This article is part of the Hidden Architecture Series “Tentative d’Épuisement”, where we explore the practice of an architectural criticism without rhetoric and based mainly on the physical experience of the work itself.

Este artículo forma parte de la serie “Tentativa de Agotamiento”, comisariada por Hidden Architecture, donde exploramos la práctica de una crítica arquitectónica ausente de retórica y fundamentada sobre todo en la experiencia física de la propia obra.

***

La Estrella

There is a corner in Havana that resists the weight of the passing years, that still plays a leading role in its faded memories. Estrella Rodríguez, La Estrella, walks slowly down La Rampa. If this heavy swaying through memory, without strength or clear destination, could be called walking. Up or down; down or up. Even descending towards the sea, that reflective sheet that at this time of the afternoon looks like a purple mirror, she feels as if she is crawling uphill. Her legs feel heavy. She no longer knows if it is because of the accumulated years, the steps she has always taken within the limits of this old city, or simply because she is tired of going up and down without ever managing to leave this prison: her life. As a young woman, impetuous, arrogant and brilliant, she felt how the gazes longed to capture her from the beginning to the end of the Rampa, ascending or descending the steep Calle 23, tirelessly linking the Coppelia ice cream parlour with the Malecón wall, with the sunsets burning with hope.

Hay una esquina en La Habana que resiste el peso de los años vencidos, que conserva en sus ajados recuerdos todavía un papel protagonista. Estrella Rodríguez, La Estrella, camina despacio bajando por La Rampa. Si es que a este pesado oscilar por la memoria, sin fuerzas ni destino claro, pudiera llamársele caminar. Subir o bajar; bajar o subir. Aun descendiendo en dirección al mar, esa lámina reflectante que a estas horas de la tarde le parece un espejo púrpura, tiene la sensación de arrastrarse pendiente arriba. Le pesan las piernas. Ya no sabe si es por los años acumulados, los pasos caminados siempre dentro de los límites de esta vieja ciudad o, sencillamente, porque ya se fatigó de subir y bajar sin conseguir abandonar esta prisión: su vida. De joven, impetuosa, arrogante y brillante, sentía cómo las miradas anhelaban atraparla de principio a fin de la Rampa, ascendiendo o descendiendo por la empinada calle 23, uniendo incansable la heladería Coppelia con el muro del Malecón, con los atardeceres ardientes de esperanza.

She was La Estrella, admired and passionately desired, owner of a thunderous voice that paralysed part of this city, part of this island every night; part of the Africa from which, centuries ago, her ancestors must have been torn away to be taken to Cuba as slaves. As if she wanted to unite in a single action, her singing, each of the traces left in her family tree over time, her voice rose and fell in tone, running through notes and musical scales with an astonishing ease only comparable to her vigorous walk along the Rampa. You have to climb, always climb. And stay up there, right at the top. She always knew this, and perhaps, at some point in her intense and also fleeting career, she came to believe it. In the echo of those distant years, she still seems to hear the rhythm of her heels tapping on the granite carpet that covers the pavement, catching a timid marine glow from the Caribbean on its polished surface.

Ella era La Estrella, admirada y deseada con pasión, dueña de una voz de trueno que paralizaba cada noche parte de esta ciudad, parte de esta isla; parte de la África de la que, alguno siglos atrás, sus antepasados debieron de ser arrancados para ser llevados a Cuba como esclavos. Como si quisiera unir en una sola acción, su cantar, cada uno de los posos dejados en su árbol genealógico a lo largo del tiempo, su voz subía y bajaba de tono, recorriendo notas y escalas musicales, con una facilidad asombrosa sólo comparable con su vigoroso caminar por la Rampa. Hay que subir, siempre subir. Y quedarse arriba, bien en lo alto. Siempre lo tuvo claro y, quizá, en algún momento de su intensa y también fugaz carrera, llegó a creerlo. En el eco de aquellos años lejanos le parece escuchar, todavía, el ritmo de sus tacones punzando la alfombra de granito que reviste el firme, atrapando en su pulida superficie un tímido fulgor marino procedente del Caribe.

However, the years are now piling up on her, disfiguring and burying her memories until they become small, incoherent fragments. She feels that a layer of rust, dust and ruin has settled over her life. And it is precisely ruins that she thinks about as she stops to catch her breath next to the Medical Insurance building, with the fear that has been haunting her lately on her afternoon walks along the Rampa: that one of the concrete sunshades will come loose from the façade and fall on her. Down, down, down. The ascent was nothing more than a fleeting illusion, an endless swaying that only left her with enough energy to consummate this descent. As she catches her breath, she scans with her now somewhat blurred gaze and her completely frayed memory the flat concrete roof floating above the opposite corner. In his years immune to discouragement, when he set every jazz club on fire until well into the morning, the arid presence of the concrete structure that makes up the Pabellón Cuba always seemed strange to him, out of place. In a privileged corner of La Rampa, near the Hotel Nacional and acclimatised by sweet flamboyant and acacia trees, someone decided to leave a void, to grow a tropical garden like those of his native Viñales and to shelter it with an imposing concrete structure.

