Everyday is Like Sunday

Todos los dias son como si fuera domingo

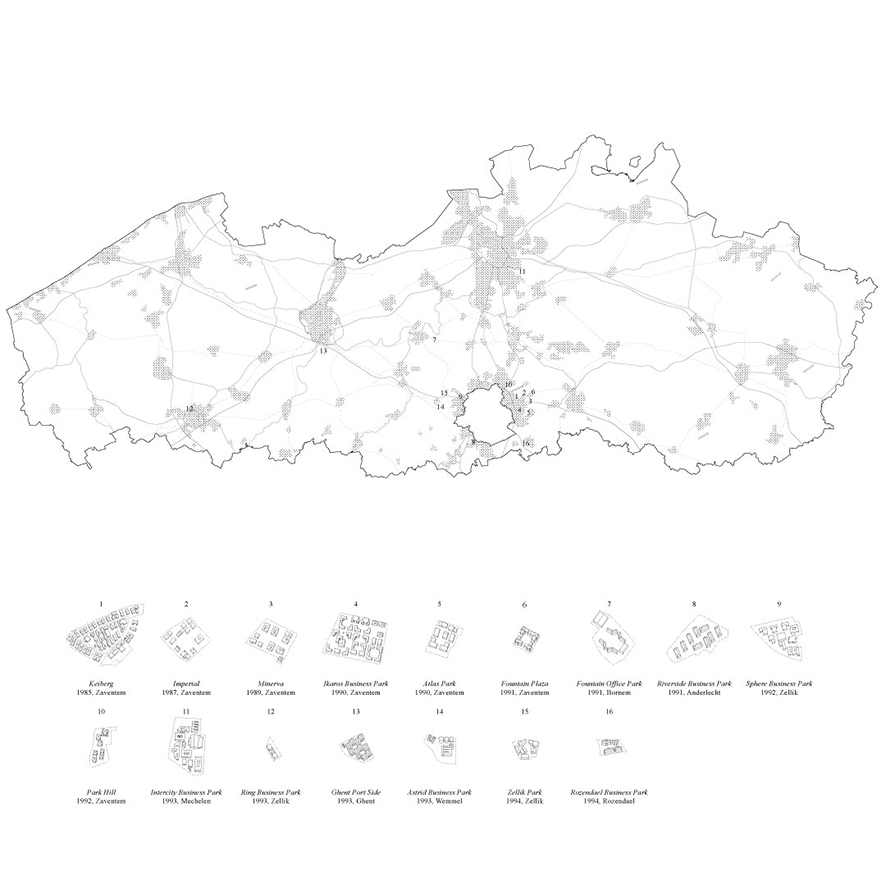

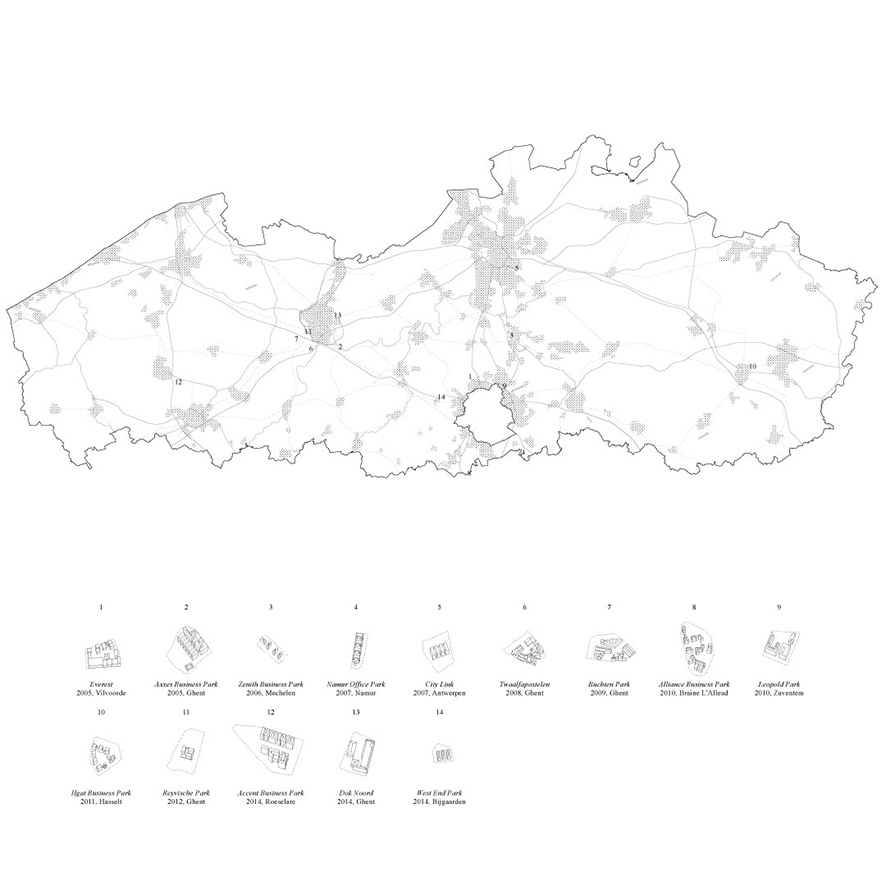

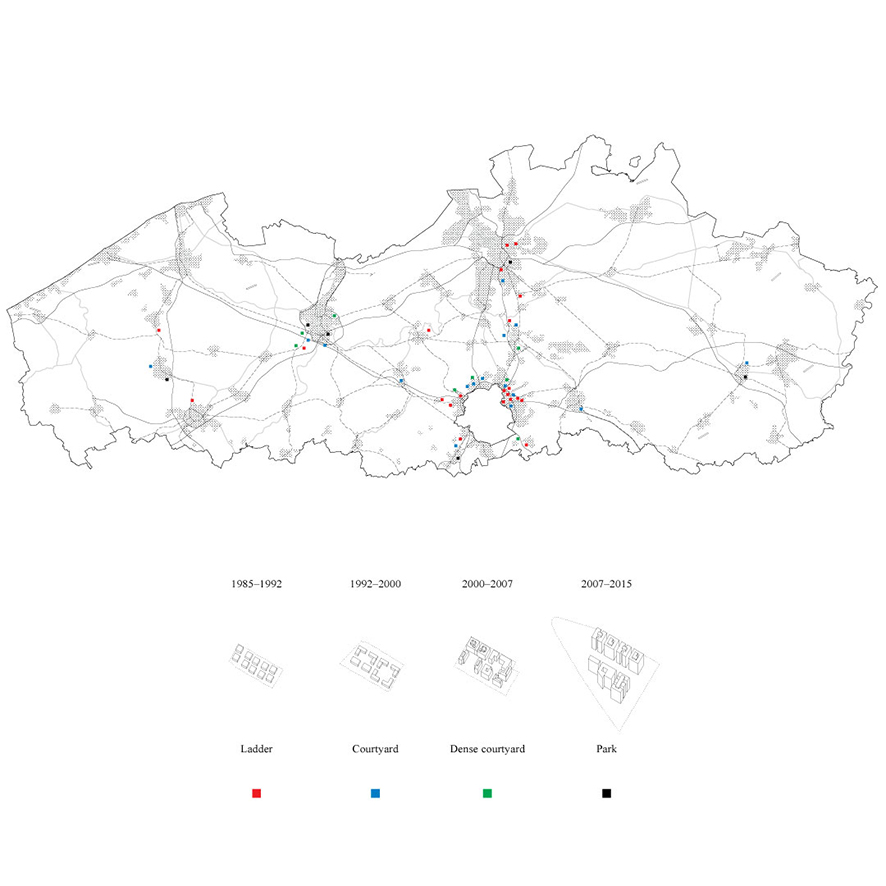

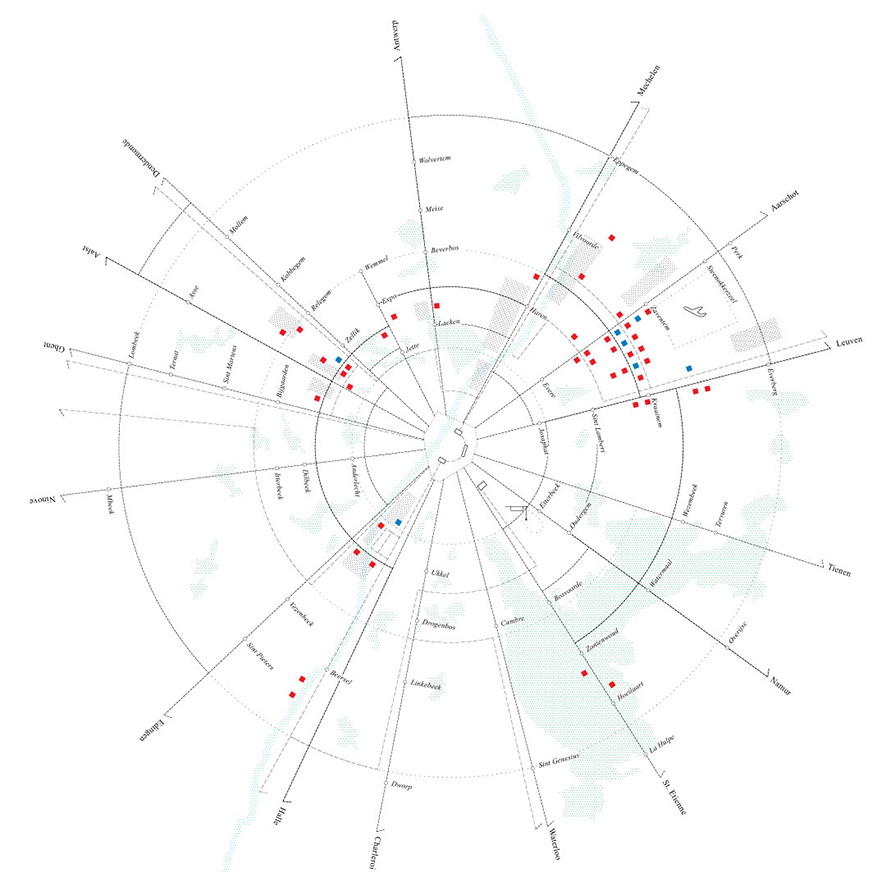

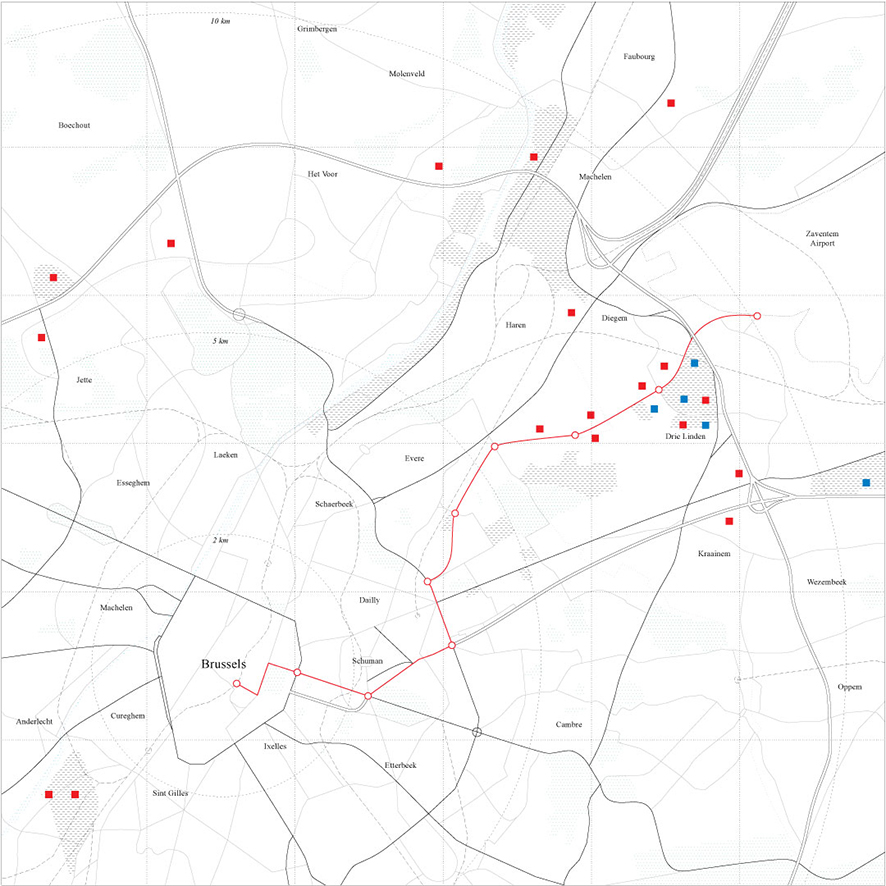

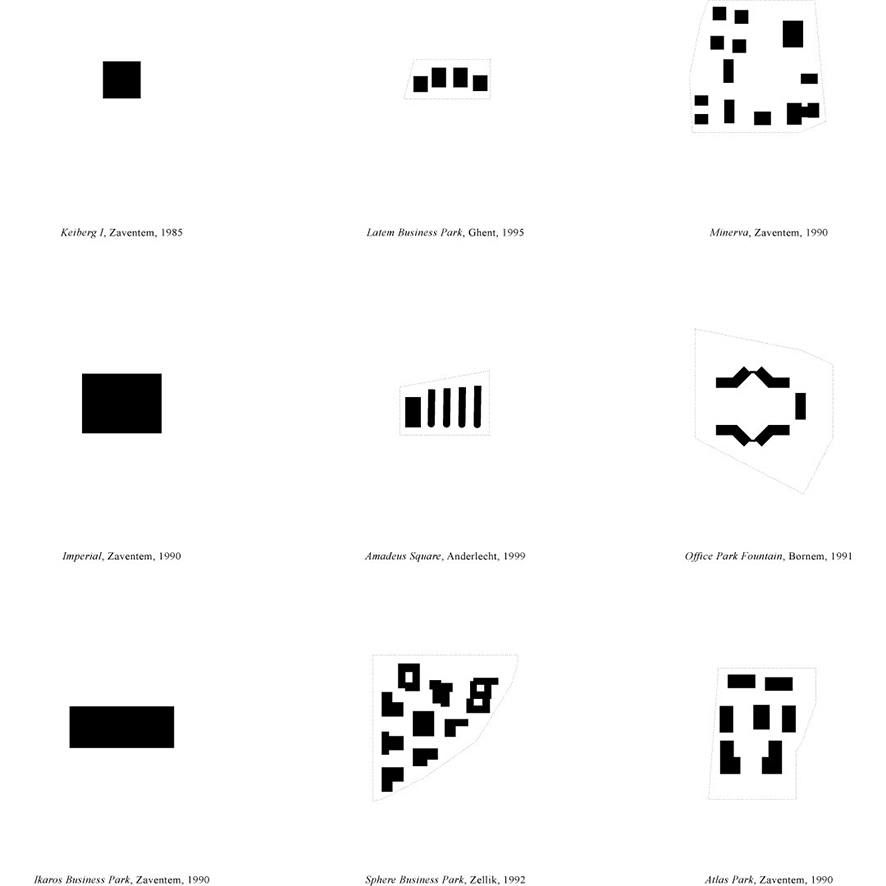

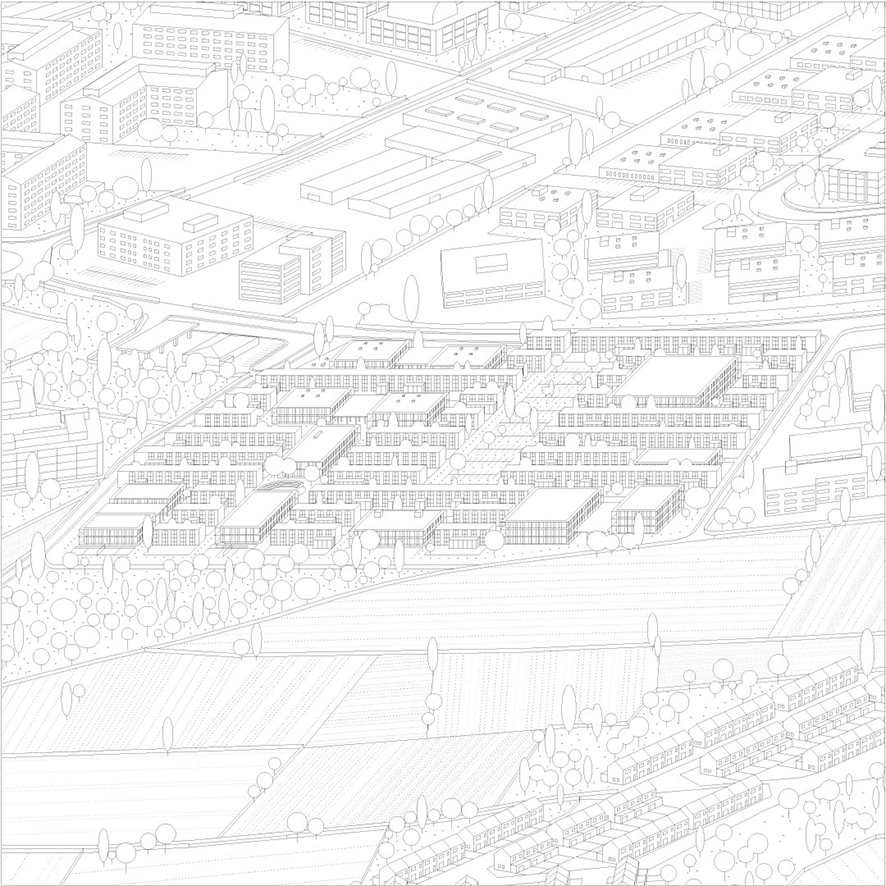

Due to Brussels’s role as an administrative and political center, which culminated in 2000 when the Belgian capital became the capital of the European Union, the city has witnessed a dramatic increase of office space over the past 30 years. Today, a large part of this stock is vacant. Two parts of the city make this crisis especially visible: Quartier Léopold, just east