The city of Tashkent, with its almost three million inhabitants, is the capital and economic centre of Uzbekistan. Heir to the historical significance of being a key stop on the ancient Silk Road, a vital link in trade between Europe and China for centuries, it reached its zenith of splendour during Soviet rule in the mid-20th century. Its position compared to other ancient Persian cities such as Samarkand or Bukhara was always secondary, which is why it never enjoyed the cultural and material wealth that made those cities legendary. In 1966, a major earthquake reduced most of Tashkent’s urban fabric to rubble, forever veiling its most important architectural heritage in the echoes of the past. This natural disaster was, however, the main driving force behind its rebirth as one of the main industrial, economic and population centres in the former Soviet Republics. In fact, its relevance in demographic terms was remarkable, becoming the fourth most populated city, only surpassed by Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev.

La ciudad de Tashkent es, con sus casi tres millones de habitantes, la capital y centro económico de Uzbekistán. Heredera de la relevancia histórica que le otorgó el hecho de ser una de las paradas fundamentales en la antigua Ruta de la Seda, conexión fundamental para el comercio entre Europa y China durante siglos, alcanzó su cenit de esplendor durante el dominio soviético a mediados del siglo XX. Su posición frente a otras antiguas ciudades persas como Samarcanda o Bukhara siempre fue secundaria, razón por la cual nunca disfrutó de la riqueza cultural y material que hizo legendarias a aquellas. En 1966, un terremoto de gran magnitud redujo a escombros la mayor parte del tejido urbano de Tashkent, velando para siempre en los ecos del pasado su herencia arquitectónica más relevante. Esta desgracia de causa natural fue, sin embargo, el motor fundamental para su renacimiento convertida en uno de los principales centros industriales, económicos y poblacionales en el conjunto de las antiguas Repúblicas Soviéticas. De hecho, su relevancia en términos demográficos fue notable, llegando a ser la cuarta ciudad más poblada, tan solo superada por Moscú, Leningrado y Kiev.

The tabula rasa that the earthquake’s destruction caused was used by political leaders to plan and map out the ideal Soviet city, all without having to confront or negotiate with the always uncomfortable vestiges of an alien and strange past. Where previously there was a dense urban fabric of small mud and wooden buildings, narrow and unhealthy alleys with no clear hierarchy and, above all, an active cosmopolitan life, a road network of large avenues was soon built, radially converging in the administrative centre of the new Soviet Tashkent. With a very low building density, this urban core was conceived as a gigantic green void dotted with monumental government buildings and public facilities intended to represent the symbolic position of the people in the imagination of the ruling classes of the USSR. Inside this gigantic hygienist park, circulation is mainly pedestrian. The complete absence, however, of urban life outside the working hours of the state officials emphasises its empty character far above its value as the nerve centre of a large city. Outside this public hub, the layout of large blocks, surrounded by a road whose width is more typical of first-class motorways, constitutes an inhospitable and highly aggressive urban space for pedestrians. It is paradoxical to observe how, despite the effort to build a large public space for the city’s inhabitants, the centre of the new Tashkent is completely devoid of urban life, denied by a layout obsessed with traffic efficiency and the exaltation of the state.

