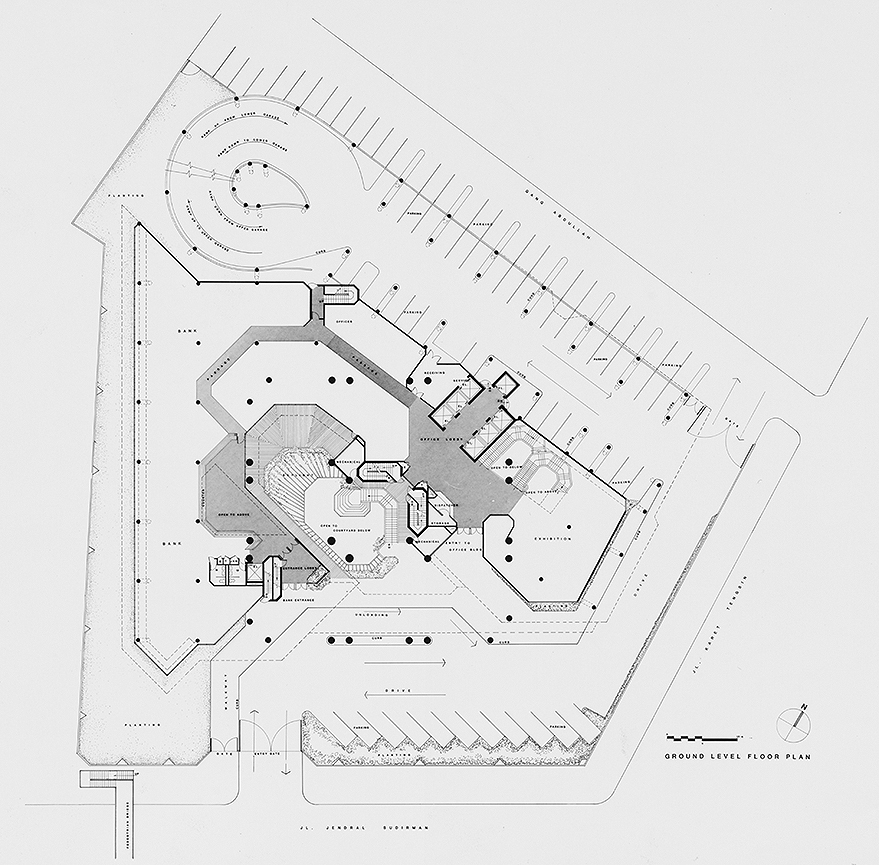

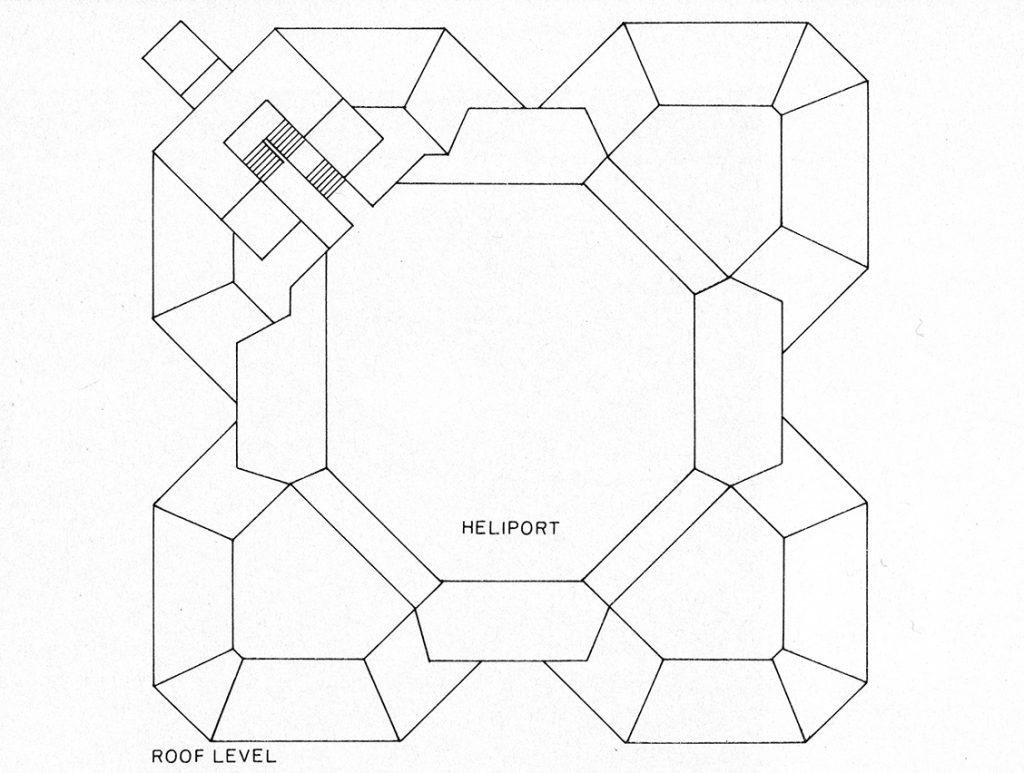

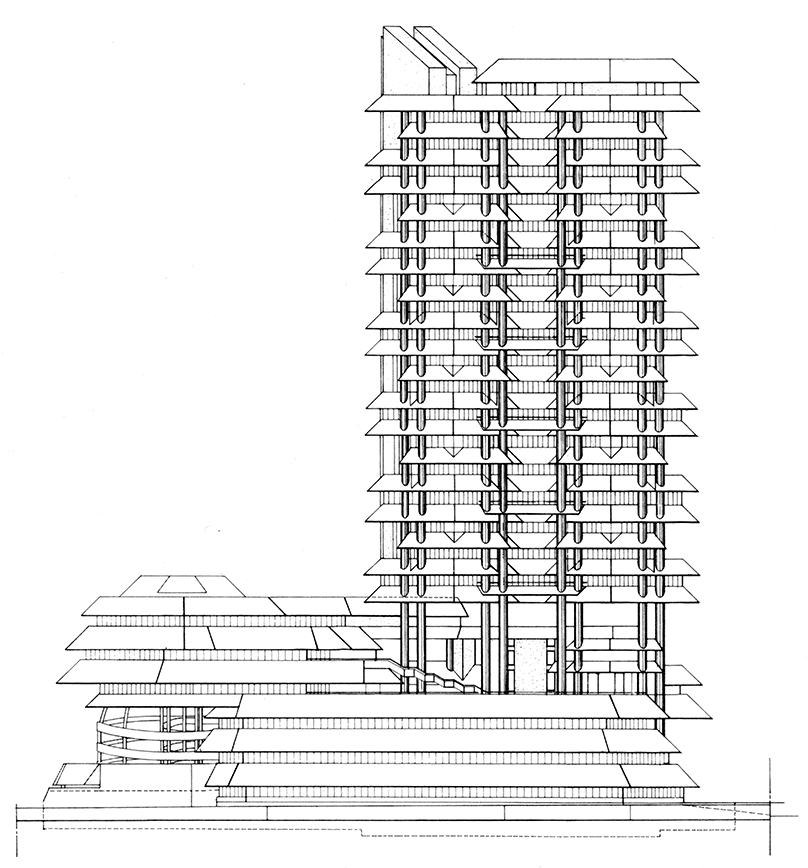

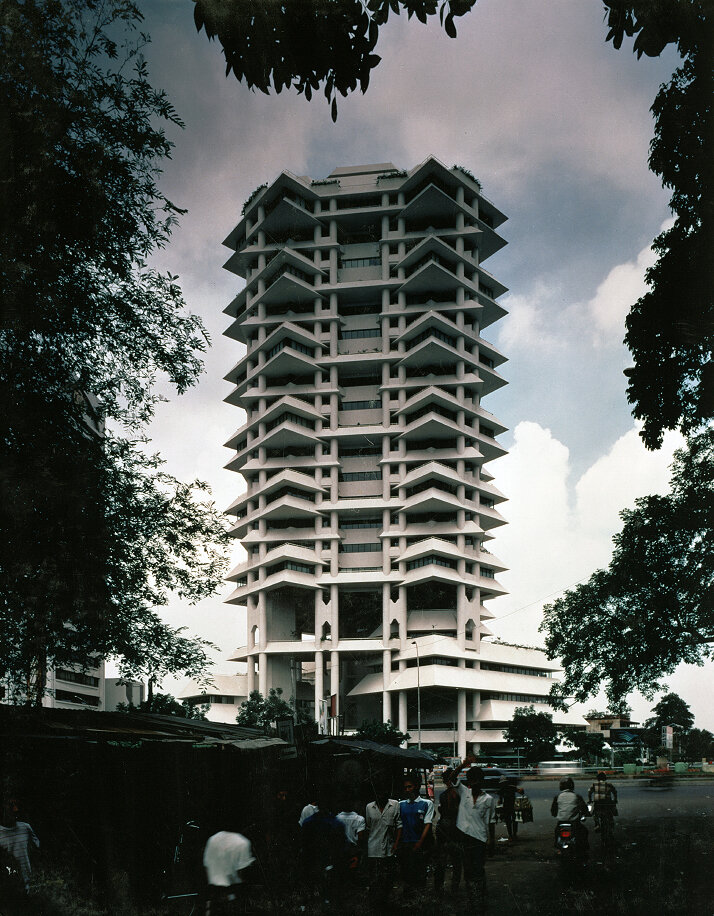

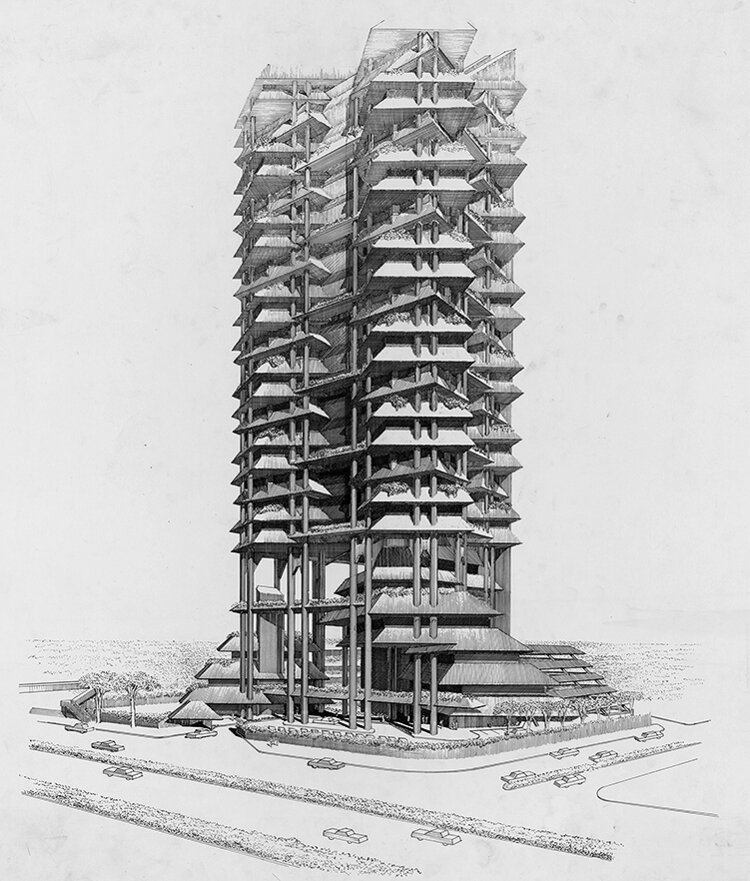

A final building in Southeast Asia, the Dharmala Headquarters, in Jakarta, in many ways brings into sharp focus a number of longstanding issues in the work of Paul Rudolph. Perhaps because this building, unlike the others he did in Southeast Asia, was not a speculative building but the headquarters for one of Indonesia’s largest companies (a trading group on the Japanese model), the architect had a somewhat freer hand. The complex contains some of the same elements seen in his other buildings in Southeast Asia, indeed in almost every large Rudolph complex since the 1960s, but the elements are all more elaborated. There is the tower, here even more intricately modeled than in any previous example, the podium containing garage, exhibition space, and bank, and the open courtyard giving access to all parts of the complex.

Finalmente, otro edificio en el sudeste asiático son las Oficinas Dharmala en Jakarta, que, de muchas maneras trata, la mayoría de los temas en los que trabajaba Paul Rudolph. Quizás poorque este edificio, a diferencia de otros que él hizo en el Sudeste Asiático, no era un edificio especulátivo sino las oficinas para una gran compañía (un gran empresa japonesa), el arquitecto tuvo más libertad. El complejo contiene algunos de los mimsmos elementos que sus otros proyectos en esta región, de hecho en casi todos los grandes proyectos de Rudolph desde la década de 1960. En este caso, la torre está intrínsicamente mejor modelada, el podium acoge un garaje, un espacio de exposición y el patio abierto que da acceso a todo el complejo.

