This article is part of Ungreen, a series curated by Hidden Architecture where we attempt to create a resistance against some of the dogmas assimilated within contemporary discourse that sustainable architecture has to be “green”. We want to recover the ancestral knowledge that was shared among generations throughout history of humanity and defines how urban settlements have adapted to its weather conditions.This knowledge, inherent to vernacular architecture has been often used by modern or contemporary architectural practices to create new techniques or construction systems.

Este artículo es parte de Ungreen, una serie comisariada por Hidden Architecture donde tratamos de crear una resistencia contra algunos de los dogmas asimilados en el discurso actual que claman que la arquitectura sostenible tiene que ser verde. Queremos recuperar el conocimiento ancestral que ha sido heredado a través de generaciones a lo largo de la historia de la humanidad y que define como los asentamientos urbanos se han ido adaptando a sus condiciones climáticas. Este conocimiento, manifestado en la arquitectura vernácula se ha filtrado en ocasiones a prácticas arquitectónicas modernas o contemporáneas, evolucionado hacia nuevas técnicas o sistemas constructivos

***

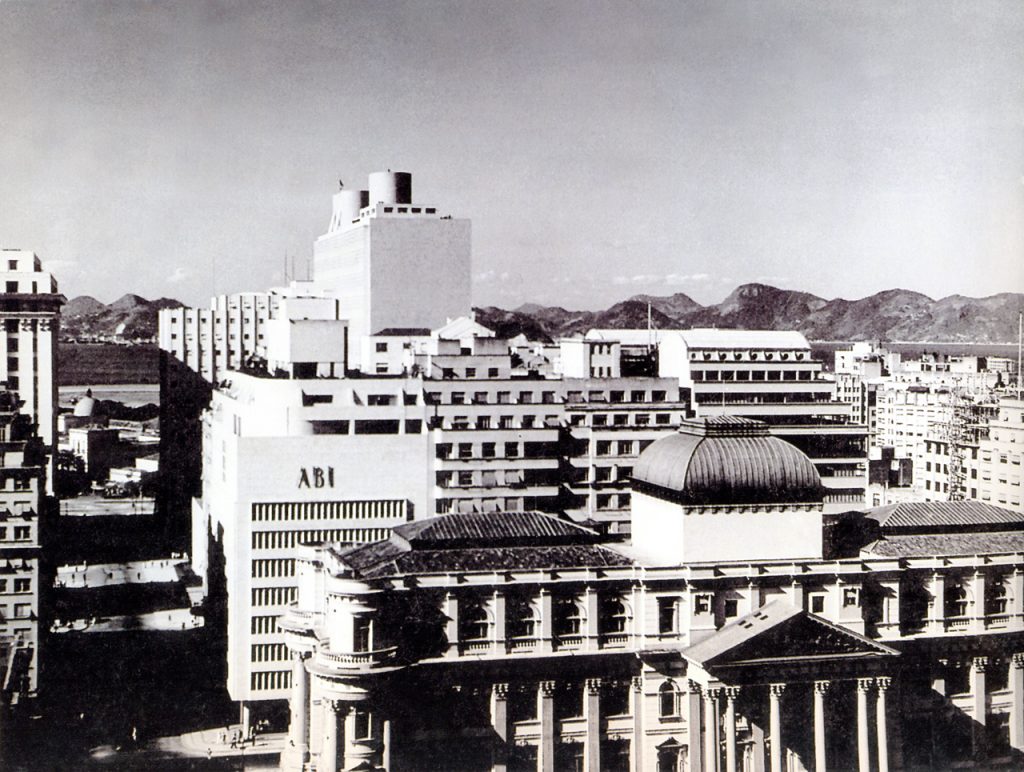

Example: Sede Associação Brasileira de Imprensa (ABI)

***

Brise-Soleil is any permanent solar obstruction system that blocks or deflects the solar rays. This system can be both static or movable, and it can be located both in a facade or a roof. To reduce all the possibilities and systems, in this article of the series UNGREEN, I am briefly starting with the evolution of the façade systems by Le Corbusier in Europe during the 1930s, and I am omitting those vernacular examples he could have used as a reference. Then, I am moving to Brazil to explain the expansion of the system, first with Le Corbusier himself in the Ministry of Education Building and, mainly, with the Headquarters of the Brazilian Journalist Association, designed by the Roberto Brothers, both in Rio de Janeiro.

Se denomina Brise-Soleil a cualquier sistema de protección solar permanente que obstaculice o desvíe los rayos solares. Este sistema puede estar colocado en una fachada o una cubierta y existen tanto sistemas estáticos como móviles. Para reducir el abanico de sistemas y posibilidades, dentro de este artículo de la serie UNGREEN, me centraré brevemente en la evolución del sistema de fachada por parte de Le Corbusier desde los años 30, obviando aquellos ejemplos de la arquitectura vernácula y popular que pudieran haber surgido anteriormente. Posteriormente me desplazaré a Brasil para tratar la expansión de este sistema, primero por parte del propio Le Corbusier en el edificio del Ministerio de Educación, y principalmente por los Irmaos Roberto en la Sede de la Asociación Brasileña de Prensa, ambos en Río de Janeiro.

The article ends with a brief thought regarding the method or the logic rules, unshakeable, of the solar control and the results the Brise-Soleil can contribute to the composition of the façade. Brazil and the Roberto Brothers were crucial for the development of the Brise-Soleil: First, Le Corbusier “invented this system shortly after traveling to Brazil in 1929. He developed it during the next years in Europe and Africa, but he finally built his first large project using this system in Rio de Janeiro. Moreover, unlike other countries where Le Corbusier used this system, in Brazil, the Brise-Soleil was developed by local architects at the same time. The overlap in developing it in both continents at the same time makes its origin untraceable. In Brazil, architects transformed the Brise-Soleil in a characteristic element of their projects with various variations. Finally, the Roberto Brothers used it in most of their project in a very useful form, as if they were reproducing a formula to provoke a precise result in their interiors and façade. Their projects became pedagogical to understand the passive solar protection system.