La tabula rasa que la destrucción del terremoto causó fue aprovechada por los dirigentes políticos para planificar y trazar la ciudad ideal soviética, todo ello sin tener que enfrentarse ni negociar con los siempre incómodos vestigios de un pasado ajeno y extraño. Donde anteriormente existía un denso tejido urbano compuesto de pequeñas edificaciones de barro y madera, estrechas e insalubres callejuelas sin una jerarquía clara y, sobre todo, una activa vida cosmopolita, pronto se construyó una red viaria de grandes avenidas que confluían radialmente en el centro administrativo del nuevo Tashkent soviético. Con una densidad edificatoria muy baja, este núcleo urbano fue concebido como un gigantesco vacío verde salpicado de monumentales edificios gubernamentales y equipamientos públicos destinados a representar la posición simbólica del pueblo en el imaginario de las clases dirigentes de la URSS. En el interior de este gigantesco parque higienista, las circulaciones son fundamentalmente peatonales. La absoluta ausencia, sin embargo, de vida urbana fuera de los horarios de trabajo de los funcionarios estatales enfatiza el carácter de vacío muy por encima de su valor como centro neurálgico de una gran ciudad. Fuera de este cogollo público, el trazado de grandes manzanas, rodeadas de un viario cuya anchura es más propia de autopistas de primer orden, constituye un espacio urbano inhóspito y altamente agresivo para el viandante. Resulta paradójico observar cómo, a pesar del esfuerzo por construir un gran espacio público para los habitantes de la ciudad, el centro de la nueva Tashkent carece por completo de vida urbana, negada ésta por un trazado obsesionado por la eficiencia circulatoria y el enaltecimiento del Estado.

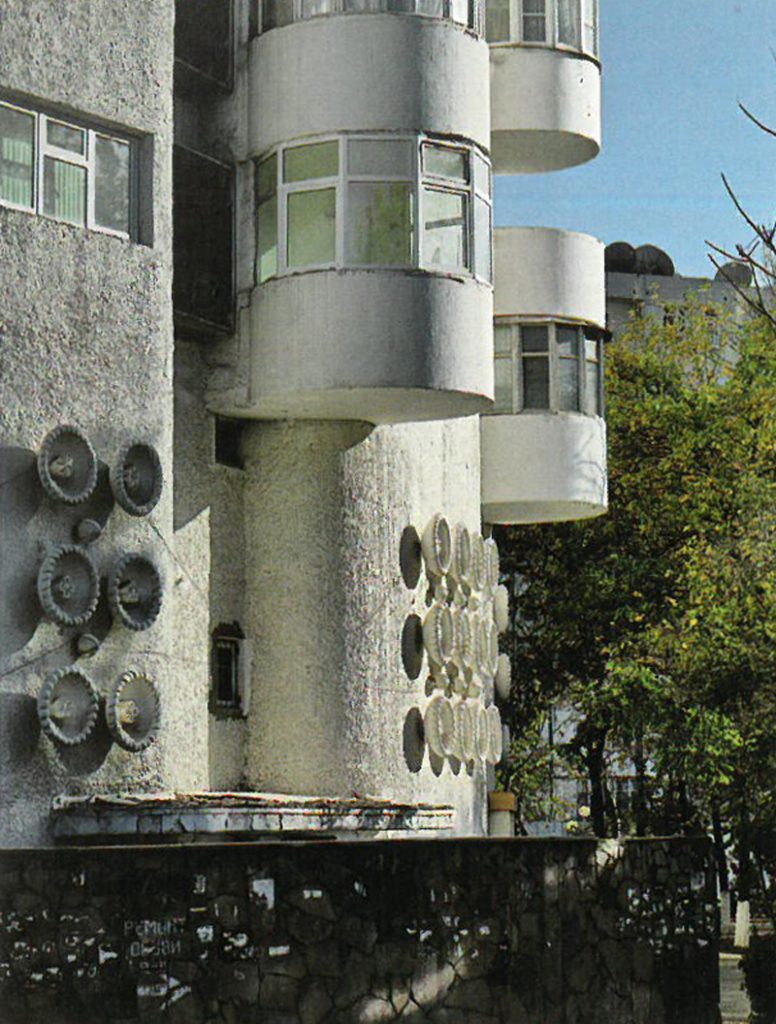

The need to rebuild a housing fabric capable of quickly accommodating all the inhabitants whose homes were destroyed by the earthquake was also used to develop innovative precast concrete construction techniques. Thus, the urban superblocks gradually accommodated blocks and towers of collective housing which, over the years and with the evolution of construction, progressively gained height until they reached twenty storeys in very short construction periods. Most of these residential constructions were characterised, as has already been stated, by a very lax urban character, but they nevertheless developed façade compositions with a high degree of ornamentation. This peculiar approach to the Persian architectural heritage, observed from the perspective of abstraction and modernity, contributes significantly to the construction of an interesting urban identity that mitigates, unfortunately only in part, the hegemonic presence of the automobile.

