This article is part of Infrastructural Urbanism, a series curated by Hidden Architecture where we explore the evolutionary potential over time of certain urban and architectural structures. The infrastructural nature of these projects allows them to accommodate and assume the uncertainty of future development as a project tool.

Este articulo es parte de Urbanismo Infraestructural, serie que explora el potencial evolutivo a lo largo del tiempo de determinadas estructuras urbanas y arquitectónicas. El carácter de infraestructura de estos proyectos les permite albergar y asumir la incertidumbre de un desarrollo futuro como herramienta de proyecto.

***

“The construction of West Village transforms the idea of everyday leisure into a collective expression of monumental scale, functioning as a vibrant recreational center for neighboring communities, as well as fostering the construction of a complex environment with vitality and potential for growth.”

“La construcción de West Village transforma la idea de ocio del día a día en una expresión colectiva de escala monumental, funcionando como un vibrante centro recreativo para las comunidades vecinas, así como fomentando la construcción de un entorno complejo, con vitalidad y potencial de crecimiento.”

Jiu Liakun

Context

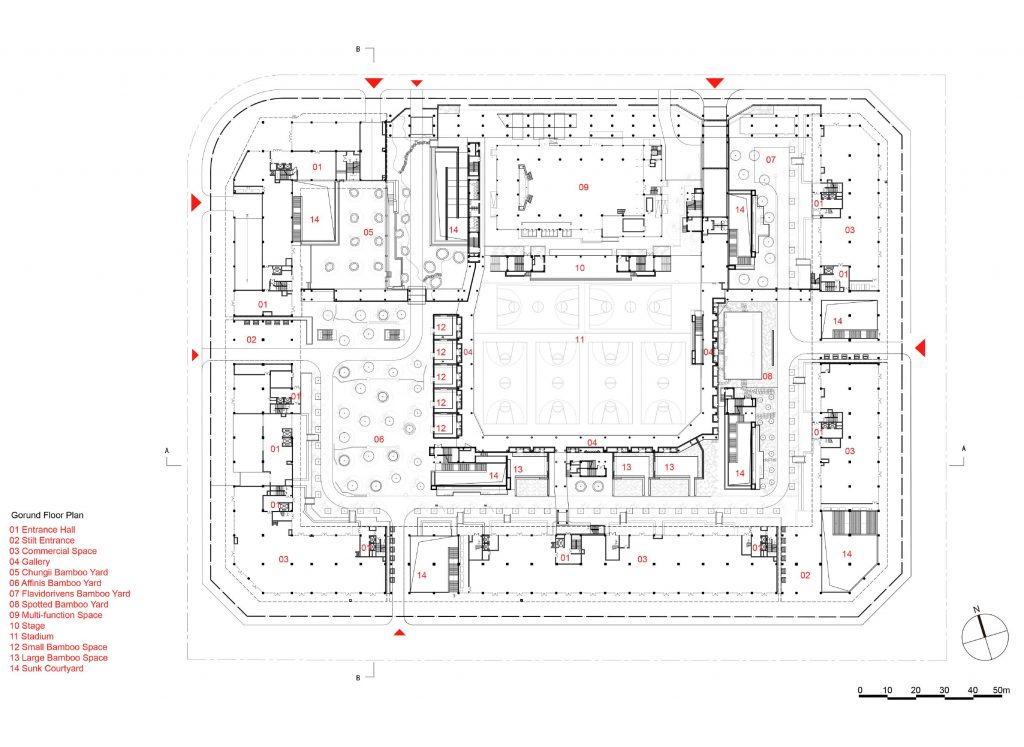

The city of Chengdu, with a population of almost 20 million, is the capital of the Sichuan region, located in the southwest of the People’s Republic of China. Despite its ancient origins, there are hardly any traces left of any period prior to the second half of the 20th century, when the application of late socialism was mixed with rapid capitalist economic development, a specific circumstance that determines the characteristic urban identity of most large Chinese cities. One of the main consequences of this model is a radical break with Chinese cultural and urban tradition, a phenomenon that is particularly evident in a crisis of the idea of collectivity linked to the urban community space. The West Village project, carried out by the office of architect Liu Jiakun, is located in an urban environment that responds to this situation. Located west of the city of Chengdu, the original plot where the project was to be developed was quite large: 278 x 178 meters. This urban void had some pre-existing features, such as an indoor swimming pool that was retained at the request of the developer, with its intended use being auxiliary sports facilities for the neighboring residential communities. The maintenance of the pre-existing building, located on the northern edge of the plot, was fundamental, as will be explained later, in defining one of the fundamental spatial axes of the West Village urban complex.

La ciudad de Chengdu, con casi 20 millones de habitantes, es la capital de la región de Sichuan, situada en el sudoeste de la República Popular China. A pesar de su origen milenario, apenas quedan vestigios de ninguna época anterior a la segunda mitad del siglo XX, donde la aplicación de un socialismo tardío se mezcla con un desarrollo económico capitalista muy acelerado, circunstancia específica que determina la característica identidad urbana de la mayoría de grandes ciudades chinas. Una de las principales consecuencias de este modelo es la ruptura radical con la tradición cultural y urbana china, fenómeno que se aprecia notablemente en una crisis de la idea de colectividad vinculada al espacio urbano comunitario. El proyecto de West Village, ejecutado por la oficina del arquitecto Liu Jiakun, se localiza en un entorno urbano que responde a esta casuística. Situado al oeste de la ciudad de Chengdu, la parcela original donde debía desarrollarse el proyecto tenía unas dimensiones considerables: 278 x 178 metros. Este vacío urbano contaba con alguna preexistencia, como una piscina cubierta que se mantuvo a petición del promotor, siendo su uso previsto instalaciones deportivas auxiliares para las comunidades residenciales vecinas. El mantenimiento del edificio preexistente, emplazado en el límite norte de la parcela, fue fundamental, como se explicará más adelante, para definir uno de los ejes espaciales fundamentales del conjunto urbano de West Village.

Like most urban units that make up the city of Chengdu, the area surrounding Liu Jiakun’s project is characterized by a high-density fabric, where tall residential towers are organized into large superblocks. At first glance, the dimensions of the residential plots are very similar to those where the West Village project was built. Between them, roads, many of them elevated, reinforce a certain idea of urban isolation for each of these superblocks. Within the urban perimeter formed by these towers or residential blocks, a series of residual open spaces, with little or no urban quality, make up the open fabric in which citizens move between their residential space and the urban mobility infrastructure. The main challenge of Liu Jiakun’s project, and also its greatest virtue, will be to redefine the idea of collective urban space as an expression of community. The success of this radical approach, in contrast to the surrounding urban context, is the fundamental value of West Village.

Como la mayoría de las unidades urbanas que componen la ciudad de Chengdu, el área circundante al proyecto de Liu Jiakun se caracteriza por un tejido de alta densidad, donde altas torres de viviendas se organizan en grandes supermanzanas. A simple vista, las dimensiones de las parcelas de uso residencial son muy similares a aquella donde se asentó el proyecto de West Village. Entre ellas, viarios de circulación rodada, muchos de ellos elevados, refuerzan una cierta idea de aislamiento urbano para cada una de estas supermanzanas. En el interior del perímetro urbano que componen estas torres o bloques residenciales, una serie de espacios abiertos residuales, de escasa o nula cualidad urbana, componen el tejido abierto en el que los ciudadanos transitan entre su espacio de residencia y las infraestructuras urbanas de movilidad. El desafío principal del proyecto de Liu Jiakun, y también su mayor virtud, será redefinir la idea de espacio urbano colectivo como expresión de una comunidad. El éxito de este radical planteamiento, en contraposición al contexto urbano que lo rodea, es el valor fundamental de West Village.