of the inner ring road, where almost all the major EU administrative buildings and associated organizations are located, and the office parks located in proximity to the international airport of Zaventem. We propose that these two sites be transformed into live/workspaces. These interventions should be understood as pilot projects that can be realized in different contexts, following three specific criteria.

Debido al papel de Bruselas como centro administrativo y político, que llegó a su culmen en el año 2000 cuando la ciudad belga se convirtió en la capital de la Unión Europea, la ciudad ha sido testigo de un dramático aumento del espacio de oficinas durante los últimos 30 años. Hoy en día, una gran parte de este stock está vacío. Dos partes de la ciudad hacen que esta crisis sea especialmente visible: el Quartier Léopold, justo al este de la carretera de circunvalación interior, donde se encuentran casi todos los principales edificios administrativos de la UE y las organizaciones asociadas, y los parques de oficinas ubicados cerca del aeropuerto internacional de Zaventem. Proponemos que estos dos sitios se transformen en espacios de vivir y trabajar. Estas intervenciones deben entenderse como proyectos piloto que pueden realizarse en diferentes contextos, siguiendo tres criterios específicos.

The first criterion is that the new housing is organized according to principles typical of the union or cooperative; inhabitants would take part in a collective ownership structure. This housing would be withdrawn from the commercial real estate market; the union prevents commercial takeover by ensuring that the housing remains a communal property, and that rents remain stable in the event that the original tenants move out.

El primer criterio es que la nueva vivienda se organice de acuerdo con los principios clásicos de una cooperativa; Los habitantes formarían parte en una estructura de propiedad colectiva. Esta vivienda sería retirada del mercado inmobiliario comercial; el sindicato evita la adquisición comercial asegurando que la vivienda siga siendo una propiedad comunal y que los alquileres se mantengan estables en caso de que los inquilinos originales se muden.