La necesidad de reconstruir un tejido de vivienda que fuera capaz de alojar con celeridad a todos los habitantes cuyos hogares fueron destruidos por el terremoto, fue también aprovechado para el desarrollo de innovadoras técnicas de construcción en hormigón prefabricado. Así, las supermanzanas urbanas fueron acogiendo bloques y torres de vivienda colectiva que, con el paso de los años y la evolución constructiva, ganaron progresivamente altura hasta alcanzar las veinte plantas en plazos de obra muy cortos. Caracterizadas en su mayoría, como ya se ha enunciado, por un carácter urbano muy laxo, estas construcciones residenciales desarrollaron sin embargo unas composiciones en fachada con un alto grado de ornamentación. Esta peculiar aproximación a la herencia arquitectónica persa, observada desde la abstracción y la modernidad, contribuye notablemente a construir una interesante identidad urbana que mitiga, desgraciadamente solo en parte, la presencia hegemónica del automóvil.

Among the multitude of projects executed in just a couple of decades, the flat tower popularly known as Zhemchug, which means pearl in Russian, stands out for its outstanding typological quality. The work of the architect Odetta Aidinova, it develops an interesting architectural proposal, working with the concept of type, with respect to two fundamental issues: the lack of public space in its surroundings and, secondly, the dialogue with the heritage of Persian vernacular domesticity.

Entre la multitud de proyectos ejecutados en apenas un par de décadas, destaca por su sobresaliente calidad tipológica la torre de apartamentos conocida popularmente como Zhemchug, cuyo significado en ruso es perla. Obra de la arquitecta Odetta Aidinova, desarrolla una interesante propuesta arquitectónica, desde el trabajo con el concepto de tipo, respecto a dos temas fundamentales: la nula calidad de espacio público en su entorno y, en segundo término, el diálogo con la herencia de domesticidad vernácula persa.

