More and more frequently in recent years, many architectures have expressed a desire for reconciliation with the city, with the surroundings and with the existing buildings – as a search for legitimacy for an architecture that had otherwise lost all reference after the modernist movement was still justified by the ideology of the “new”. All too often, however, history was reduced to simple stylistic and evocative material; and this “delusion of history” (Vittorio Gregotti) seems to have become one of the characteristics of the design of these years. And it is this delusion that establishes a relationship of kinship, similarity and correspondence (sometimes sameness) with our past; the search, then, for adaptation rather than possible confrontation. In the effort to avoid the danger of confusing history with styles, the search for analogies with the past sometimes leads, as in the case of Leon Krier, to the rejection of new materials and modern technologies that have replaced artisanal construction techniques. There is an attempt to preserve the integrity of architecture in this way, but unfortunately only by repeating the past. Despite its retrograde tendency, this attitude reveals a real problem: for it is precisely the integrity of architecture that is increasingly threatened and rejected.

En los últimos años, muchas arquitecturas han expresado cada vez con más frecuencia un deseo de reconciliación con la ciudad, con el entorno y con los edificios existentes, como una búsqueda de legitimidad para una arquitectura que, por lo demás, había perdido toda referencia después de que el movimiento modernista siguiera justificándose con la ideología de lo “nuevo”. Sin embargo, con demasiada frecuencia la historia se redujo a un simple material estilístico y evocador; y este “engaño de la historia” (Vittorio Gregotti) parece haberse convertido en una de las características del diseño de estos años. Y es este delirio el que establece una relación de parentesco, de similitud y de correspondencia (a veces de semejanza) con nuestro pasado; la búsqueda, pues, de la adaptación más que de la posible confrontación. En el esfuerzo por evitar el peligro de confundir la historia con los estilos, la búsqueda de analogías con el pasado conduce a veces, como en el caso de Leon Krier, al rechazo de los nuevos materiales y de las tecnologías modernas que han sustituido a las técnicas de construcción artesanales. Se intenta así preservar la integridad de la arquitectura, pero desgraciadamente sólo repitiendo el pasado. A pesar de su tendencia retrógrada, esta actitud revela un verdadero problema: porque es precisamente la integridad de la arquitectura la que se ve cada vez más amenazada y rechazada.

