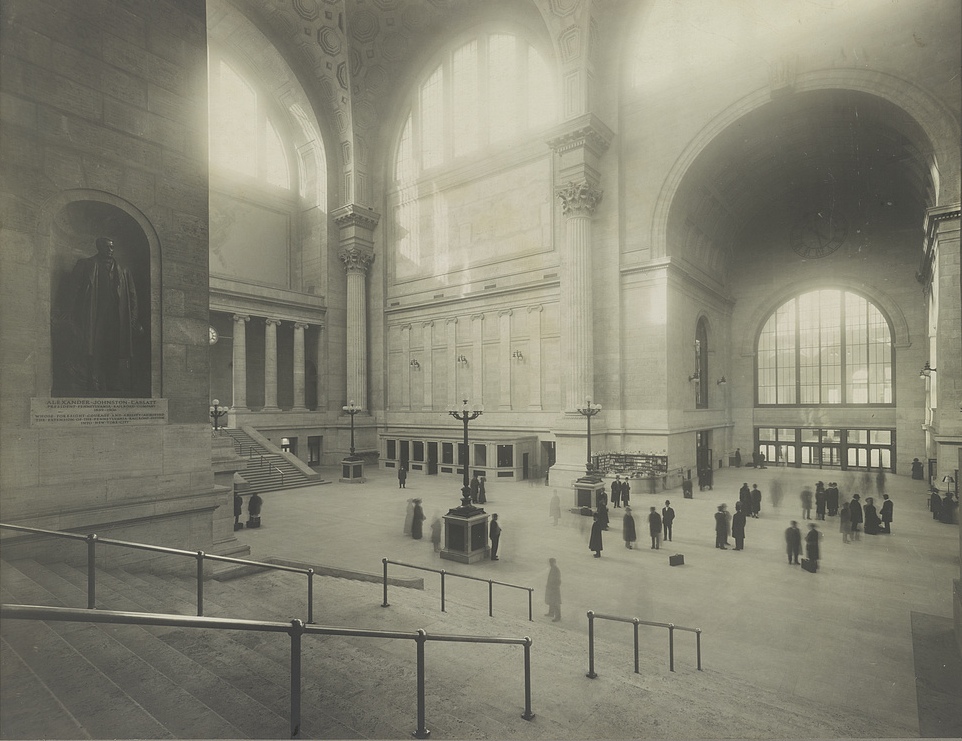

A double perimeter wall divided the interior rooms from the street and strengthening the threshold experience of introducing to a different place. Once the passenger was inside (via the seventh avenue where the main entrance was located), and after trespassing the lobby, he would walk through a commercial arcade. The sunlight entered through glass openings situated in the upper part of the arches, and it was a preface to the main waiting room. Until this moment, McKim, Mead & White mainly worked with horizontal spaces where the repetition of elements (columns and arches mainly) stretched the vanishing point of the visitor. On the other hand, the waiting room was a vertical space. The passenger could access from the street through three staircases located on each of its four sides. From the above of stairs, one could understand the space through a higher view to, then, walk down and walk into the crowd of the station. Eight thick stone columns supported a large vault covered with marble coffers. The sunlight also entered through the arches that supported the vault. Nonetheless, unlike the space of the arcade, its size and higher position allowed a brighter space. The amount of natural light created a contrast effect with the heaviness of the area and provoked a noble character in the waiting room. It was opposed to the last stage of the station: the Concourse. This vestibule had a similar height to the waiting area because it went down to the train platforms. In this space, metal was the main structural element (columns and roof). The columns, located between the different train tracks, provoked an isotropic spatial effect. The solemnity of the waiting area disappeared. The industrial aesthetic was the desired effect to access to the train, similar to the aesthetic of the railroad industry.

Un doble muro perimetral separaba las estancias interiores de la calle forzando la experiencia de umbral que te introduce en un lugar diferente. Una vez dentro (accediendo desde la séptima avenida – su entrada principal) y tras traspasar el vestíbulo, el viajero tendría que transcurrir por una arcada comercial. Ésta se iluminaba de forma natural a través de unas vidrieras en la parte superior de los arcos y ofrecería un preámbulo de la sala de espera general. Si McKim, Mead & White hasta este momento habían ido concatenando varios espacios horizontales, donde la repetición de elementos (columnas y arcos principalmente) forzaban el punto de fuga del espectador, la sala de espera era un interior totalmente vertical. Se accedía a ella, por tres de sus cuatro lados, mediante unas escaleras que, primero te permitían entender el interior desde una altura privilegiada para luego sumergirte en el bullicio de la entrada a la estación. Ocho gruesas columnas de piedra soportaban una gran bóveda recubierta por casetones de mármol. Al igual que en la arcada, el espacio se iluminaba por unos ventanales de vidrio localizados en la parte superior de los arcos que daban paso a la bóveda. Sin embargo, debido a su tamaño, y su posición más alta respecto al resto de la ciudad, la iluminación, como se puede observar en las fotografías, era mucho más intensa. La gran cantidad de luz natural contrastaba con la materialidad del espacio: Los muros y la bóveda, revestidos en distintos tipos de piedra, provocaban un efecto de pesadez en el espacio que le otorgaba un carácter solemne. Esto contrastaba con el último escenario de la estación: el vestíbulo de acceso a los trenes o Concourse. Este vestíbulo tenía una altura similar a la sala de espera ya que se hundía en una doble altura invertida que permitía acceder mediante unas escaleras metálicas al nivel sótano desde donde salían los trenes hacia New Jersey. En este caso, toda la estructura (columnas y cubierta) están construidas con una estructura metálica vista. Las columnas se localizaban entre las distintas vías del tren provocando un efecto espacial isotrópico. La solemnidad de la sala de espera desaparecía. En este caso, una materialidad industrial es la que precede el acceso al tren, asemejándose a la propia estética de la industria del ferrocarril.