El articulo terminará con una breve reflexión acerca del método o las reglas lógicas, inquebrantables, del control solar que implica el brise-Soleil y los resultados compositivos que conllevan. La elección de Brasil como país de análisis y los Hermanos Roberto como arquitectos principales de este artículo no es casual. Le Corbusier desarrolló este sistema usando sistemas propios de la arquitectura brasileña como el cobogó tras visitar el país en 1929, lo desarrolló más adelante en varios proyectos en Europa y África para finalmente construir el primer gran edificio con este sistema de vuelta en Brasil. A diferencia de otros países donde Le Corbusier uso este sistema, en Brasil el brise-Soleil de desarrolló al mismo tiempo que en Europa siendo borroso el origen real del mismo. Además en Brasil, se convirtió en un elemento característico de la propia arquitectura brasileña con un gran abanico de distintas derivaciones. Los Hermanos Roberto, por su parte, utilizaron el brise soleil en muchos de sus edificios de un modo directo, como si aplicaran una fórmula en busca de un resultado específico de incidencia solar en los interiores de sus edificios. Esto permite que sus proyectos sean profundamente pedagógicos en cuanto a su sistema pasivo de protección solar.

MAIN FEATURES OF THE BRISE SOLEIL | PRINCIPALES CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL BRISE SOLEIL

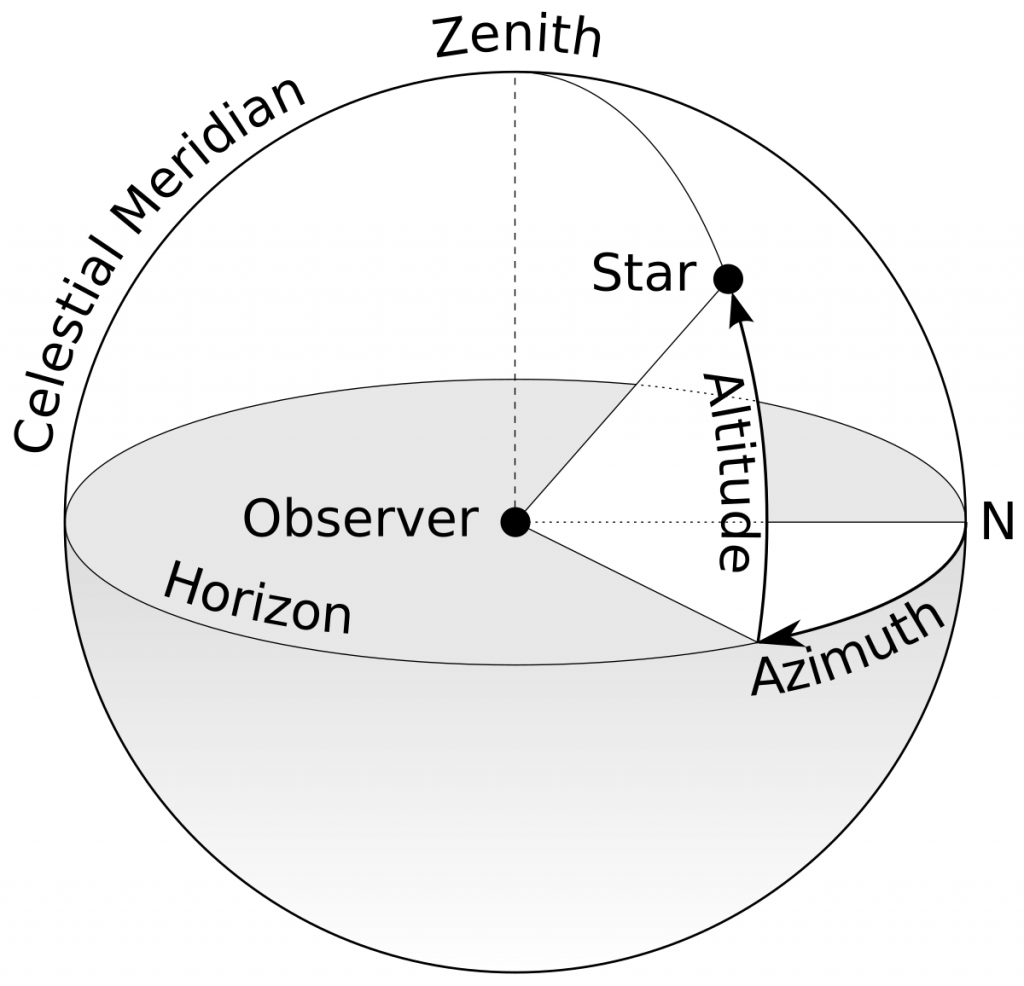

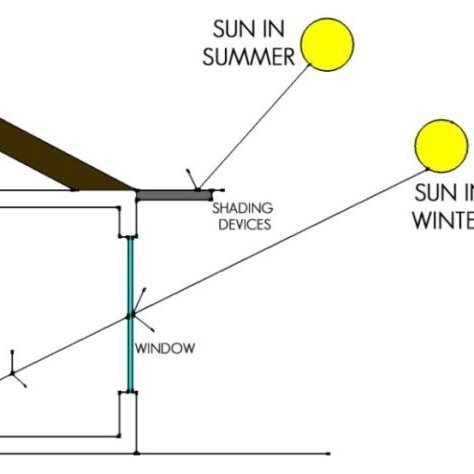

Before analyzing the features of the Brise-Soleil and its different types, it is necessary to briefly describe how to measure the solar radiation in a building. Sun charts depict the sun’s geometry and allow us to know its exact position at a particular latitude: this is the base to control human comfort regarding sun radiation. The sun chart’s two parameters are the azimuth (the sun’s trajectory) and altitude (angle of the sun regarding the ground). Through the sun charts, we can understand the sun’s orbit on any day of the year and time of the day and, therefore, its impact on a building’s openings. These sun charts are the base that allows us to decide where we want to block the sun. We can design a sunshade that blocks the light in summer but let go through the windows in winter (based on the sun’s altitude depending on the season). Moreover, we can design a sunshade that allows the blocks the sun only at certain times of the day.

Para entender el funcionamiento del Brise-Soleil así como sus distintas posibilidades, es preciso describir brevemente el Asoleamiento. Este concepto define el estudio de la incidencia solar en un ambiente interior con el fin de encontrar el confort higrotérmico de dicho espacio. El estudio se basa en la geometría solar – representada de manera precisa en las cartas solares. Estas nos permiten conocer la posición exacta del sol en unas coordenadas geográficas específicas y a una hora del día determinada a través de su azimut (trayectoria horizontal) y ángulo solar (trayectoria vertical). A través de las cartas solares podemos entender el recorrido del sol a lo largo de cualquier día del año y por tanto su incidencia sobre una apertura de un edificio. Estas cartas solares son las base que nos permite poder decidir en qué situación y momento queremos bloquear la entrada de luz mediante un sistema de Brise-Soleil o cualquier otro sistema de obstrucción solar. No solo podremos diseñar un parasol que permita la entrada directa de luz en invierno y la bloquee en verano (debido al ángulo solar en función de la estación del año) sino que también podremos protegernos del sol a ciertas horas del día y permitir su entrada a otras: el asoleamiento en una misma apertura puede tener una temporalidad anual pero también diaria.