Sin embargo, los años se acumulan ahora sobre ella, desfigurando y sepultando sus memorias hasta convertirlas en pequeños fragmentos incoherentes. Siente que sobre su vida se ha tendido una capa de óxido, de polvo y ruina. Y es en ruinas precisamente en lo que piensa mientras se detiene a tomar respiro junto al edificio del Seguro Médico, con el temor que últimamente le acecha en sus paseos vespertinos por la Rampa: que alguno de sus parasoles de hormigón se desprenda de la fachada y caiga sobre ella. Bajar, bajar o bajar. El ascenso no fue más que una efímera ilusión, un balanceo interminable que sólo le dejó energía para consumarse a este descenso. Mientras recobra el aliento, recorre con la mirada, ya algo borrosa, y la memoria, completamente deshilachada, la cubierta plana de hormigón que flota sobre la esquina opuesta. En sus años inmunes al desaliento, cuando incendiaba cada club de jazz hasta bien entrada la mañana, la árida presencia de la estructura de hormigón que conforma el Pabellón Cuba siempre le resultó extraña, fuera de lugar. En una esquina privilegiada de la Rampa, próxima al Hotel Nacional y aclimatada por dulces flamboyanes y acacias, alguien decidió dejar libre un vacío, hacer crecer un jardín tropical como los de su Viñales natal y procurarle cobijo con una imponente estructura de hormigón.

Without ever understanding the reasons that might have led to such an idea, he could never resist the fascination aroused by this strangeness, that the government of revolutionary Cuba had chosen this image to present itself to the world by hosting the Seventh Congress of the International Union of Architects in 1963. The group of buildings that make up this small urban unit next to the Malecón suffer from neglect and the ravages of time, barely resisting the salinity of the air, nestled in decades of oblivion and abandonment. In the ostentatious persistence of its decline, in the cracks that run down its walls, La Estrella recognises the wrinkles with which this unrepentant old age has disfigured its face, once sculpted in gleaming ebony. With her gaze fixed on the bridge leading to the Pavilion grounds, an interlude that separates that small garden from the rest of the El Vedado neighbourhood, La Estrella hums a forgotten but cheerful melody. Amidst the din of traffic descending towards the Malecón, an expert ear would distinguish, almost merging with the distant murmur of the sea, a few bars of Mala Noche. Abruptly exhaled in the afternoon by La Estrella’s hoarse throat, they seem to have been torn from some deep well.

Sin entender nunca las razones que pudieron conducir a tal idea, no pudo resistirse nunca a la fascinación que le suscitaba ese extrañamiento, que el Gobierno de la Cuba revolucionaria hubiera escogido esa imagen para presentarse al mundo albergando el Séptimo Congreso de la Unión Internacional de Arquitectos, celebrado en 1963. El conjunto de edificaciones que componen esta pequeña unidad urbana junto al Malecón sufren la dejación y el desafecto del tiempo, resisten a duras penas la salinidad del aire anidados en un olvido y abandono que dura décadas. En la ostentosa persistencia de su declive, en las grietas que descienden por sus muros, La Estrella reconoce las arrugas con las que esta impenitente vejez ha desfigurado su rostro, otrora esculpido en ébano resplandeciente. Con la mirada fija en el puente de acceso al recinto del Pabellón, un interludio que escinde aquel pequeño jardín del resto del barrio de El Vedado, La Estrella tararea una olvidada pero alegre melodía. Entre el barullo del tráfico que desciende hacia el Malecón, un oído experto distinguiría, casi fundidos con el murmullo lejano del mar, algunos compases de Mala Noche. Abruptamente exhalados a la tarde por la ronca garganta de La Estrella, parecen haber sido arrancados de algún pozo profundo.

El Jardinero Fiel

There is a corner in Havana that blooms every morning thanks to the stubborn efforts of a happy man. As a child, Joan García roamed the streets of Matanzas, engraving in his memory every cobblestone that covered the squares and streets, every plant or bush that flanked the delta on which the old colonial city sits: a triangle formed by the mouths of the San Juan and Yumurí rivers. On his often solitary walks, he saw a dream grow in him, a kind of vocation that would last until today: to be a gardener and take care of all the plants in his city. A Matanzas in terrible economic decline, as well as a slight disability caused by a complicated birth, pushed Joan to seek to fulfil the goal he had set for himself two hours north by bus. This is my 33rd year here, Joan thinks as he picks up, in the early morning light in El Vedado, the rubbish that someone insists on throwing into his garden every night. With unwavering enthusiasm and dedication, he makes up for the absolute lack of resources, support or basic equipment to be able to do his job. As he does every day, he has tidied up the access bridge to the garden, first the steps, then the ramp, which lifts visitors up, separates them from the urban traffic of La Rampa and gently lands them inside a tropical garden. To do this, he uses an old mop and a cracked metal bucket, which he brought from his home and which are certainly even older than he is.

Hay una esquina en La Habana que florece cada mañana gracias al obstinado esfuerzo de un hombre feliz. Joan García recorrió en su niñez las calles de Matanzas, grabando en su memoria cada adoquín que recubría plazas y calles, cada planta o arbusto que flanqueaban el delta sobre el que se asienta la vieja ciudad colonial: un triángulo formado por las desembocaduras de los ríos San Juan y Yumurí. En sus paseos, muchas veces solitarios, vio crecer en él una ilusión a modo de vocación que le duraría hasta estos días: ser jardinero y cuidar de todas las plantas de su ciudad. Una Matanzas en terrible decadencia económica, así como una ligera discapacidad ocasionada por un parto complicado, empujaron a Joan a buscar cumplir el objetivo que para sí mismo se había fijado a dos horas de guagua en dirección norte. Con este, son 33 ya los años que llevo aquí, piensa Joan mientras recoge, apenas aclarada la mañana en El Vedado, restos de basura que alguien se empeña en arrojar cada noche sobre su jardín. Con entusiasmo y dedicación inquebrantables, suple la absoluta ausencia de recursos, apoyo o equipamiento básico para poder ejecutar mínimamente su trabajo. Como cada día, ha adecentado el puente de acceso al jardín, pasarela de escalones primero, rampa después, que eleva al visitante, le separa del tráfico urbano de La Rampa y le hace aterrizar con delicadeza en el interior de un jardín tropical. Para ello, utiliza una vieja fregona lampiña y un cubo de chapa resquebrajado, que él mismo trajo de su casa y que con total seguridad tienen incluso más años que él.

