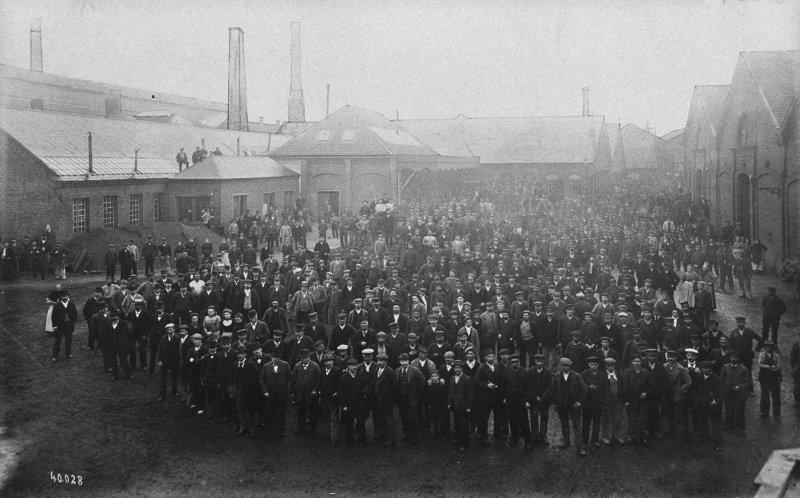

The Phalanx, was the inspiration for one of the most impressive and intelligent attempts to build Utopia – one which, on the whole, functioned for a century and which still stands today, although no longer housing an industrial community as its founder intended. This is Le Familistère in the ancient French city of Guise, the creation of the industrialist Jean-Baptiste André Godin. Born in 1817, Godin opened a small factory in 1840 producing cast-iron stoves. Soon afterwards he discovered Fourier’s ideas and became a phalansterian socialist, financing in 1853 an experimental Fourierist colony in, of all places, Texas. His own experiment was begun in 1859, next to his foundry at Guise. This was not just a well-planned philanthropic settlement for his workforce, like Saltaire near Bradford, but an experiment in social justice in which the factory workers enjoyed the benefits of the wealth produced and were involved in management and decision making.

La Phalanx, fue la inspiración para uno de los intentos más impresionantes e inteligentes de construir la utopía de Le Familistère, que funcionó durante un siglo y que aún se mantiene hoy, aunque ya no albergue una comunidad industrial como pretendía su fundador. Localizada en la antigua ciudad francesa de Guise, fue una creación del industrial Jean-Baptiste André Godin. Nacido en 1817, Godin abrió una pequeña fábrica en 1840 que producía estufas de hierro fundido. Poco después, descubrió las ideas de Fourier y se convirtió en un socialista falansteriano, financiando en 1853 una colonia Fourierista experimental en Texas. Su propio experimento se inició en 1859, junto a su fundición en Guise. Este no fue solo un acuerdo filantrópico bien planeado para la fuerza laboral, sino un experimento de justicia social en el que los trabajadores de la fábrica disfrutaban de los beneficios de la riqueza producida y participaban en la gestión y toma de decisiones.