DEMOLICIÓN | DEMOLITION

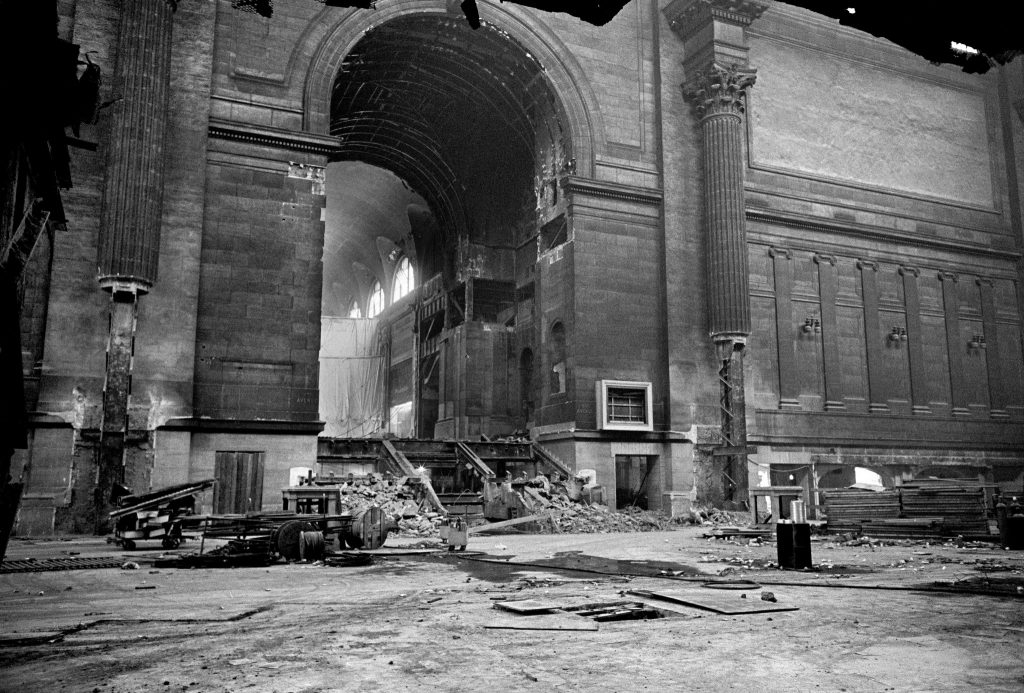

After World War II, United States fosterd the use of cars for short distances and plan to long distances. This caused a serious economical crisis in the railroad industrial that lead into its decadence and almost dissapearence. Penn Station, at that time, had very high maintenance costs that provoked large loses to the Pennsylvania Railroad company. Morevoer, its location in midtwon Mahattan, made the lot very appealing for the real estate developers. Finally, in 1962, they decided to demolish it to build the Madison Square Garden and, underneath a smaller train station. Despite the protests of several collectives, architects and the New York Times, demolition started in 1963. Nonetheless, this protests were productive since they lead to the found of New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission that, few years later, would protect Grand Central to be also demolished.

Tras el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Estados Unidos promocionó el uso del automóvil individual para distancias cortas y el avión para distancias largas, hasta el punto que la industria del ferrocarril desapareció casi por completo. Penn Station tenía unos costes de mantenimiento muy altos lo que provocaba grandes pérdidas para la compañía la compañía de trenes Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Asimismo, su localización en el centro de Manhattan, la convertían en un interesante mercancía para el mercadeo entre promotores inmobiliarios. Finalmente, en 1962 se decidió demolerla para construir el pabellón deportivo Madison Square Garden, y debajo de él, una pequeña estación de trenes totalmente subterránea. Pese a las protestas de varios colectivos, grupos de presión como el New York Times y arquitectos, la demolición de la estación comenzó en 1963. No obstante, estas protestas no fueron totalmente en vano, ya que de ellas nació la Comisión para la Preservación de Monumentos Históricos de Nueva York (New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission en inglés) que años más tarde conseguiría salvar a Grand Central de su misma suerte.

CURRENT SITUATION | ESTADO ACTUAL

Current Penn Station has been criticized because it does not allow clear wayfinding to the passenger, its low ceiling, and the lack of space during rush hours. The architectural office Skidmore, Owings & Merrill presented in 1999 a project to build a new train station in the Post Office block (also designed by McKim, Mead & White, and next to the original lot) maintaining the original façade and building on its internal courtyards. After several years of design changes and funding, the construction started in 2010. Construction is planned to be finished by the end of 2020.

La actual estación de Pennsylvania ha sido criticada por no permitir una orientación clara al pasajero, por sus bajos techos y por falta de espacio durante sus horas punta. La oficina de arquitectura Skidmore, Owings & Merrill presentó en 1999 un proyecto para construir una nueva estación de tren en el solar de la actual Oficina de correos (también proyectado por McKim, Mead & White y adyacente a la estación original ) respetando la fachada original y construyendo sobre sus patios interiores. Tras varios años de cambios del proyecto original y búsqueda de financiación, la construcción comenzó en 2010 y se espera que se termine para finales del año 2020.