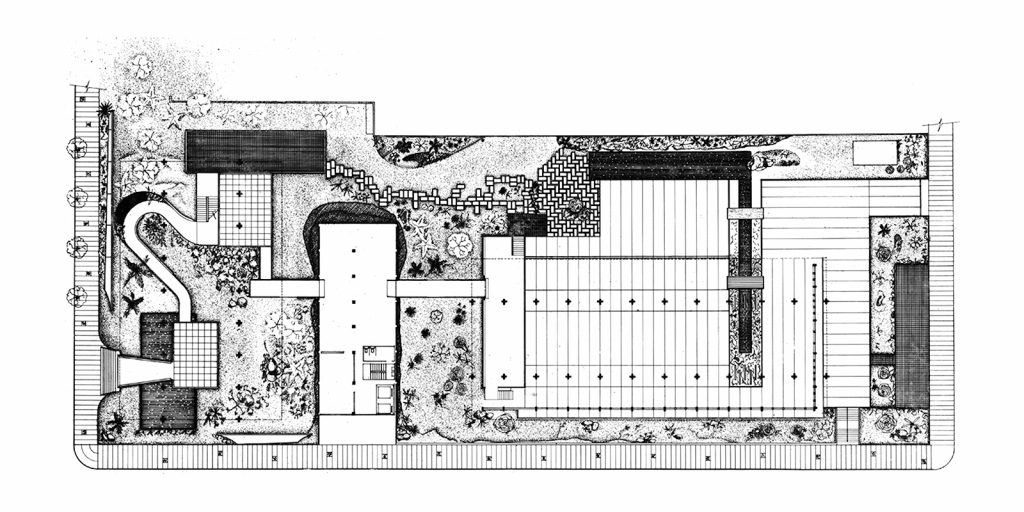

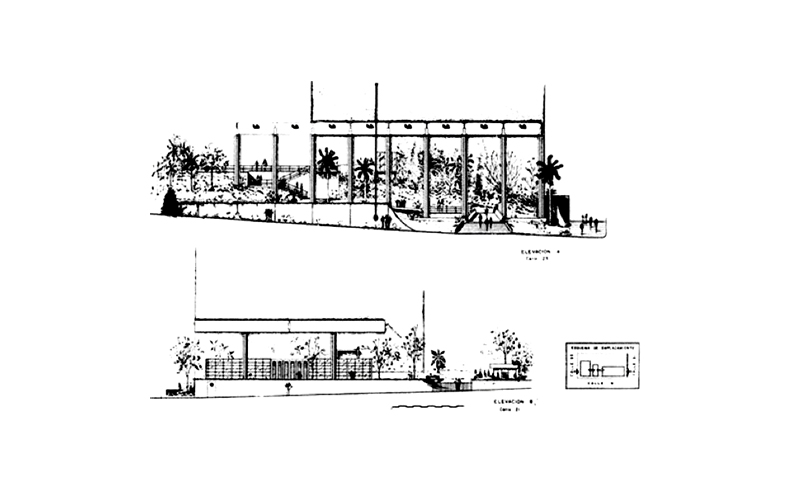

Once the boundary between the garden and the city has been crossed, via the access bridge, a grid of nine slender, two-metre-high concrete pillars supports a roof made of prefabricated beams and coffers. The proportions of each of the elements that make up this structural framework distort the perception of the whole. The volume of air collected under this modulated and articulated roof, as well as the organic layout of paths, flower beds and plantings, provide a feeling of lightness that contradicts the material nature of concrete. Joan, for his part, feels that when he enters the garden of the Pabellón Cuba, it is as if he were being devoured by an enormous animal, a kind of urban Moby Dick, stranded in a block of El Vedado and yet offering a welcoming vegetal refuge in its jaws. The projection of the concrete roof is aligned with the pillars that support it on its shorter side. However, along its longest edge, composed of nine cruciform supports, the roof juts out towards the city by a quarter of its total width, a cantilever that is also repeated towards the interior of the plot, almost in contact with the residential and office building that separates the two distinct areas of the exhibition space and garden. This overhang provides protection from the rain and sun, but unfortunately not from the wind, and encourages the growth of certain species that are thus protected from the relentless Havana sun.

Una vez franqueada la frontera entre jardín y ciudad, atravesando el puente de acceso, una malla de 9 x 2 esbeltos pilares cruciformes de hormigón soporta una cubierta de vigas y casetones prefabricados. Las proporciones de cada uno de los elementos que componen este entramado estructural distorsionan la percepción del conjunto. El volumen de aire recogido bajo esta cubierta modulada y articulada, así como el trazado orgánico de caminos, parterres y plantaciones, proporcionan una sensación de liviandad que contradice la naturaleza matérica del hormigón. Joan, por su parte, siente que al acceder al jardín del Pabellón Cuba es como si fuera devorado por un enorme animal, una suerte de Moby Dick urbano, varado en una cuadra de El Vedado y que, sin embargo, ofrece en sus fauces un acogedor refugio vegetal. La proyección de la cubierta de hormigón está alineada con los pilares que la sostienen en su lado más corto. Sin embargo, a lo largo de su arista más larga, la compuesta por nueve soporte cruciformes, la cubierta vuela hacia la ciudad un cuarto de su anchura total, voladizo que también se repite hacia el interior de la parcela, casi en contacto con el edificio de viviendas y oficinas que separa los dos ámbitos diferenciados del espacio expositivo y jardín. Este vuelo garantiza protección frente a la lluvia y el sol, desgraciadamente no contra el viento, y favorece el crecimiento de determinadas especies protegidas así del implacable sol habanero.