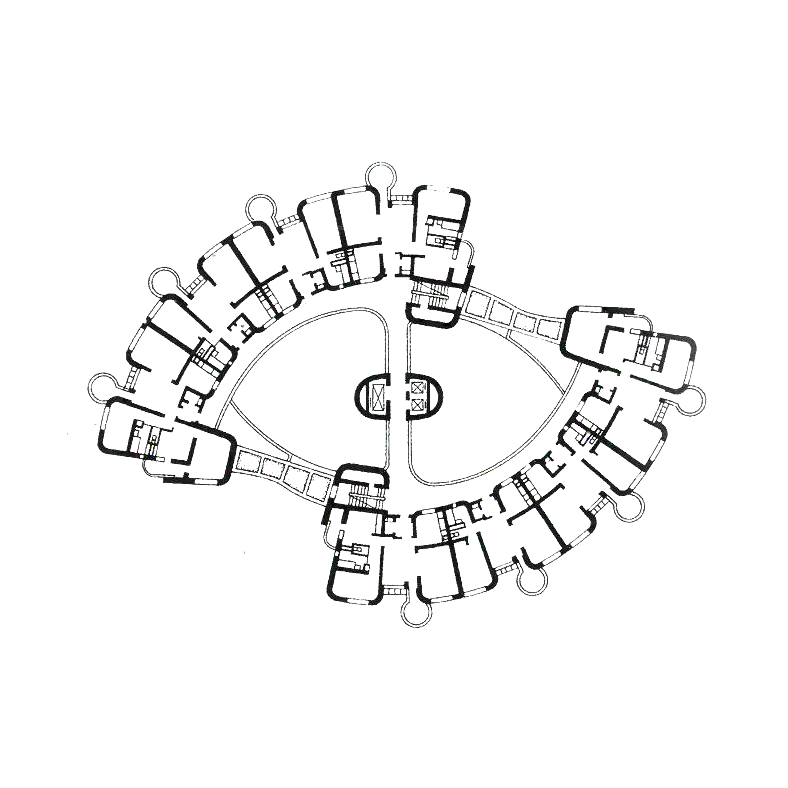

Built in concrete with sensual organic geometries, the tower is 16 storeys high, next to a busy avenue bordering the administrative centre of the city. If we look at the floor plan, the distribution of the dwellings is in two facing segments with a curved guideline, connected to each other by means of the lift core located in an intermediate position. Each of the sectors contains four pass-through flats and an emergency staircase, accessed via an open-air distribution gallery, which in turn is an extension of the walkways from the communication core. These housing units are made up of three strips and respond efficiently to Tashkent’s arid and extreme climate: hot in summer, cold in winter. From the outer gallery, access is gained through the middle bay, where a sizable anteroom transcends its function as a foyer to become a “summer room”, a climate control device that allows for a cool, sunless room during the hottest hours of the day. Directly linked to the living room and the exterior balcony on the façade, it ensures the control of draughts. The two bays at either end of the building house the rooms facing outwards and the wet rooms facing the interior gallery. The division between the different rooms of the dwellings avoids the watertight compartmentalisation of wall and door, deploying a spatial fluidity by means of large openings in the walls that link each of the rooms into a domestic whole.

Ejecutada en hormigón con sensuales geometrías orgánicas, la torre alcanza las 16 plantas de altura junto a una transitada avenida limítrofe con el centro administrativo de la ciudad. Si observamos la planta, la distribución de las viviendas se realiza en dos segmentos enfrentados de directriz curva, conectados entre sí mediante el núcleo de ascensores situado en una posición intermedia. Cada uno de los sectores acoge cuatro apartamentos pasantes y una escalera de emergencia, a los que se accede mediante una galería de distribución al aire libre, prolongación a su vez de las pasarelas procedentes del núcleo de comunicación. Estas unidades de vivienda se componen de tres bandas y responden con eficiencia al árido y extremo clima de Tashkent: caluroso en verano, frío en invierno. Desde la galería exterior, se accede a través de la crujía intermedia, donde una antesala de dimensiones considerables trasciende su función de recibidor para convertirse en una “sala de verano”, dispositivo de control climático que permite la estancia en un cuarto fresco y sin soleamiento durante las horas más calurosas del día. Vinculada directamente con el salón y el balcón exterior de la fachada, garantiza el control de las corrientes de aire. Las dos crujías de los extremos acogen habitaciones hacia el exterior y los cuartos húmedos hacia la galería interior. La división entre las diferentes habitaciones de las viviendas huye de la compartimentación estanca de muro y puerta, desplegando una fluidez espacial mediante grandes aperturas en las paredes que vinculan cada una de las estancias en un todo doméstico.