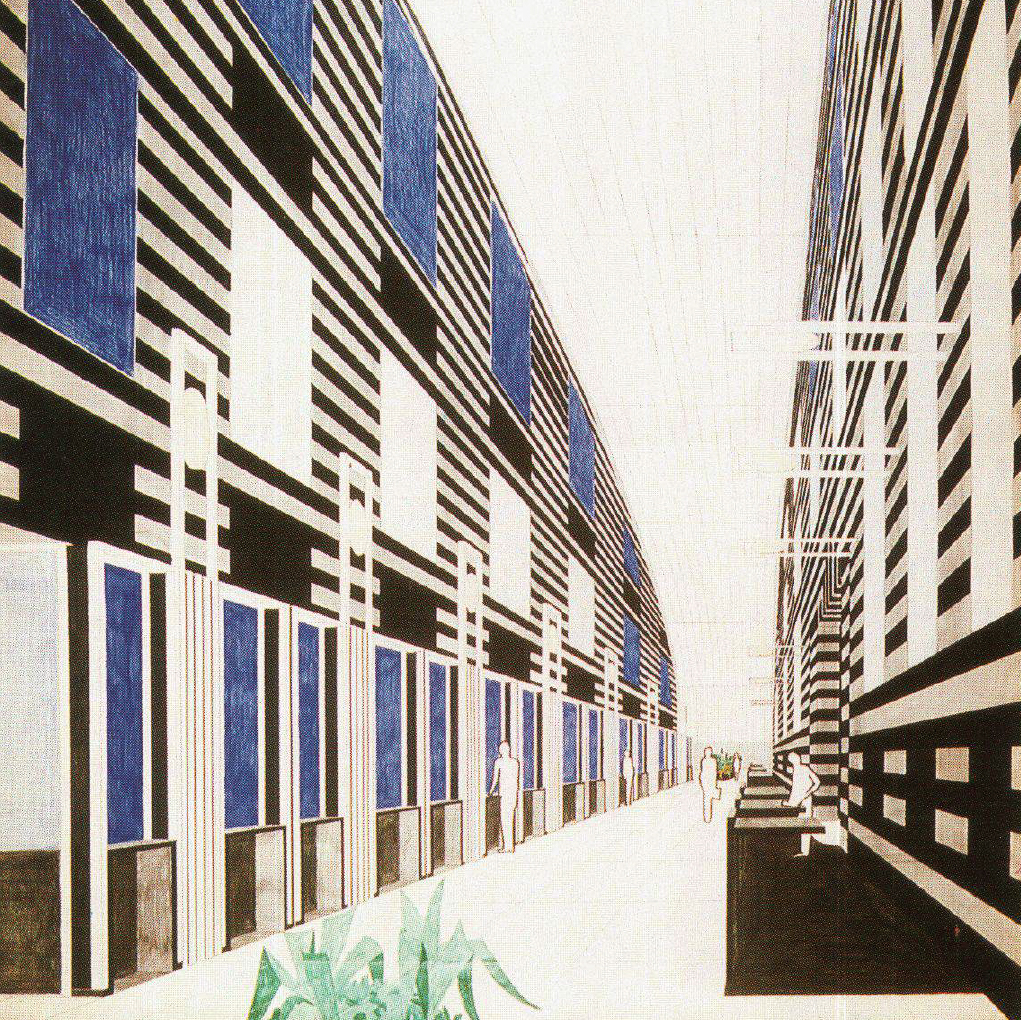

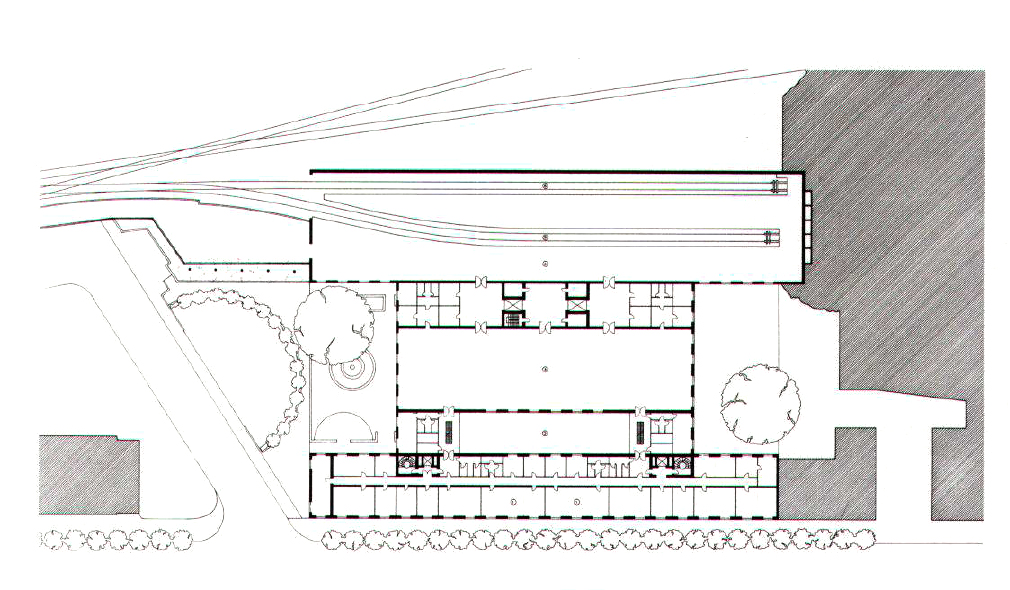

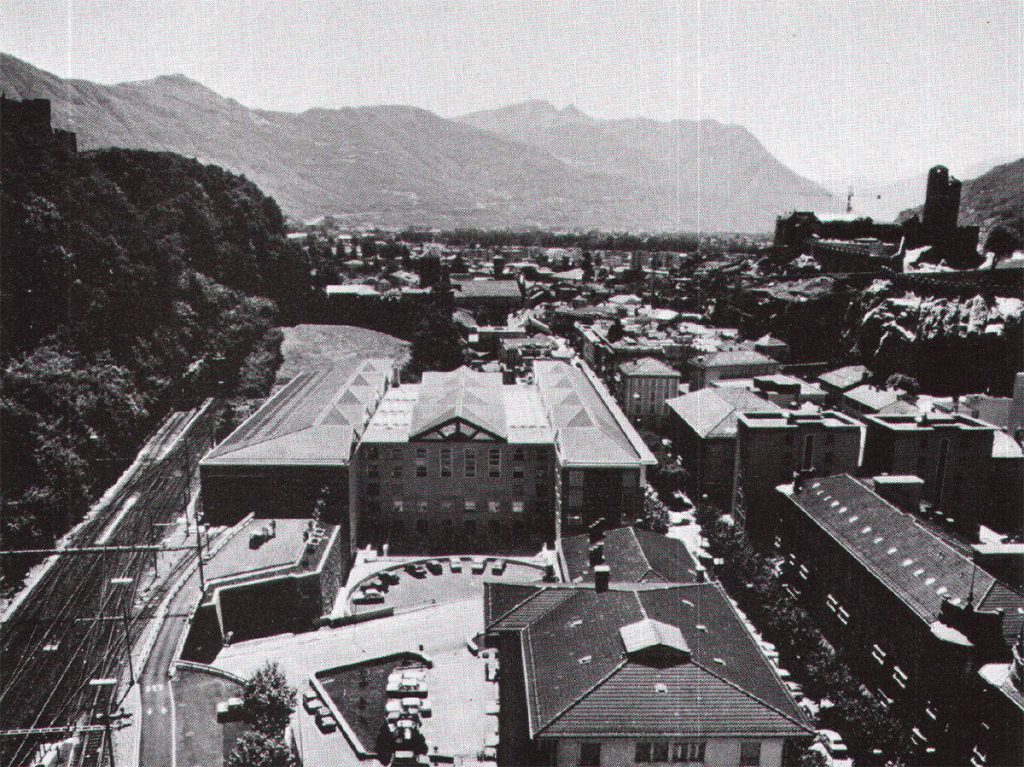

And this problem was also raised by the new post office in Bellinzona; the events surrounding this building, which began in 1968 with a competition, come to a first conclusion in 1977, with the commissioning of the architects Bianchi, Galfetti and Molina to draw only the façades. Today, the realised building is clear evidence of the refusal on the part of the planners to carry out a purely cosmetic operation on a given “technical volume”, while the clients wanted to reduce the role and task of the architect to this design operation.

Y este problema se planteó también en la nueva oficina de correos de Bellinzona; los acontecimientos en torno a este edificio, que se iniciaron en 1968 con un concurso, llegan a una primera conclusión en 1977, con el encargo a los arquitectos Bianchi, Galfetti y Molina de dibujar únicamente las fachadas. Hoy en día, el edificio realizado es una clara prueba del rechazo por parte de los proyectistas a realizar una operación puramente cosmética sobre un “volumen técnico” determinado, mientras que los clientes querían reducir el papel y la tarea del arquitecto a esta operación de diseño.

The project (designed in a very short time) was changed, improved and revised on site for years, in a constant bet to prove that architecture could be made for a post office building, despite all the bindings, limitations and difficulties, rather than just simple construction or disguising actions. Today, instead of an urban stage set, the Post Office represents a solution to the problem of incorporating a considerable volume within the historic core, without altering the existing fabric, but without, on the