References

Liu Jiakun’s project is a stimulating materialization of the idea of an urban courtyard, on a large scale and defined by a perimeter block, as a megastructure. However, the origin of the characteristic urban morphology of a perimeter block with an interior courtyard, so foreign to the Chinese urban landscape, had little to do with a theoretical approach or positioning. On the contrary, the strategy of defining the edge of the urban plot with a perimeter block, leaving a huge courtyard inside, arose from various volumetric and urban studies carried out by the architect with the aim of optimizing urban regulations to the maximum. Given that the plot was intended for community sports facilities, both the permitted height and the volume, area, and occupancy of the plot were relatively small, at least when compared to the urban environment full of large towers and apartment blocks, where building density is extraordinarily high. In such a context, where empty space for collective use is unusual, Liu Jiakun opted to align the commercial blocks with the road, accentuating the urban character of the West Village proposal. This left a large interior void, protected from the urban aggressiveness dominated by road traffic, so that all kinds of collective urban activities and events could be developed. As a result of this stance, which we could define as appropriately pragmatic, a large urban courtyard was created for collective use, bordered by a commercial block, which acts as a great condenser of collective activity: the West Village megastructure.

El proyecto de Liu Jiakun es una estimulante materialización de la idea de patio urbano, a gran escala y definido por un bloque perimetral, como megaestructura. Sin embargo, el origen de la característica morfología urbana de bloque perimetral con patio interior, tan ajena en el paisaje urbano chino, poco tuvo que ver con un planteamiento o posicionamiento teórico. Por el contrario, la estrategia de definir el borde de la parcela urbana con un bloque perimetral, dejando en su interior un patio de enormes dimensiones, surgió de diferentes estudios volumétricos y urbanos realizados por el arquitecto con el objetivo de optimizar al máximo las regulaciones urbanas. Teniendo en cuenta que el uso de la parcela estaba destinado a equipamientos deportivos comunitarios, tanto la altura permitida, como el volumen, el área y la ocupación de la parcela tenían valores relativamente pequeños, al menos si se compara con el entorno urbano plagado de grandes torres y bloques de viviendas, donde la densidad edificatoria es extraordinariamente elevada. En un contexto así, donde el espacio vacío de uso colectivo no es habitual, Liu Jiakun apostó por la alineación de los bloques comerciales al viario, acentuando el carácter urbano de la propuesta del West Village. De esta manera, se dejaba un gran vacío interior, protegido de la agresividad urbana dominada por el tráfico rodado, para que se pudieran desarrollar todo tipo de actividades y acontecimientos urbanos de carácter colectivo. Como resultado de esta postura, que podríamos definir como acertadamente pragmática, se definió el gran patio urbano, de uso colectivo y delimitado por un bloque comercial, que actúa como un gran condensador de actividad colectiva: la megaestructura de West Village.

In the particular Chinese context, whether in contemporary manifestations or in traditional architecture, it is unusual to find similar models of perimeter buildings enclosing a courtyard, especially those intended for collective use and open to the public. On the other hand, their relationship with European urban tradition seems evident. The West Village urban block fills the plot it occupies, bringing intensity to the surrounding streets and thus defining, both programmatically and formally, the city’s public roads in a continuous and uninterrupted manner. The large communal courtyard, measuring 182 x 137 meters, offers the citizens of Chengdu a space where they can carry out all kinds of leisure activities.

En el particular contexto chino, ya sea en manifestaciones contemporáneas o también en la arquitectura tradicional, no es habitual encontrar modelos similares de edificios perimetrales que encierran un patio, especialmente de vocación colectiva y abiertos al público. Por otro lado, su relación con la tradición urbana europea parece evidente. El bloque urbano de West Village colmata la parcela que ocupa, aportando intensidad al viario circundante y definiendo así, tanto programática como formalmente, el viario público de la ciudad de forma continua e ininterrumpida. El gran patio colectivo, con unas dimensiones de 182 x 137 metros, ofrece a los ciudadanos de Chengdu un espacio donde llevar a cabo todo tipo de actividades vinculadas con el ocio.

His understanding of the city is linked to the tradition of European urban planning during the Enlightenment, which led to the development of urban expansion plans. These plans had the dual objective of improving the sanitary conditions of homes and interior spaces, on the one hand, and defining a continuous public space, on the other, where the idea of control and, at the same time, the manifestation of the power of modern states, were very much present. In paradigmatic cases such as the Barcelona Expansion, designed by Idelfons Cerda, the dimensions of the urban blocks reach the minimum threshold at which it is possible to glimpse the transition from the private courtyard model to other more complex hybrids, in which these spaces are opened up and collectivized through the appearance of gardens, commercial spaces, or facilities within the blocks.

Su forma de entender la ciudad tiene vinculaciones con la tradición del urbanismo europeo de la Ilustración, momento a partir del cual se desarrollan los planes de Ensanches urbanos. Estos tuvieron el doble objetivo de mejorar las condiciones de salubridad de las viviendas y espacios interiores, por un lado, y de definir un espacio público continuo, por el otro, donde la idea de control y , al mismo tiempo, la manifestación del poder de los Estados Modernos, estaban muy presentes. En casos paradigmáticos como el Ensanche de Barcelona, obra de Idelfons Cerda, las dimensiones de los bloques urbanos alcanzan el umbral mínimo en el que es posible vislumbrar la transición desde el modelo de patio privado a otros híbridos y más complejos, en los que se efectúa una apertura y colectivización de esos espacios, mediante la aparición de jardines, espacios comerciales o equipamientos en el interior de las manzanas.

The urban planning of the Modern Movement, whose principles were vehemently defined during the various editions of the CIAM Congresses and the drafting of the Athens Charter, categorically rejected the value of the perimeter urban block and the idea of the street as a linear and continuous public space, opting instead for the construction of free-standing blocks on open, green but undefined spaces, crisscrossed by roads. The scope of these principles, together with their link to an ultra-capitalist model of urban development, where buildable land is nothing more than a market commodity, are clearly visible in today’s cities, especially in China. In recent decades, attempts have been made to return to the collective values of the traditional city, especially through a formal approach not without revisionist and conservative nostalgia. In this area, we can find a multitude of urban projects in cities such as Vienna, Barcelona, and Berlin, to name just a few examples, which seek to recover the idea of the courtyard as the center of urban life, linked to the definition of streets by perimeter blocks. In line with some of these projects, where a considerable increase in the scale of urban courtyards has led to their evolution into models of urban megastructures brimming with activity, we could include Liu Jiakun’s West Village project.