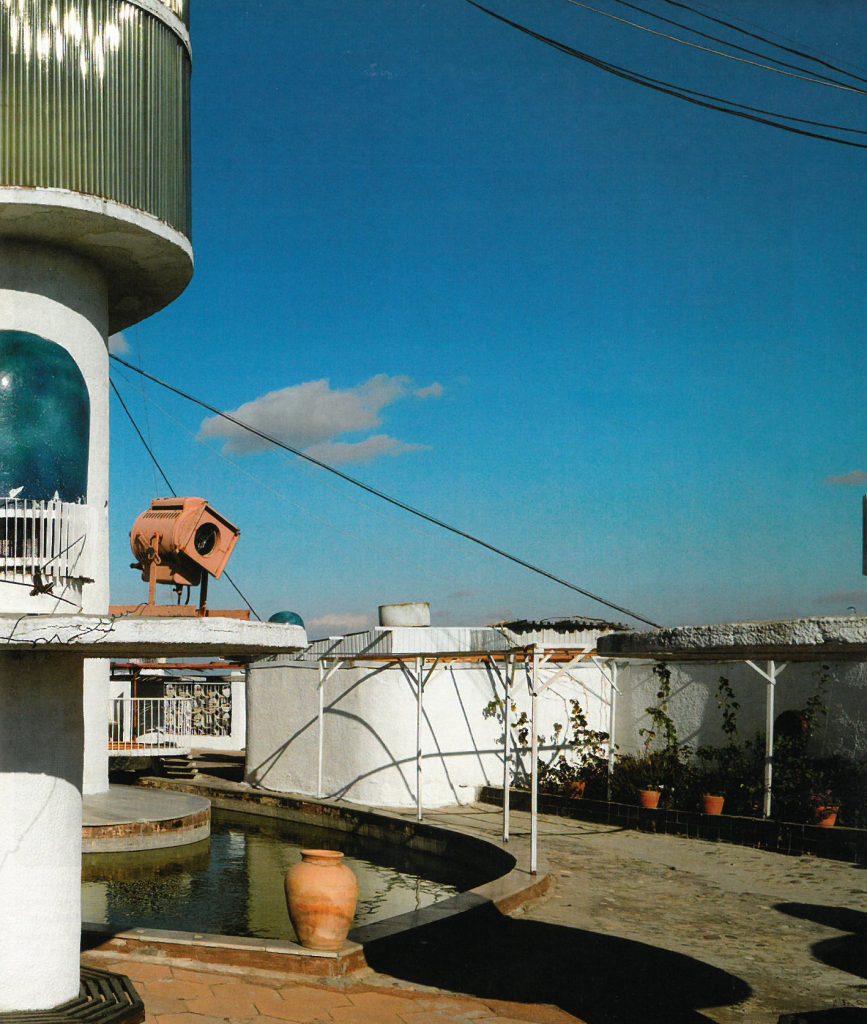

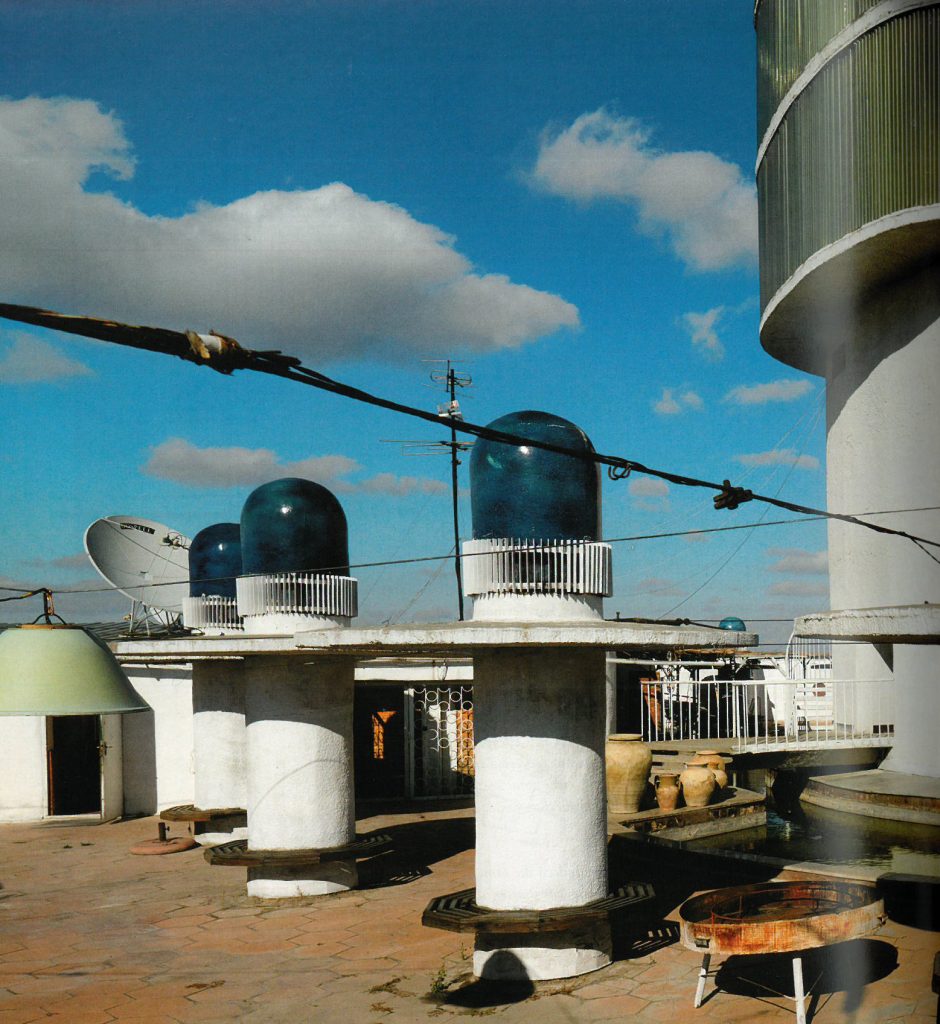

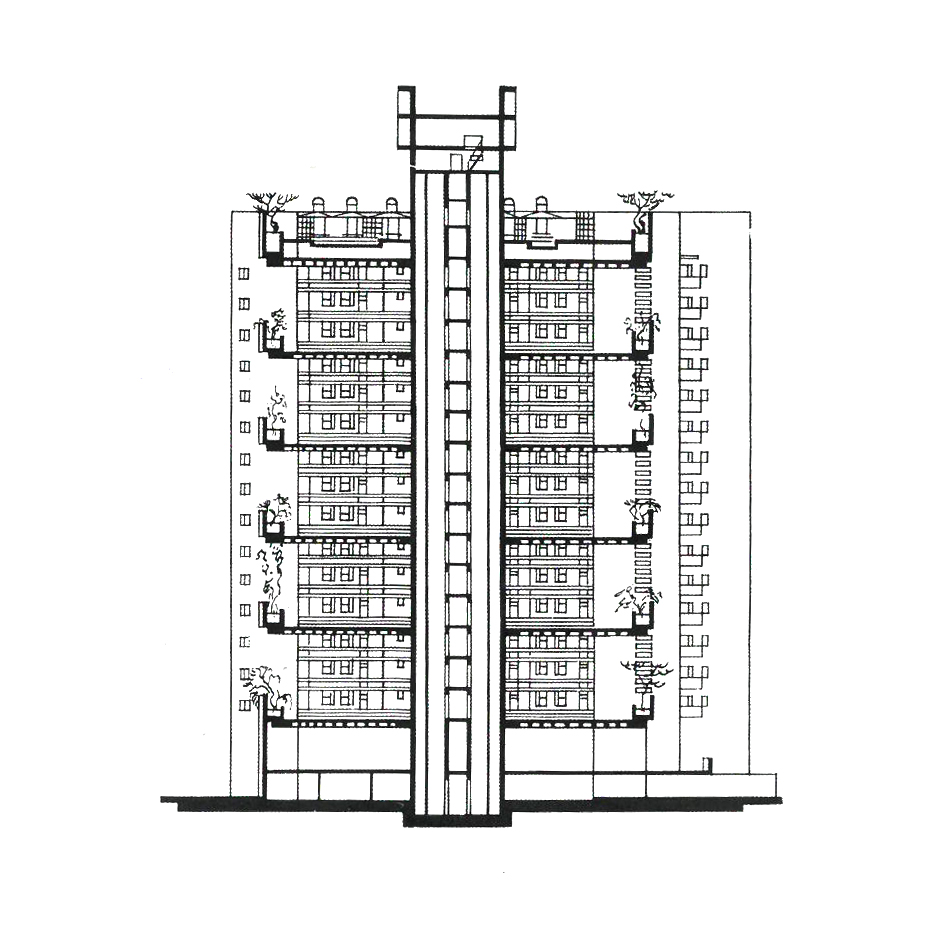

However, it is by looking at Zhemchug’s project in section that we fully appreciate the value of his innovative and daring proposal. Leaving aside the penthouse floor, the remaining 15 floors of dwellings are grouped in section into five environmental units. Thus, the three floors that make up each cluster are arranged around a communal plaza located at the level of the lower floor that makes up each group. In response to an inhospitable urban space, the architect Odetta Aidinova designed these suspended gardens to accommodate the social interaction of the inhabitants of the 24 dwellings that make up each module. These raised courtyards are delimited by the access galleries to the rear of the dwellings, while they open onto the city, guaranteeing the entry of natural light and ventilation into each of the spaces that make up the complex. They thus serve as climate control devices and social centres on a community scale.

Ahora bien, será observando el proyecto de Zhemchug en sección cuando apreciemos completamente el valor de su innovadora y arriesgada propuesta. Dejando de lado la planta de ático, las 15 plantas de viviendas restantes se agrupan en sección en cinco unidades ambientales. Así, las tres plantas que integran cada cluster se ordenan alrededor de una plaza comunitaria situada a nivel de la planta inferior que compone cada grupo. En respuesta a un espacio urbano inhóspito, la arquitecta Odetta Aidinova dispone de estos