ORIGINS OF BRISE SOLEIL: LE CORBUSIER | ORÍGENES DEL BRISE SOLEIL: LE CORBUSIER

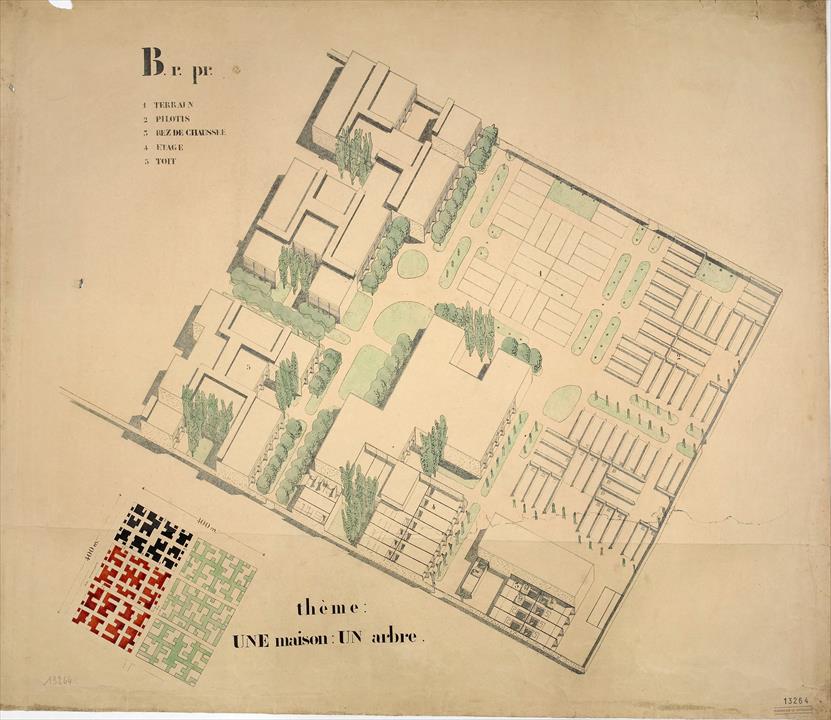

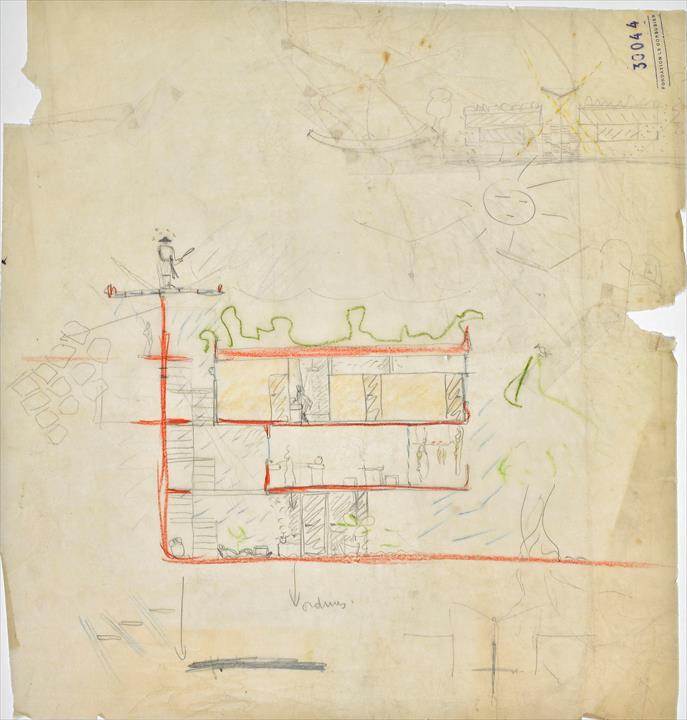

Several historians such as Daniel A. Barber (Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning) od Ignacio Requena (Arquitectura Adaptada al Clima en el Movimento Moderno: Le Corbusier (1930-1960), set the beginning of the Brise-Soleil, or at least the first documented project with this system, in 1929 with the Lotissement project by Le Corbusier. Located in Barcelona, these houses would have occupied a 400 x 400 meters site and would be internally organized by several smaller streets. Each house had a ground floor and two upper levels connected with a staircase in the building’s back. The staircase also worked as a skylight to bring sunlight to the back rooms. Each house’s façade has a large gate on the ground floor, a balcony on the second floor and a horizontal window on the third floor. The upper floors façade is covered with horizontal shades that can be movable and protect the interior from sun exposure: this is the first Brise-Soleil of the modern movement. It is possible that when Le Corbusier designed these houses, he was not aware yet of the possibilities of the Brise-Soleil and the necessity of design it and orient it concerning the site it was going to be built. In the Lotissement, the houses are oriented in all the cardinal points (north, south, east, and west), but the façade does not change. The Brise Soleil is horizontal and would only properly work when it faces south. Then, it does not work for most of the houses. Moreover, as Ignacio Requena explains in his thesis (Movimento Moderno: Le Corbusier (1930-1960), page 70), the Brise-Soleil was over-dimensioned to the solar radiation of Barcelona what it would have provoked a lack of natural light in the interior of the housing.