El urbanismo del Movimiento Moderno, cuyos postulados se definieron con vehemencia durante las distintas ediciones de los Congresos CIAM y la redacción de la Carta de Atenas, negó rotundamente el valor del bloque urbano perimetral y la idea de la calle como un espacio público lineal y continuo, apostando por la construcción de bloques libres sobre un espacio abierto, verde pero indefinido, surcado por vias de comunicacion. El alcance de estos postulados, junto a su vinculación con un modelo de desarrollo urbano ultracapitalista, donde el suelo edificable no es más que un producto de mercado, son bien visibles en las ciudades de nuestros días, especialmente en China. En las últimas décadas se ha intentado retornar a los valores colectivos de la ciudad tradicional, especialmente mediante una aproximación formal no exenta de nostalgia revisionista y conservadora. En este ámbito podríamos encontrar multitud de proyectos urbanos, en ciudades como Viena, Barcelona o Berlín, por citar solo unos ejemplos, donde se pretende recuperar la idea de patio como centro de la vida urbana, vinculada a la definición de las calles mediante bloques perimetrales. En la línea de algunos de ellos, donde un aumento de escala considerable en las dimensiones de los patios urbanos los hace evolucionar hacia modelos de megaestructuras urbanas cargadas de actividad, se podría afiliar el proyecto de West Village de Liu Jiakun.

On the other hand, we can also find different types of Chinese architectural traditions that West Village may be indebted to, both in terms of its formal and operational approaches. Closer in time, many of them still in use and fully valid, we would find the Work Units (Danwei Dayuan), which function as almost self-sufficient urban nodes around work centers. The urban form they can take is variable, but they all consist of a series of buildings that bring together community services and housing around factories or workshops. To reinforce the expressiveness of the collective idea of work, many of them are made up of different linear blocks articulated around open spaces, where the work centers are located, which in turn define the operational and control center of these urban units. During the decades of growth of the People’s Republic of China, these Work Units were an element of urban growth and the generation of fundamental social and political identity. Liu Jiakun’s goal in designing the West Village project was to express the power of the idea of collectivity by constructing an urban monument, an urban megastructure in the form of a large public courtyard. In this respect, his intentions ran parallel to those mandated by the planners of the Work Units, although certainly with a different ideological approach.

Por otro lado, podemos encontrar también en la tradición arquitectónica China diferentes tipologías de las que West Village puede ser deudora, tanto en sus planteamientos formales como operativos. Más próximas en el tiempo, muchas de ellas todavía en uso y plena vigencia, nos encontraríamos con las Unidades de Trabajo (Danwei Dayuan), que funcionan como nodos urbanos casi autosuficientes en torno a centros de trabajo. La forma urbana que pueden tomar es variable, pero todas se componen de una serie de edificaciones que aglutinan servicios comunitarios y viviendas en torno a fábricas o talleres. Para reforzar la expresividad de la idea colectiva del trabajo, muchas de ellas se constituyen de diferentes bloques lineales articulados alrededor de espacios abiertos, donde se localizan los centros de trabajo, que definen a su vez el centro operativo y de control de estas unidades urbanas. Durante las décadas de crecimiento de la República Popular China, estas Unidades de Trabajo fueron un elemento de crecimiento urbano y generación de identidad social y política fundamental. El objetivo de Liu Jiakun al diseñar el proyecto de West Village fue expresar la fuerza de la idea de colectividad mediante la construcción de un monumento urbano, de una megaestructura urbana en forma de gran patio público. En este aspecto, sus intenciones transcurrían en paralelo a aquellas que los planificadores de las Unidades de Trabajo tenían como mandato, aunque seguramente con un enfoque ideológico diferente.

A modern, honest, and direct expression, with brutalist influences, together with the boldness of its urban form, do not reveal, at first glance, any clear connections with traditional Chinese architecture. However, various authors have pointed out certain aspects that should be taken into account and which, once outlined, enrich the possible interpretations or genealogies of West Village. Firstly, it should be noted that, although the courtyard element is not abundant in the Chinese context in terms of urban fabric or residential typologies—with the exception of the Tulous in the Fujian region—it is common to find numerous examples of this typology in temples or imperial complexes. If we take the Forbidden City in Beijing as an example, we can see that the basic unit that articulates the extensive complex is the courtyard, in multiple scales, functions, and forms. In addition, there is an element that gives coherence to each of these courtyards in the imperial residence complex: a linear organizing axis that always defines the main route. We can also interpret that the West Village complex is governed by this principle. As already mentioned, before starting the project, Liu Jiakun encountered a pre-existing structure on the urban plot: an old indoor swimming pool that the developer wanted to preserve and convert into a multifunctional hall. This nondescript building, however, becomes a fundamental element in the urban complex. On the one hand, it is a historical witness to the collective memory of the city, which is maintained, preserved, and reused to give value to the heritage received from the socialist era. At the organizational level, this volume, located in the middle of the north side of the plot, defines a north-south axis that organizes the main access to the West Village courtyard. The perimeter block that houses the commercial uses occupies the remaining three sides of the plot, embracing the old swimming pool and adopting a C-shaped block form. On the north side, bypassing the existing building, a series of ramps are arranged that rise to reach different levels of the perimeter block, constructing a monumental access portico on their ascent that defines this organizing axis towards the interior of the courtyard.

Una expresión moderna, honesta y directa, de ascendencia brutalista, junto a la rotundidad de su forma urbana no evidencian, a simple vista, relaciones claras con la tradición popular China en materia de arquitectura. Sin embargo, diversos autores han señalado algunos aspectos que conviene tener en cuenta y que, una vez esbozados, enriquecen las posibles interpretaciones o genealogías de West Village. En primer lugar, es necesario reseñar que, a pesar de que en la construcción del tejido urbano o en las tipologías residenciales el elemento patio no abunde en el contexto chino – a excepción de los Tulous en la región de Fujian – , es habitual encontrar numerosos ejemplos de esta tipología en templos o conjuntos imperiales. Si tomamos como ejemplo la Ciudad Prohibida de Beijing, observaremos que la unidad elemental que articula el extenso conjunto es el patio, en múltiples escalas, funciones y formas. Además, existe un elemento que da coherencia a cada uno de estos patios en el conjunto de la residencia imperial: un eje ordenador lineal que define siempre el recorrido principal. Podemos interpretar, asimismo, que el conjunto del West Village se rige también por este principio. Como ya se ha comentado, antes de iniciar el proyecto, Liu Jiakun se encontró con un preexistencia en la parcela urbana: una antigua piscina cubierta que el promotor quería conservar y convertir en sala multifuncional. Este edificio anodino se convierte, sin embargo, en un elemento fundamental en el conjunto urbano. Por un lado, es un testigo histórico de la memoria colectiva de la ciudad, que se mantiene, conserva y reutiliza para dar valor a la herencia recibida de la etapa socialista. A nivel organizador, este volumen, situado en la mitad de la cara norte de la parcela, define un eje norte-sur que organiza el acceso principal al patio de West Village. El bloque perimetral que acoge los usos comerciales ocupa los tres lados restantes de la parcela, abrazando la antigua piscina y adoptando una forma de bloque en C. En la cara norte, salvando el edificio preexistente, se disponen una serie de rampas que se elevan para alcanzar diferentes niveles del bloque perimetral, construyendo en su ascenso un pórtico monumental de acceso que define este eje ordenador hacia el interior del patio.

It is possible to point out some other aspects that link the West Village project with China’s popular heritage. After the existence of this linear organizing axis, surely the next in importance is the concept of separation, generating small environmental units or microcosms. At first glance, the coexistence of this principle with the previous one, that of an organizing axis, seems impossible due to pure contradiction. However, architect Liu Jiakun has been able to combine the two in a well-ordered conjunction, defining the basis that generates the functional and spatial richness of West Village. As already mentioned, the organizing axis defines the volume of the perimeter block and the direction of the main access, determining its mainly urban character of openness to the city. On the other hand, the vast interior space, the large collective courtyard, is divided into countless rooms and areas with different functions, offering a complex tapestry of circumstances. This way of interpreting the city’s public space is fundamental in the Chinese tradition, where the articulation and compartmentalization of small areas predominate, composing an autonomous unit or microcosm, where at no time is there a global vision or idea of the whole. To understand this particular way of composing the urban fabric, it is pertinent to compare it with some examples of European cities mentioned above, where since the Renaissance urban space has been designed based on an idea of overall composition and harmony, where the idea of perspective and total perception of the whole, linked to the manifestation of different powers, is fundamental.