other hand, renouncing the expression of the new intervention. Unlike many other projects presented in the 1968 competition, the new building counters the ideology of the new as a value with the concept of belonging to a historical, geographical and physical context. However, the idea does not necessarily imply the acceptance of urban camouflage as the only path to follow. As in some of the most interesting contemporary projects, the relationship to the past and the city seems to invoke the dialectical lesson of Asplund’s Gothenburg townhouse extension rather than simpler lessons of assimilation.

El proyecto (diseñado en muy poco tiempo) fue cambiado, mejorado y revisado in situ durante años, en una apuesta constante por demostrar que se podía hacer arquitectura para un edificio de correos, a pesar de todas las ataduras, limitaciones y dificultades, más que simple construcción o acciones de disimulación. Hoy, en lugar de una escenografía urbana, la Oficina de Correos representa una solución al problema de incorporar un volumen considerable dentro del núcleo histórico, sin alterar el tejido existente, pero sin renunciar, por otra parte, a la expresión de la nueva intervención. A diferencia de muchos otros proyectos presentados en el concurso de 1968, el nuevo edificio contrapone a la ideología de lo nuevo como valor el concepto de pertenencia a un contexto histórico, geográfico y físico. Sin embargo, la idea no implica necesariamente la aceptación del camuflaje urbano como único camino a seguir. Como en algunos de los proyectos contemporáneos más interesantes, la relación con el pasado y la ciudad parece invocar la lección dialéctica de la ampliación de la casa adosada de Asplund en Gotemburgo en lugar de lecciones más simples de asimilación.