The garden has no water connection for irrigation, so Joan goes around each plant with a plastic watering can whose colour has been rendered imperceptible by time and the sun. Between trips, quenching the thirst of the different species that live here, Joan takes the opportunity to collect the dry leaves that have fallen on the paths. The water supply is located at the top of the garden, in the bar, so he has to walk along the winding path, which ends with a flight of stairs, every time he needs to refill the planter with water. This route winds its way up the slope of Calle 23, which, despite the distance created by the roof and vegetation, allows its presence to filter through the framework of pillars and the highest branches. Joan stops at the highest point of the path, before climbing the last flight of stairs, to take a breather and wipe the sweat from his forehead with a handkerchief that reads ‘Viva Cuba Libre’. It has taken him two hours, well into the day, going up and down, making and unmaking the same path, laden with his watering can, now empty, overflowing on the descent.

El jardín no dispone de conexión de agua para el riego, por lo que Joan recorre cada planta con una regadera de plástico de un color que el tiempo y el sol han hecho imperceptible. Entre trayecto y trayecto, aplacando la sed de las diferentes especies que aquí habitan, Joan aprovecha para ir recogiendo las hojas secas que han ido cayendo sobre los caminos. La toma de agua se encuentra en la parte superior del jardín, en el bar, por lo que debe recorrer el sinuoso camino culminado con un tramo de escaleras cada vez que necesita rellenar de agua la jardinera. Este recorrido traza unos meandros en una ascensión que sigue la pendiente de la calle 23 que, a pesar de la distancia establecida por la cubierta y la vegetación, deja filtrar su presencia a través del entramado de pilares y las ramas más altas. Joan se detiene en el punto más alto del camino, antes de ascender el último tramo por escalera, para tomar un respiro y secarse el sudor de la frente con un pañuelo que reza “Viva Cuba Libre”. Lleva dos horas, ya bien entrado el día, subiendo y bajando, haciendo y deshaciendo el mismo camino cargado con su regadera de agua; ahora vacía, rebosante en el descenso.

Having caught his breath, he takes the opportunity to clean the gleaming bust of José Martí with the same handkerchief that wiped away his sweat; an element that presides, under the Cuban flag, over the garden space of the Cuba Pavilion. ‘To create is to fight, to create is to win’. Oblivious to the sun beating down on this April afternoon, Joan enjoys the sea breeze that runs through the garden, filtering under the deck like the boisterous songs of the birds that populate the flamboyant trees of La Rampa. Something inside him seems to suddenly activate. He picks up the watering can from the ground and energetically sets off on the last journey of the day to fill it with water. A sharp smile spreads across his face, lighting up this urban oasis with joy: next, he will prune the laurels in the back garden.

Recobrado el aliento, aprovecha para limpiar con el mismo pañuelo que apagó su sudor el resplandeciente busto de José Martí; elemento que preside, bajo la bandera cubana, el espacio del jardín del Pabellón Cuba. “Crear es pelear, crear es vencer”. Ajeno al sol que desciende en picado este mediodía de abril, Joan disfruta de la corriente marina que recorre el jardín, filtrándose bajo la cubierta como los cantos alborotados de las aves que pueblan los flamboyanes de La Rampa. Algo en su interior parece activarse de repente. Recoge la regadera del suelo y emprende enérgicamente el último trayecto del día para llenarla de agua. Una afilada sonrisa se dibuja en su rostro, iluminando de alegría este oasis urbano: a continuación podará los laureles del recinto trasero.

