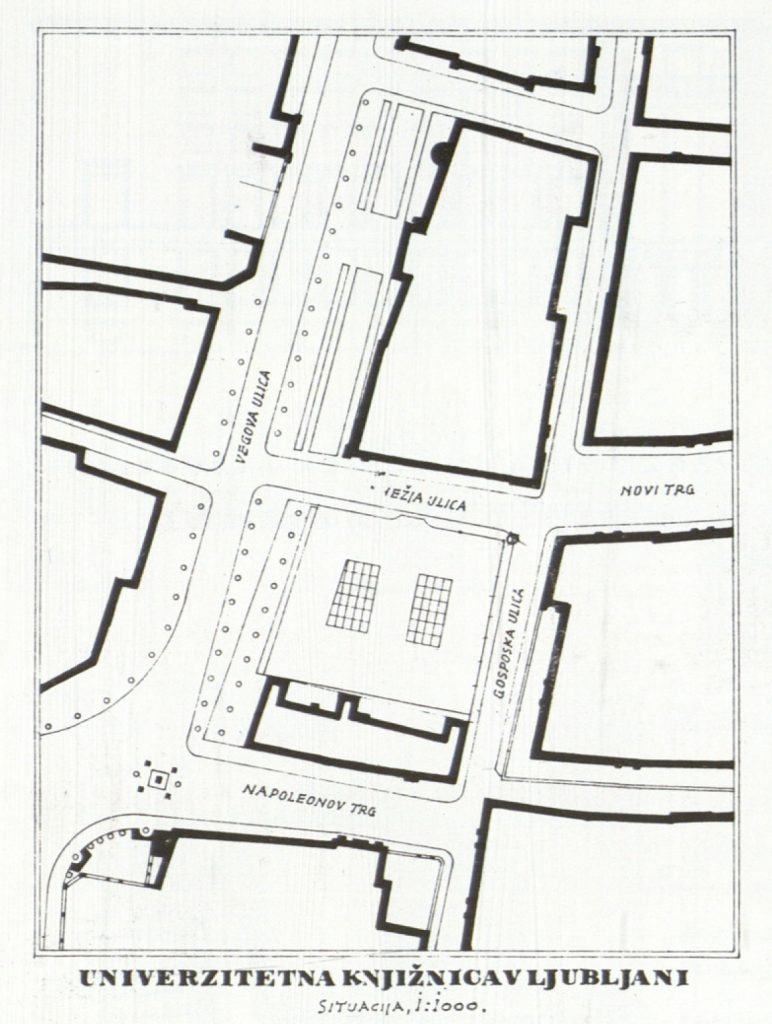

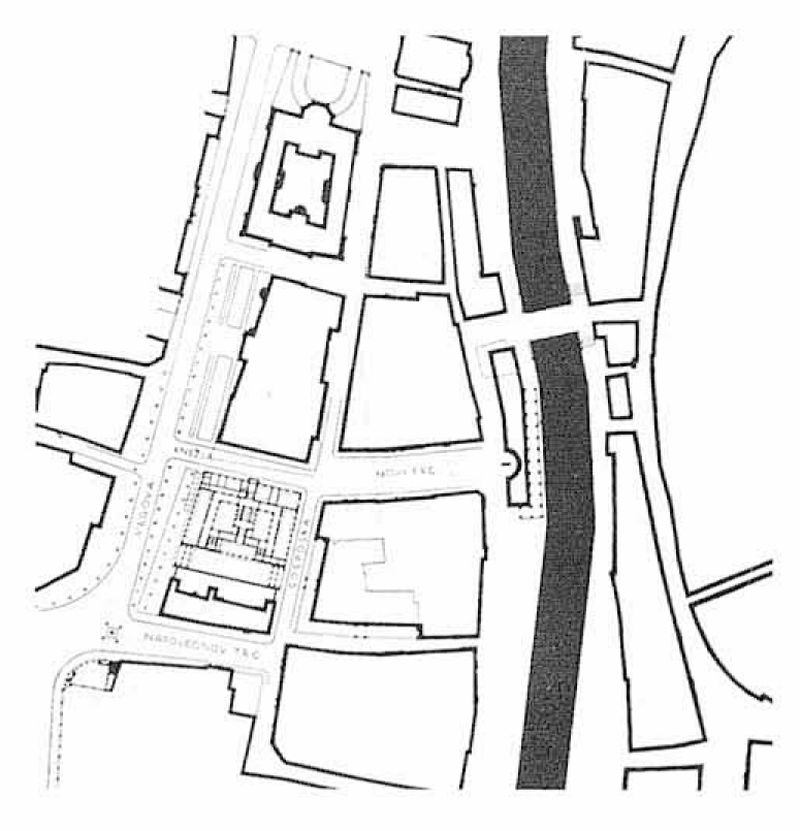

The building is on the same piece of land where the late-Renaissance Anersperg Palace had been torn down after being partially destroyed by the 1895 earthquake Plecnik believed that something important had to be built here for several reasons. One was the location between Vegova and Gospoka streets around the open Novi-Trg space and another was lo replace the impressive building which had just been torn down. In 1931 Plecnik started to consider the possibilities of a National Library on this plot. After having taken into account all of the architectural factor and their importance , in this beloved city. He began by making a few basic sketches which he then presented to the local authorities for their approval and needed support in order to gel the financial aid from the Yugoslav Federal Government on Belgrade.

El edificio está en el mismo terreno donde el Palacio de Anersperg, de finales del Renacimiento, fue derribado después de ser parcialmente destruido por el terremoto de 1895. Plecnik creía que algo importante tenía que ser construido aquí por varias razones. Una era la ubicación entre las calles Vegova y Gospoka alrededor del espacio abierto de Novi-Trg y otra era para reemplazar el impresionante edificio que acababa de ser derribado. En 1931, Plecnik comenzó a considerar las posibilidades de una Biblioteca Nacional en este terreno. Después de haber tenido en cuenta todos los factores arquitectónicos y su importancia, en esta amada ciudad. Comenzó por hacer algunos bocetos básicos que luego presentó a las autoridades locales para su aprobación y necesitó apoyo para conseguir la ayuda financiera del Gobierno Federal Yugoslavo en Belgrado.