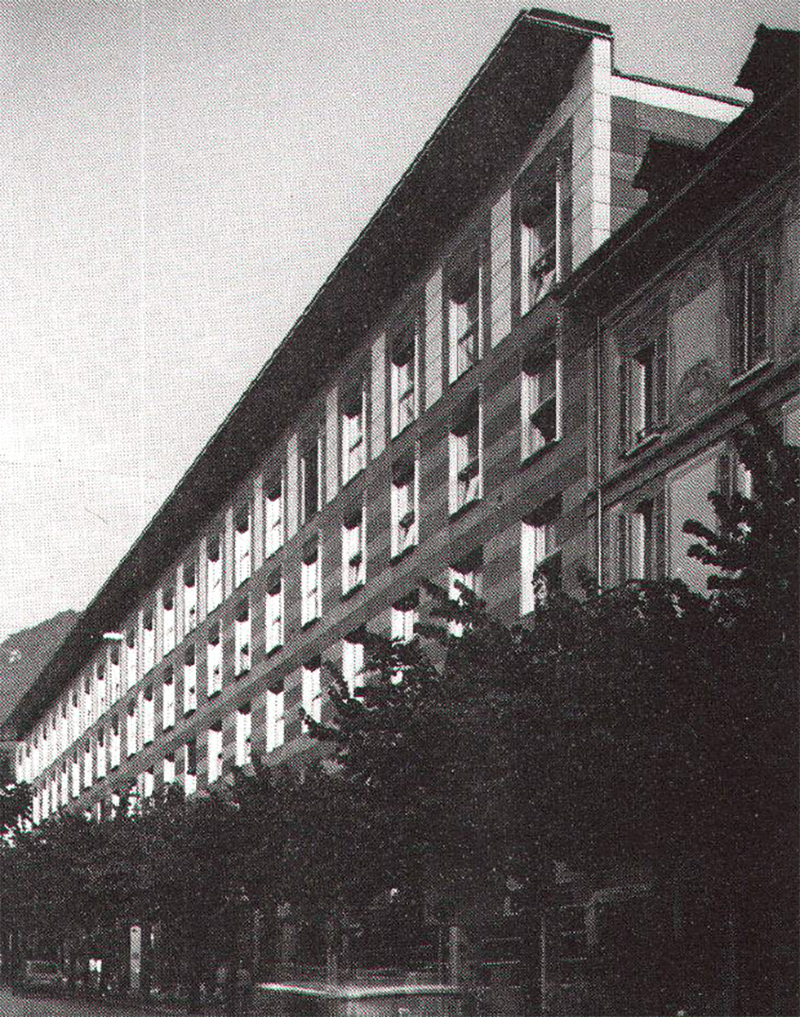

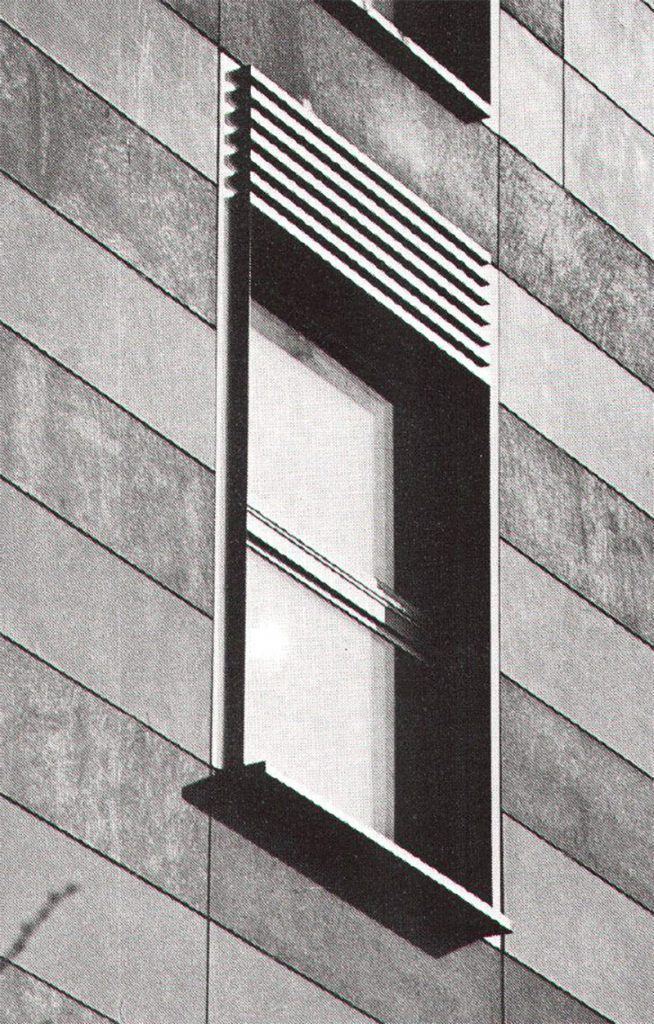

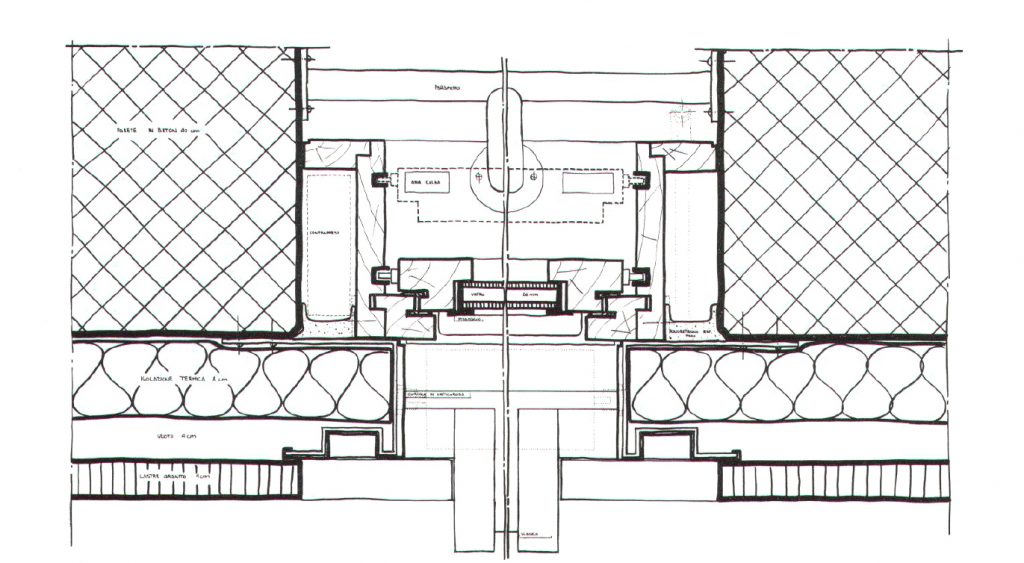

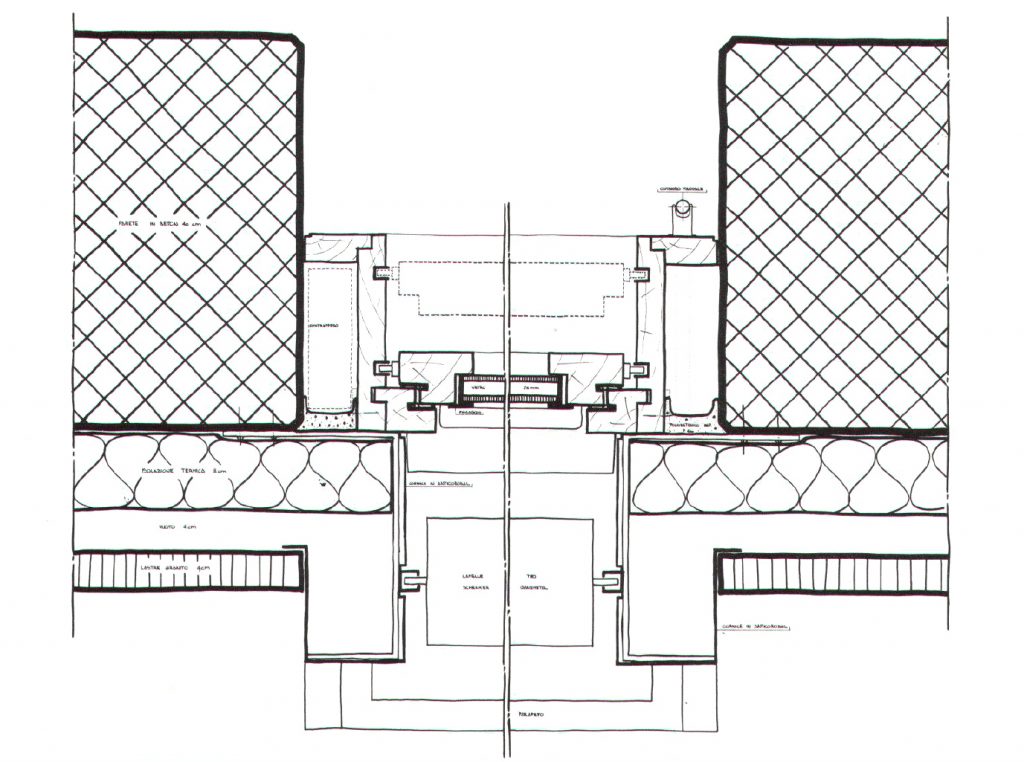

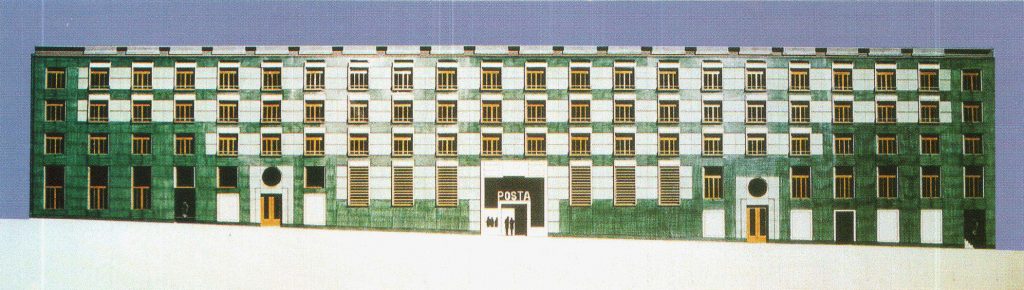

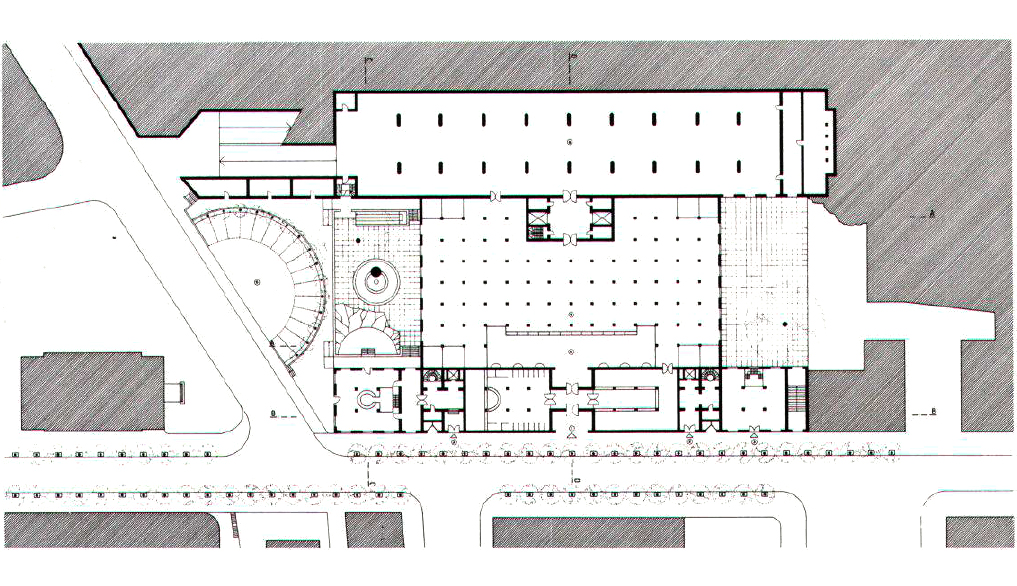

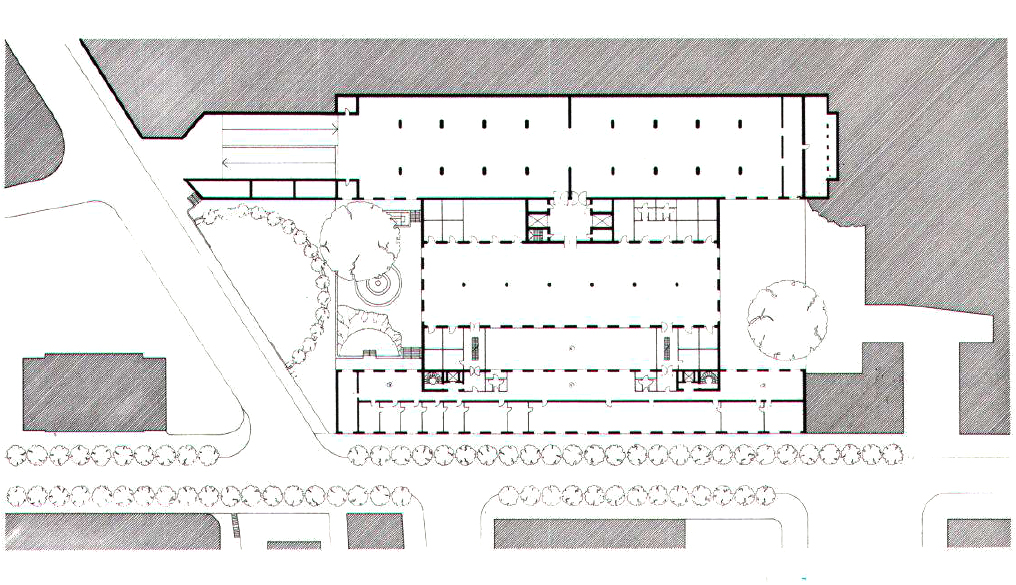

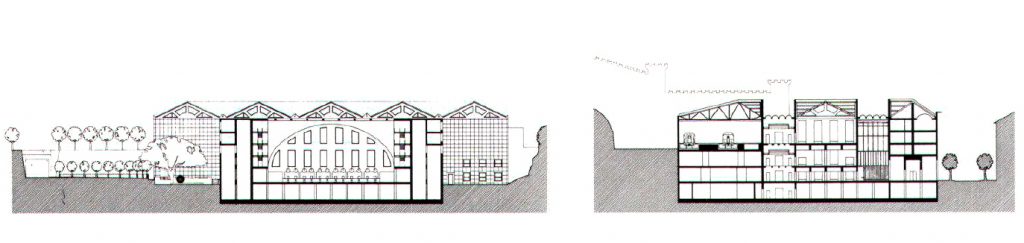

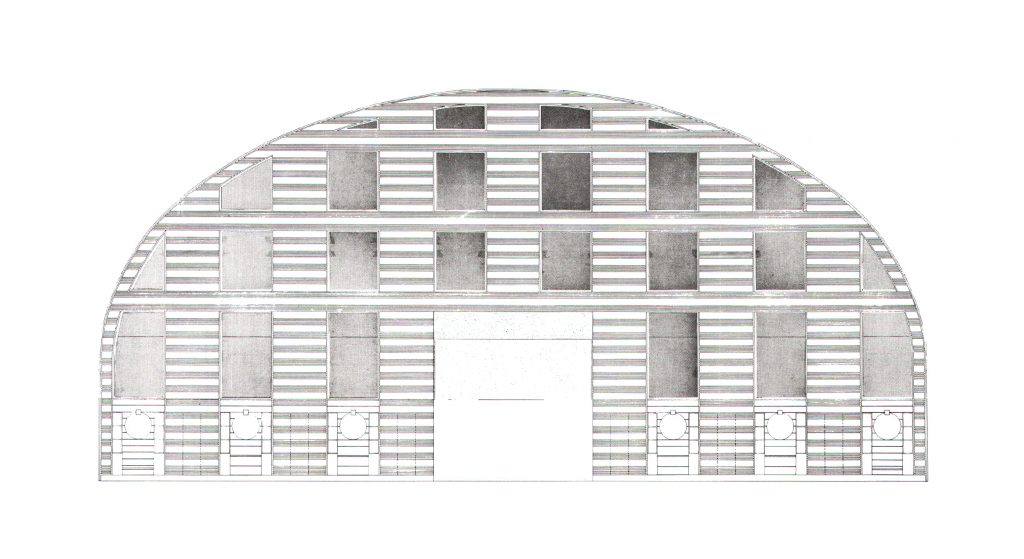

Economy and hierarchy are the main categories for understanding the building. A clear vision of urban development led to the avoidance of any architectural obtrusiveness. In the strategy identified in the plan, the two heads, the Station Square and the Piazza Indipendenza, form the urban poles. The problem of the post office building, which never offers a frontal view, is thus correctly reduced to the problem of restoring a continuous street. The economy of language, not of expression, on the other hand, is expressed in sparse