El objetivo

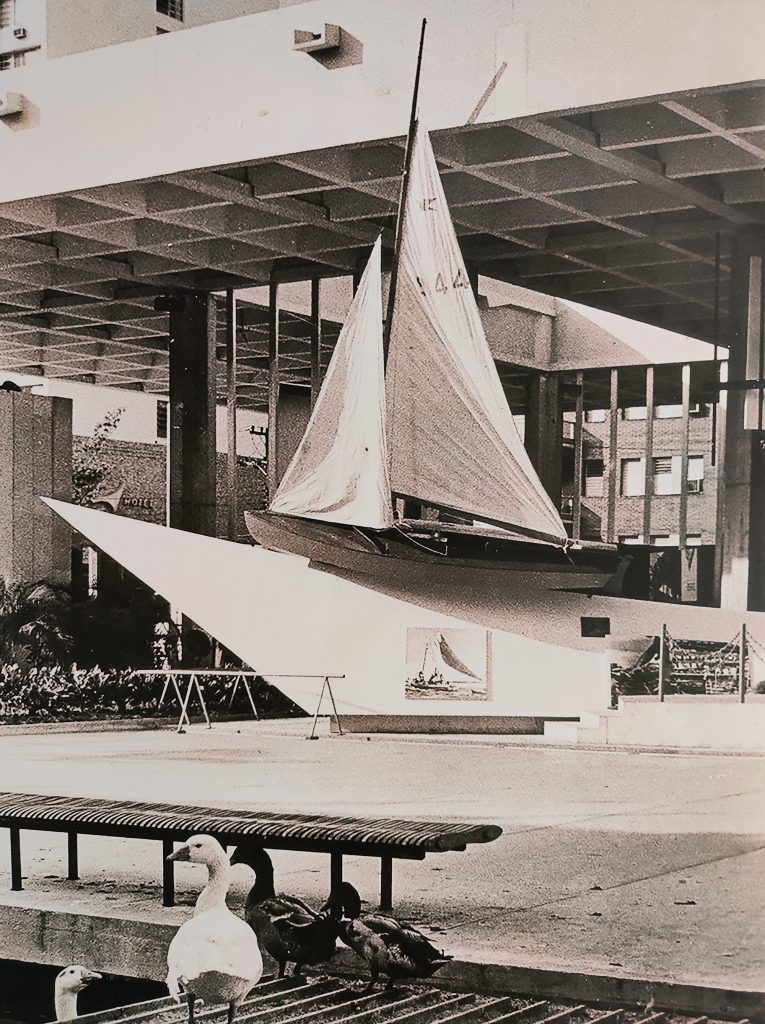

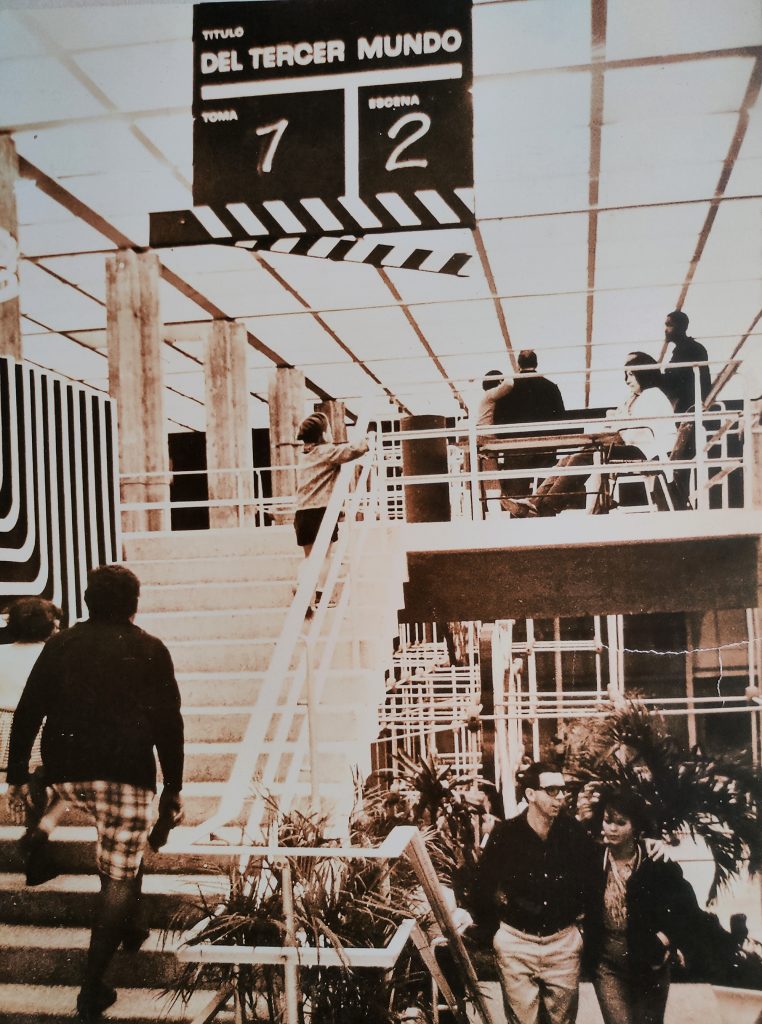

There is a corner in Havana that every afternoon paints its planes cream, amber, and pink at the top; dark blue, purple, and violet at the bottom. Ricardo Cue drives quickly along the Malecón, the headlights just turned on even though the sky is still ablaze with Caribbean autumn flames. With the convertible’s top down, he feels the salt spray from the waves crashing against the Malecón fall on his forehead in the form of an almost imperceptible drizzle. Tonight is an important night. Well equipped with his Leica camera, various lenses and a good supply of film, he arrives, somewhat late for the imminent opening, to cover a report on the Seventh Congress of the International Union of Architects. He does not have much information about it, but a contact of his at Radio Nacional has managed to get him this assignment for a French trade magazine. His task is clear: to capture the festive atmosphere that will presumably unfold under the shelter of the Pabellón Cuba, as well as the many works of art by Cuban artists that will be on display to the public – meaning the world as the public – from today, 29 September, until 3 October. He knows this area of the city well, as he frequents its corners, even the darkest ones, almost daily.

Hay una esquina en La Habana que cada tarde tiñe sus planos de color crema, ámbar, rosa en la parte superior; azul oscuro, púrpura, violeta en la inferior. Ricardo Cue circula deprisa por el Malecón, los faros recién encendidos a pesar de que el cielo todavía arde en llamas de otoño caribeño. Con la capota del convertible retirada, siente el salitre que las olas escupen contra el Malecón caer sobre su frente en forma de una garúa casi imperceptible. Hoy es una noche importante. Bien equipado con su cámara Leica, diferentes objetivos y un buen arsenal de carretes acude, con algo de retraso ya ante la inminente apertura, a cubrir un reportaje sobre el Séptimo Congreso de la Unión Internacional de Arquitectos. No dispone de demasiada información al respecto, pero un contacto suyo de la Radio Nacional ha conseguido pasarle este encargo para una revista especializada francesa. Su cometido es claro: retratar el ambiente festivo que, presumiblemente, se desarrollará al abrigo del Pabellón Cuba, así como las múltiples obras de arte de autores cubanos que se expondrán al público – queriendo decir mundo por público – desde hoy, 29 de septiembre, y hasta el próximo 3 de octubre. Esta zona de la ciudad la conoce bien, pues frecuenta sus rincones, incluso los más oscuros, casi a diario.