Varios historiadores como Daniel A. Barber (Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning) o Ignacio Requena (Arquitectura Adaptada al Clima en el Movimento Moderno: Le Corbusier (1930-1960) , sitúan el origen del Brise Soleil, o al menos el primer proyecto documentado con este sistema, en el proyecto de viviendas Lotissement (alojamientos para obreros) de Barcelona, proyectado por Le Corbusier en 1931. Estas viviendas se proyectaron para un solar de 400 x 400 metros que a su vez se dividía internamente por varias calles de menor tamaño. Cada vivienda tenía una planta baja y dos superiores que se conectaban mediante una escalera situada en la parte trasera. Esta escalera también actuaba como un patio de luces para las habitaciones posteriores. La fachada de la vivienda se compone de una gran compuerta en planta baja, un balcón en planta primera y una ventana corrida en planta segunda. Los dos pisos superiores se cubren con unos listones horizontales que protegen el espacio interior de los rayos solares: el primer Brise Soleil del movimiento moderno. Es posible que cuando Le Corbusier proyectó estas viviendas no fuera del todo consciente de la capacidad del Brise Soleil y la necesidad de diseñarlo y orientarlo en función de la incidencia del sol en el lugar donde iba a ser construido. En el proyecto de Barcelona, las viviendas se orientan en todas direcciones (norte, sur, este y oeste) pero la fachada es siempre la misma. El Brise Soleil, al ser horizontal, solo funciona adecuadamente cuando está orientado hacia el sur, por tanto en Lotissement es inservible en casi todas sus disposiciones. Además, como explica Ignacio Requena en su tesis doctoral (Movimento Moderno: Le Corbusier (1930-1960), página 70), el Brise Soleil estaba sobredimensionado para la incidencia solar de Barcelona lo cual habría impedido una correcta iluminación natural interior.

Le Corbusier’s project proposed a new language for its facade from the ornamental and functional perspectives, even with its insecurities. It would have control the amount of natural light received from the exterior without compromising the windows’ size. Then, views and sunlight would not have to be related, and both parameters could be maximized simultaneously. Moreover, the composition of the façade would not depend on the location of the windows; the Brise-Soleil would become another element to work with, becoming the façade a neutral part or breaking it down in different scales. Within the Le Corbusier work, he used the Brise-Soleil for a neutral façade in the Carpenter Center in Boston or the Maison Locative, an unbuilt project in Argel. The Shadows tower in Chandigarh could be an example of breaking down a façade with the Brise-Soleil.

El proyecto de Le Corbusier, de forma aún tímida, proponía un nuevo lenguaje de fachada tanto utilitario como ornamental. Por un lado, permitía regular la cantidad de iluminación que se recibía del exterior sin comprometer el tamaño de las aperturas de la fachada. De este modo visibilidad e incidencia solar no tenían que estar vinculadas entre sí y podían maximizarse ambos parámetros al mismo tiempo. Además, la composición de la fachada ya no tenía que depender de la disposición de las ventanas si no que su estructura podía unificarse con el Brise Soleil como elemento neutro. Por otro lado, la fachada puede descomponerse en distintas escalas, siendo en este el Brise Soleil un elemento de menor tamaño. Un ejemplo del primer caso en la obra de Le Corbusier sería el Centro Carpenter en Boston, o la Maison Locative, proyecto sin construir en Argelia. Para el caso de aproximación ornamental al Brise Soleil sería el ejemplo del Ministerio de Educación en Río de Janeiro, del que hablaremos posteriormente o la Torre de Sombras en Chandigarh.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE BRISE SOLEIL TO BRASIL AND THE ROBERTO BROTHERS | LA LLEGADA DEL BRISE SOLEIL A BRASIL Y LOS HERMANOS ROBERTO

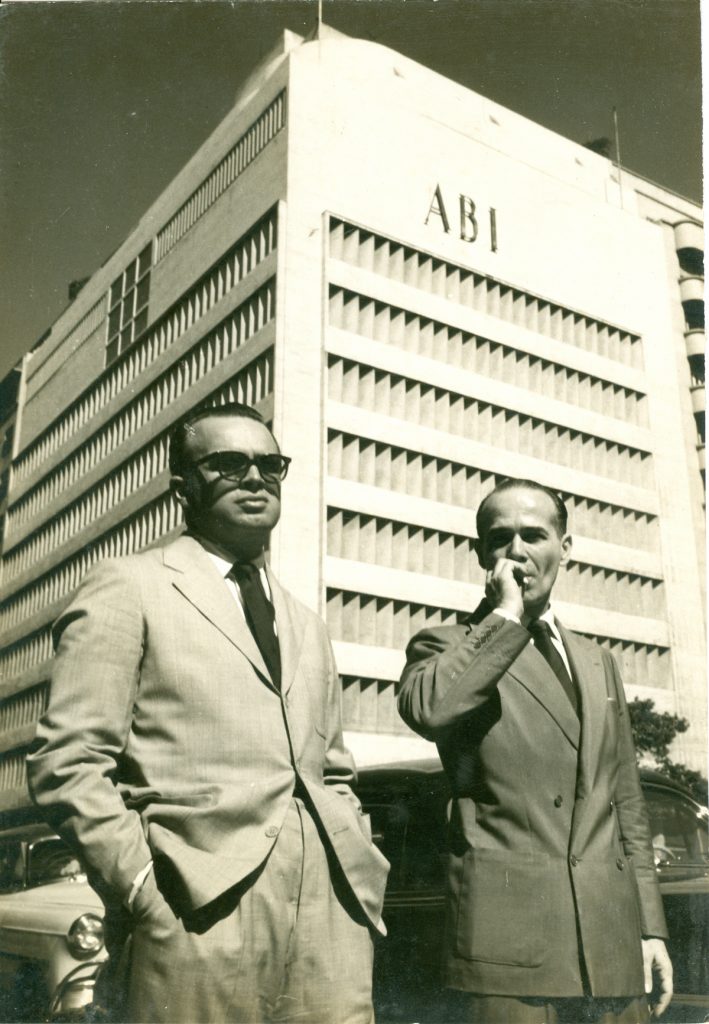

Brazil twice in that period. First, he went in 1929 as part of a trip that included Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Later, in 1936, he was invited by the Minister of Education, Guastavo Capanema, to give a series of 6 lectures and work in the minister’s new building. At the same time, in 1936, The Brazilian Press Association (Associação Brasileira de Imprensa in Portuguese) organized a competition in Rio de Janeiro to design his new headquarters. Two young brothers: Marcelo and Milton Roberto, won it, proposing a building with a system of vertical louvers that would completely cover its openings. As Luiz Felipe Machado Coelho de Souza states in his Book Irmaos Roberto, Arquitectos (page 165), the architects claimed that this building was the first system Brise-Soleil. It is impossible to know if Marcelo Roberto knew Le Corbusier’s initial projects or attended Le Corbusier’s lectures in Brazil or when he traveled to Europe in 1929. Nonetheless, beyond the original authorship of the Brise-Soleil system, it is interesting to see Brazil’s radical evolution with this system.