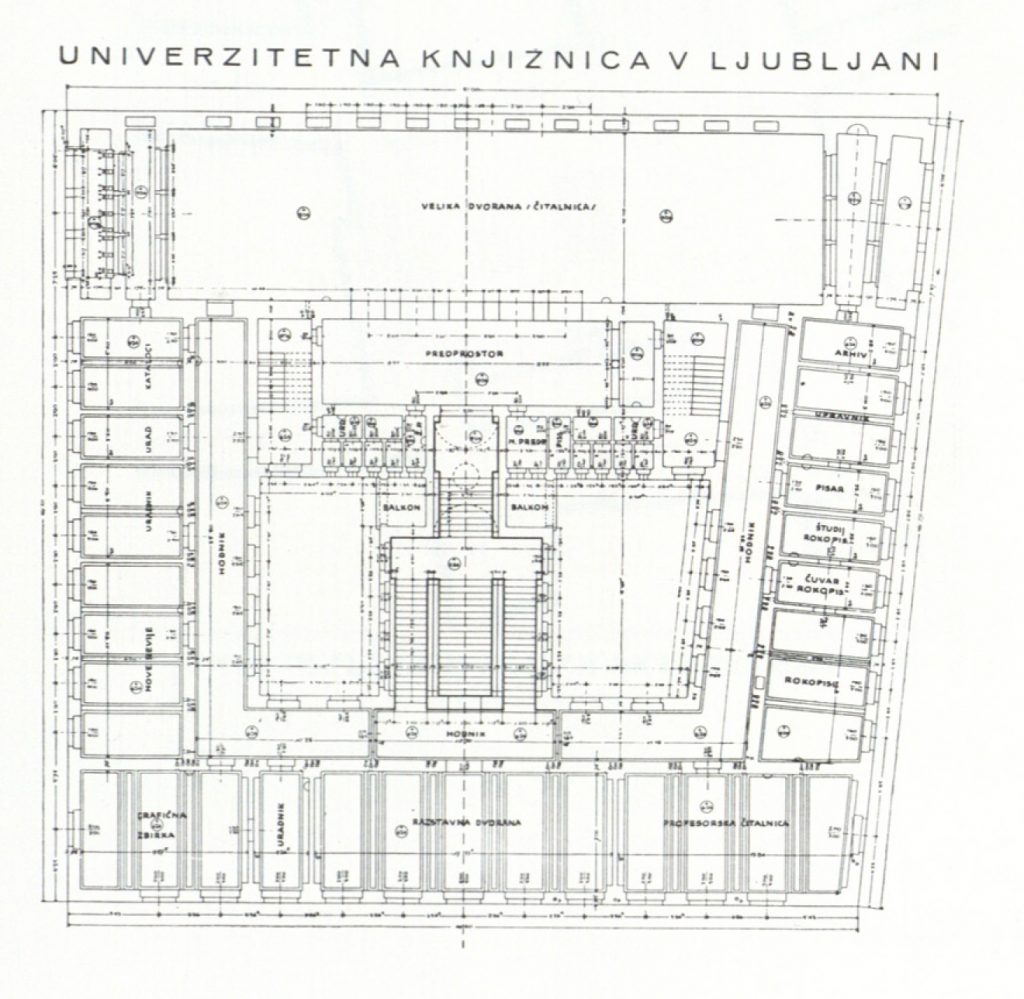

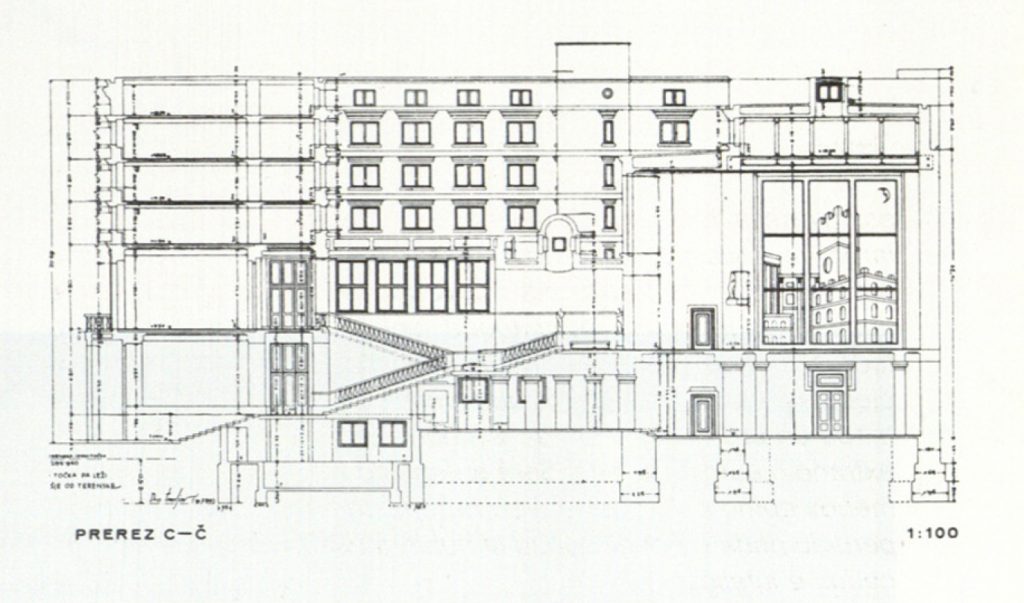

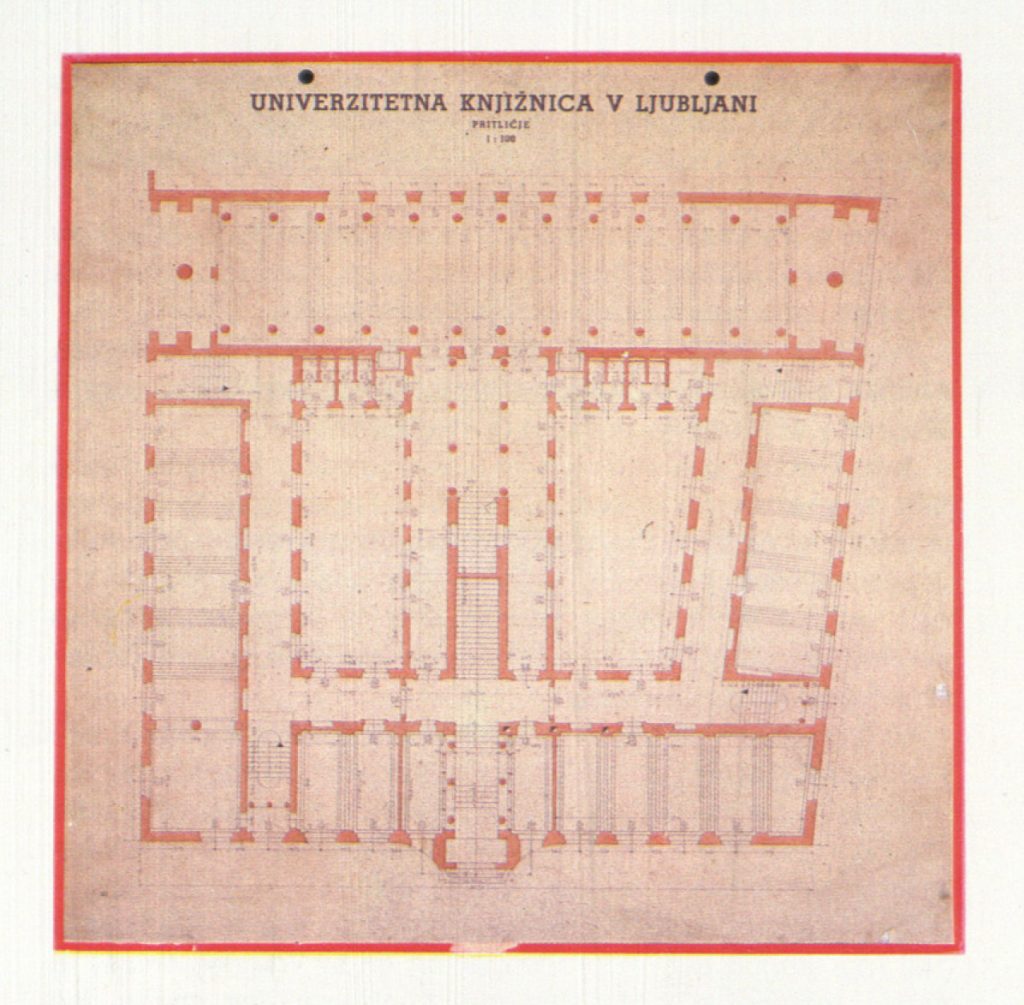

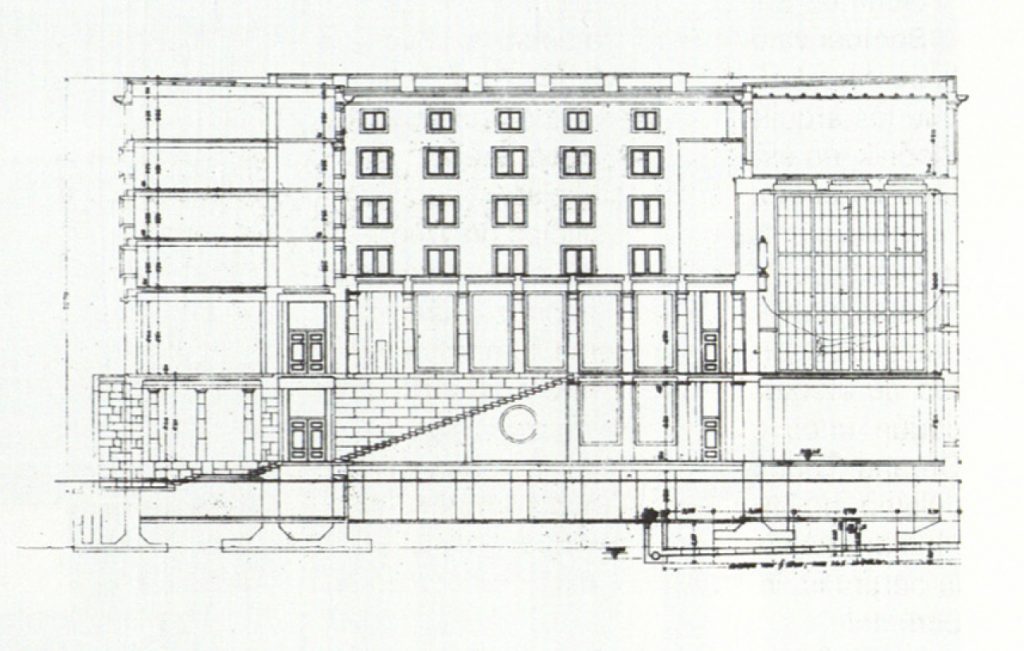

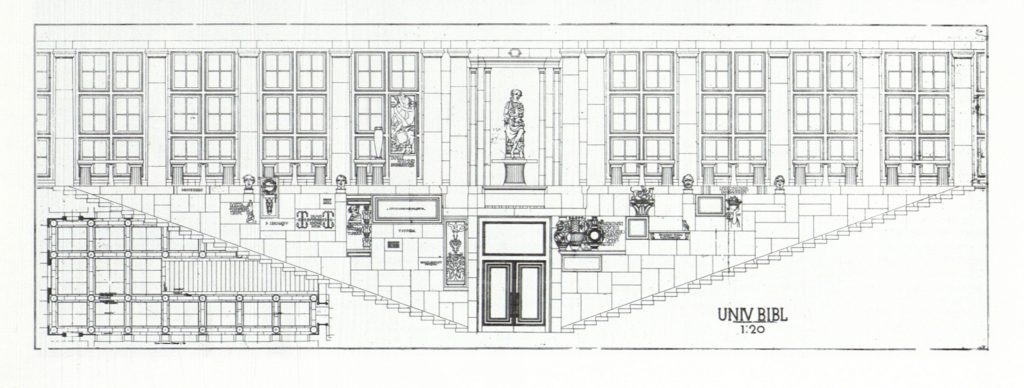

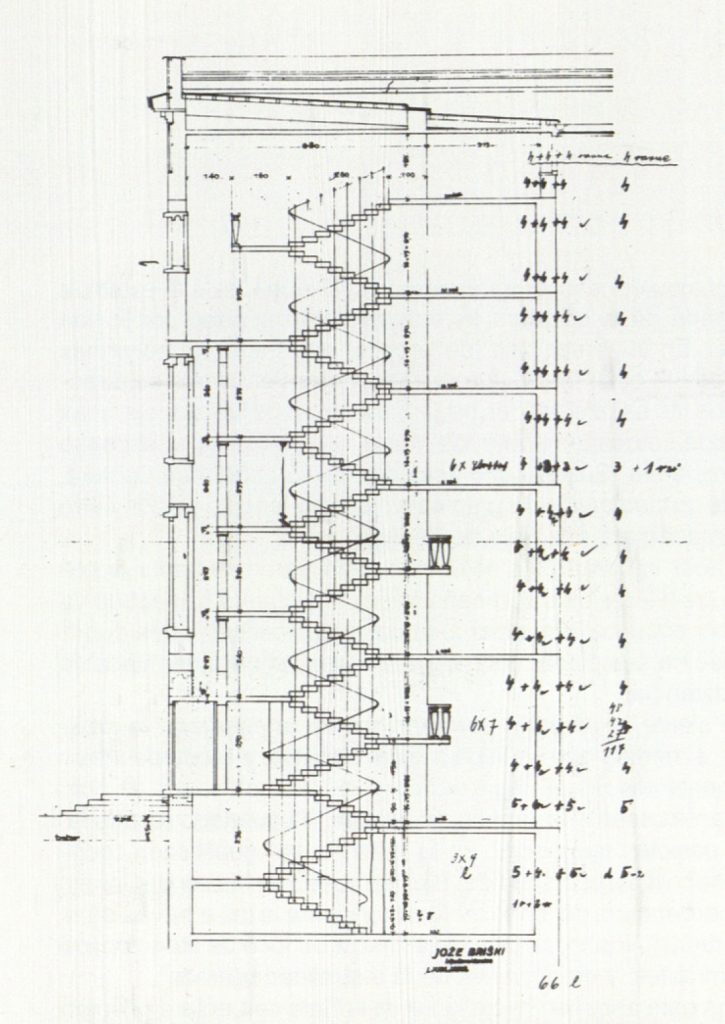

The new building, in addition to housing the National Library, had to accommodate a series of rooms and lecture halls for the University, which made the programme at least more complex by mixing two uses, and in any case made the library only a part of the building and not the whole. Already in the first project, Plecnik proposed a large cubic building with a cortile interior, in