Walking down the Rampa to the sea, stopping at every club to have a drink and listen to some music, discuss literature or simply lose himself in his thoughts is an activity that defines his nature better than calling himself a photojournalist. The Pabellón Cuba, however, is a refreshing novelty for him, as well as for the entire city of Havana. He has seen the work being carried out hastily in recent months, but he has not yet crossed the access bridge or walked through its interior garden on different levels. Camera in hand, he makes his way through the crowd that is already filling this corner of Havana in the afternoon. He doesn’t have much time to notice the details. His radio contact told him that various political, military and social authorities would be meeting before the opening ceremony at the back of the Pavilion.

Descender la Rampa hasta el mar, deteniéndose en cada club a tomar trago y escuchar algo de música, discutir sobre literatura o sencillamente perderse en sus pensamientos es una actividad que define su naturaleza mejor que el hecho de hacerse llamar reportero gráfico. El Pabellón Cuba, sin embargo, supone una refrescante novedad para él, así como para toda la ciudad de La Habana. Ha visto las obras ejecutarse con premura en los últimos meses, pero todavía no ha franqueado el puente de acceso, no ha recorrido su jardín interior en diferentes niveles. Cámara en mano, se hace paso a través de la multitud que ya abarrota este rincón de la tarde habanera. No tiene demasiado tiempo para fijarse en detalles. Su contacto de la radio le comentó que diferentes autoridades políticas, militares y sociales se encontrarían reunidas antes del acto de inauguración en la parte trasera del Pabellón.

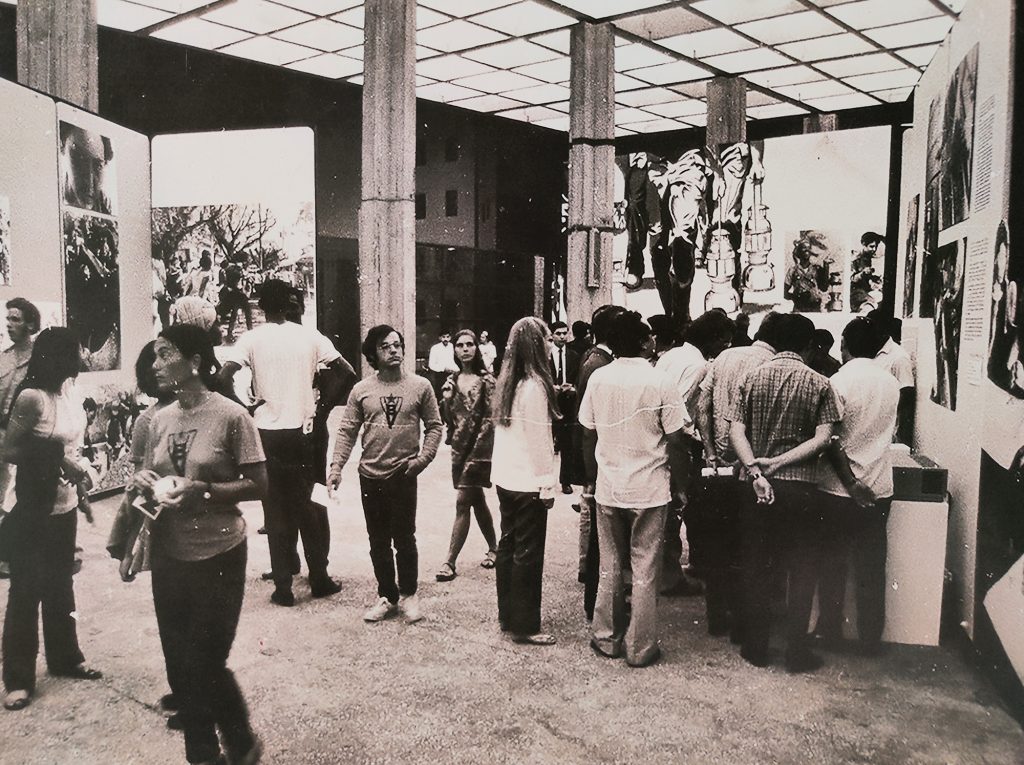

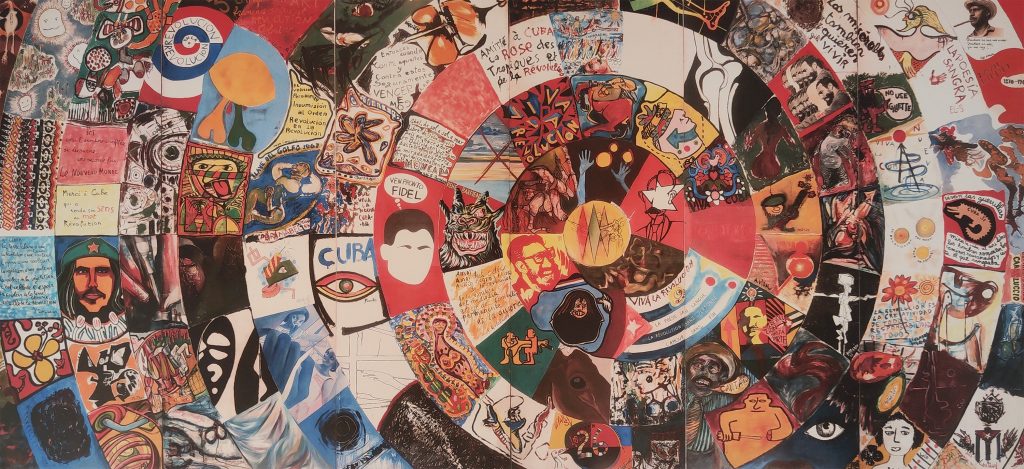

At first glance, he is struck by the immense roof that seems to float above the shapeless mass of enthusiastic young people surrounding various works of art, exhibition panels, portraits of Camilo Cienfuegos, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara himself in an atmosphere of frenzied celebration. Despite some international pressure from the so-called ‘Western world’ to prevent this congress from being held in Havana, today Cuba shows the world the success of its Revolution. Quick as a flash, Ricardo Cue weaves his way through plants, groups of students and some military personnel along the path that leads up to the rear of the Cuba Pavilion. Set on a rectangular plot measuring 1 by 3, the exhibition space and urban garden is structured into two autonomous volumes, separated by an office and residential tower that, inexplicably, divides and articulates the programme into two different spaces. In fact, the ground floor of the tower is part of the route and the exhibition space, as it is necessary to cross it via a gallery to access the interior of the venue.

