The commission: It was 1975, I had been forced to leave the cabinet of projects of the Home Trade Union, directed by the architect Antonio Vallejo. I had worked there, three years, very comfortable, with my colleagues, José Carlos Velasco and Alfonso Valdés, and with other architects, surveyors, engineers, draughtsmen and administrators. I had drafted a few projects of vocational schools and directed the works. And I finished with some experience and without work. In the mornings, I began to give technical drawing classes at ETSAM. In the afternoons, I had free time. The architect María Luisa López Sardá (henceforth, Pispa), recently married to my friend José Carlos, had an assignment from ICONA and suggested that we solve it halfway. His father, Filiberto López Cadenas, forest engineer, introduced us to his colleague Antonia Aldama, chief engineer of the Cercedilla mountains. They wanted to make an installation that would attract the hikers, so that they would meet in a place, instead of dispersing through the rest of the forest. They said that, thus, it would be easier to control the behavior of those who damaged the forest or the negligence of those who could cause the feared fires. They proposed building a swimming pool, changing rooms, a first-aid kit, a picnic area and a store selling firewood for barbecues. We visited the place where they wanted to install the “recreational services”: a wonderful forest of wild pines, on the southern slope of the Sierra de Guadarrama, above Cercedilla. We went to see what constructions ICONA did in its domains. They were modest and conventional masonry constructions that lined with trunk walls to acquire a rustic look, Davy Crockett-like. We decided that, to do that, they did not need us, and that we had to propose something else.

El encargo: Era el año 1975, me había visto obligado a abandonar el gabinete de proyectos de la Obra Sindical del Hogar, que dirigía el arquitecto Antonio Vallejo. Yo había trabajado allí, tres años, muy a gusto, con mis compañeros de carrera, José Carlos Velasco y Alfonso Valdés, y con otros arquitectos, aparejadores, ingenieros, delineantes y administrativos. Había redactado unos cuantos proyectos de escuelas de formación profesional y dirigido las obras. Y me quedé con cierta experiencia y sin trabajo. Por las mañanas, empecé a dar clases de dibujo técnico en la ETSAM. Por las tardes, tenía tiempo libre. La arquitecta María Luisa López Sardá (en adelante, Pispa), recién casada con mi amigo José Carlos, tenía un encargo del ICONA y me propuso que lo resolviéramos a medias. Su padre, Filiberto López Cadenas, ingeniero de montes, nos presentó a su colega Antonia Aldama, ingeniero jefe de los montes de Cercedilla. Querían hacer una instalación que atrajera a los excursionistas, para que se reunieran en un lugar, en vez de dispersarse por el monte público. Decían que, así, sería más fácil controlar el comportamiento de los que deterioraran el bosque o las negligencias de los que pudieran provocar los temidos incendios. Proponían construir una piscina, unos vestuarios, un botiquín, un merendero y un almacén de venta de leña para las barbacoas. Visitamos el lugar en el que querían instalar los “servicios recreativos”: un bosque maravilloso de pinos silvestres, en la ladera meridional de la sierra de Guadarrama, encima de Cercedilla. Fuimos a ver que construcciones hacía el ICONA en sus dominios. Eran construcciones de albañilería modesta y convencional que revestían con costeros de tronco para que adquirieran un aspecto rústico, a lo Davy Crockett. Decidimos que, para hacer aquello, no nos necesitaban, y que teníamos que proponerles otra cosa.