the manner of an Italian-style palazzo. The large reading room is located laterally, right on the side of the square on the floor, which makes the party wall with the annex building that completes the block. The entrance, on Calle Knezja, is on the opposite side, so that to reach the Reading Room in a straight line, it is necessary to cross the cortile; Plecnik therefore places a large staircase in the middle of this cortile, in one run, which. halfway up, forks into two opposite runs; one that continues into the Reading Room and another two parallel ones, which turn to the side above the entrance. In this way, Plecnik highlights the need to serve the two pre-established uses: library and university classrooms.

El nuevo edificio, además de alojar la Biblioteca Nacional, debía acomodar una serie de estancias y aulas para la Universidad, lo que hacía que el programa fuera, cuando menos, más complejo, al mezclar dos usos, y en cualquier caso, hacía que la biblioteca fuera sólo una parte del edificio y no la totalidad. Ya en el primer proyecto, Plecnik plantea un gran edificio cúbico. con un cortile interior, a modo de palazzo a la italiana. La gran sala de lectura, se ubica lateralmente, justo en el lado del cuadrado de la planta, que hace la medianera con el edificio anexo que completa la manzana. La entrada, por la calle Knezja, queda en el lado opuesto, de modo que para llegar a la Sala de Lectura en línea recta, es preciso atravesar el cortile; por ello Plecnik coloca un gran ascenso de escaleras, en medio de este cortile, de una tirada, que. a mitad de camino se bifurca en dos tiradas opuestas; una que continúa hacia la Sala de Lectura y otras dos paralelas, que se vuelven hacia el lado sobre la entrada. De este modo Plecnik pone de manifiesto la necesidad de servir a los dos usos va preestablecidos de partida: biblioteca nacional y aulas universitarias.