A simple vista le sorprende, eso sí, la inmensa cubierta que parece flotar sobre la mancha informe compuesta de huestes de jóvenes entusiastas rodeando diferentes obras artísticas, paneles expositivos, retratos de Camilo Cienfuegos, Fidel Castro o el mismísimo Che Guevara en un ambiente de enardecida celebración. A pesar de algunas presiones internacionales del así llamado “Mundo Occidental” para evitar que este congreso se celebrara en La Habana, hoy Cuba muestra al mundo el éxito de su Revolución. Breve como una exhalación, Ricardo Cue serpentea entre plantas, grupos de estudiantes y algunos militares por el camino que asciende hacia la parte posterior del Pabellón Cuba. Asentado en una parcela rectangular de proporciones 1 a 3, el recinto expositivo, y jardín urbano, se estructura en dos volúmenes autónomos, separados por una torre de oficinas y viviendas que, inexplicablemente, divide y articula el programa en dos espacios diferentes. De hecho, la planta baja de la torre forma parte del recorrido y del espacio de exposición, ya que es necesario atravesarla por una galería para acceder al interior del recinto.

The architectural elements that define the two environments are similar: slender concrete supports hold up a coffered ceiling that transcends the layout of this structural grid to extend its projection onto the ground. However, while the entrance area, which is smaller in size and dominated by the tropical garden and the ascending path, has a more public and open character, the rear area, despite having a larger surface area, is designed to host institutional events with more restricted access. This more private character is defined by the lower ceiling height of the covered space, with the supports and roof being less monumental in scale, delimiting a more secluded space, far removed from the openness and lightness of the front facing La Rampa. Taking pictures of different architectural details, Ricardo Cue advances little by little, his press card hanging around his neck, playing a game of concealment that brings him closer to the core of the political authorities. At the precise moment, alerted by the first bars of the national anthem, he manages to photograph Commander Fidel Castro who, followed by a procession of Cuban flags, walks solemnly to deliver the opening speech next to the bust of José Martí.

Los elementos arquitectónicos que definen los dos ambientes son similares: esbeltos soportes de hormigón que sostienen una cubierta de casetones que trasciende la disposición de esta malla estructural para ampliar su proyección sobre el suelo. Sin embargo, si la parte de acceso, de dimensiones más reducidas y protagonismo del jardín tropical y el camino de ascenso, presenta un carácter más público y abierto, la parte trasera, a pesar de disponer de una superficie mayor, está pensada para albergar actos institucionales de acceso más restringido. Este carácter más privado queda definido por la menor altura libre del espacio cubierto, presentando el conjunto de soportes y cubierta una escala menos monumental, delimitando un espacio más recogido y alejado de la apertura y ligereza del frente abierto a La Rampa. Tomando imágenes de diferentes detalles arquitectónicos, Ricardo Cue avanza poco a poco, carné de prensa colgado al cuello, desplegando un juego de disimulo que le acerque al núcleo de las autoridades políticas. En el instante preciso, alertado por los primeros compases del himno nacional, consigue retratar al Comandante Fidel Castro que, seguido por una comitiva de banderas cubanas, se dirige con paso solemne a pronunciar el discurso de apertura junto al busto de José Martí.

El bar

There is a corner in Havana where the afternoons drift by rhythmically, matching their own tropical rhythms with the Reggaeton music that the speakers release into the air. There are two hours left before closing time, Ariel mutters as he collects some empty bottles from the tables. With a cloth dampened in murky water, its pungent smell of bleach, he rubs the dried rings on the blackened plastic surfaces. Today has not been a splendid day. The bar has barely made any money, but that doesn’t really worry him too much. It doesn’t matter how many beers he serves, because the youth association of the Party that runs the small premises, barely more than a beach bar, has no financial interest in it, but simply wants to offer a space for the young people of the neighbourhood to spend their afternoons here, watching ball games on television and gradually becoming involved in the social and political dynamics of the capital of Havana.

Hay una esquina en La Habana donde las tardes se diluyen cadenciosas, acompasando sus propios ritmos tropicales con la música Reggaeton que los parlantes liberan al aire. Quedan dos horas para el cierre, masculla Ariel mientras recoge algunas botellas vacías sobre las mesas. Con el trapo humedecido en agua turbia, penetrante su olor a lejía, frota los cercos resecos sobre las superficies de plástico ennegrecido. Hoy no ha sido un día espléndido. Apenas se ha hecho caja en el bar, pero eso a él realmente no le preocupa demasiado. Es indiferente el número de cervezas que sirva, pues la asociación juvenil del Partido que regenta el pequeño local, a duras penas un chiringuito, no tiene intereses económicos en él, sino sencillamente ofrecer un espacio a los jóvenes del barrio para que pasen las tardes aquí, viendo partidos de pelota en el televisor e implicándose poco a poco en las dinámicas sociales y políticas de la capital habanera.