El desarrollo del Brise-soleil durante los años 30 ocurrió de manera paralela en Brasil y Europa, siendo difuso la principal autoría de su transformación. Le Corbusier viajó a Brasil en dos ocasiones, primero en 1929 como parte de un viaje por Latinoamérica que incluiría Buenos Aires y Montevideo, y más adelante en 1936, invitado por el ministro de educación Guastavo Capanema para realizar un ciclo de seis conferencias y trabajar en el edificio del ministerio. Paralelamente, ese mismo año se organiza el concurso para el nueva Sede de la Associação Brasileira de Imprensa (ABI) en Río de Janeiro que ganarían dos jóvenes hermanos arquitectos: Marcelo y Milton Roberto, proponiendo un volumen con un sistema de lamas verticales que lo cubría por completo. Como documenta Luiz Felipe Machado Coelho de Souza en su libro Irmaos Roberto, Arquitectos (pag. 165), los autores sostendrían que era el primer edificio que incorporaba un quebra-sol (sistema de parasoles). Es difícil saber si Marcelo Roberto conoció los proyectos iniciales de Le Corbusier con Brise-Soleil en alguna de las conferencias que Le Corbusier realizó en Brasil, o en el viaje que éste realizó a Europa durante 1929. Más allá de la autoría original del Brise-Soleil, es interesante ver la evolución radical que tuvo este sistema en Brasil.