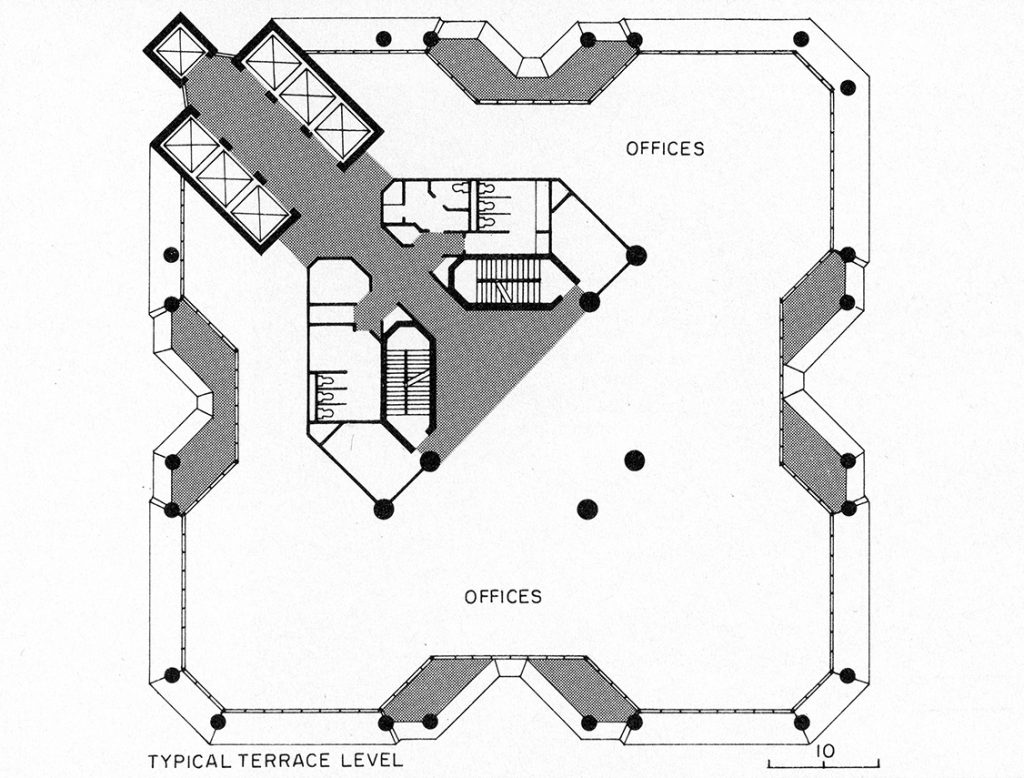

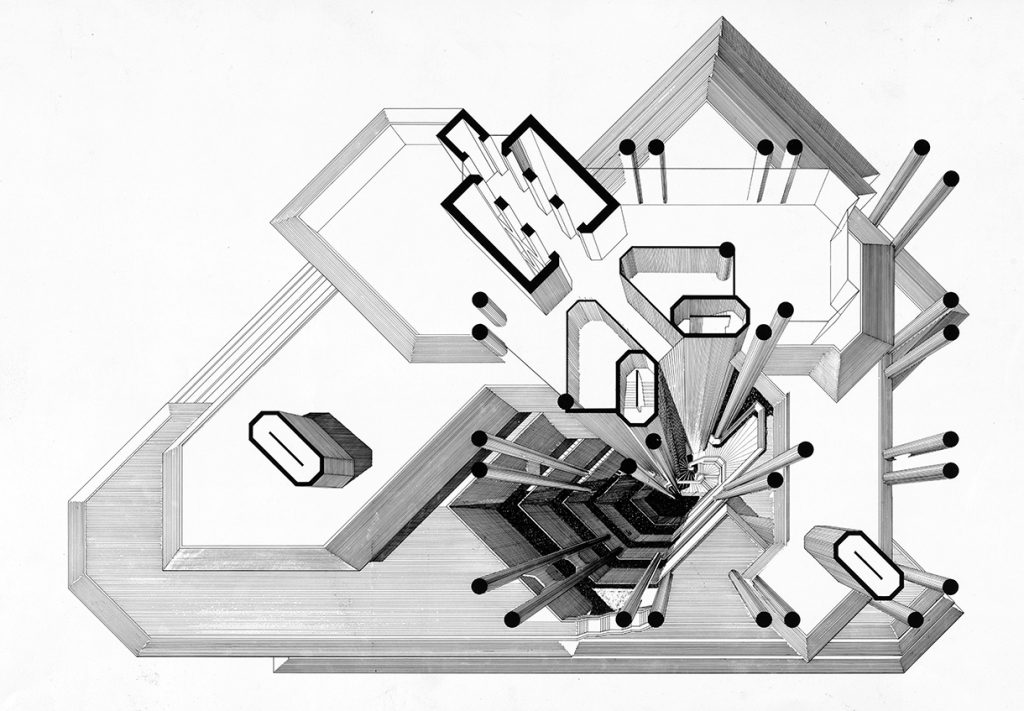

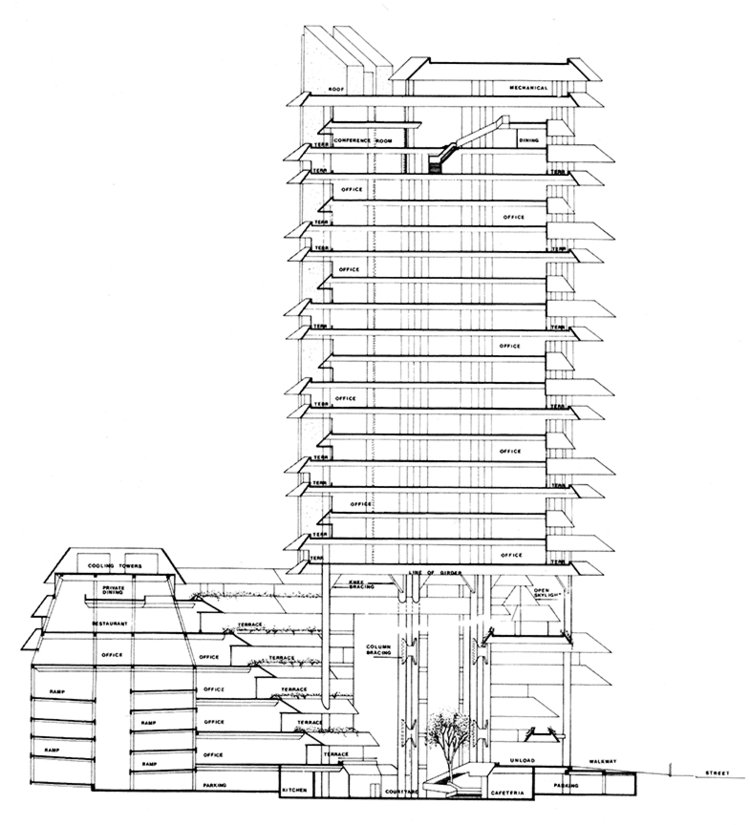

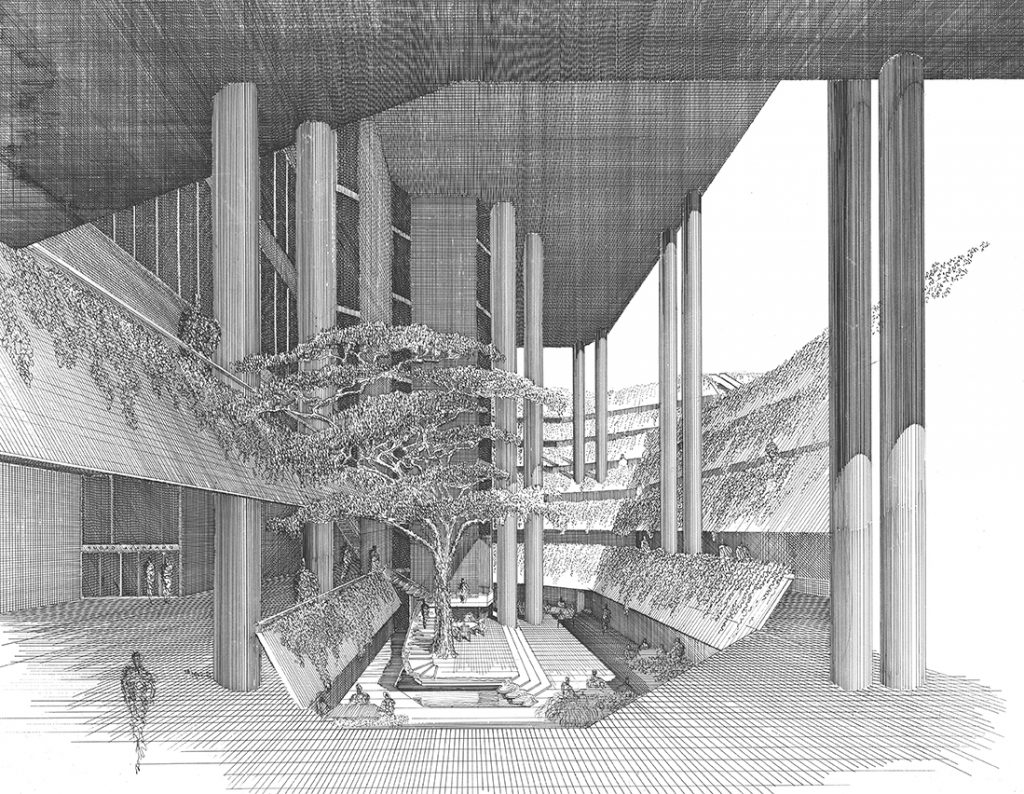

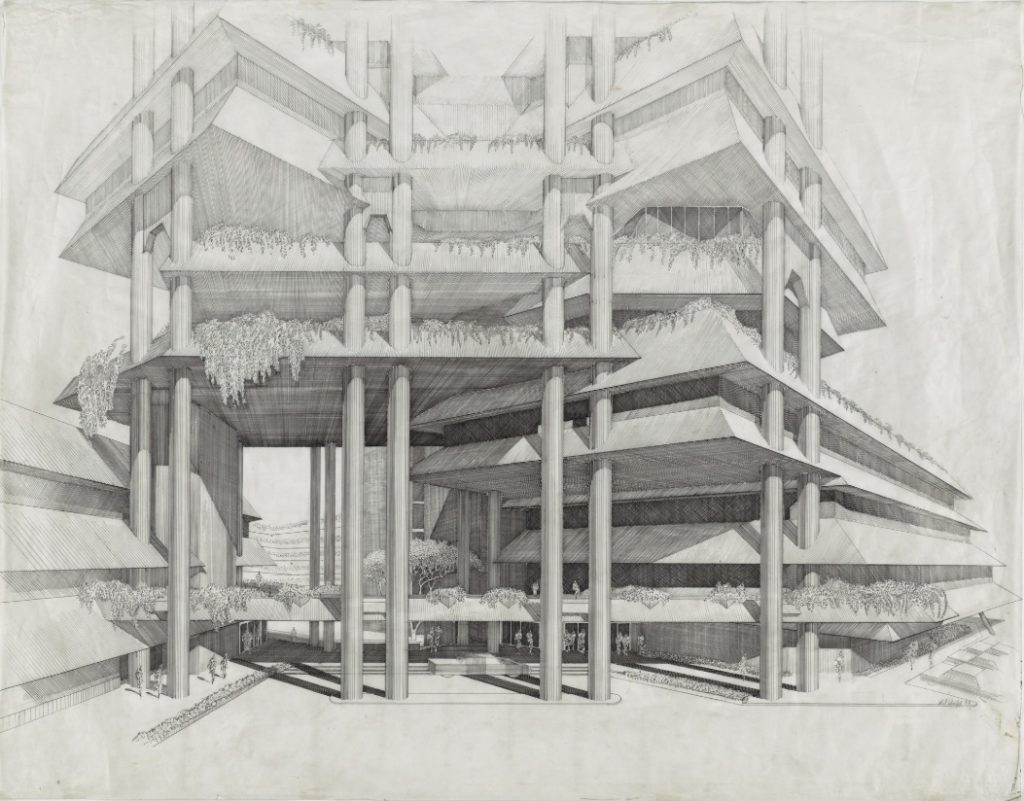

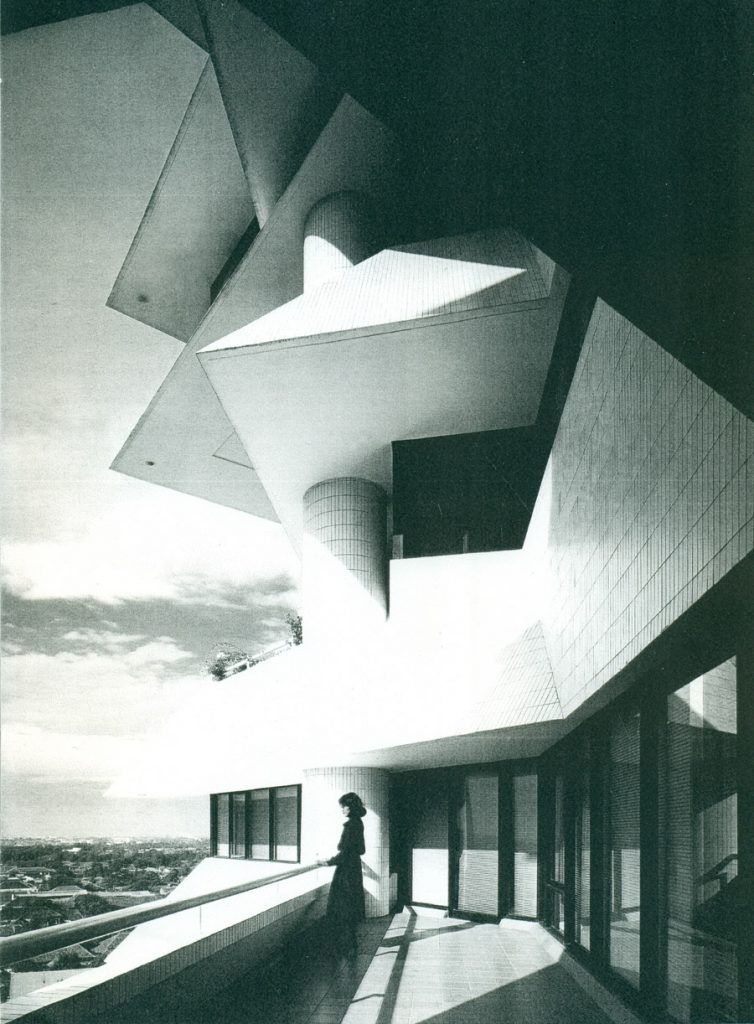

What is different in Jakarta is the setting. Jakarta, unlike Singapore or Hong Kong or any other city in which Rudolph had built, was the capital of a developing country. The Dharmala Building is located along the Jalan Sudriman, an enormous, heavily traveled street that is part boulevard and part expressway and that connects the old core of Jakarta with a ring road around the central district. Although the street is lined almost solidly with Western-style commercial high-rises, a visitor to the complex can still see within a few hundred yards of the boulevard the low wood structures, many without running water or plumbing, that constitute the majority of the building stock in the city. The Rudolph building, along with its neighbors, is a First World monument grafted onto the building stock of a Third World city. For reasons of climate and security, the architect pulled the entire ensemble inward, mounding the low buildings around the courtyard and placing the tower over the terrace to shade it. At each level the courtyard steps back, creating terraces for the offices in the base of the complex. Waterfalls and canals and vines cascading from the terraces create a secure, shaded tropical paradise at the center of the complex’s podium, which contains offices, parking and special-function areas.