|

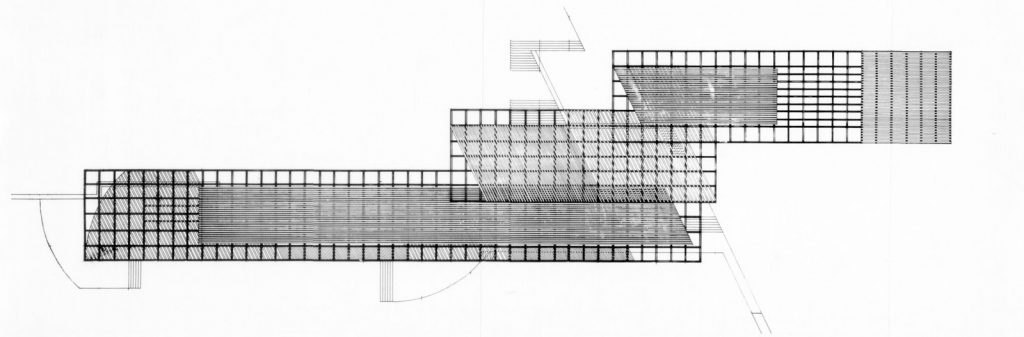

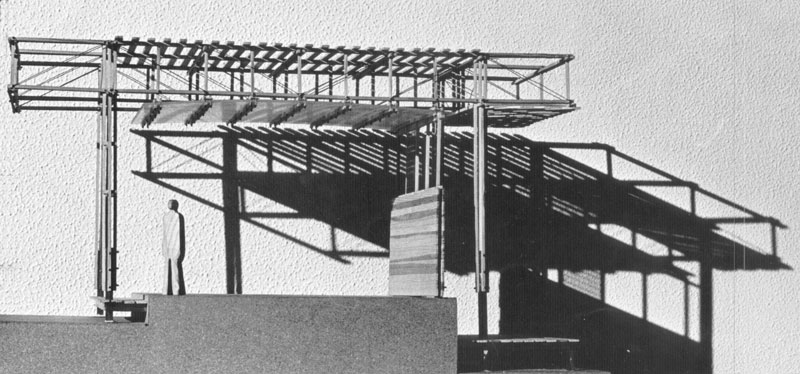

| Structural studies |

|

| Roofing Plan |

|

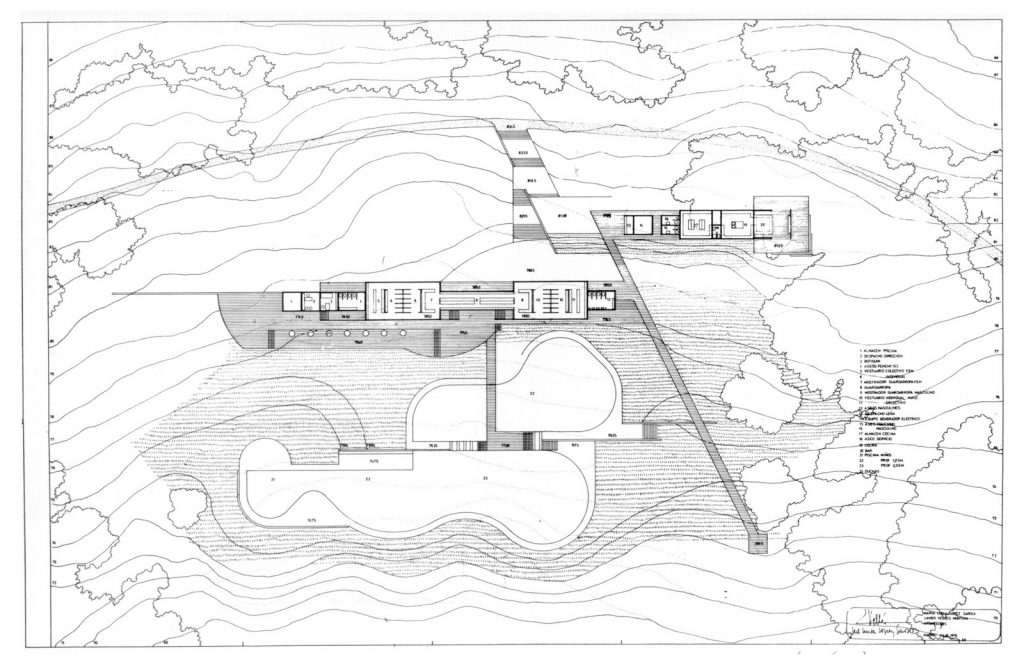

| General Plan |

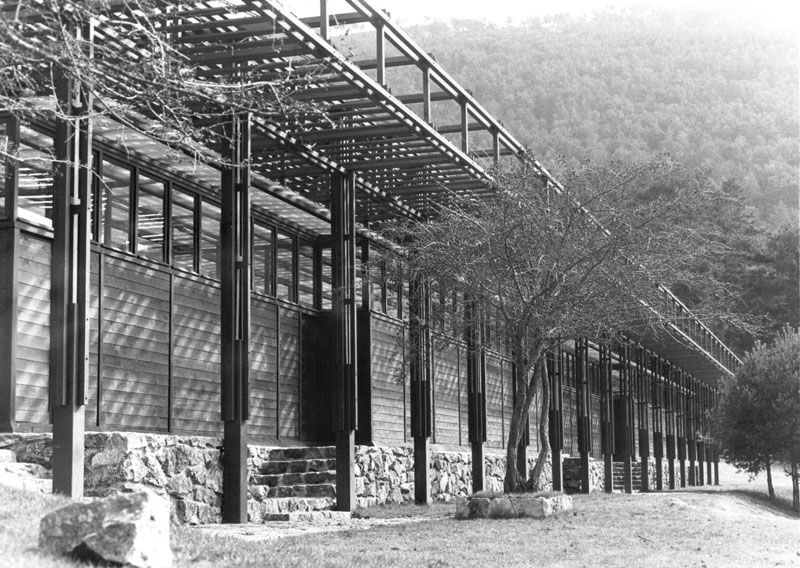

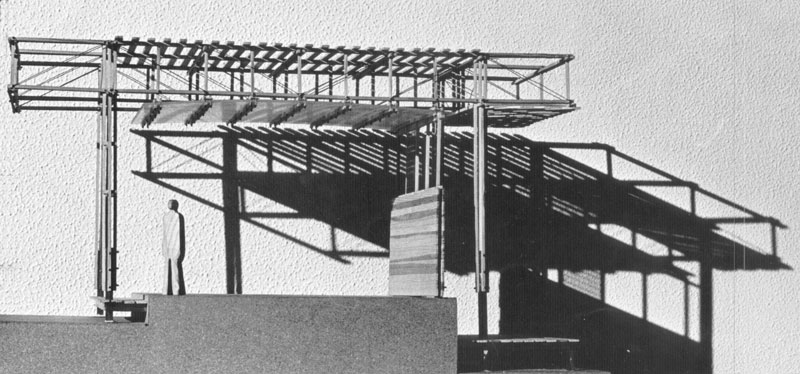

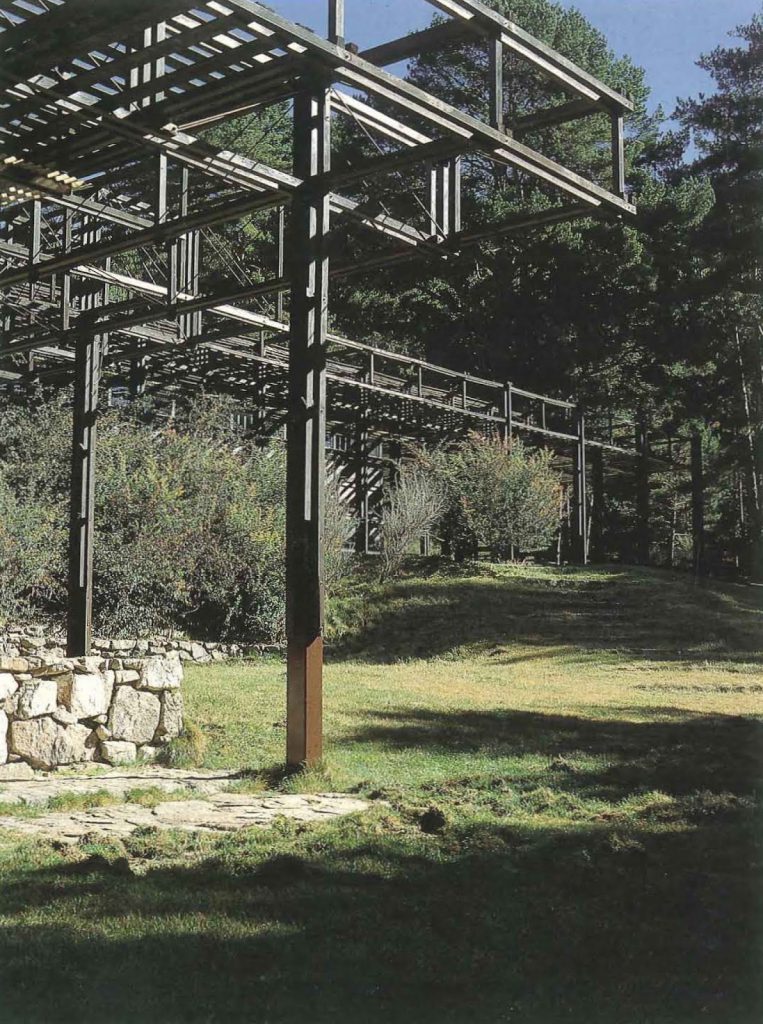

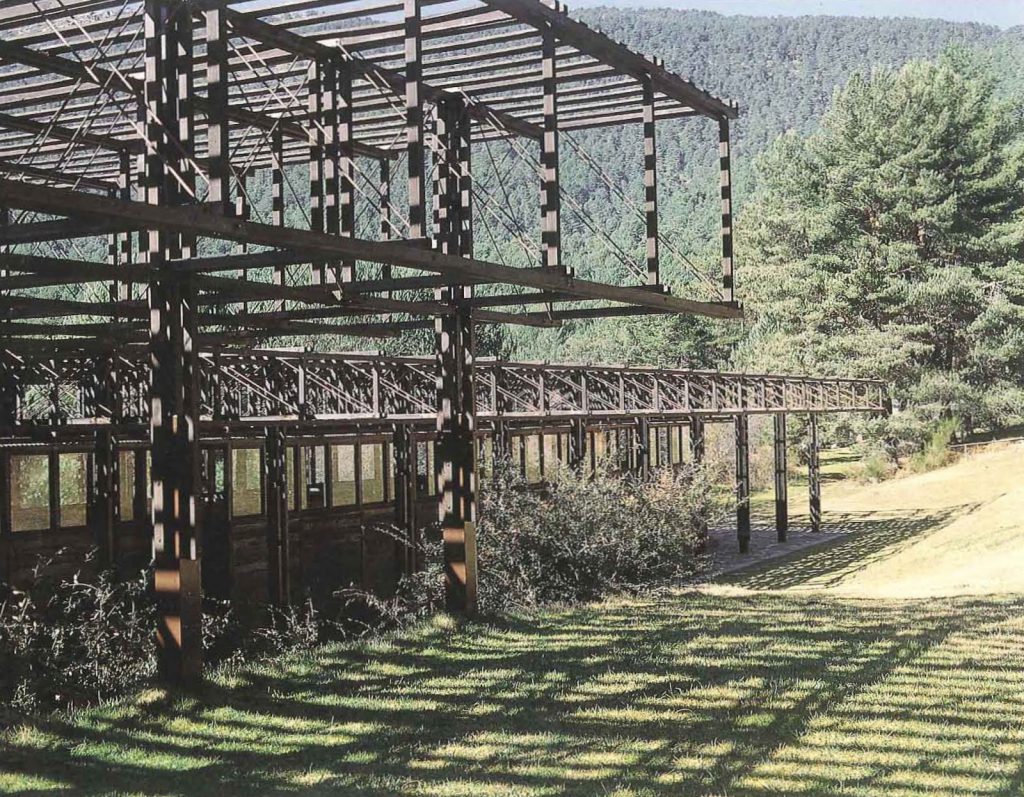

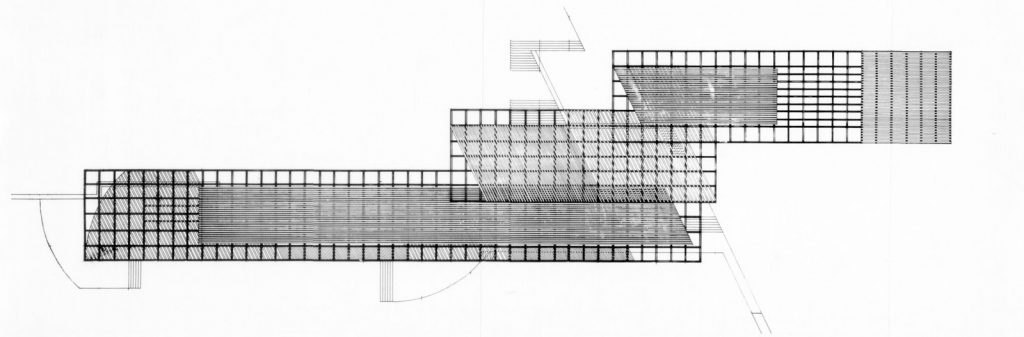

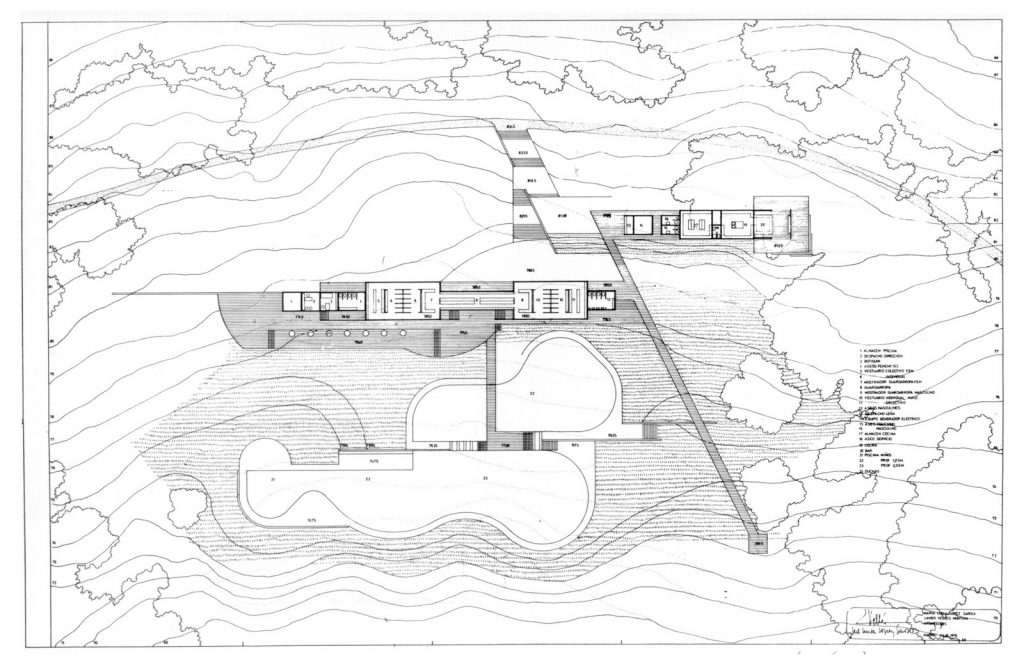