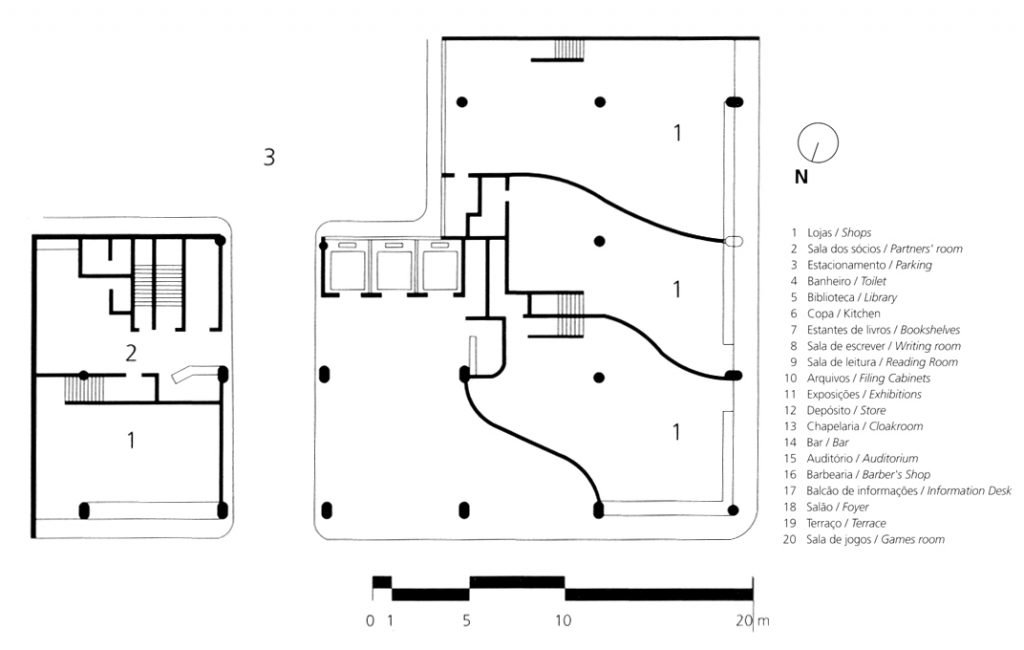

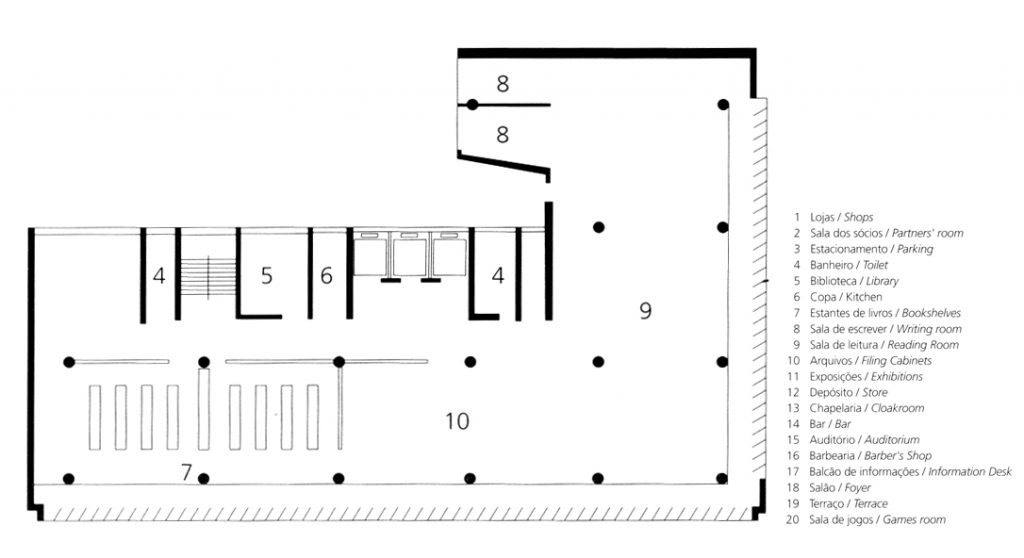

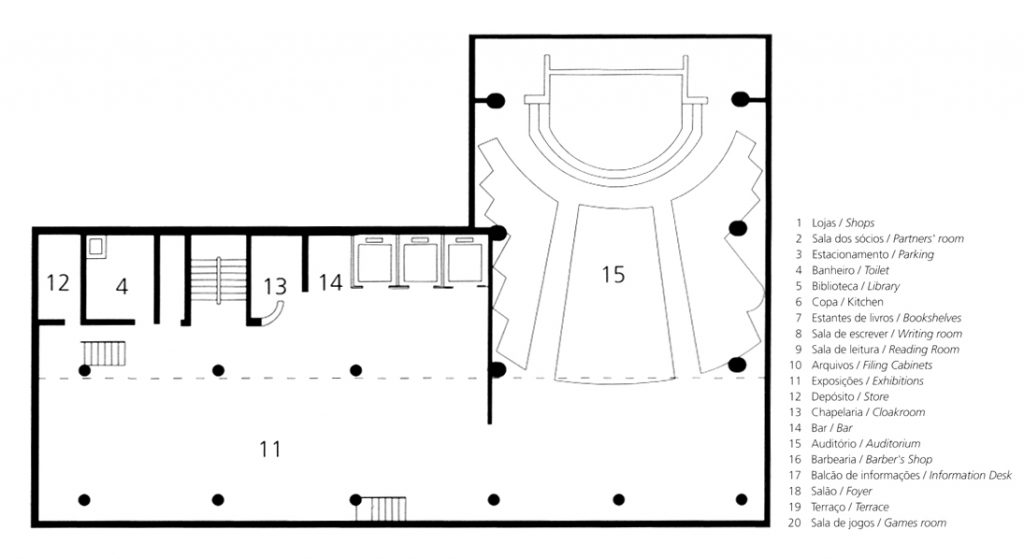

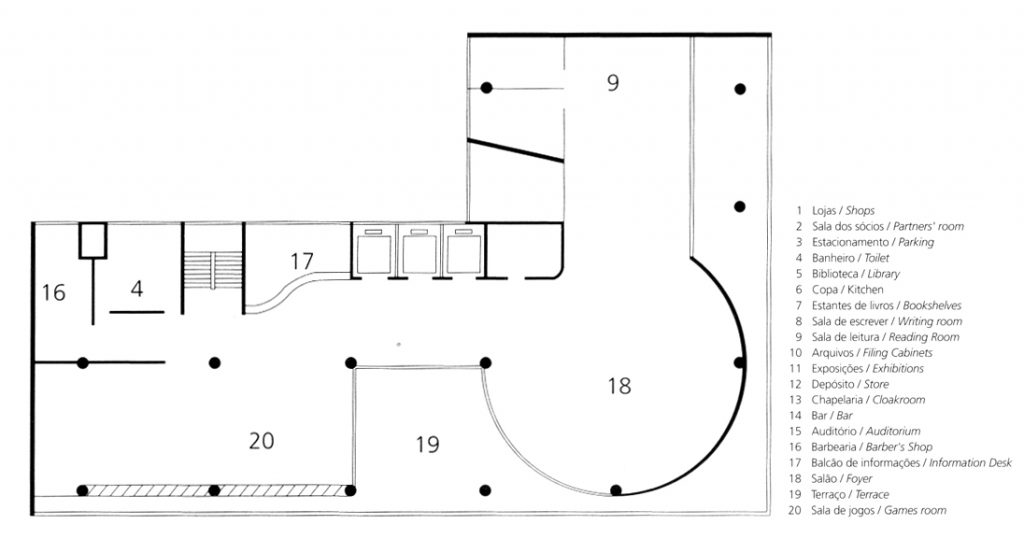

Drawings of the Associação Brasileira de Imprensa (ABI)