Es posible señalar algunos aspectos más que vinculan el proyecto de West Village con la herencia popular China. Después de la existencia de este eje ordenador lineal, seguramente el siguiente en relevancia sea el concepto de separación generando pequeñas unidades ambientales o microcosmos. A simple vista, la coexistencia de este principio con el anterior, el de un eje ordenador, parece imposible por pura contradicción. Sin embargo, el arquitecto Liu Jiakun ha sido capaz de combinar los dos, en una bien ordenada conjunción, definiendo la base que genera la riqueza funcional y espacial de West Village. Como ya se ha comentado, el eje ordenador define la volumetría del bloque perimetral y la dirección de acceso principal, determinando su carácter principalmente urbano de apertura a la ciudad. Por otro lado, el vasto espacio interior, el gran patio colectivo, se articula en innumerables estancias y recintos con funciones diferentes, ofreciendo un complejo tapiz de circunstancias. Esta forma de interpretar el espacio público de la ciudad es fundamental en la tradición china, donde predominan la articulación y compartimentación de pequeños recintos componiendo una unidad o microcosmos autónomo, donde en ningún momento se tiene una visión o idea global del conjunto. Para entender esta particular forma de componer el tejido urbano, es pertinente compararla con algunos ejemplos de ciudades europeas que antes hemos citado, donde desde el Renacimiento el espacio urbano se diseña desde una idea de composicion y armonia global, donde la idea de perspectiva y percepción total del conjunto, vinculado a la manifestación de los distintos poderes, es fundamental.

Similar to a Hutong, a traditional Chinese residential neighborhood, the West Village courtyard is composed of small spatial units with different uses, which are connected to each other along the route. When composing this idea of separate enclosures, architect Liu Jiakun draws on another element from tradition: the bamboo forest. Thus, the combination of these tree masses with walls and uneven surfaces constructs and articulates the urban courtyard of West Village, linking this collective manifestation of modern China with part of its popular tradition that, unfortunately, the progress of recent decades has been eliminating. Despite the emphatic manifestation of its urban form, together with its considerable dimensions, from inside the courtyard, at ground level, the scale of the spaces is rather domestic. Far from being a manifestation of collectivity linked to power, it more accurately evokes the idea of small communities that make up a larger order from a similar hierarchical position. Only by ascending the ramp system and reaching the upper levels do we obtain a global, almost panoramic view of the West Village complex. The contrast between elements from the Modern Movement tradition, such as the ramp system, and Chinese popular culture is a constant that lends a complex richness of nuance to Liu Jiakun’s project.

Al igual que en un Hutong, tipología de barrio residencial tradicional chino, el patio de West Village se compone a partir de pequeñas unidades espaciales con diferentes usos, que se van conectando entre sí a través del recorrido. A la hora de componer esta idea de recintos separados, el arquitecto Liu Jiakun recurre a otro elemento procedente de la tradición: el bosque de bambú. Así, la combinación de estas masas arbóreas con muros y desniveles construye y articula el patio urbano de West Village, vinculando esta manifestación colectiva de la China moderna con parte de su tradición popular que, por desgracia, el progreso de las últimas décadas ha ido eliminando. A pesar de la rotunda manifestación de su forma urbana, junto a unas dimensiones considerables, desde el interior del patio, a nivel de suelo, la escala de los espacios es más bien doméstica. Lejos de una manifestación de colectividad vinculada al poder, evoca con más acierto la idea de pequeñas comunidades que componen un orden mayor desde una posición jerárquica similar. Solo al ascender por el sistema de rampas y alcanzar, desde su trazado, los niveles superiores, obtenemos una visión global, casi panorámica, del conjunto de West Village. La contraposición entre elementos procedentes de la tradición del Movimiento Moderno, como es el sistema de rampas, y la cultura popular china es una constante que otorga una compleja riqueza de matices al proyecto de Liu Jiakun.

Finally, there are other concepts derived from traditional Chinese architecture that are very present in the definition of the West Village. As mentioned above, courtyards are not common in Chinese culture, but the existence of large open squares that allow for fluid and diverse routes is certainly anomalous. On the contrary, in Chinese cities, public space is linear, rarely centripetal in nature, and its scale is, in any case, very different from the large collective spaces found in other regions of the world. The large courtyard in West Village attempts, in principle, to refute this approach. However, the articulation and separation that takes place at ground level means that this central space, rather than becoming a fluid place capable of accommodating a large crowd simultaneously, functions as a microcosm of small, interconnected spaces. When activated by some kind of event, their character manifests itself, from an urban point of view, as closed and exclusive to other types of functions. Thus, the West Village’s public spaces for meeting and spontaneous activity will be the ascending walkways, the elevated levels, and the linear galleries, both interior and exterior, of the perimeter block. In their almost cloistered layout, surrounding the courtyard in multiple ways and with different routes, they define a linear public space of a collective nature.

Por último, existen otros conceptos procedentes de la arquitectura tradicional china que se encuentran muy presentes en la definición del West Village. Como se ha comentado, la existencia de patios no es habitual en la cultura China, pero desde luego la existencia de grandes plazas abiertas, que permitan recorridos fluidos y diversos, es del todo anómala. Por el contrario, en las ciudades chinas puede apreciarse que el espacio público es lineal, que en raras ocasiones adquiere un carácter centrípeto y su escala se encuentra, en todo caso, muy alejada de los grandes espacios colectivos de otras regiones del planeta. El gran patio de West Village intenta, en principio, desmentir este planteamiento. Sin embargo, la articulación y separación que se lleva a cabo a nivel de suelo provoca que este espacio central, antes que de convertirse en un lugar fluido y capaz de albergar una gran multitud simultáneamente, funcione como un microcosmos de pequeños espacios concatenados. Cuando están activados por algún tipo de acontecimiento, su carácter se manifiesta, desde un punto de vista urbano, como cerrado y excluyente respecto a otro tipo de función. De esta forma serán las pasarelas de ascenso, los niveles elevados y, además, las galerías lineales, interiores y exteriores, del bloque perimetral, los espacios públicos de encuentro y actividad espontánea del West Village. En su trazado casi claustral, rodeando el patio de múltiples maneras y con distintos recorridos, definen un espacio público lineal de carácter colectivo.