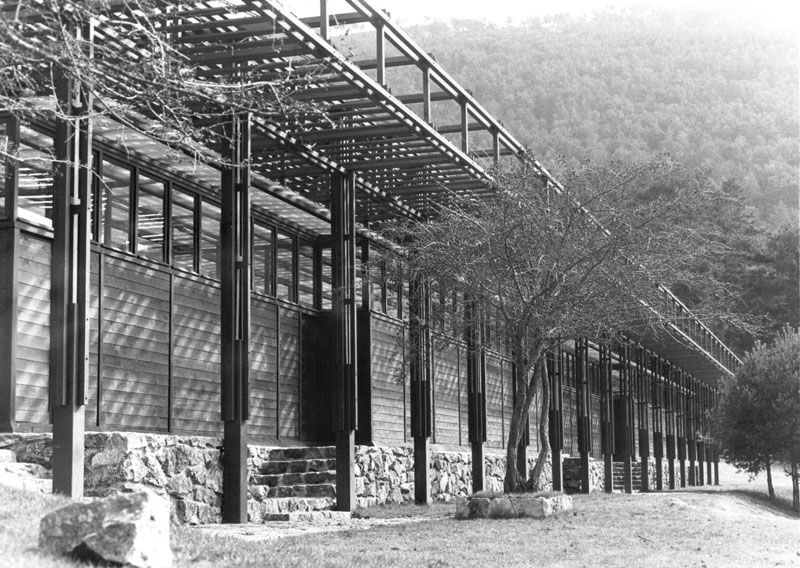

The project: We thought that some pavilions could be made, totally made of wood, whose construction was easy. We developed it quickly, drawing pencil sketches and precise plans with rotring. I remember the sources of inspiration: the umbráculo of the Ciudadela Park (Josep Fontseré, 1883), in Barcelona; the armchair Black, red and blue (Thomas Rietvel, 1917) and the picture Guitar and Pipe (polka) (George Braque, 1921-22). Knowing the planned site, we thought that, to carry out the whole, the largest clearing in the forest would be occupied by the pools, which need a clear space free of pine needles. We assumed that, in order to build the pavilions, a few pines would have to be cut down. We wanted the number of trees slaughtered to be the least possible and that the wood that was removed would be used for construction. On an excursion from the ETSAM, we had enjoyed visiting the umbráculo of Barcelona, a charming place, with its fine combs of sun and shade that reminded us of the interspersed light of the pine forests. Evoking that, we wanted to make a systematic framework of slats and boards that, protecting the pavilions, would return the stolen shade. This would allow the premises to have a translucent roof with the light-dark of the sifted rays, as in the forest.

El proyecto: Creíamos que se podrían hacer unos pabellones, totalmente de madera, cuya construcción fuera fácil. Lo ideamos rápidamente, dibujando croquis a lápiz y planos precisos a rotring. Recuerdo las fuentes de inspiración: el umbráculo del parque de la Ciudadela (Josep Fontseré, 1883), en Barcelona; la poltrona Negro, rojo y azul (Thomas Rietvel, 1917) y el cuadro Guitarra y pipa (polka) (George Braque, 1921-22).

Conocido el emplazamiento previsto, pensábamos que, para llevar a cabo el conjunto, el mayor claro del bosque lo ocuparían las piscinas, que necesitan un espacio despejado y libre de pinocha. Suponíamos que, para edificar los pabellones, habría que talar unos cuantos pinos. Pretendíamos que el número de árboles sacrificados fuera el menor posible y que la madera que se sacara sirviera para la construcción. En una excursión de la Escuela, habíamos disfrutado visitando el umbráculo de Barcelona, lugar encantador, con sus finos peines de sol y sombra que recordaban a la luz entreverada de los pinares. Evocando aquello, queríamos hacer un entramado sistemático de listones y tablas que, protegiendo los pabellones, devolviera la umbría robada. Esto permitiría que los locales tuvieran un techo traslúcido con el claro-oscuro de los rayos tamizados, como en el bosque.

It was said that the construction would be carried out by the ICONA staff, with their foremen, and that Juan Vielva, the engineer in the area, would be the construction manager. Intelligent, hierarchical and well-organized people, but who were not expert carpenters. It was necessary, then, to project a simple construction system. It was the systematic repetition of a way of doing that would soon get the hang of it. We admired Rietvel’s famous armchair, Black, Red and Blue, made of strips and boards that, surprisingly, were joined joining the crosses, apparently, without any assembly. Our construction was going to be something like that, but without tricks. An odd bundle of square sticks would intersect with another even beam. More clubs in the long sections, and less in the short ones. In the center of the crosses: steel drills and pins with shields and nuts; and the knots would be firmly tied. All the poles would be of the same square: slats of 6 x 6 cm. The lengths, variable, by series. The slats would form orthogonal lattices along the length, height and width of the set. The diagonal tractions would be absorbed with bars, moderately thin, of solid steel, with the extremes swaged and perforated, held by the same pins. The total lattice, despite its lightness, would be braced in the three directions of space and, like the faint wings of an old biplane, could withstand strong gusts of wind without breaking. We made a calculation memory. Nicolás Cermeño, who was then an architecture student, helped us. We presented some very clear sheets that explained the considered solicitations and the theoretical behavior of the structure against the forces. The engineers did not trust. They assumed that such a light building could not withstand heavy loads of snow. They demanded that we build the model of a module, with its elements of wood and metal, perfectly to scale, to test it, loading up to breakage. Jose Carlos and I, we were fans of boat models and the test amused me. We use fine square slats and cedar splints (the strength of the cedar is somewhat less than that of the Scots pine), and brass wire (the resistance of brass is also lower than that of steel). In the presence of the engineers, we submitted the model to the proportional load that was required. It was necessary to verify that the building would bear the weight of a great snowfall. Nothing happened. We doubled the load, tripled it, and the collapse still did not occur. It seemed that, even if it were in Siberia, our construction would bear with the snow that fell on it. They were sorry to destroy the model and we did not reach the break. The trial was a success.