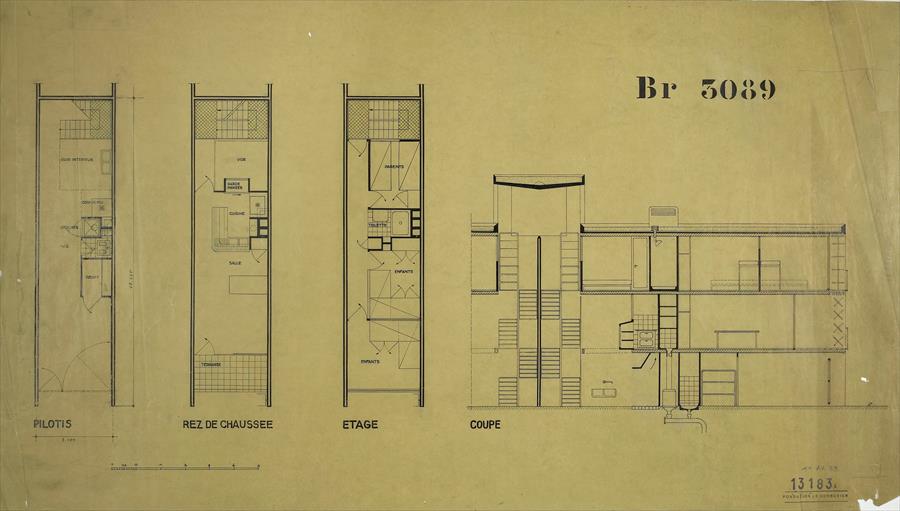

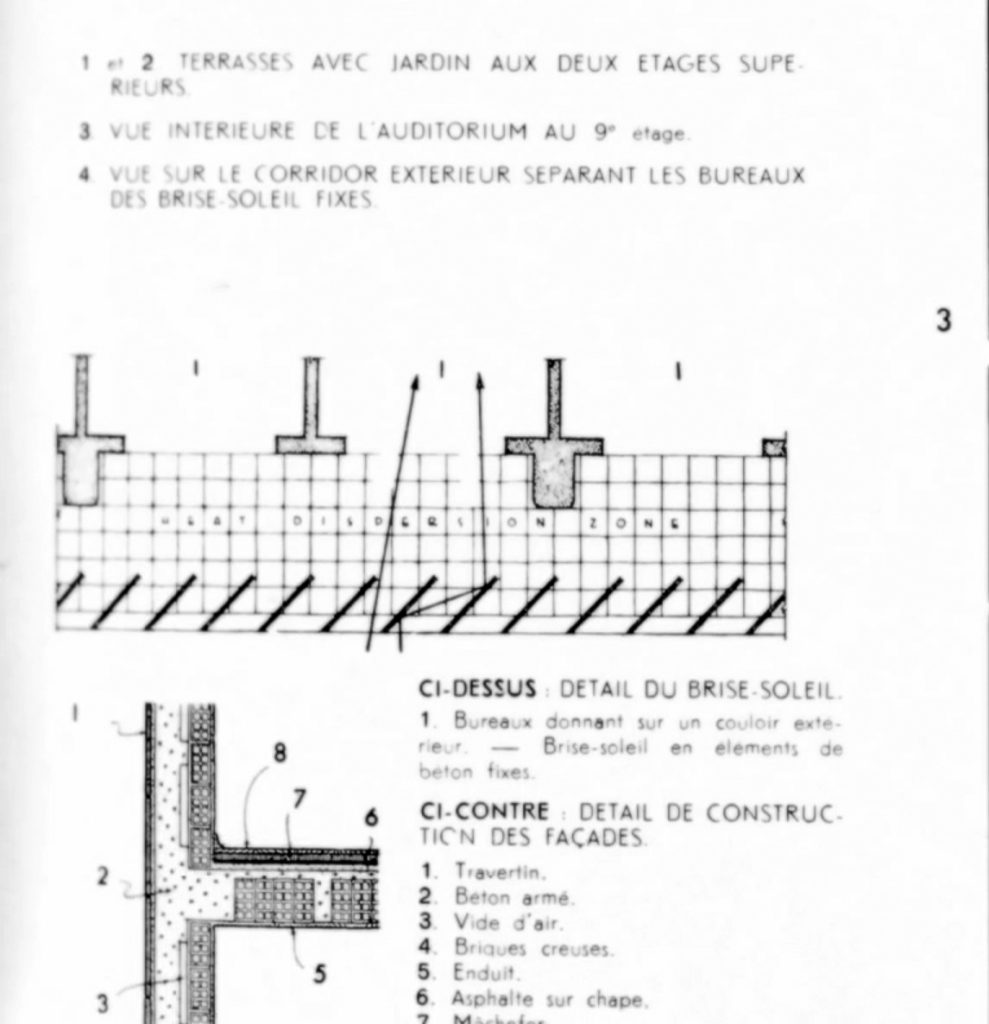

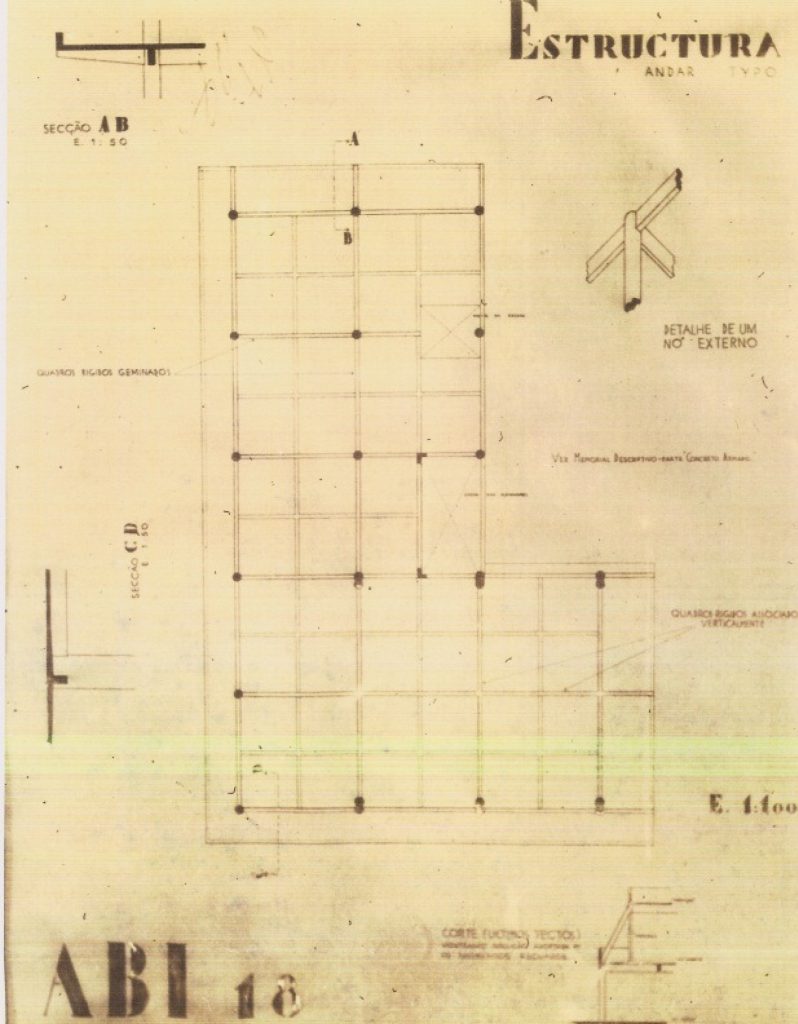

The new headquarters of the Brazilian Press Association, near the Santos Dumont Airport, is located in a corner site with north and west orientation. The Roberto Brothers Project followed the five points of modern architecture, published by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in 1927: The building is supported by Pilotis, partially opening the ground floor to the street; the free plan is repeated in all the levels, allowing to modify the layouts on each floor; the roof plan has a garden with tropical plants; the façade is offset from the structure, and the horizontal windows can run freely through the entire façade. Nonetheless, these windows from the second to the eighth floor are protected with a vertical Brise-Soleil.

La nueva Sede de la Associação Brasileira de Imprensa (ABI), localizada a escasos metros del Aeropuerto Santos Dumont, se encuentra en un solar en esquina con orientación Norte y oeste. El proyecto de los Irmaos Roberto seguía a la perfección los cinco puntos de la arquitectura moderna, publicados por Le Corbusier y Pierre Jeanneret en 1927: el edificio se apoya sobre pilotis, abriendo parcialmente la planta baja a la calle; la planta libre se repite en todos sus niveles, modificando la organización interna en cada piso; la cubierta se ajardina con plantas tropicales brasileñas; la fachada se separa de la estructura permitiendo que su composición no sea dependiente de su sistema; y se crean ventanas horizontales que atraviesan toda la fachada a lo largo de toda su longitud. Sin embargo estas ventanas, desde la planta segunda hasta la octava se protegen con un sistema de Brise-Soleils verticales.

The heaviness of the facade was controversial, but, at the same time, it was positive to win the competition. The president of the Brazilian Press Association thought that its modern character would reinforce the image of the Association (Irmaos Roberto, Arquitectos; page 165). From the climatic perspective, Roberto’s Brothers also had a lack of awareness about the Brise-Soleil since they used the same system for the north and west facades.

La rotundidad de la fachada fue controvertida debido a su masividad formal pero, al mismo tiempo, decantó el resultado del concurso a su favor, ya que el presidente de la ABI pensó que la rotundidad del edificio reforzaría la imagen de la Asociación (Irmaos Roberto, Arquitectos; pag. 165). Desde el punto de vista climático, los Irmaos Roberto también mostraron cierto desconocimiento del funcionamiento del Brise-Soleil ya que usan el mismo sistema para las fachadas norte y oeste.

For the west facade, the system was conceptually well developed since the sun reached the building horizontally during the evening, and the vertical panels could protect the interior from it. Nonetheless, in the north façade (in the southern hemisphere, it receives the sun mainly in the afternoon), the vertical panels were not very useful or, at least, not with the same density as the west façade. In this case, a system of horizontal louvers would have protected the building more efficiently.