Operative Strategies

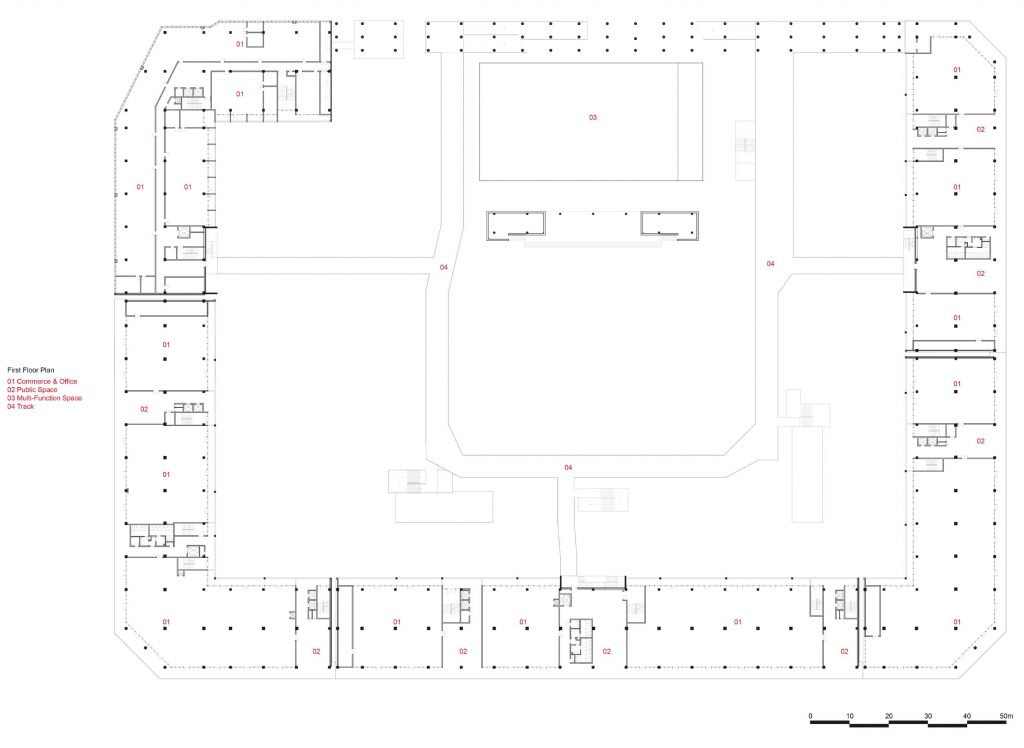

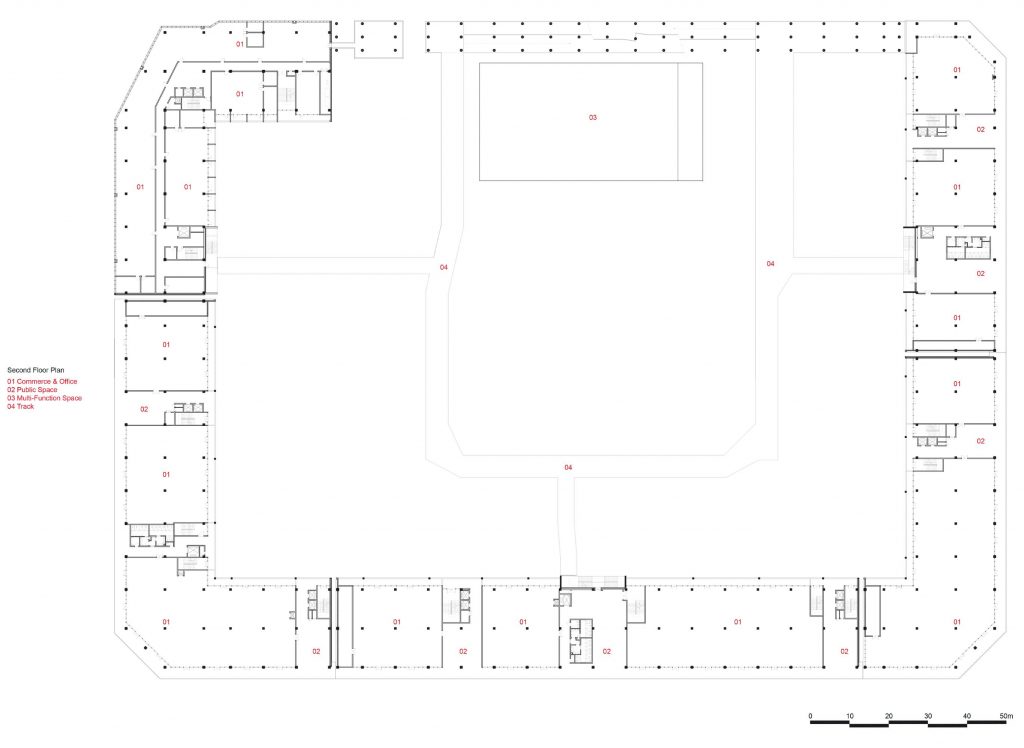

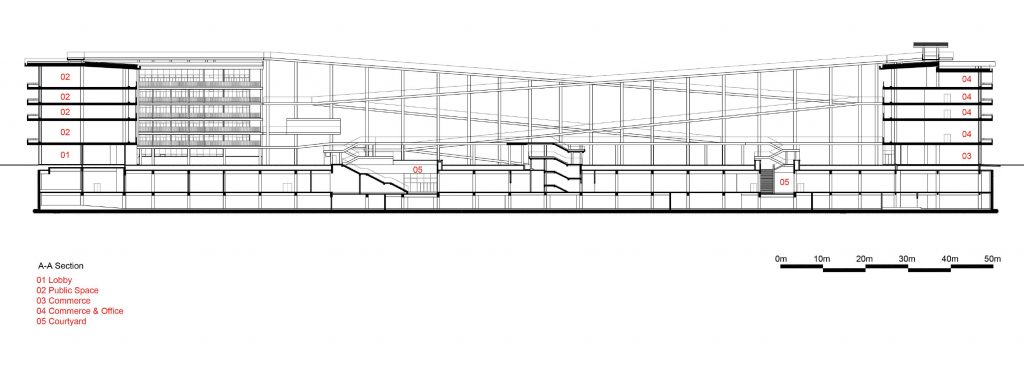

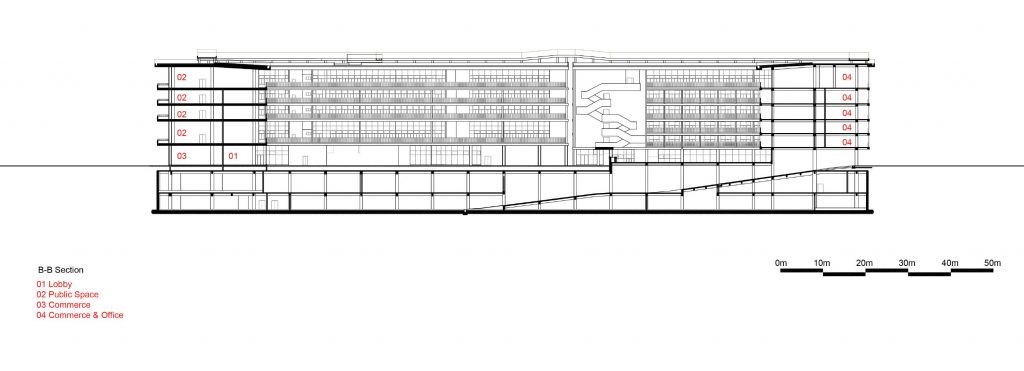

The large courtyard in West Village houses various outdoor sports facilities, as well as restaurants, leisure and cultural venues, and simply places to stroll. Meanwhile, the perimeter blocks, which serve as a support and boundary for the sports courts with respect to the city of Chengdu, are home to various commercial and office uses. In contrast to the spatial complexity and variety of uses offered by the open courtyard space, the perimeter blocks display a neutrality of language that reinforces their character as urban support. Their composition as architectural elements is simple, pragmatic, and focused on offering the greatest possible degree of flexibility of use and versatility of programs. Each of the three arms that make up the perimeter block has a constant bay width of almost 20 meters, with three rows of pillars in the central part and continuous linear galleries cantilevered three meters wide on each side, both inside the courtyard and facing the city. The structure, built in serial concrete, is only interrupted by the different stairwells, which connect each of the levels, through the perimeter galleries, directly to the courtyard level. It can be said that the perimeter block is the first manifestation of the infrastructural nature of Liu Jiakun’s project. Far from any formal or linguistic rhetoric, beyond the tectonics of the materials used, it is conceived with the aim of becoming a neutral, homogeneous support capable of accepting and enhancing the mutability of functions.