Lo que es diferente en Yakarta es el entorno. A diferencia de Singapur, Hong Kong, u otra ciudad en la que Rudolph había construido, ésta ciudad era la capital de un país en desarrollo. El Edificio Dharmala está ubicado a lo largo de Jalan Sudriman, una gran calle, muy transitada, que es en parte bulevar y en parte autopista, y que conecta el antiguo núcleo de Yakarta con una carretera de circunvalación alrededor del distrito central. Aunque la calle está bordeada casi en su totalidad por rascacielos comerciales de estilo occidental, el visitante aún puede ver, en unas zonas del bulevar, las estructuras bajas de madera, muchas sin agua corriente ni tuberías, que constituyen la mayoría de la ciudad. El edificio deRudolp, junto con las construcciones adyacentes, es un monumento del Primer Mundo injertado en una ciudad del Tercer Mundo. Por razones de clima y seguridad, el arquitecto empujó todo el conjunto hacia adentro, aglutinó los edificios bajos alrededor del patio y colocó la torre sobre la terraza para sombrearla. En cada nivel, el patio retrocede, creando terrazas para las oficinas en la base del complejo. Las cascadas, los canales y las vides que caen en cascada desde las terrazas crean un paraíso tropical seguro y sombreado en el centro del podio del complejo, que contiene oficinas, estacionamientos y otras áreas.