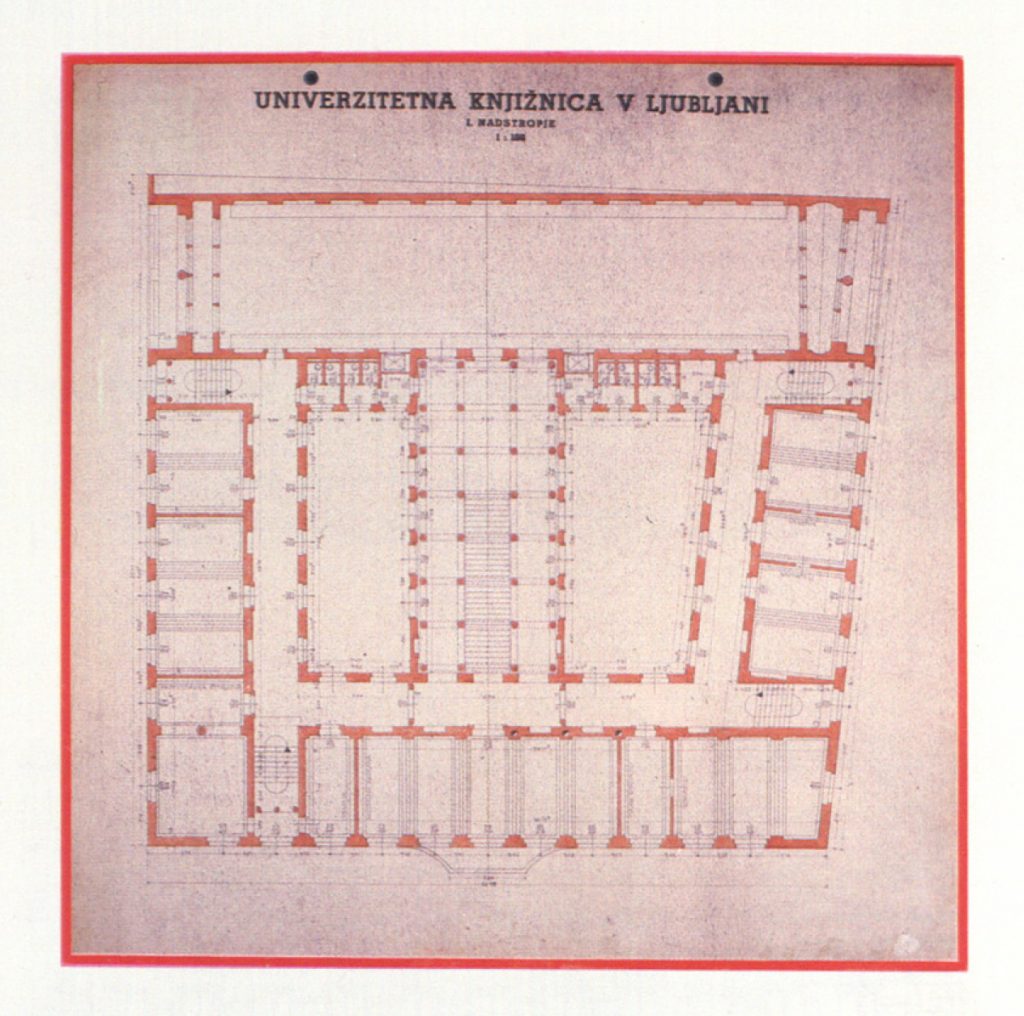

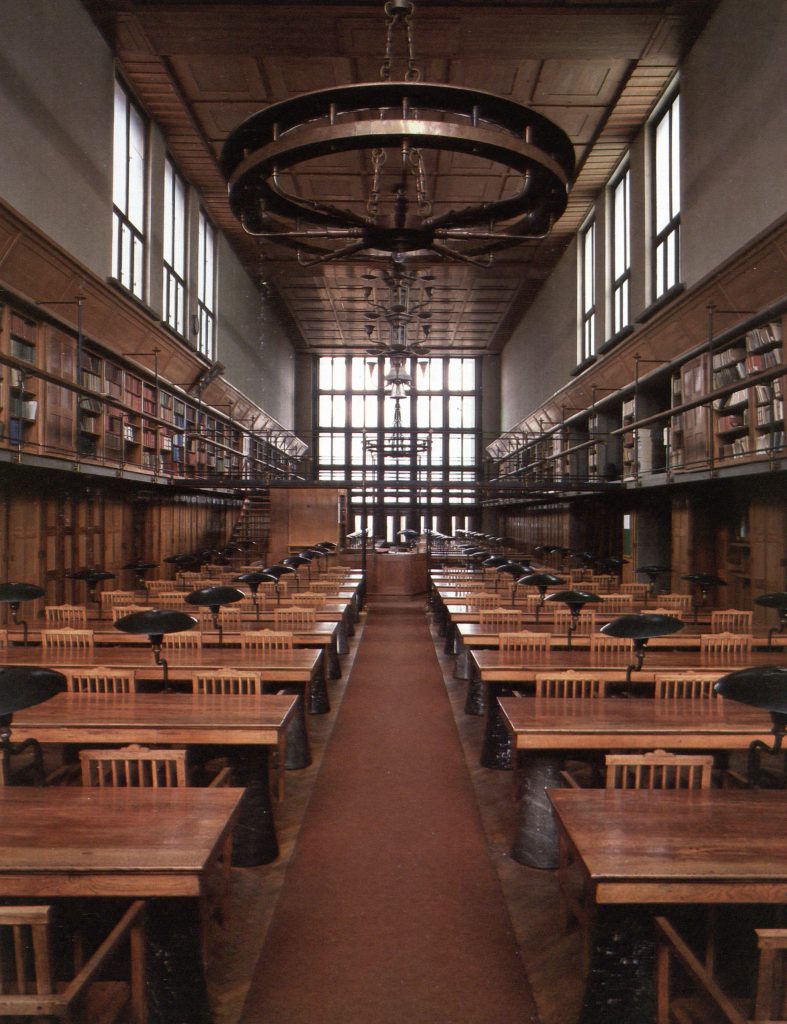

From this first proposal, Plecnik will evolve to the last and definitive, built today and which we are going to revisit. The plant, as in the first project, is a cube with cortile, crossed to the height of the first floor, by a volume that contains the communication core between the plant entrance down, and the Reading Room on that first floor. The building now has a long and uninterrupted traffic stairway ascent. The scheme is clearer, as we give up Plecnik to the unfolding of the staircase, so that the library paper over university faculty paper. The introduction of such a long uninterrupted transit is something in which would be worth stopping. If we examine libraries in the 19th century and even earlier, we will not find in any case, neither such a tangential location of the Reading Room nor a such ceremonious access. And at the same time it has to be said that, by placing in that remote or tangential position, at the end, the Reading Room, it is enhanced, enhanced, as a goal of this staircase.