En la fachada oeste, el sistema funcionaba de forma precisa, ya que el sol alcanzaba la fachada del edificio horizontalmente al atardecer y los paneles verticales protegían el interior de los rayos directos del sol. Sin embargo, la fachada norte (en el hemisferio sur recibe un sol vertical al mediodía principalmente), los paneles verticales no eran de gran utilidad, o al menos, no con la misma densidad de ocupación que en la fachada oeste. En este caso, un sistema de lamas horizontales hubiera protegido de la incidencia solar con mayor efectividad.

Regarding this aspect, the Ministry of Education, designed by a group of Brazilian architects led by Lucio Costa and consulted by Le Corbusier, developed a more rational and sensitive local weather Brise-Soleil. This building, located one block away from the ABI Building, had a glass façade on the south façade and a mixed Brise-Soleil (vertical and horizontal) on the north side that protected the building from afternoon and evening sun.

En ese sentido, el Ministerio de la Educación, proyectado por un grupo de arquitectos brasileños que lideraba Lucio Costa y asesorados por Le Corbusier, desarrolló el Brise-soleil de forma más sensible al clima local. Este edificio estaba situado en el bloque anexo a la Sede de la Associação Brasileira de Imprensa . Mientras que su fachada sur estaba totalmente acristalada, la fachada norte tenía un Brise-Soleil mixto (horizontal y vertical) que resguardaba el interior tanto de los rayos del mediodía como del atardecer.

In Roberto’s Brothers building, it is essential to mention the space created between the interior glass facade and the Brise-Soleil. This threshold between the exterior and interior, usually forgotten when this project has been described, is probably one of the richest areas besides the terrace. It has the proportions of a corridor and an undefined function, but I can connect the entire floor plan through its perimeter without any obstruction. As we can see in the documentary Os Irmãos Roberto, the space was occupied by planting, creating an informal garden.

Regresando al edificio de los Hermanos Roberto, es necesario referirse a espacio que se creaba entre el Brise-Soleil y la fachada interior de vidrio. Este umbral entre el interior y el exterior, normalmente olvidado cuando se describe este proyecto, es quizás uno de los mayores logros espaciales de este edificio con su planta de terraza. Con proporciones de corredor y sin una función precisa, conecta toda la planta perimetralmente sin ningún tipo de obstrucción. Como se puede ver en el documental Os Irmãos Roberto, el espacio se ha ido ocupando con varias plantas creando un pequeño jardín informal.

After this project, Roberto’s Brothers, already including Mauricio, the youngest brother, built a series of remarkable buildings, where the Brise-Soleil was the central element of the façade. In the following projects, they better understood the system and were able to refine and innovate about it. Some of these projects were the IRB BUILDING (Insurance Headquarters of Brazil) in 1941, the Headquarters Building da Companhia Seguradoras in 1949, and the Marques do Herval Commercial Building in 1952. These projects will be published in Hidden Architecture in future publications as an annex of this Ungreen article.

Tras este proyecto, los Hermanos Roberto, ya incluyendo al hermano pequeño Mauricio como parte del equipo, realizaron una serie notable de edificios, donde el Brise-Soleil era un elemento central de la fachada. En sus sucesivos proyectos, los Hermanos Roberto comprendieron mejor el sistema y fueron capaces de perfeccionarlo e innovar al respecto. Entre estos se encuentra el IRB (Sede do Instituto de Resseguros do Brasil) en 1941, el Edificio-Sede Da Compahia Seguradoras en 1949, o el Edificio Comercial Marques do Herval en 1952. Estos proyectos se irán publicando en futuras publicaciones en Hidden Architecture, como anexos de este artículo de la serie Ungreen.

MONOTHONY vs DIVERSITY | MONOTONÍA vs DIVERSIDAD

The Brise-Soleil can work as a superficial element attached to a conventional façade or have enough depth to create an intermediate space between the exterior and interior. This spatial feature of the Brise-Soleil, beyond its bioclimatic performance to sun exposure, is possibly the most important from the architectural perspective.

El Brise-Soleil puede actuar como un elemento superficial superpuesto a una fachada convencional, o tener la suficiente profundidad para crear un espacio intermedio entre el exterior y el interior. Esta característica espacial del Brise-Soleil, más allá de su respuesta bioclimática a la incidencia solar, es quizás la más enriquecedora desde el punto de vista arquitectónico.

Moreover, the Brise-Soleil is a remarkable element to compose facades since it can create a significance of its exterior. It evokes a sensitive response to climate in a moment where sustainability is not only a technical problem but also a political statement. Under this premise, the Brise-Soleil can build a canonical façade, repeating an element on a rigid orthogonal grid. Nonetheless, it can also create infinite variations through duplicating a single element and only rotating or eliminating some them from a grid. This variation, if it is manipulated with precision in relation to sun can create a façade that reacts to the environment and, because of its depth, it can create a better connection between the interior and exterior.

Por otro lado, el Brise-Soleil es un elemento compositivo privilegiado para la configuración de las fachadas ya que permite dotar de significado el diseño exterior. Evoca un diseño sensible al clima en un momento en el que la sostenibilidad no es únicamente un problema técnico sino también un componente simbólico. Con esta premisa, el Brise-Soleil puede construir desde una fachada totalmente disciplinada repitiendo el elemento dentro de una malla ortogonal convencional, hasta producir una variación casi infinita mediante la clonación de un único elemento, únicamente rotándolo, o eliminando algunos de sus duplicados dentro de dicha malla. Esta variación, si es tratada de un modo quirúrgico, sin despreciar el soleamiento, pero incorporando otros parámetros tales como vistas, distintos grados de privacidad es capaz de generar una fachada que reacciona al entorno y paradójicamente, a través de su profundidad en sección, permite mantener una mejor conexión entre el interior y el exterior.

Bibliography:

– BARBER, Daniel A. Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning. Princeton University Press. 2020.

– MACHADO COELHO DE SOUZA, Luiz Felipe. Iramos Roberto, Arquitectos. Rio Books. 2014

– REQUENA RUIZ, Ignacio. Le Corbusier y el brise-soleil. Universidad de Alicante. 2009

– REQUENA RUIZ, Ignacio. Arquitectura adaptada al clima en el Movimiento moderno: Le Corbusier (1930-1960) . Universidad de Alicante. 2009