El gran patio de West Village acoge diferentes espacios de uso deportivo al aire libre, así como locales de restauración, ocio, culturales o sencillamente de paseo. Por otro lado, los bloques perimetrales, que ejercen de soporte y delimitador de las pistas deportivas respecto a la ciudad de Chengdu, albergan diferentes usos comerciales y oficinas. Frente a la complejidad espacial y la variedad de usos que ofrece el espacio abierto del patio, los bloques perimetrales manifiestan una neutralidad de lenguaje que refuerza su carácter de soporte urbano. Su composición como elementos arquitectónicos es sencilla, pragmática y está enfocada a ofrecer el mayor grado posible de flexibilidad de uso y polivalencia de programas. Cada uno de los tres brazos que componen el bloque perimetral presentan una crujía constante de casi 20 metros de anchura, con tres ejes de pilares en la parte central y unas galerías lineales continuas en voladizo de tres metros de ancho a cada lado, tanto al interior del patio como volcadas a la ciudad. La estructura, ejecutada en hormigón de forma seriada, se ve solo interrumpida por los diferentes núcleos de escaleras, que comunican cada uno de los niveles, a través de las galerías perimetrales, directamente con el nivel del patio. Se puede afirmar que el bloque perimetral implica la primera manifestación del carácter infraestructural del proyecto de Liu Jiakun. Lejos de cualquier retórica formal o lingüística, más allá de la propia tectónica de los materiales empleados, se concibe con el objetivo de convertirse en un soporte neutro, homogéneo y capaz de aceptar y potenciar la mutabilidad de funciones.

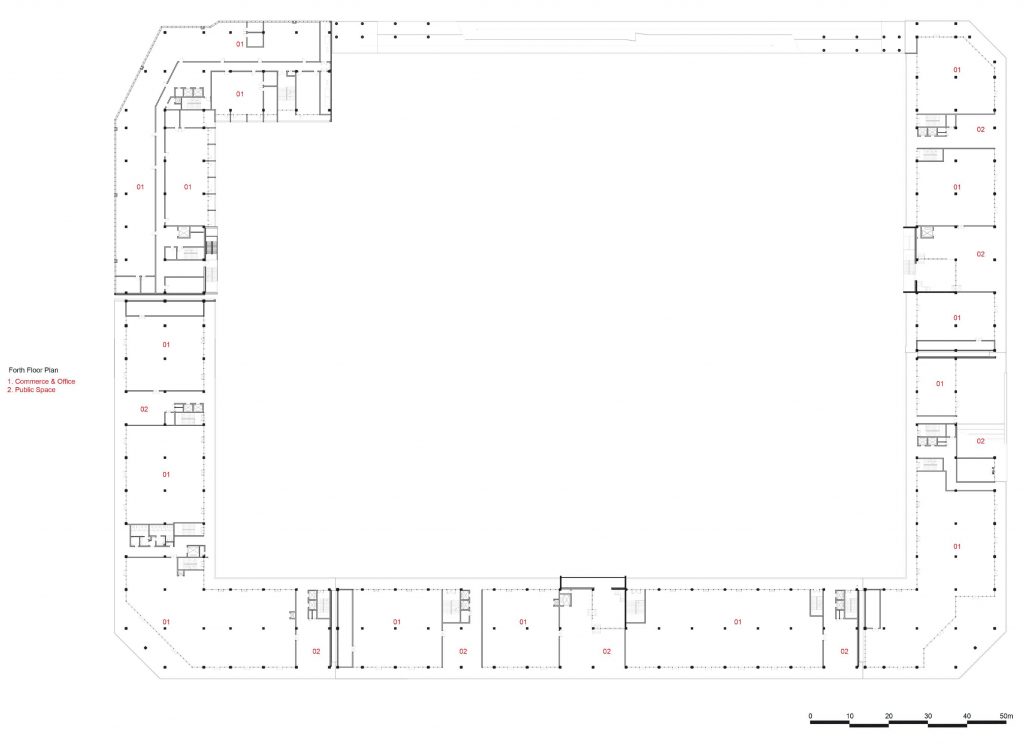

While Liu Jiakun wanted to offer a homogeneous floor plan, with a constant module defining the West Village courtyard on each of its sides, the project’s sectional approach differs from this idea. Due to the urban regulations for the plot, the maximum height allowed above ground level was 24 meters. Instead of trying to obtain the maximum number of floors within this height limit, reducing the clear height to a minimum, another option was chosen where the heights of the floors differed from each other, achieving some with greater clear height in exchange for having only five floors above ground level. The reason for this decision is, once again, a pragmatic approach on the part of the architect. Instead of ensuring equal conditions for all levels, which was essential in the floor plan, the decision was made to give the most commercially profitable floors—the first, second, and fifth—greater headroom. In this way, the developer achieves greater profitability on the most valuable floors. This apparent contradiction, however, presents an interesting opportunity within the interpretation of the West Village as an infrastructure project. The floors with the lowest ceiling height—the third and fourth, at 3.70 meters—do not seem to offer much possibility for variability in their use. However, the project anticipates the possibility that on the floors with the highest ceiling height—5.70 meters—users will build double-height spaces, a situation that would completely alter the functioning and density of each unit. The fact that the project itself offers the possibility, or even promotes the emergence of these probable potentials, and assumes that these changes will take place beyond the architect’s control, significantly reinforces the idea of the project as an infrastructural support.

Si Liu Jiakun quería ofrecer un trazado en planta homogénea, con una módulo constante que definiera el patio de West Village en cada una de sus caras, el planteamiento del proyecto en sección difiere de esta idea. Debido a las regulaciones urbanísticas de la parcela, la altura máxima permitida sobre rasante era de 24 metros. En lugar de tratar de obtener el máximo número de plantas dentro de este límite de altura, reduciendo la altura libre al mínimo, se optó por otra opción donde las alturas de las plantas difirieran entre sí, consiguiendo algunas con mayor altura libre a cambio de tener solo cinco plantas sobre rasante. La razón de esta decisión responde, una vez más, a un posicionamiento pragmático del arquitecto. En lugar de garantizar la igualdad de condiciones para todos los niveles, anhelo que era esencial en el trazado en planta, se opta por plantear las plantas que son comercialmente más rentables – la primera, segunda y quinta – con una altura libre mayor. De esta forma, el promotor consigue una rentabilidad mayor en las plantas más valiosas. Esta aparente contradicción presenta, sin embargo, un escenario de oportunidad interesante dentro de la interpretación del West Village como un proyecto de naturaleza infraestructural. Las plantas cuya altura libre menor – la tercera y la cuarta, con 3,70 metros – no parecen ofrecer muchas posibilidades de variabilidad en su uso. Sin embargo, se prevé desde el proyecto la posibilidad de que en las plantas con mayor altura libre – 5,70 metros – los usuarios construyan dobles alturas, situación que alteraría por completo el funcionamiento y densidad de cada unidad. El hecho de ofrecer la posibilidad, o incluso promover el surgimiento de estas probables potencialidades, desde el propio proyecto, y asumir que estas mutaciones se llevarán a cabo lejos del control del arquitecto, refuerza notablemente la idea del proyecto como un soporte infraestructural.