jardines suspendidos destinados a acoger la interacción social de los habitantes de las 24 viviendas que integran cada módulo. Estos patios en altura quedan delimitados por las galerías de acceso a las viviendas en su parte trasera, mientras que se abren hacia la ciudad garantizando la entrada de luz natural y ventilación al interior de cada uno de los espacios que componen el conjunto. Sirven así como dispositivos de control climático y centro social a escala comunitaria.

It is essential to understand these suspended gardens and the dwellings surrounding them as a neighbourhood unit, especially in relation to the Persian urban tradition. In this way, they constitute architect Odetta Aidinova’s particular interpretation of the Uzbek Mahalla, which in the traditional city corresponds to a grouping of dwellings around a semi-private communal courtyard, closely linked to the street from which it is accessed, building a high-density urban fabric.

Es fundamental entender estos jardines suspendidos y las viviendas que los rodean como una unidad vecinal, sobre todo en relación a la tradición urbana persa. De esta forma, constituyen la particular interpretación de la arquitecta Odetta Aidinova de los Mahalla uzbekos, que se corresponden en la ciudad tradicional con una agrupación de viviendas en torno a un patio comunitario semiprivado, vinculado estrechamente con la calle desde la que se accede, construyendo un tejido de alta densidad urbana.

Far from the fascination that Zhemchug’s project may provoke from a typological point of view, assuming a more than questionable definition of architecture as an autonomous discipline, it is necessary to warn of the risks that this strategy entails for the necessary purpose of building the city. It is true that the physical context did not allow for the development of a community life linked to the daily activity of Tashkent, which was otherwise non-existent in this area. However, this introverted approach to the urban question, bringing together all the possible spaces for social relations inside the buildings, should be limited to exceptional projects such as this one, and should not be the norm for future developments that aim to improve the environmental conditions of the fabric in which they are located.

Lejos de la fascinación que nos pueda provocar el proyecto de Zhemchug desde un punto de vista tipológico, asumiendo para ello una más que cuestionable definición de la arquitectura como una disciplina autónoma, es necesario advertir de los riesgos que conlleva esta estrategia para el fin necesario de construir ciudad. Es cierto que el contexto físico no permitía el desarrollo de una vida comunitaria vinculada con la actividad cotidiana de Tashkent, inexistente por otro lado en esta zona. Sin embargo, esta aproximación introvertida a la cuestión de lo urbano, aglutinando en el interior de los edificios todos los posibles espacios de relación social, debería limitarse tan solo a proyectos puntualmente excepcionales como este y no constituir la norma de cara a futuros desarrollos que ambicionen mejorar las condiciones ambientales del tejido en que se asienten.