An unbearable sound comes from the small kitchen, a kind of electric roar from the transformer that keeps the fridge somewhat cool. Power cuts are common, although fortunately for them, they are not as frequent here in El Vedado as in other areas of the city. Despite everything, the neighbourhood retains some of the class it enjoyed decades ago, even if it is faded and practically imperceptible to eyes untrained in the harsh Cuban routine. Ariel has been in charge of this bar for a few years. At first, he did it as a favour to the association, because of his commitment to the Party and, above all, so as not to harm his son, who at that time was playing in the first baseball team. After retiring as a taxi driver, a meagre pension, barely enough to feed himself for a week, forced him to keep busy longer than he would have liked. A proud Santiago native, he always wanted to return to his city, the place where he was born and which he had longed for since the first day he arrived in Havana. He prefers not to think about it too much, to keep himself busy despite the low turnout at the Pabellón Cuba, and when his thoughts become clouded, he distracts himself by rummaging through the meagre fridge, where it is becoming increasingly difficult to find bottles of national beer. Today’s selection: Czech dark beer and a craft beer from Bilbao. It’s not a question of refined snobbery; it’s simply easier and, above all, cheaper to find international beers on the black market, arriving by sea on Canadian ships, than those produced – are they still produced? – on the island.

Desde la pequeña cocina llega un sonido insoportable, una especie de bramido eléctrico procedente del transformador que mantiene la nevera algo fresca. Los cortes de luz son habituales, aunque por suerte para ellos no tan frecuentes aquí en El Vedado como en otras zonas de la ciudad. A pesar de todo, el barrio conserva algo de la categoría que hace décadas disfrutó, aunque sea marchita y prácticamente imperceptible a ojos poco entrenados en la dura rutina cubana. Ariel lleva unos años encargándose de esta barra. Al principio lo hizo como un favor a la asociación, por su compromiso con el Partido y, sobre todo, para no perjudicar a su hijo, que por aquel entonces jugaba en el primer equipo de béisbol. Después de jubilarse como taxista, una pensión raquítica, que apenas le alcanza para la comida de una semana, le forzó a mantenerse ocupado más tiempo del que a él le gustaría. Orgulloso santiaguero, siempre quiso regresar a su ciudad, al lugar en que nació y que tanto añoró desde el primer día en que arribó a La Habana. Prefiere no pensarlo demasiado, mantenerse ocupado a pesar de la escasa afluencia de público que se acerca al Pabellón Cuba y, cuando los pensamientos se le nublan, distraerse ojeando la raquítica nevera, donde cada día es más difícil encontrar botellines de cerveza nacional. La oferta de hoy: cerveza tostada checa y una artesanal de Bilbao. No es una cuestión de refinado esnobismo; sencillamente es más sencillo y, sobre todo, barato, encontrar cervezas internacionales de estraperlo, llegadas por mar en buques canadienses, que aquellas que se producen – ¿se producirán todavía? – en la isla.

He wanders among the tables on the terrace looking for new customers, even though he knows full well that no one has arrived for hours, and this movement serves as an excuse to look out over the garden below. Located on the platform at the end of the flight of stairs, the small bar is a viewpoint overlooking the entrance and tropical garden of the Pabellón Cuba. Leaning on the railing, he observes the concrete beams that support the pavilion’s roof, positioned exactly in his favourite corner: the cantilever that extends towards La Rampa at the end of the climb. Supported by four concrete beams in an illogical overhang, this suspended balcony defines the route to follow from the garden entrance and anticipates the existence of a programme that extends beyond the view. In a way, Ariel’s corner, visible to all, is the fundamental element that activates the entire route that links the two exhibition spaces of the Pabellón Cuba. Distracted as he was, the drawn-out squeak of the metal shutter of the bookshop, located in the premises next to the bar, startles him anxiously and brings him back from his lethargy. Closing time has arrived. As he begins to clear the tables on the terrace, a group of four young people argue heatedly, paying little attention to the ball game being broadcast on the television. Ariel sweeps the floor, finishes off a sip of rum that someone left at the bottom of a glass and switches off the transformer first, then the television and the music, waiting for a well-deserved silence. Until now muffled by the music and the match, the content of the young people’s discussion is finally revealed.

Da una vuelta entre las mesas de la terraza buscando clientes nuevos, aunque bien sabe que nadie ha llegado desde hace horas, y este movimiento le sirve como excusa para asomarse al jardín de abajo. Ubicado en la plataforma que se encuentra al final del tramo de escaleras, el pequeño bar es un mirador sobre la entrada y jardín tropical del Pabellón Cuba. Recostado sobre la barandilla, observa las vigas de hormigón que soportan la cubierta del pabellón, colocado exactamente en su rincón favorito: el voladizo que se extiende hacia La Rampa al final de la subida. Sostenido por cuatro vigas de hormigón en un vuelo ilógico, este balcón suspendido define desde el acceso al jardín el recorrido a seguir y anticipa la existencia de un programa que se extiende más allá de la vista. De alguna forma, el rincón de Ariel, a la vista de todos, es el elemento fundamental que activa el recorrido completo que articula los dos espacios expositivos del Pabellón Cuba. Distraído como estaba, el chirrido arrastrado de la persiana metálica de la librería, situada en el local contiguo al bar, le sobresalta angustiosamente y le devuelve de su letargo. Llegó la hora de cierre. Mientras comienza a recoger las mesas de la terraza, un grupo de cuatro jóvenes discute acaloradamente sin prestar demasiada atención al partido de pelota retransmitido en el televisor. Ariel barre el suelo, apura un sorbo de ron que alguien dejó al fondo de un vaso y desconecta el transformador primero, el televisor y la música después, a la espera de un merecido silencio. Hasta ahora amortiguada por la música y el partido, se revela al fin el contenido de la discusión que los jóvenes todavía mantienen.

– But do you really think Madrid has already signed Mbappé?

– ¿Pero tú crees, de verdad, que el Madrid tiene ya fichado a Mbappé?