The intention to delegate part of the control over decisions regarding the final appearance of the building to the users themselves appears again, even more clearly, in the design of the urban facades that the West Village perimeter block displays towards the city of Chengdu, both towards the street and towards the large courtyard. The idea of horizontality, which contrasts sharply with the urban context dominated by tall vertical towers, is strongly determined by the formalization of the building’s envelope. Three-meter cantilevered galleries completely surround the project’s volume, defining a linear space for circulation and interaction that is cloistered in the case of the interior gallery and panoramic in the case of the exterior gallery. The dominant presence of these galleries, reinforced by a massive concrete parapet, constitutes a relatively abstract and neutral image of horizontal development. The support function, within an interpretation of the building as infrastructural, is thus achieved with the definition of a first order, that is, the structural framework. However, at this point, the problem of enclosing the interior spaces has not been resolved. During the design process, Liu Jiakun carried out various studies of patterns for enclosing the premises. Far from finding a satisfactory proposal, he opted to let users, behind the homogeneous appearance of the structural support, have the option of deciding how they wanted to compose and decorate the façade of their premises, obviously within the limits of coherence within the project. As with the variable height section of the different floors, the introduction of a second order, in this case also controlled by the end users of the building, enables open and change-responsive operation, which translates into a mutable and vibrant image of the idea of collectivity.

La intención de delegar parte del control de decisiones sobre el aspecto final del edificio a los propios usuarios aparece de nuevo, todavía de manera más clara, en la concepción de las fachadas urbanas que, tanto hacia la calle como hacia el gran patio, el bloque perimetral de West Village despliega hacia la ciudad de Chengdu. La idea de horizontalidad, que tanto contrasta con el contexto urbano dominado por altas torres verticales, está fuertemente determinada por la formalización de la envolvente del volumen. Las galerías en voladizo de tres metros rodean por completo el volumen del proyecto, definiendo un espacio lineal de circulación e interacción de carácter claustral, en el caso de la galería interior, y panorámico, en el caso de la exterior. La presencia dominante de estas galerías, reforzada por un peto de hormigón masivo, constituye una imagen relativamente abstracta y neutra de desarrollo horizontal. La función de soporte, dentro de un interpretación del edificio como infraestructural, se consigue así con la definición de un primer orden, esto es, el entramado estructural. Sin embargo, hasta este punto no ha quedado resuelto el problema del cerramiento de los espacios interiores. En el proceso de diseño, Liu Jiakun realizó diversos estudios de patrones para el cerramiento de los locales. Lejos de encontrar una propuesta satisfactoria, optó por dejar que los usuarios, detrás de la apariencia homogénea del soporte estructural, tuvieran la opción de decidir cómo querían componer y decorar la fachada de su local, obviamente dentro de unos límites de coherencia dentro del proyecto. Al igual que sucedía con la sección variable en altura de las distintas plantas, la introducción de un segundo orden, en este caso también controlado por los usuarios finales del edificio, posibilita una operatividad abierta y receptiva al cambio, lo que se traduce en una imagen mutable y vibrante de la idea de colectividad.

In this conception of the building’s enclosure—ultimately, the threshold of physical exchange with the city—the prominence of the interior and exterior galleries is evident. In addition to the operational value they add to the functioning and spatiality of the complex, these elements of transition between interior and exterior are fundamental to the West Village’s relationship with Chinese folk tradition. Looking closely at almost any example of popular architecture, it is possible to see that a direct transition between an interior space and public space is rarely made. Moreover, in many cases, there is not even a direct visual connection, but rather the visual relationship between the private interior and the collective exterior is also produced through intermediate transitional elements or spaces. Despite a volumetry—and infrastructural character—that is entirely indebted to Modernism, Liu Jiakun’s West Village subtly ensures, through the use of these perimeter galleries, that the relationship between exteriors and interiors, even visually, is carried out through at least one transitional space.

En esta concepción del cerramiento del edificio – en definitiva, el umbral de intercambio físico con la ciudad – es evidente el protagonismo de las galerías interiores y exteriores. Además del valor operativo que añaden al funcionamiento y espacialidad del conjunto, estos elementos de transición entre interior y exterior son fundamentales en la relación del West Village con la tradición popular china. Observando con detenimiento casi cualquier ejemplo de arquitectura popular, es posible apreciar que en rara ocasión se realiza una transición directa entre un espacio interior y el espacio público. Es más, en muchas ocasiones, ni siquiera existe una conexión visual directa, sino que la relación visual entre interior privado y exterior colectivo se produce también a través de elementos o espacios intermedios de transición. A pesar de una volumetría – y carácter infraestructural de soporte – completamente deudora de la Modernidad, el West Village de Liu Jiakun garantiza con sutileza, mediante el empleo de estas galerías perimetrales, que la relación entre exteriores e interiores, incluso visualmente, se lleva a cabo a través de, al menos, un espacio de transición.

Finally, it is necessary to highlight the importance of these perimeter galleries, not only as elements of circulation, activation of functions, and transition between interior and exterior, but also as elements of infrastructural value in anchoring the project to its urban environment. As mentioned above, the north façade of West Village, which preserves the existing building, becomes the main façade as it marks the organizing axis of the complex. In this spatial and compositional operation, the layout of the different sections of ramp is fundamental. Surrounding and rising above the existing building, they define a monumental entrance portico. While this idea of an organizing axis was not easily discernible on the ground floor, due to the microcosm of environmental units proposed, it is on the first level where it is most clearly manifested. By designing an elevated gallery with a ring-shaped geometry, the north-south axis is defined by the volume of the ramps. This elevated circulation system connects the ramps with the three bodies of the perimeter block, ensuring fluid circulation over the large courtyard. However, the dimensions and hierarchy of this elevated gallery transcend a mere distributive function. On the contrary, they will be fundamental in activating each of the levels and orientations of the interior facades, hosting all kinds of activities that may arise spontaneously. While the street level of the large West Village courtyard maintains a dialogue with popular Chinese spatial tradition through a strategy of fragmentation, the level of elevated galleries and ramps is modern, open, and infrastructural in nature. As the culmination of this spatial system, the ramps ascend to the roof of the perimeter blocks, tracing a linear panoramic route. In this way, West Village users move from the introspection of an articulated and protected ground floor to the exposure and total openness to the urban context that occurs at roof level.