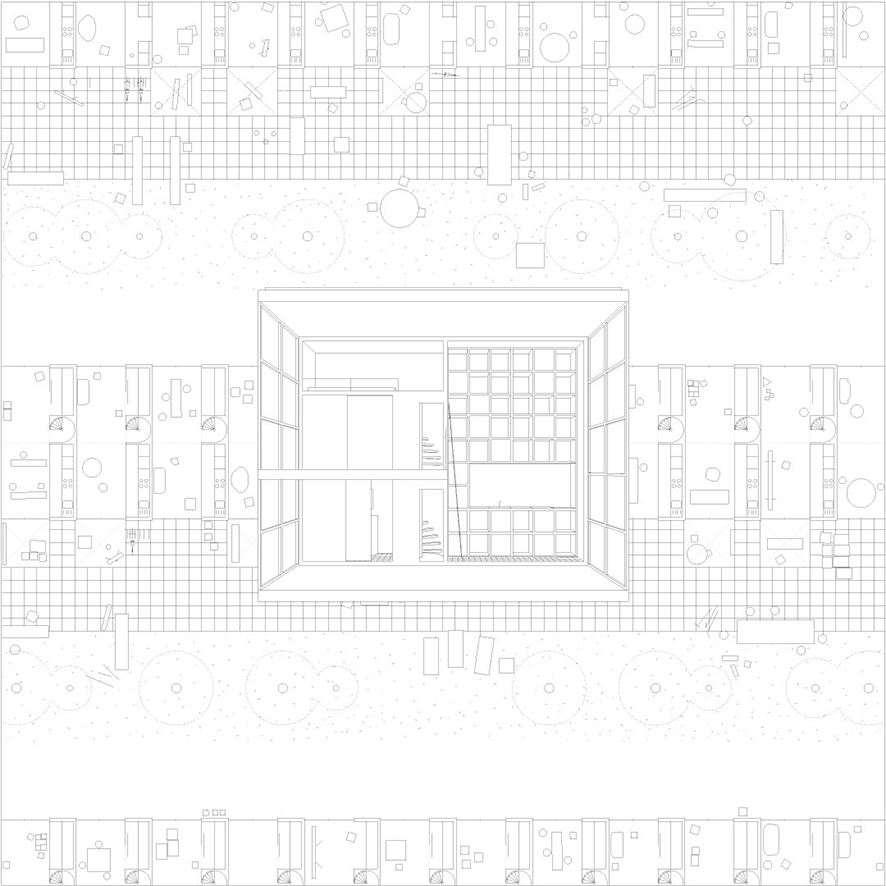

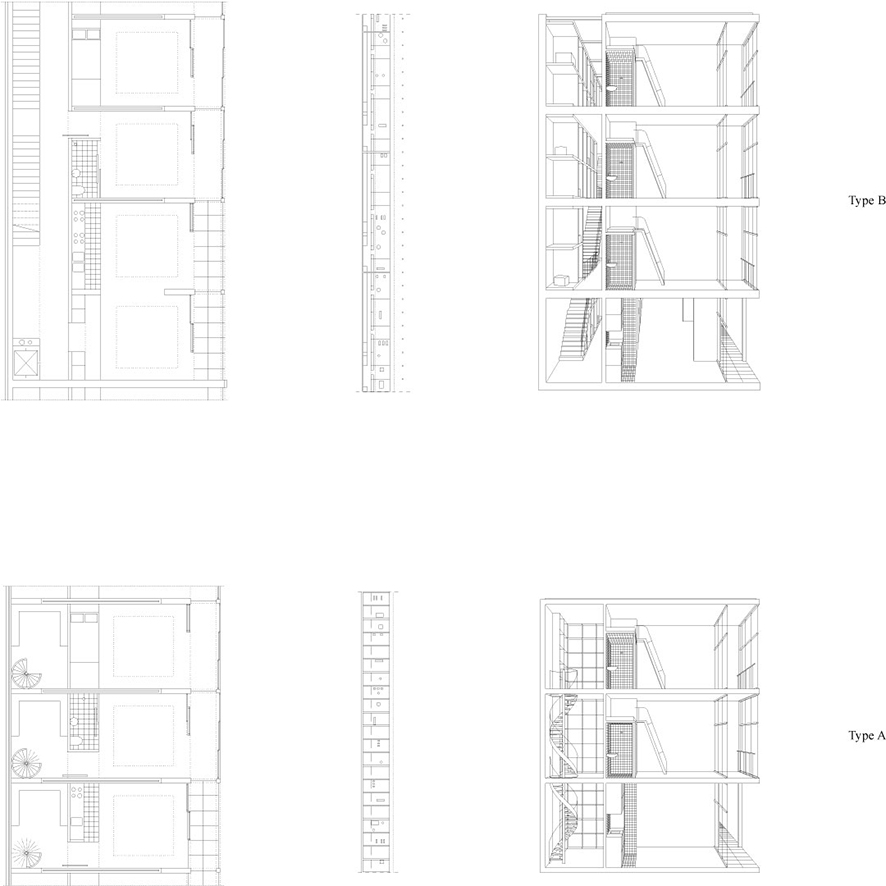

The second criterion is the organization of the housing around two spatial conditions: being alone and being together. Individual space is minimized so that one person can live in it comfortably, and collective space is increased to contain those functions usually squeezed into tiny apartments. In this way, domestic labor is exposed and shared by the collective and thus drastically reduced as an individual burden.

El segundo criterio es la organización de la vivienda en torno a dos condiciones espaciales: estar solo y estar acompañado. El espacio individual se minimiza para que una persona pueda vivir cómodamente dentro de él, y el espacio colectivo se incremente para contener aquellas funciones que normalmente se encuentran en pequeños apartamentos. De esta manera, el trabajo doméstico queda expuesto y compartido por el colectivo y, por lo tanto, se reduce drásticamente la carga individual.

The third criterion is to rethink the architecture of the finishings, which has a huge impact on costs in housing. Applying finishings typical of contemporary industrial buildings drastically reduces construction costs, but also enhances the quality of spaces by getting rid of redundant details. The goal is to maintain the zero-degree architecture of the office space. Moreover, industrial materials and solutions like concrete flooring, wooden partitions, and aluminum frames are easier to clean and maintain, and will thus reduce the effort required for maintenance.

El tercer criterio es repensar la arquitectura de los acabados que tiene un gran impacto en los costos de la vivienda. La aplicación de los acabados típicos de los edificios industriales contemporáneos reduce drásticamente los costos de construcción, pero también mejora la calidad de los espacios al deshacerse de los detalles redundantes. El objetivo es mantener la arquitectura de cero grados del espacio de oficinas. Además, los materiales y soluciones industriales como pisos de hormigón, particiones de madera y marcos de aluminio son más fáciles de limpiar y mantener, y por lo tanto reducirán el esfuerzo requerido para su mantenimiento.

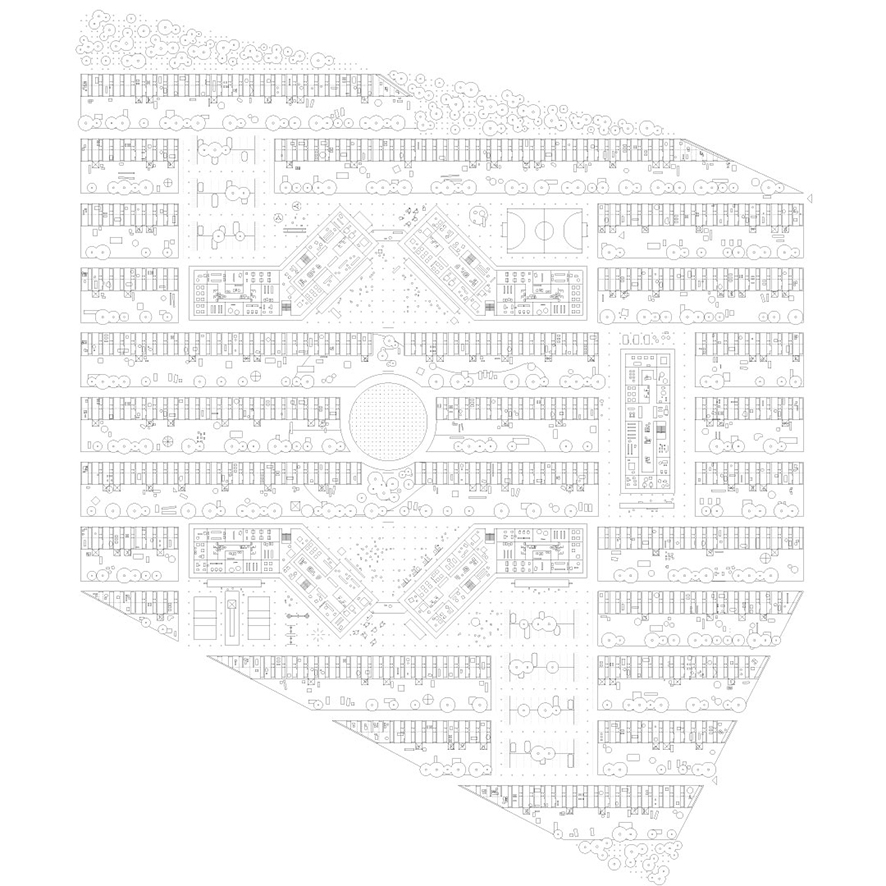

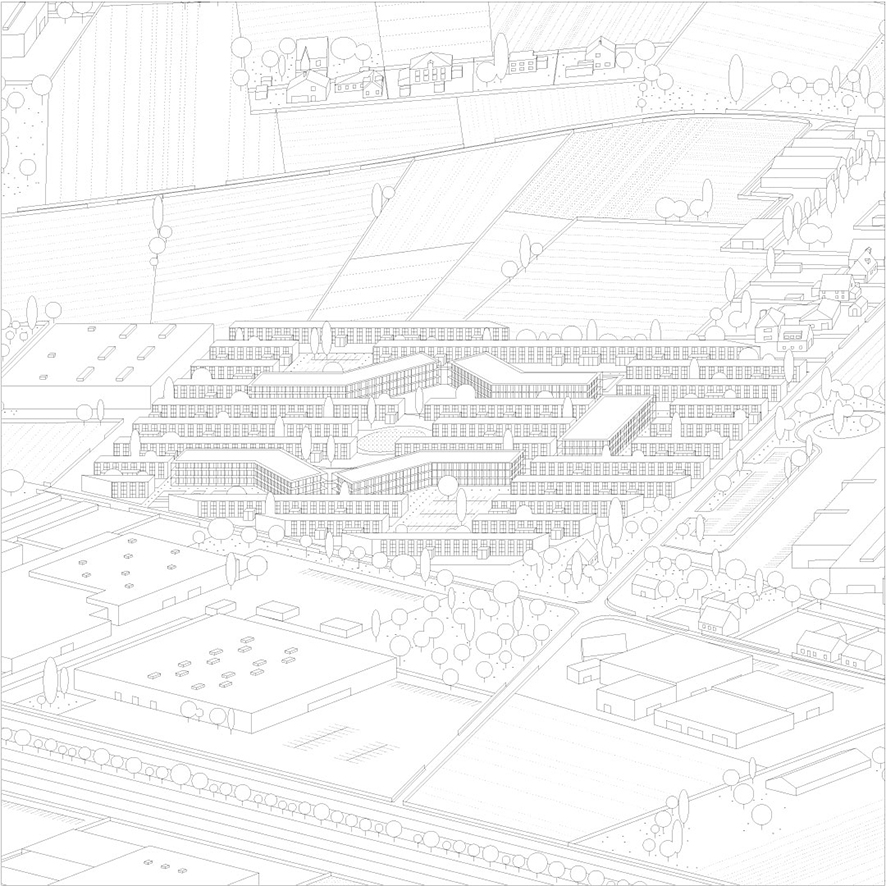

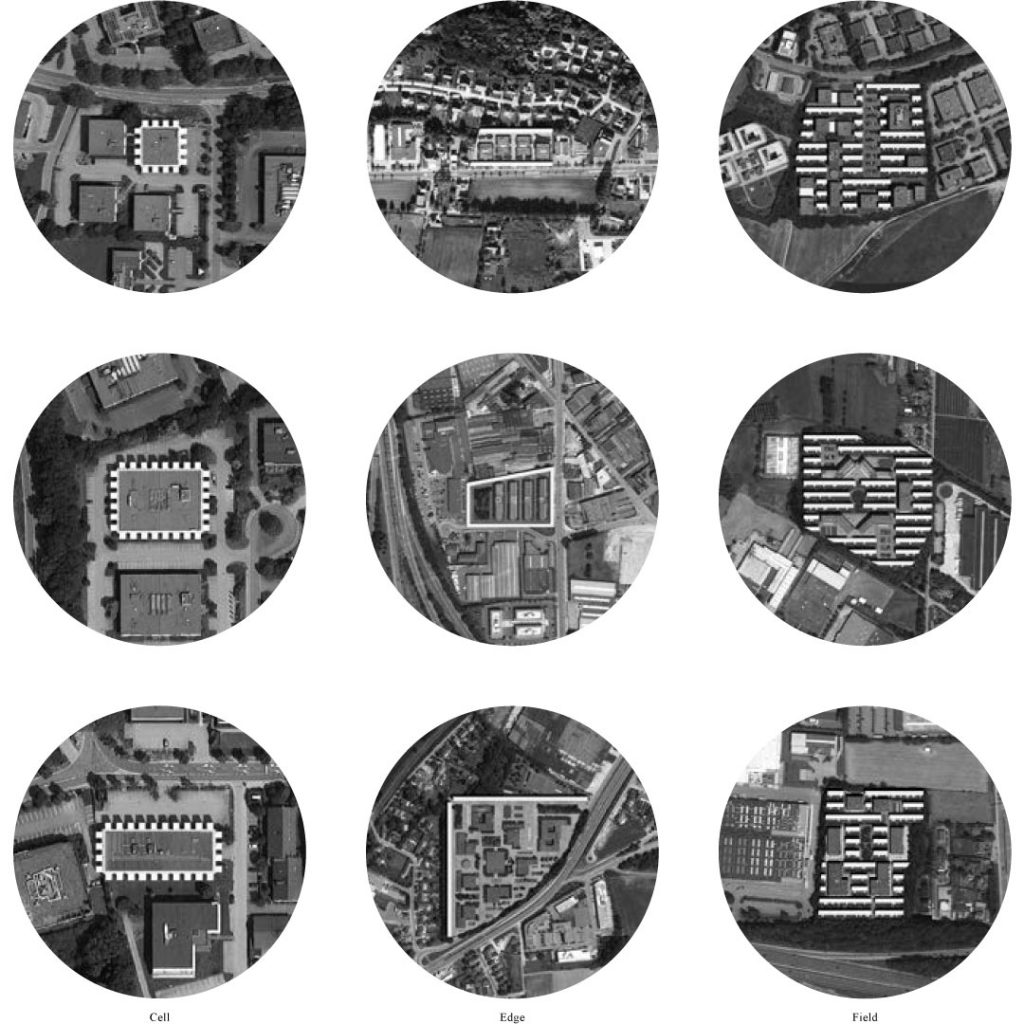

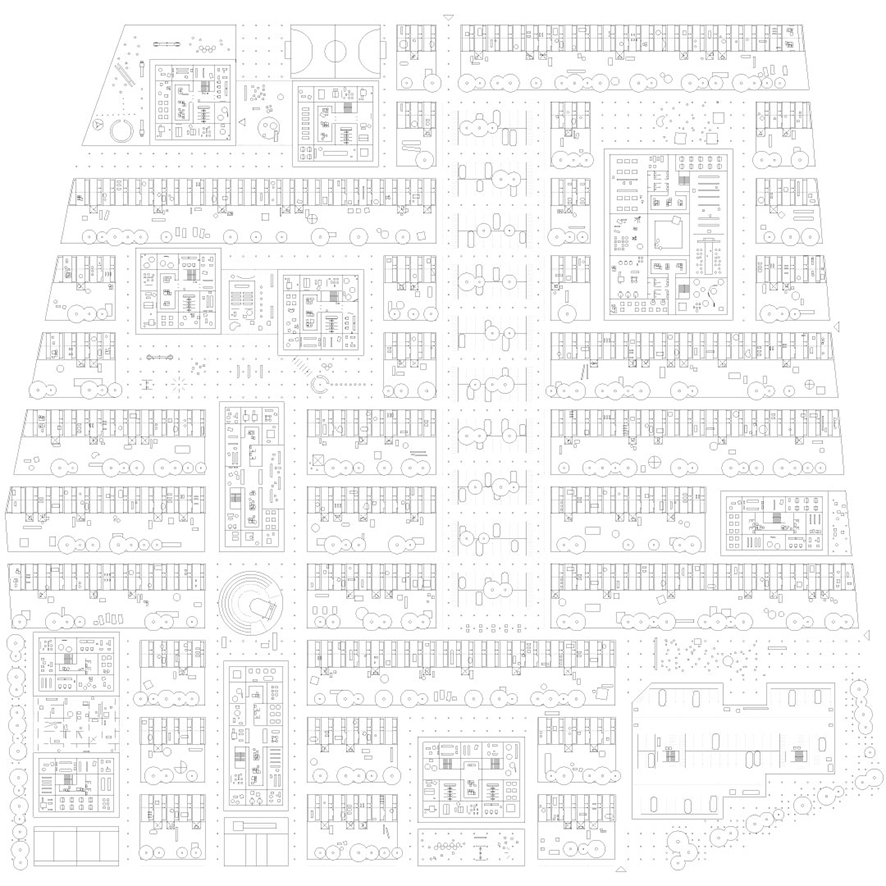

The office park can be considered the most emblematic form of “pastoral capitalism” that attempted to conceal the pressure of labor within the reassuring image of green landscape. While the office park was considered an attractive workplace in postwar suburban America, its import to Europe, beginning in the late 1970s, has been less successful. Rather than being developed by corporations, office parks in Europe are often initiated by developers as rentable spaces. Frequent turnover of tenants has made European office parks the utmost generic workplace. Often located on the outskirts of cities, they are always strategically connected to major infrastructures. It is precisely the generic character of these workplaces that makes them transformable. In the case of one single building, we propose to first demolish the non-load-bearing walls and the facade. Once the building is stripped of its facade and partitions, a circulation ring is added around the building, on which inhabitable cells are attached. In this way the interior of the office building can be freely organized according to different necessities. The abundance of space that can be found in office parks can benefit material forms of production that require a certain amount of square meters that are often not available within the dense fabric of city centers. Houses can thus be built within office parks either along their perimeters or even within the “parks” themselves, which often consist of abundant and underutilized parking lots. These houses can be conceived as flexible compositions of rooms that can be united into bigger units or remain independent cells. These rooms are no longer “domestic spaces,” but generic inhabitable spaces that can be used as a both houses or workplaces. The principle of “equal rooms” that can eventually be connected to form larger units is a way to counter the functional and gender specificity of domestic space, and to make housing adaptable for forms of life beyond the family. For this reason we aim toward a non-typological housing system in which space is reduced to the bare simplicity of the room, while services are contained within walls.

El parque de oficinas puede considerarse la forma más emblemática de “capitalismo pastoral” que intentó ocultar la presión del trabajo dentro de la imagen tranquilizadora del paisaje verde. Si bien el parque de oficinas se consideraba un lugar de trabajo atractivo en los Estados Unidos suburbanos de la posguerra, su importación a Europa, a partir de finales de la década de 1970, ha tenido menos éxito. En lugar de ser desarrollados por corporaciones, los parques de oficinas en Europa a menudo son iniciados por promotores como espacios rentables. La frecuente rotación de inquilinos ha hecho que los parques de oficinas europeos sean el lugar de trabajo más genérico. Situados a menudo en las afueras de las ciudades, siempre están conectados estratégicamente a las infraestructuras principales de la ciudad. Es precisamente el carácter genérico de estos lugares de trabajo lo que los hace transformables. En el caso de un solo edificio, proponemos demoler primero los muros que no soportan carga y la fachada. Una vez que el edificio está despojado de su fachada y particiones, se agrega un anillo de circulación alrededor del edificio, en el cual se adhieren celdas habitables. De esta manera, el interior del edificio de oficinas se puede organizar libremente según las diferentes necesidades. La abundancia de espacio que se puede encontrar en los parques de oficinas puede beneficiar las formas materiales de producción que requieren una cierta cantidad de metros cuadrados que a menudo no están disponibles dentro del denso tejido de los centros urbanos. Por lo tanto, las casas se pueden construir dentro de los parques de oficinas a lo largo de sus perímetros o incluso dentro de los “parques”, que a menudo consisten en estacionamientos abundantes y subutilizados. Estas casas se pueden concebir como composiciones flexibles de salas que se pueden unir en unidades más grandes o seguir siendo células independientes. Estas habitaciones ya no son “espacios domésticos”, sino espacios genéricos habitables que se pueden usar como casas o lugares de trabajo. El principio de “habitaciones iguales” que eventualmente se pueden conectar para formar unidades más grandes es una manera de contrarrestar la especificidad funcional y de género del espacio doméstico, y de hacer que la vivienda sea adaptable para formas de vida más allá de la familia. Por esta razón, apuntamos hacia un sistema de alojamiento no tipológico en el que el espacio se reduce a la simple simplicidad de la habitación, mientras que los servicios se encuentran dentro de las paredes.

Text by Dogma | Pier Vittorio Aureli and Martino Tattara

PROPOSAL FOR SPHERE BUSINESS PARK IN ZELLIK

- Total Area: 60.700 sqm.

- Gross floor area: 26.000 sqm

- Floor area ratio: 0.45

- Domestic unites: 420

PROPOSAL FOR MINERVA, ZAVENTEM

- Total Area:56.800 sqm.

- Gross floor area: 20.000 sqm

- Floor area ratio: 0.36

- Domestic unites: 300

PROPOSAL FOR FOUNTAIN PARK, BORNEM

- Total Area:69.000 sqm.

- Gross floor area: 32.500 sqm

- Floor area ratio: 0.50

- Domestic unites: 440