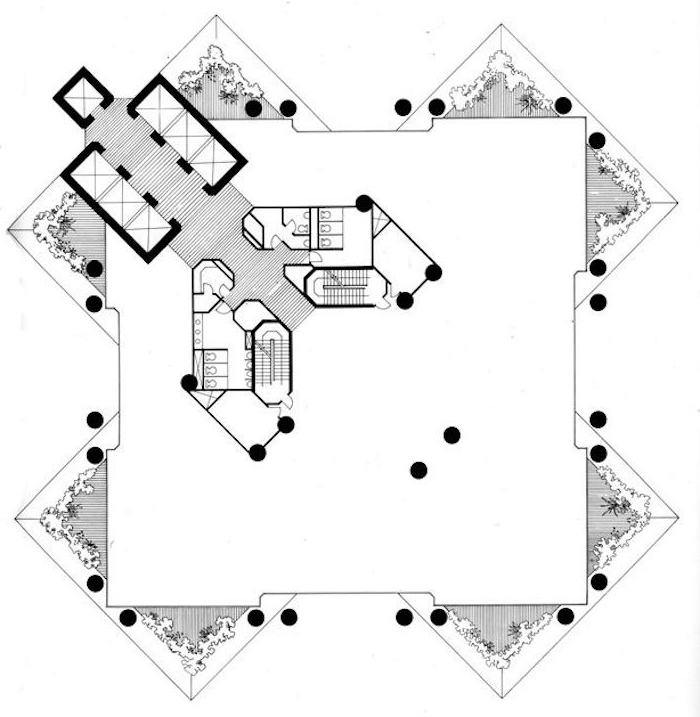

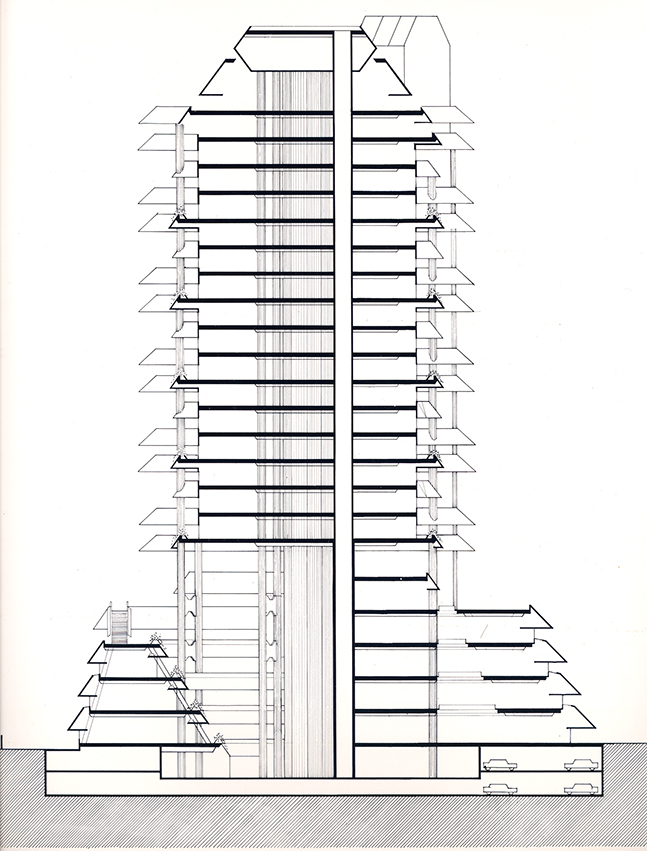

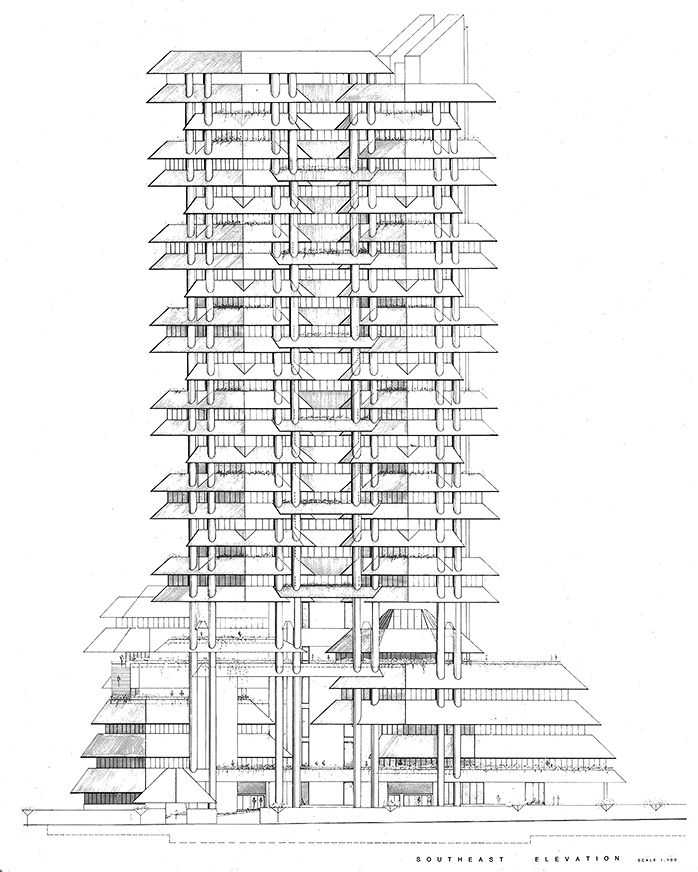

The most conspicuous aspect of the Dharmala tower, the sloping roofs that shade the floors underneath them, was likewise an explicit response to local climate and to traditional Indonesian architecture. Rudolph’s study of this architecture was neither scholarly nor scientific. He learned about it largely through visits to an outdoor architectural museum. What impressed him most, amid the staggering variety of forms visible in the vernacular buildings, was the consistency in the shapes of the overhanging roofs. Constructed to put important functional spaces in shadow and to accelerate the flow of hot air up and out, the roofs impressed him as the chief elements in a regional vernacular architecture of considerable beauty. At Dharmala, Rudolph abstracted the roof forms and combined them with his own interest in rotated geometry and the interplay between supporting elements and building perimeter. Held aloft by great paired columns, the tower starts at about thirty meters above grade level, the columns rising through a series of rotated floor plates that create overhanging roofs at each level. These overhangs shield the windows below and provide outdoor terraces for the offices. The architect’s drawings suggest that he envisioned the entire building as a kind of hanging garden, with trees and bushes planted in the terraces and vines cascading down the side. In fact, more than any other urban building by Rudolph, the Dharmala complex suggests his ideas about the way architecture and landscape can merge.