Por último, es necesario señalar la importancia de estas galerías perimetrales no solo como elementos de circulación, activación de funciones y, además, elementos de transición entre interior y exterior, sino también como elementos de valor infraestructural en el arraigo del proyecto con su entorno urbano. Como se ha comentado anteriormente, la fachada norte de West Village, aquella que conserva el edificio preexistente, se convierte en la fachada principal al trazar desde ella el eje ordenador del conjunto. En esta operación espacial y compositiva es fundamental el trazado de los diferentes tramos de rampa que, rodeando y elevándose sobre la preexistencia, definen un pórtico de acceso de carácter monumental. Si en planta baja esta idea del eje ordenador no era fácilmente discernible, debido al microcosmos de unidades ambientales propuesto, es en primer nivel donde se materializa con rotundidad. Mediante el trazado de una galería elevada de geometría anular, el eje norte-sur queda definido desde el volumen de las rampas. Este sistema de circulación elevado conecta las rampas con los tres cuerpos del bloque perimetral, garantizando unas circulaciones fluidas sobre el patio de grandes dimensiones. Sin embargo, las dimensiones y jerarquía de esta galería elevada trascienden una mera función distribuidora. Por el contrario, serán fundamentales para activar cada uno de los niveles y orientaciones de las fachadas interiores, albergando todo tipo de actividades que espontáneamente puedan surgir. Si el nivel de calle del gran patio de West Village mantiene un diálogo con la tradición espacial popular china a partir de una estrategia de fragmentación, el nivel de galerías y rampas elevadas es de una naturaleza moderna, abierta e infraestructural. Como culminación de este sistema espacial, las rampas ascienden hasta la cubierta de los bloques perimetrales, trazando en ella un recorrido panorámico lineal. De esta forma, el usuario de West Village transita desde la introspección de una planta baja articulada y protegida, a la exposición y apertura total al contexto urbano que sucede a nivel de cubierta.

Infrastructural Nature

Liu Jiakun’s West Village project has a high capacity to accommodate and, more importantly, promote and encourage countless urban and social activities. Its infrastructural nature is not only evident in this aspect, but especially in its ability to embrace and integrate uncertainty, the mutability of unforeseen future events.

El proyecto de West Village de Liu Jiakun dispone de una alta capacidad de albergar y, lo que es más importante, potenciar e incitar innumerables actividades urbanas y sociales. Su carácter infraestructural no se manifiesta solo en esta naturaleza, sino especialmente en su capacidad de asumir e integrar la incertidumbre, la mutabilidad de los acontecimientos futuros imprevistos.

West Village is essentially composed of two basic units. On the one hand, there is the perimeter block which, together with the ramp structure and the existing building, delimits the urban plot, continuously defining the surrounding urban road network. On the other hand, there is the large urban courtyard enclosed within the perimeter block. Each of these elements manifests its infrastructural nature in a different way, but they complement each other to articulate a hub of urban activity in a densely populated neighborhood.

West Village está compuesto, esencialmente, de dos unidades elementales. Por un lado, el bloque perimetral que, junto al cuerpo de rampas y el edificio preexistente, delimitan la parcela urbana definiendo el viario urbano circundante de manera continua. Por otro lado, el gran patio urbano delimitado en el interior del bloque perimetral. Cada uno de estos elementos manifiesta su naturaleza infraestructural de forma diferente, pero se complementan para articular un nodo de actividad urbana en un barrio densamente poblado.

The perimeter block serves as a support for the establishment and development of multiple commercial activities, designed to fill the large courtyard with users and activity. Architect Liu Jiakun worked from the outset with the idea of support to define this element, with the clear intention of establishing an operational framework from which users could develop a certain degree of freedom in occupying the space. To this end, different levels of control are established. First, the primary order is constituted by the basic infrastructure of the block, which is controlled by the planning team. However, with the aim of enabling users to develop different strategies for occupying and settling in the space, the architectural support itself allows for the possibility of future changes without compromising the primary order. In this second order, users assume certain levels of control, being able to occupy high-rise spaces with intermediate levels or define the enclosures to the outside of the spaces they rent.

El bloque perimetral funciona como un soporte para el asentamiento y evolución de múltiples actividades comerciales, destinadas a cargar de usuarios y actividad el gran patio. El arquitecto Liu Jiakun trabajó desde el principio con la idea de soporte para definir este elemento, con la clara intención de establecer un marco operativo a partir del cual los usuarios pudieran desarrollar un determinado grado de libertad en la ocupación del espacio. Para ello, se establecen diferentes niveles de control. En primer lugar, el orden primario queda constituido por la infraestructura básica del bloque, siendo controlado por el equipo de planeamiento. Sin embargo, con el objetivo de hacer que los usuarios pudieran desarrollar diferentes estrategias de habitación y asentamiento, el propio soporte arquitectónico permite la posibilidad de albergar mutaciones futuras sin que el primer orden quede comprometido. En este segundo orden, los usuarios asumen ciertos niveles de control, pudiendo ocupar espacios de gran altura con niveles intermedios o definir los cerramientos al exterior de los espacios que alquilan.

Liu Jiakun’s ambition was to turn his West Village project into a public monument to the idea of collectivity. However, this monument was not to be a dead, embalmed space. On the contrary, it was to be an active urban hub. For this reason, he was aware from the outset of the project that in order to honestly express the idea of collectivity, it was necessary to cede part of the responsibility for its definition to the users themselves. In other words, users should not feel like passive agents in the large courtyard of West Village, but rather active agents in its spatial configuration, as well as key players in defining the collective identity of the new space.

La ambición de Liu Jiakun era convertir su proyecto de West Village en un monumento público a la idea colectividad. Sin embargo, este monumento no debía ser un espacio muerto, embalsamado. Al contrario, debía constituir un activo nodo urbano. Por esta razón, fue consciente, desde el principio del proyecto, de que para expresar honestamente la idea de colectividad era necesario ceder parte de la responsabilidad en su definición a los propios usuarios. Es decir, los usuarios no deben sentirse solo agentes pasivos del gran patio de West Village, sino que debían ser agentes activos en la configuración espacial del mismo, además de convertirse en actores fundamentales en la definición de la identidad colectiva del nuevo espacio.

The second element of the project, the large urban courtyard, is fundamental to the construction of the West Village’s collective identity. Due to its capacity to promote different urban activities and the spatial complexity with which it is articulated, the large courtyard defines its infrastructural nature insofar as it connects with the surrounding urban fabric, activating an important area of Chengdu that until then lacked quality public spaces. Its supporting nature is manifested in different ways. On the one hand, the spatial articulation characteristic of its ground level, linked to Chinese popular tradition and the concept of separation of spaces, weaves a complex spatial framework that embraces the complexity, difference, mutability, and simultaneity of multiple urban events. In addition, the expressive emphasis given to the treatment of circulation elements, such as galleries and ramps connecting the large courtyard to the perimeter block, transforms these elements, and especially the ground-level areas where these interactions take place, into active supports of an infrastructural nature.

En la construcción de la identidad colectiva de West Village es fundamental el segundo elemento que integra el proyecto: el gran patio urbano. Por su capacidad de fomentar diferentes actividades urbanas y la complejidad espacial con la que se articula, el gran patio define su naturaleza infraestructural en la medida en que se conecta con el tejido urbano circundante, activando una importante área de Chengdu que hasta entonces carecía de espacios públicos de calidad. Su naturaleza de soporte se manifiesta en diferentes sentidos. Por un lado, la articulación espacial característica de su nivel de suelo, vinculada con la tradición popular china y el concepto de separación de espacios, teje un complejo marco espacial que asume la complejidad, la diferencia, la mutabilidad y la simultaneidad de múltiples acontecimientos urbanos. Además, el énfasis expresivo que recibe el tratamiento de los elementos de circulación, como galerías y rampas que conectan el gran patio con el bloque perimetral, transforman estos elementos, y especialmente las regiones del nivel de suelo donde se producen estas interacciones, en activos soportes de naturaleza infraestructural.