and rather rare relations to the historic city. The façade, for example, does not live from traditional motifs but from the play of light; the tripartite division of the façade as well as the details of the window frames or the cornices are subject to this idea. The tripartition is achieved through the almost graphic use of the different materials: black marble for the plinth, alternating light and dark grey granite for the central band, white marble for the crowning. A drawn chiaroscuro overlaid with the play of light from the triangular aluminium cornices or the aluminium frames of the windows or the main cornice itself, the latter separated from the roof so that the light can penetrate in the morning. A façade that lives from the shades of colour and light, from midday to sunset. A façade that was not only devised to give the street back a continuity of rhythms, but above all to create a space, the street space. This is the only way to understand the projecting main cornice, which not only crowns the building but also closes off the street space.

La economía y la jerarquía son las principales categorías para entender el edificio. Una visión clara del desarrollo urbano llevó a evitar cualquier obtrusismo arquitectónico. En la estrategia identificada en el plan, las dos cabezas, la plaza de la Estación y la plaza Indipendenza, forman los polos urbanos. El problema del edificio de Correos, que nunca ofrece una vista frontal, se reduce así correctamente al problema de la restauración de una calle continua. En cambio, la economía de lenguaje, no de expresión, se expresa en relaciones escasas y bastante raras con la ciudad histórica. La fachada, por ejemplo, no vive de los motivos tradicionales, sino del juego de la luz; la división tripartita de la fachada, así como los detalles de los marcos de las ventanas o las cornisas, están sujetos a esta idea. La tripartición se consigue mediante el uso casi gráfico de los distintos materiales: mármol negro para el zócalo, granito gris claro y oscuro alternado para la banda central, mármol blanco para el coronamiento. Un claroscuro dibujado que se superpone al juego de luces de las cornisas triangulares de aluminio o de los marcos de aluminio de las ventanas o de la propia cornisa principal, esta última separada del tejado para que la luz penetre por la mañana. Una fachada que vive de los matices del color y de la luz, desde el mediodía hasta el atardecer. Una fachada que no sólo fue concebida para devolver a la calle una continuidad de ritmos, sino sobre todo para crear un espacio, el espacio de la calle. Sólo así se entiende el saliente de la cornisa principal, que no sólo corona el edificio sino que cierra el espacio de la calle.