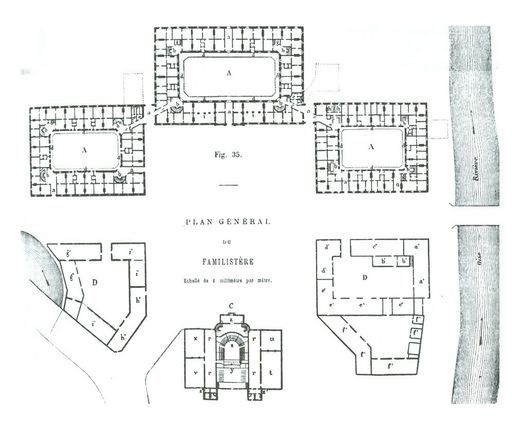

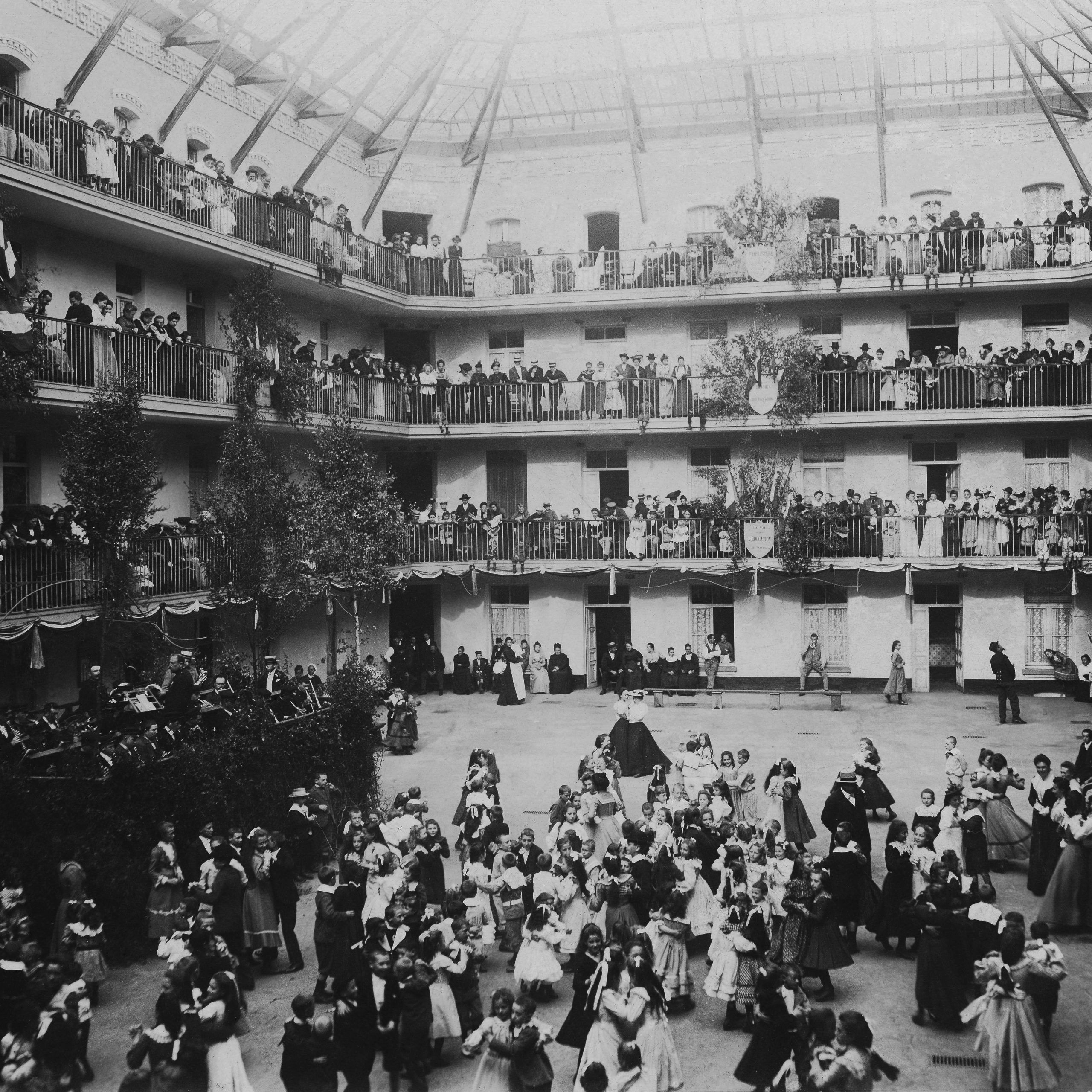

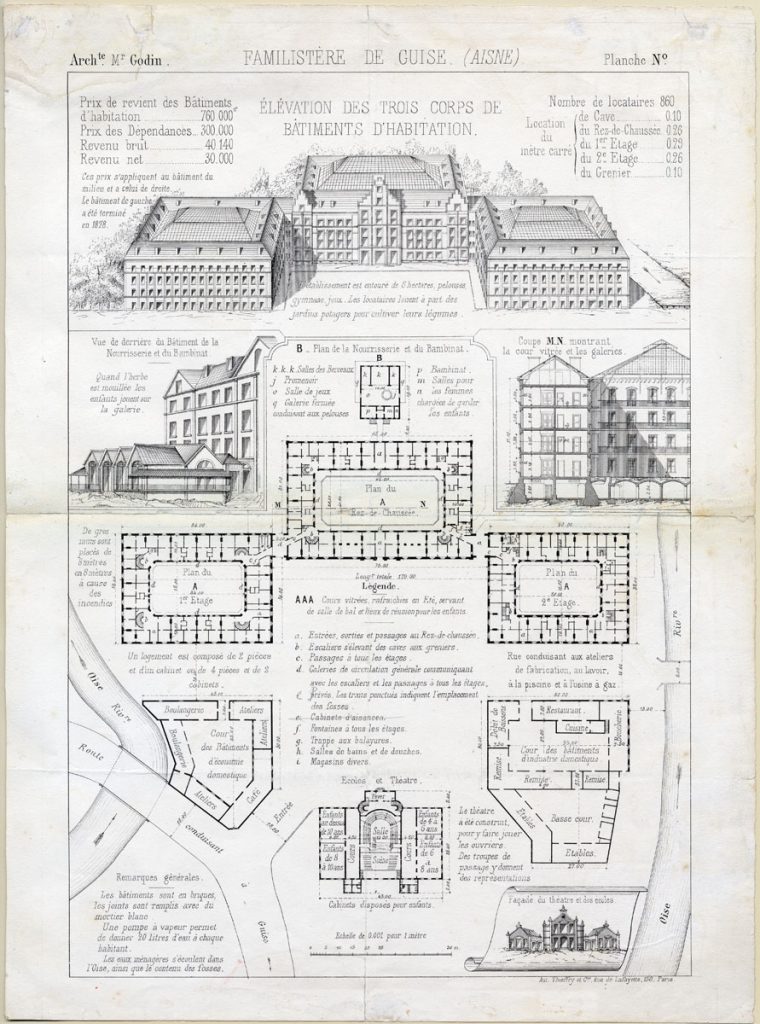

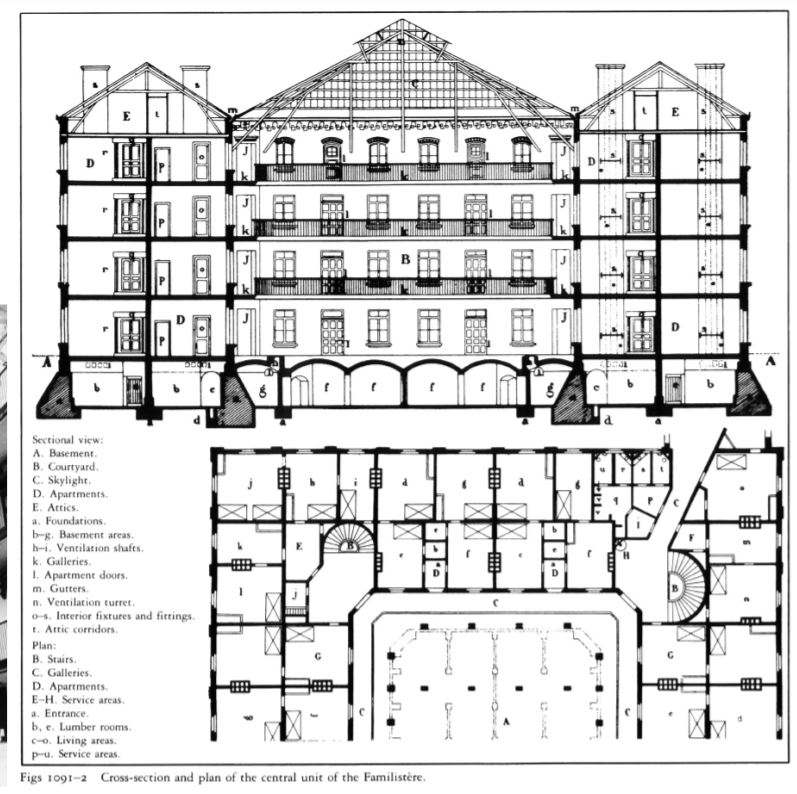

Fourier’s ideal community or Phalanx was intended to consist of precisely 1,620 people living and working in a large palatial building, vaguely modelled on Versailles but with covered street galleries, where the many facilities offered (and a controversial system of free love) could be enjoyed. Godin developed this concept. Le Familistère, or the ‘Palais social’, was designed to house some 2,000 people in about 500 apartments. These were in three connected quadrangular, glass-roofed blocks, placed close to, but quite separate from the factory. These were constructed one by one, the last being completed in 1884 and the larger central block being used for gatherings and celebrations. There was also a separate theatre, placed centrally on an axis, schools, a laundry and swimming bath, gardens and other amenities while a large basement under the main building included the essential wine cellars.

La comunidad ideal de Fourier o Phalanx consistía precisamente en 1.620 personas que vivían y trabajaban en un gran edificio palaciego, vagamente influenciado en Versalles con galerías cubiertas, donde se podía disfrutar de las numerosas instalaciones ofrecidas (y un controvertido sistema de amor libre). Godin desarrolló este concepto en Le Familistère, o “Palais social” que fue diseñado para albergar a unas 2.000 personas en unos 500 apartamentos. Estos se encontraban en tres bloques cuadrangulares conectados mediante un techo de vidrio, situados a una distancia prudencial de la fábrica. Construidos por fases, el último se terminó en 1884. El bloque central más grande se utilizaba también para reuniones y celebraciones. Además había un teatro separado, ubicado en el centro del eje, escuelas, una lavandería y un baño, jardines y otras comodidades, mientras que un gran sótano debajo del edificio principal incluía las bodegas del complejo.