El aspecto más llamativo de la torre Dharmala, los techos inclinados que dan sombra a los pisos debajo de ellos, fue también una respuesta explícita al clima local y a la arquitectura tradicional de indonesia. El estudio de Rudolph sobre esta arquitectura no fue académico ni científico. Lo aprendió en gran medida a través de visitas a un museo de arquitectura al aire libre. Lo que más le impresionó, en medio de la asombrosa variedad de formas visibles en los edificios vernáculos, fue la consistencia en las formas de los techos. Construido para poner espacios funcionales importantes en la sombra y para acelerar el flujo de aire caliente hacia arriba y hacia afuera, los techos lo impresionaron como los elementos principales en una arquitectura regional vernácula de considerable belleza. En Dharmala, Rudolph abstrajo las formas del techo y las combinó con su propio interés en la geometría rotada y la interacción entre los elementos de soporte y el perímetro del edificio. Sostenida en alto por grandes columnas emparejadas, la torre comienza a unos treinta metros sobre el nivel del suelo. Las columnas se elevan a través de una serie de losas rotadas que crean techos sobresalientes en cada nivel. Estos voladizos protegen las ventanas de abajo y proporcionan terrazas al aire libre para las oficinas. Los dibujos del arquitecto sugieren que él imaginó todo el edificio como una especie de jardín colgante, con árboles y arbustos plantados en las terrazas y enredaderas en cascada a un lado. De hecho, más que cualquier otro edificio urbano de Rudolph, el complejo Dharmala sugiere sus ideas sobre la forma en que la arquitectura y el paisaje pueden fusionarse.

Bruegmann, Robert. (February 2010). The Architect as Urbanist: Part 2 Paul Rudolph’s late work in Singapore from placesjournal.org

All Drawings by Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation