***

Title: Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present

Editors: Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, Mabel O. Wilson

Editorial: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN: 9780822966593

Language: English

438 pages

***

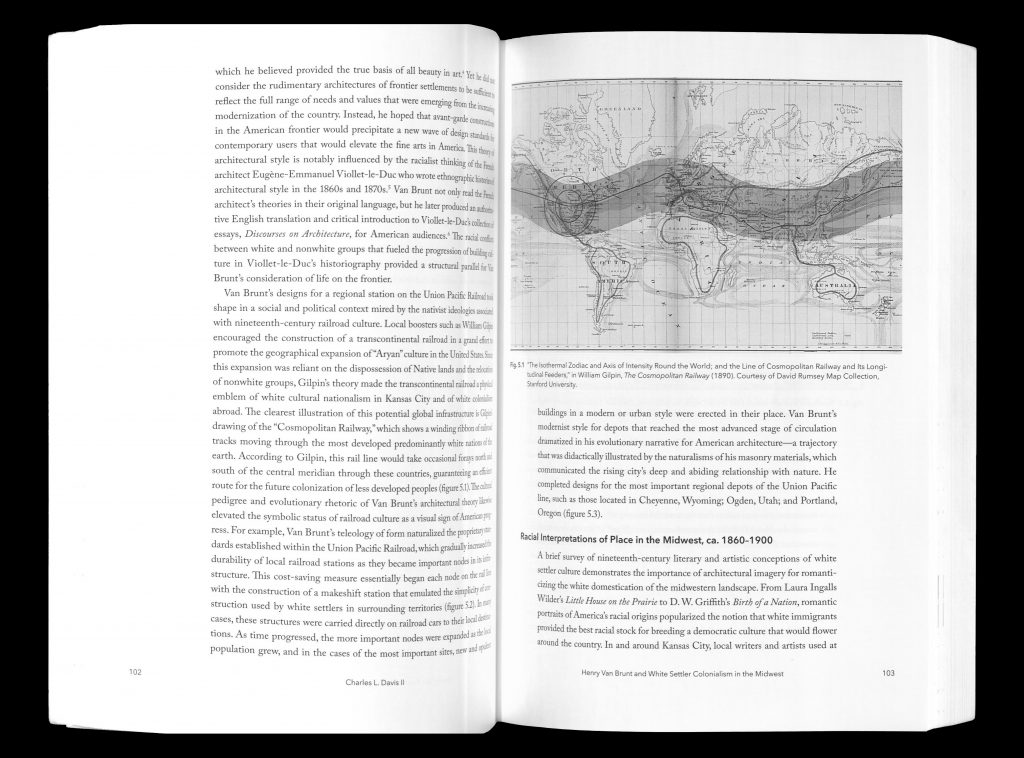

Until recently, modern architectural history, at least in the global north, has been only studied in one direction. We learned it was a glorious period, full of optimism, that took an entire civilization into progress. Nowadays, this position has started to fall apart with the various global crises occurring simultaneously, and different voices have begun to question that unidirectional approach towards architectural modernity. One of the topics previously avoided to discuss was the importance of racial theories in the development of the Modern Movement, particularly in the enlightenment period. Architectural theory has usually been more conservative than other historical areas, and these topics have been avoided for a long time. Although it is still a struggling topic, particularly among older generations, the book Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson, starts to unfold the importance of modern architectural history to create a racial division between Europe and the rest of the world. This division aimed to develop a superiority of European cultural above others. The book disassembles the idealized perception of progress during the Enlightenment and modern movement based on its racial biases, prejudices, and injustices.

Hasta hace relativamente poco tiempo, la historia de la arquitectura moderna, al menos en occidente, ha sido estudiada de forma unidireccional: fuimos enseñados que éste fue un periodo glorioso, optimista, que llevó a toda la civilización hacia un progreso sin fisuras. Esta posición ha comenzado a erosionarse recientemente causado por las distintas y simultáneas crisis globales. Desde distintos enfoques se comienza a cuestionar esta aproximación gloriosa sobre la modernidad. Uno de los temas del que se ha evitado hablar durante bastante tiempo han sido las teorías raciales que, por otro lado, fueron parte inherente del movimiento moderno y, sobre todo, de la Ilustración. La historia de la arquitectura ha tenido, por lo general, una posición más conservadora que otras áreas de estudio, y estos temas se han ido evitando. Aunque todavía es conflictivo, particularmente en círculos académicos más conservadores, el libro Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present (Raza y Arquitectura Moderna: Una Visión Crítica desde la Ilustración hasta la Actualidad en español), editado por Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II y Mabel O. Wilson, comienza a arrojar luz sobre estas ideas. El libro destaca la importancia en la historia de la arquitectura moderna para construir una división racial entre Europa y el resto del mundo. Esta división tenía como objetivo cimentar la superioridad cultural del continente sobre otras regiones. Race and Modern Architecture desmonta la idealización que se había previamente construido sobre la Ilustración y el movimiento moderno.

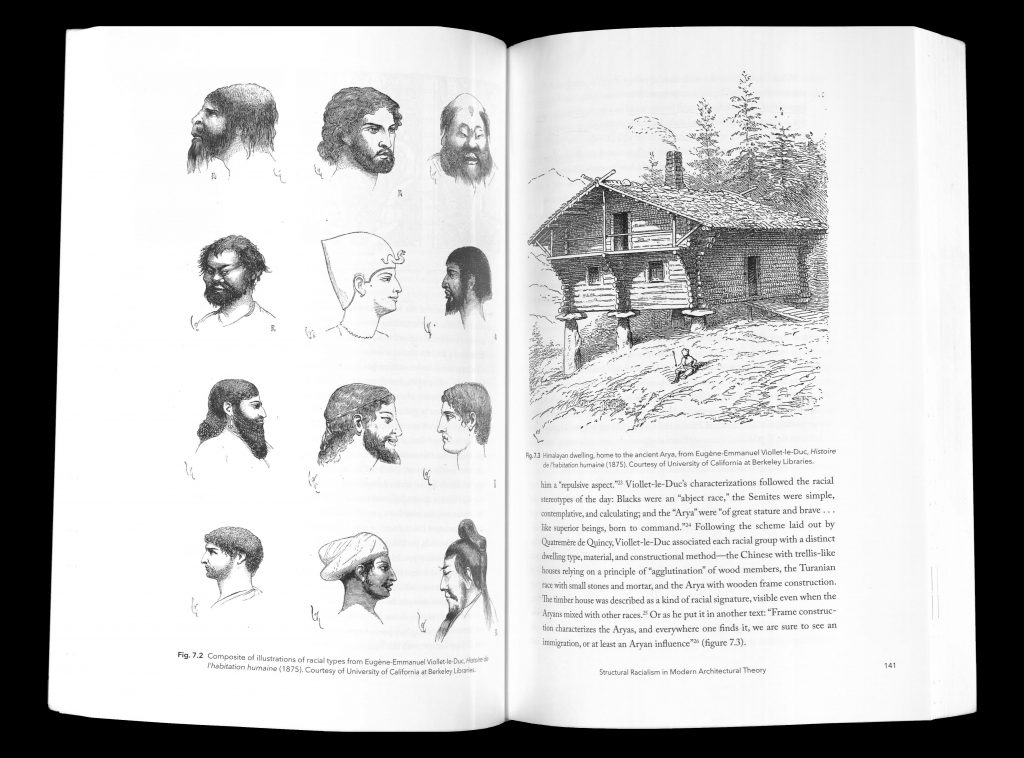

[Viollet-le-Duc] posited that a white race created the monuments of Uxmal, Tulum, and Chichén Itzá – or possibly a mixture of white and yellow – migrating across the Bering Strait; he was convinced that the present inhabitants of South America could not be responsible for such monumental constructions.

[Viollet-le-Duc] postuló que fue la raza blanca quien construyó los monumentos de Uxmal, Tulum y Chichén Itzá – o tal vez una mezcla de blancos y asiáticos – que habían migrado desde el estrecho de Bering. Él estaba convencido de que los actuales habitantes de América del Sur no haber sido capaces de llevar a cabo estas monumentales construcciones.

Irene Cheng, “Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory,” in Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, 144.

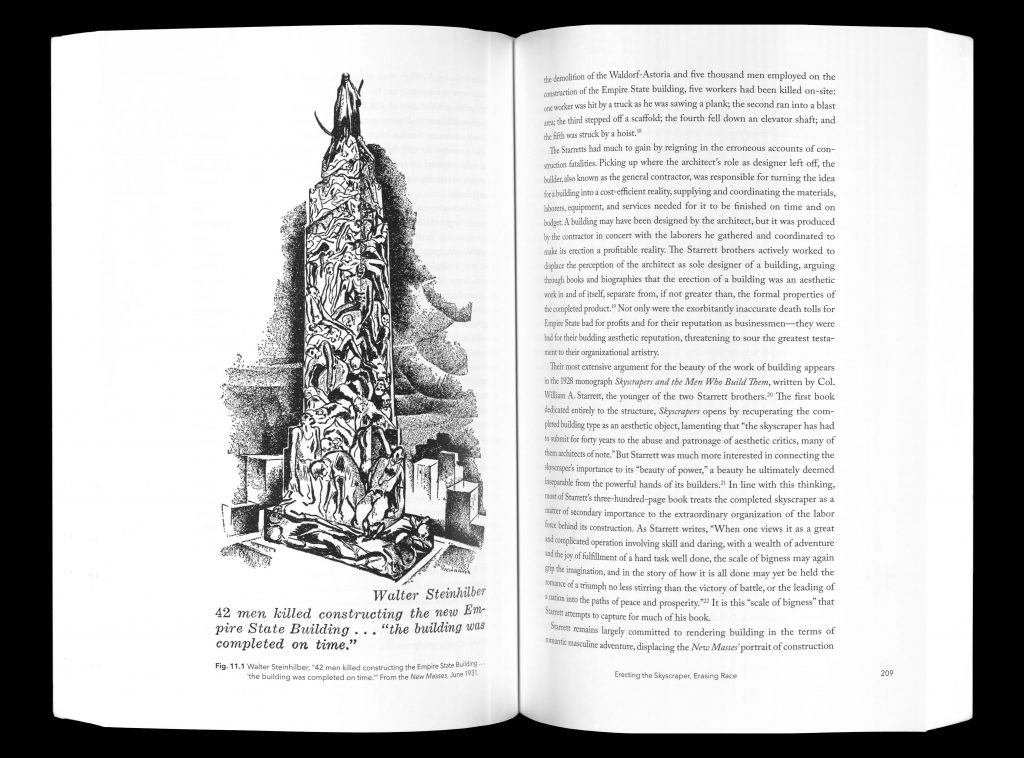

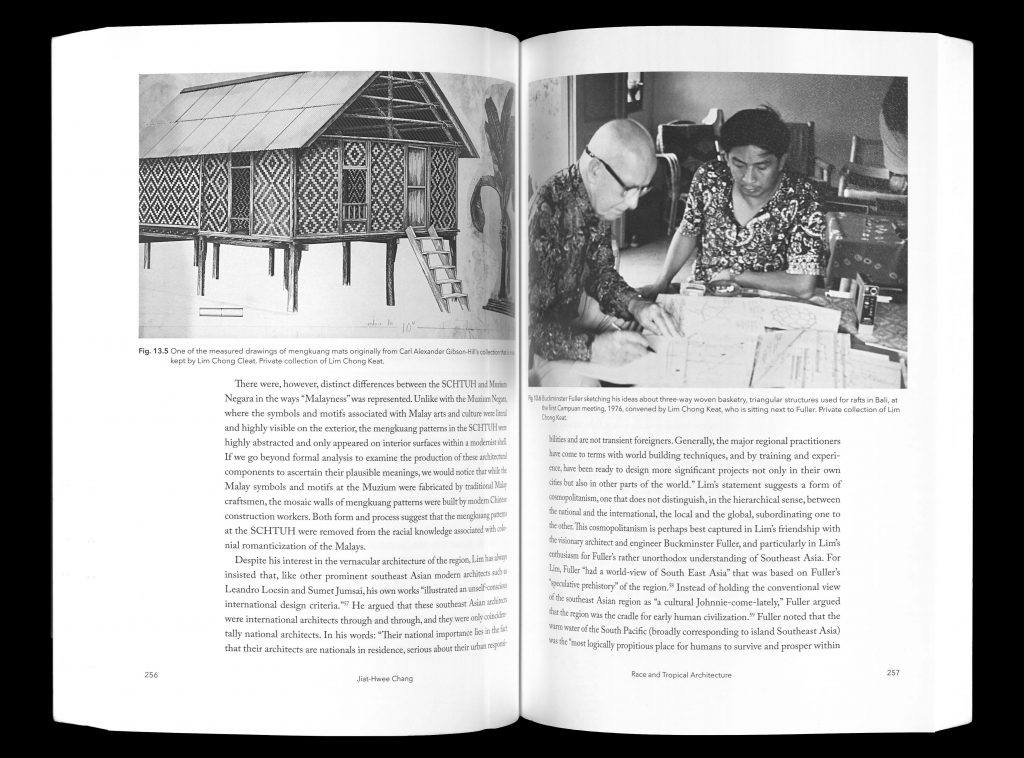

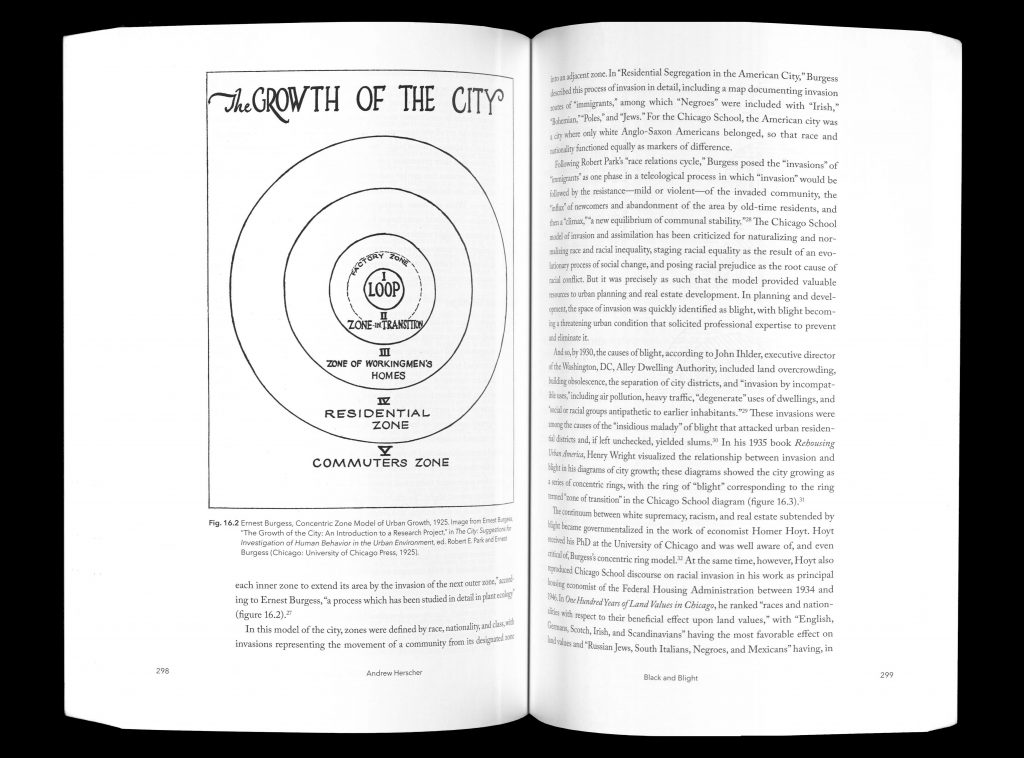

The book is divided into eighteen chapters organized into six sections, such as Race and the Enlightenment, Race and Nationalism, and Race and Representation. These chapters address different perspectives. Some focus on the official historiography of modernity, while others concentrate on how similar ideas were extrapolated to other contexts, particularly those regions currently defined as the global south. Within the first type of chapters, the text Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory by Irene Cheng stands out because she describes a critical perspective in the work of significant figures such as Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Owen Jones, and Adolf Loos. Cheng explains how these architects created a differentiation between races to construct the superiority of European civilization. Other chapters like Race and Miscegenation in Early Twentieth-Century Mexican Architecture, by Luis E. Carranza, and Race and Tropical Architecture, by Jiat-Hwee Chang, depict how this racialization worked during the 20th century in non-European countries. Carranza’s text is particularly appealing since he describes how contemporary questions, such as how to deal with colonial architecture, were previously addressed in Mexico.

El libro se divide en dieciocho capítulos organizados en seis secciones, tales como Race and the Enlightenment (Raza e Ilustración), Race and Nationalism (Raza y Nacionalismo), and Race and Representation (Raza y Representación) que enfocan la construcción de la raza desde distintos puntos de vista. Mientras que algunos se centran en la historiografía oficial de la modernidad, otros analizan la extrapolación de estas ideas en contextos periféricos, particularmente aquellas regiones denominadas hoy en día como el sur global. Dentro de los capítulos que tratan el tema de la raza desde su propia construcción occidental, es especialmente revelador el texto texto Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory (Racialismo Estructural en la Teoría Arquitectónica Moderna) de Irene Cheng. La autora deconstruye de forma crítica el trabajo de figuras clave de este periodo como Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Owen Jones y Adolf Loos. Cheng describe como estos arquitectos construyeron esta diferenciación racial para avalar la superioridad de la civilización europea. Además, en los textos Race and Miscegenation in Early Twentieth-Century Mexican Architecture (Raza y Mestizaje en la Arquitectura Mexicana de Principios del Siglo XX) de Luis E. Carranza, y Race and Tropical Architecture (Raza y Arquitectura Tropical) se describe como operó esta racialización durante el siglo XX fuera de entornos occidentales. El texto de Carranza es particularmente atractivo ya que explica como un tema tan actual como el posicionamiento de la arquitectura colonial en Latinoamérica fue previamente ya tratado en México, a principios del siglo pasado.

Young scholars, particularly in American universities, are currently working on similar themes, attempting to de-Westernize and decolonize academia. The topic of race needs to be explored more and still offers many angles to explore once studying architectural modernity from a canonical perspective seems obsolete. Thus, the book Race and Modern Architecture becomes a key referent of its content and the different methodologies of its authors. As the editors mention in its introduction, the book calls for further research to write race back into architectural history.

Arquitectos más jóvenes, particularmente en universidades estadounidenses, están estudiando la relación entre raza y arquitectura al tiempo que tratan de descolonizar y desoccidentalizar el mundo académico. Este tema tiene aún muchos aspectos por explorar ya que los análisis más canónicos en el mundo académico están quedándose obsoletos. Es aquí donde el libro Race and Modern Architecture puede convertirse en un referente dentro de este nuevo campo de investigación, tanto por su contenido como por las metodologías usadas por los autores en los distintos artículos. Como mencionan los editores en la introducción, el libro busca que se siga investigando y escribiendo sobre el tema de la raza dentro de la historia de la arquitectura.

Architects are still worried thinking about critical theory. One of the reasons may be the fear of considering that the foundation of their thinking is already incorrect. In our opinion, the topic is crucial to make the necessary questions, acknowledge the position of privilege created by some discourses, and construct new frameworks to include different approaches. The idea is not to erase the 200 years of architectural theory but deconstructs the single narrative of this period. And the book Race and Modern Architecture is an important keystone in this new path.

Aunque también es cierto que muchos arquitectos aún siguen preocupados sobre cómo afrontar este tipo de pensamiento crítico. Una de las razones a dicho miedo puede ser considerar que las bases que fundaron sus conocimientos ya no sirven. Sin embargo, en nuestra opinión, y a riesgo de poder equivocarnos o andar a tientas, creemos que es un tema crucial. Debemos hacernos las preguntas necesarias y conocer la posición de privilegio en la que nos movemos. Construir nuevos marcos de referencia e incluir otros enfoques es clave a la hora de seguir avanzando. No creemos que se trate de borrar 200 años de historia y teoría en la arquitectura, sino deconstruir la narrativa única, con la cual hemos sido enseñados. El libro Race and Modern Architecture es un paso necesario en este camino de deconstrucción.