Godin – who did not live in a separate house but in one of the apartments (everyone was housed according to need) – would seem to have been his own architect. The exterior of Le Familistère is typical of mid 19th-century French institutional architecture, built of patterned red brick. It is the interiors of the three communal blocks which are remarkable, with all the apartments arranged behind continuous balconies on four floors around large courts covered by overall roofs of timber and glass. There was no immediate precedent for this. The new urban railway stations as well as the Crystal Palace in London had large roofs of iron and glass but were quite different in character and function; the arcades of Paris were a more likely model, with spaces between masonry buildings covered by glazed roofs but on a much smaller scale.

Godin, que vivía en uno de los apartamentos del complejo (todos fueron alojados según las necesidades), parece que fue él mismo el arquitecto. El exterior de Le Familistère es típico de la arquitectura institucional francesa de mediados del siglo XIX y está construida con ladrillos rojos estampados. Lo más interesante del proyecto son los interiores de los tres bloques comunes donde todos los apartamentos están dispuestos detrás de balcones continuos en cuatro pisos alrededor de grandes patios cubiertos por techos de madera y vidrio. No hubo un precedente a este proeycto. Las nuevas estaciones de trenes urbanos, así como el Crystal Palace de Londres, tenían grandes techos de hierro y vidrio, pero eran bastante diferentes en carácter y función; las arcadas de París eran una referencia más cercano con espacios entre edificios de mampostería cubiertos por techos acristalados pero en una escala mucho menor.

Godin’s experiment certainly attracted attention, and it would be interesting to know whether Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson knew of it when he proposed wide glass-roofed residential streets as part of the 1868 Glasgow City Improvement Scheme, arguing that, ‘the warmth which would result from this method of building would be conducive to the health and comfort of all’. As for Godin, he wrote in 1871 that, ‘There is no point in creating cheap housing, because cheap housing is the most expensive for people; what needs to be built is housing that allows real domestic economies, a place where human well-being and happiness can be nurtured.’

El experimento de Godin atrajo la atención, y sería interesante saber si Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson lo conocía cuando propuso calles residenciales con techo de vidrio en su Plan de Mejoramiento de la Ciudad de Glasgow de 1868, argumentando que, ‘la calidez que resultaría de este método de construcción sería propicio para la salud y la comodidad de todos ‘. En cuanto a Godin, escribió en 1871 que “No tiene sentido crear viviendas baratas, porque las viviendas baratas son las más caras para las personas; lo que hay que construir es una vivienda que permita economías nacionales reales, un lugar donde se pueda fomentar el bienestar y la felicidad”.

Godin died in 1888. Eight years earlier he had set up the Co-operative Association of Capital and Labour, so that Le Familistère and the foundry passed into the shared ownership of all who lived and worked there. The experiment survived severe damage from fighting at both the beginning and end of the Great War, but failed to adapt to changed economic conditions and social tensions after the Second World War. With sad irony, the co-operative was dissolved in 1968, that very year of violent unrest when ideas of worker collectives were being proclaimed in the streets of Paris. But this was not the end. The buildings survived while the factory was sold and continues to manufacture [coast-iron] kitchenware. And in 2000 the ‘syndicat mixte du Familistère Godin’ was established to create a new cultural, tourist, social and economic utopia at Guise, a living museum and focus for cultural and educational activities. Godin’s buildings have been restored, with new apartments created in the right wing while the left wing, rebuilt after 1918, is to become an hotel.

Godin murió en 1888. Ocho años antes había creado la Asociación Cooperativa de Capital y Trabajo, de modo que Le Familistère y la fundición pasaron a ser propiedad compartida de todos los que vivían y trabajaban allí. El experimento sobrevivió al daño severo de los combates tanto al comienzo como al final de la Primera Guerra Mundial, pero no supo adaptarse a las transformaciones económicas y tensiones sociales después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Ironicamente, la cooperativa se disolvió en 1968, el mismo año que las ideas colectivistas se peleaban con disturbios violentos en las calles de París. Pero este no fue el final. Los edificios sobrevivieron mientras la fábrica se vendió y continúa fabricando utensilios de cocina. Y en el año 2000 se estableció el ‘syndicat mixte du Familistère Godin’ para crear una nueva utopía cultural, turística, social y económica en Guise, un museo viviente y centro de actividades culturales y educativas. Los edificios de Godin han sido restaurados, con nuevos apartamentos creados en el ala derecha, mientras que el ala izquierda, reconstruida después de 1918, se convertirá en un hotel.

Extract of the article ‘There is no other site like this in Europe’ from Apollo Magazine

Stamp, Gavin. (2016, September 15). ‘There is no other site like this in Europe’. Apollo.