Se habló de que la construcción la realizarían los guardabosques de la plantilla del ICONA, con sus capataces, y que, Juan Vielva, el ingeniero de la zona, fuera el jefe de obra. Gentes inteligentes, jerarquizadas y bien organizadas, pero que no eran carpinteros expertos. Había, pues, que proyectar un sistema de construcción ordenado y sencillo. Convenía la repetición sistemática de una manera de hacer a la que pronto se cogiera el tranquillo. Admirábamos la célebre poltrona de Rietvel, Negro, rojo y azul, constituida por listoncillos y tableros que, sorprendentemente, se unían adosándose en los cruces, aparentemente, sin ningún ensamble. Nuestra construcción iba a ser algo así, pero sin trucos. Un haz impar de palos cuadrados se cruzaría con otro haz par. Más palos en los tramos largos, y menos en los cortos. En el centro de los cruces: taladros y pasadores de acero con escudos y tuercas; y los nudos quedaría firmemente atados. Todos los palos serían de la misma escuadría: listones de 6 x 6 cm. Las longitudes, variables, por series. Los listones formarían entramados ortogonales a lo largo, alto y ancho del conjunto. Las tracciones diagonales se absorberían con barras, moderadamente finas, de acero macizo, con los extremos espadados y perforados, sujetas por los mismos pasadores. El entramado total, a pesar de su ligereza, estaría arriostrado en las tres direcciones del espacio y, como las leves alas de un biplano antiguo, podría aguantar fuertes rachas de viento sin desbaratarse. Hicimos una memoria de cálculo. Nicolás Cermeño, que entonces era estudiante de arquitectura, nos ayudó. Presentamos unas láminas muy claritas que explicaban las solicitaciones consideradas y el teórico comportamiento de la estructura frente a las fuerzas. Los ingenieros no se fiaban. Suponían que un edificio tan liviano no podía resistir fuertes cargas de nieve. Nos exigieron que construyéramos la maqueta de un módulo, con sus elementos de madera y metal, perfectamente a escala, para ensayarlo, cargando hasta la rotura. Jose Carlos y yo, éramos aficionados a las maquetas de barcos y la prueba me divertía. Usamos finos listones cuadrados y tablillas de cedro (la resistencia del cedro es algo menor que la del pino silvestre), y alambre de latón (la resistencia del latón también es inferior que la del acero). En presencia de los ingenieros, sometimos la maqueta a la carga proporcional que se exigía. Había que comprobar que el edificio soportaría el peso de una gran nevada. No pasó nada. Duplicamos la carga, la triplicamos, y seguía sin producirse el colapso. Parecía que, aunque fuera en Siberia, nuestra construcción aguantaría la nieve que le cayera encima. Les dio pena destruir la maqueta y no llegamos a la rotura. El ensayo fue un éxito.

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

While I taught at ETSAM, Pispa had just translated into Spanish, for Gustavo Gili, a book that was in vogue: Arthur Dresler, Colin Rowe and Kenneth Frampton, Five Architects. Eisenman Graves Gwathmey Hejduk Meier, New York Oxford University Press, 1972. In that book, we saw that the American neomodernist architects gave an artistic value to the planes that we found very attractive. And that the supposed beauty of their paths was related to Neoplasticism and Cubism. Incited by Oíza, I had bought, in an antique shop in Pollensa, a wonderful lithograph of Braque’s guitar and pipe (polka), which was almost the same size as the original. We pinned on that reproduction on the studio wall. And, while we painted the plant of the set, if we raised our heads, the image was present. And the relationship between the forms of the split pool and that of a decomposed guitar in the manner of Picasso, Braque or Gris, was conscious.

Mientras yo daba clase en la Escuela, Pispa acababa de traducir al español, para Gustavo Gili, un libro que estaba de moda: Arthur Dresler, Colin Rowe y Kenneth Frampton, Five Architects. Eisenman Graves Gwathmey Hejduk Meier, New York Oxford University Press, 1972. En aquel libro, veíamos que los neomodernos estadounidenses daban un valor artístico a los planos que nos resultaba muy atractivo. Y que la supuesta belleza de sus trazados estaba emparentada con el neoplasticismo y con el cubismo.

Incitado por Oíza, yo había comprado, en un anticuario de Pollensa, una estupenda litografía del cuadro Guitarra y pipa (polka) de Braque, que casi era del mismo tamaño que el original. Pinchamos aquella reproducción en la pared del estudio. Y, mientras pergeñábamos la planta del conjunto, si levantábamos la cabeza, la imagen estaba presente. Y la relación entre las formas de la piscina partida y la de una guitarra descompuesta a la manera de Picasso, Braque o Gris, fue consciente.

Text by Javier Vellés

VIA:

|

| Image by Estudio Javier Vellés |

|

| Image by Alfonso Quiroga |

|

| Image by Jesus Gallo |

|

| Image by Jesus Gallo |

|

| Image by Jesus Gallo |

|

| Image by Jesus Gallo |