A quiet reminiscence of Vienna often inserts itself into this play, not only in the façade drawing, but also in the use of materials and above all in the definition of the interior spaces. After the death of Le Corbusier, the architectural discussion conducted by some Ticino architects with the help of history had also touched Vienna. And the Viennese lesson is particularly present in two buildings of the 1970s: the Macconi Centre in Lugano by Vacchini and the State Bank in Fribourg by Botta. These two buildings are of great importance because of their urban character and the reflections on the façade. But rather than in the use of certain materials or certain details or in the treatment of the façade, the Viennese influence (especially the Postbank of Otto Wagner) in the the basic architectural approach of the in Bellinzona, in that the expression of the public dimension of the of the intervention does not appear on the outside, but the large space of the counter hall, which is of the counter hall, illuminated from above by the zenith light. The post office façade is therefore only a “door leading to the hall”. If this is the expression of public space, the expression of the technical space of the post office of the distribution hall, is defined in the steel of the roof. The roof forms together with the façade along the street the main element for the connection to the surroundings. The use of the hipped roof is in harmony with the lack of any unusual intervention and and with the desire to use this opportunity as an element of the reconstruction of the city.

Una tranquila reminiscencia de Viena se inserta a menudo en esta obra, no sólo en el dibujo de la fachada, sino también en el uso de los materiales y, sobre todo, en la definición de los espacios interiores. Tras la muerte de Le Corbusier, la discusión arquitectónica llevada a cabo por algunos arquitectos del Tesino con la ayuda de la historia ha tocado también a Viena. Y la lección vienesa está especialmente presente en dos edificios de los años 70: el Centro Macconi de Lugano, de Vacchini, y el Banco del Estado de Friburgo, de Botta. Estos dos edificios son de gran importancia por su carácter urbano y los reflejos en la fachada. Pero más que en el uso de ciertos materiales o de ciertos detalles o en el tratamiento de la fachada, la influencia vienesa (especialmente el Postbank de Otto Wagner) en el planteamiento arquitectónico básico del en Bellinzona, en el sentido de que la expresión de la dimensión pública de la de la intervención no aparece en el exterior, sino el gran espacio del vestíbulo del mostrador, iluminado desde arriba por la luz cenital. Por tanto, la fachada de la oficina de correos no es más que una “puerta que conduce al vestíbulo”. Si esta es la expresión del espacio público, la expresión del espacio técnico de la oficina de correos del hall de distribución, se define en el acero definido en la estructura de la cubierta. La cubierta forma, junto con la fachada a lo largo de la calle, el elemento principal de conexión con el entorno. El uso de la cubierta a cuatro aguas está en armonía con la falta de cualquier intervención inusual y con el deseo de utilizar esta oportunidad como un elemento de la reconstrucción de la ciudad.

It is indeed not possible in Bellinzona, the city dominated by two castles and therefore often seen from above, to neglect the importance of the roofing in order to favour instead the construction solely of the street space. The roof of the post office thus assumes the role of a second building façade. It now also seems clear why Galfetti introduced the norm imposing the use of the hipped roof and the brick tiles in the plan of the historic centre, as one of the few necessary, if insufficient, rules to preserve the homogeneity of the historic city. A context which is nothing other than history history with its solidified expression: the city with its rooftops, the from the Castel Grande, which dominates Bellinzona. In contrast to much of today’s architecture, which “walks in the present” but only sees the past, this work, despite some uncertainties, testifies to a vitality and an enthusiasm, a generosity to risk and an unlimited curiosity. A curiosity that relates to our dealings with the past, that is directed above all to our present as the cornerstone of all future action.

En efecto, no es posible en Bellinzona, ciudad dominada por dos castillos y, por tanto, vista a menudo desde arriba, descuidar la importancia de la cubierta para favorecer en cambio la construcción únicamente del espacio de la calle. El tejado de la oficina de correos asume así el papel de una segunda fachada del edificio. Ahora también parece claro por qué Galfetti introdujo la norma que impone el uso del tejado a cuatro aguas y las tejas de ladrillo en el plano del centro histórico, como una de las pocas reglas necesarias, aunque insuficientes, para preservar la homogeneidad de la ciudad histórica. Un contexto que no es otra cosa que la historia con su expresión solidificada: la ciudad con sus tejados, el del Castel Grande, que domina Bellinzona. En contraste con gran parte de la arquitectura actual, que “camina en el presente” pero sólo ve el pasado, esta obra, a pesar de algunas incertidumbres, da testimonio de una vitalidad y un entusiasmo, de una generosidad para arriesgar y de una curiosidad ilimitada. Una curiosidad que se refiere a nuestro trato con el pasado, que se dirige sobre todo a nuestro presente como piedra angular de toda acción futura.

Text by Mirko Zardini

VIA:

Werk, Bauen und Wohnen 72, 1985