Desde esta primera propuesta, Plecnik evolucionará a la última y definitiva, hoy construida y que vamos a revisitar. La planta, como en el primer proyecto, es un cubo con cortile, atravesado hasta la altura del primer piso, por un volumen que contiene el núcleo de comunicación entre la entrada en planta baja, y la Sala de Lectura en ese primer piso. El edificio tiene ahora un largo e ininterrumpido tránsito ascendente de escaleras. El esquema es más claro, al renunciar Plecnik al desdoblamiento de la escalera, de este modo, prima el papel de biblioteca sobre el de facultad universitaria. La introducción de tan largo tránsito ininterrumpido es algo en lo que valdría la pena detenerse. Si examinamos bibliotecas del siglo XIX e incluso anteriores, no encontraremos en ningún caso, ni una ubicación de la Sala de Lecturas tan tangencial ni un acceso tan ceremonioso. Y al mismo tiempo ha de decirse que, al colocar en esa posición alejada o tangencial, en el extremo, la Sala de Lecturas, queda ésta potenciada, realzada, como meta de esta escalera.

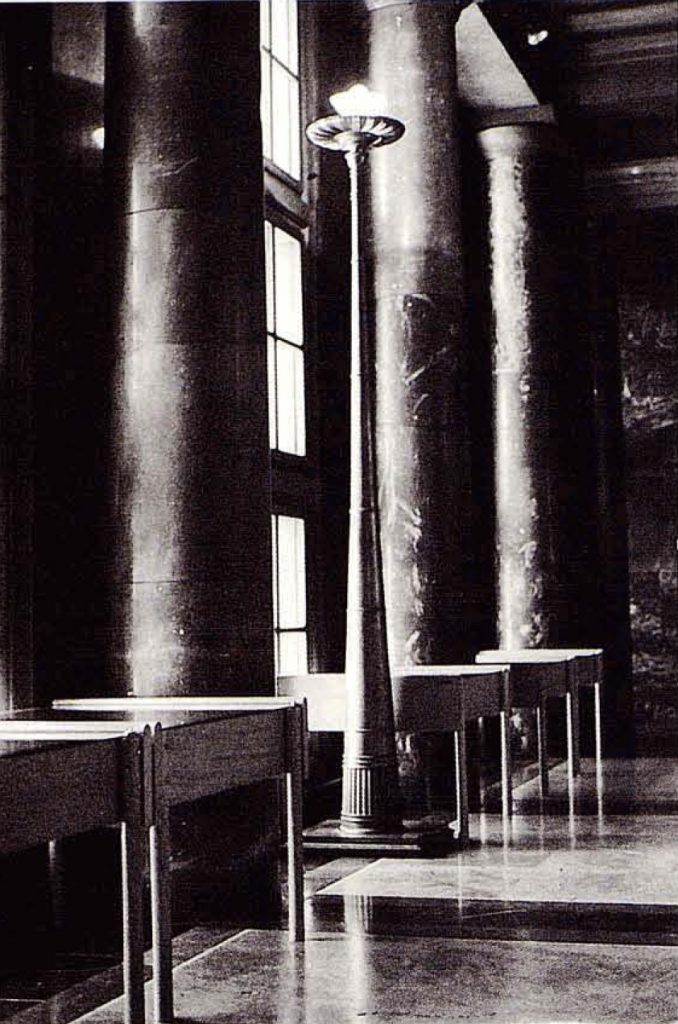

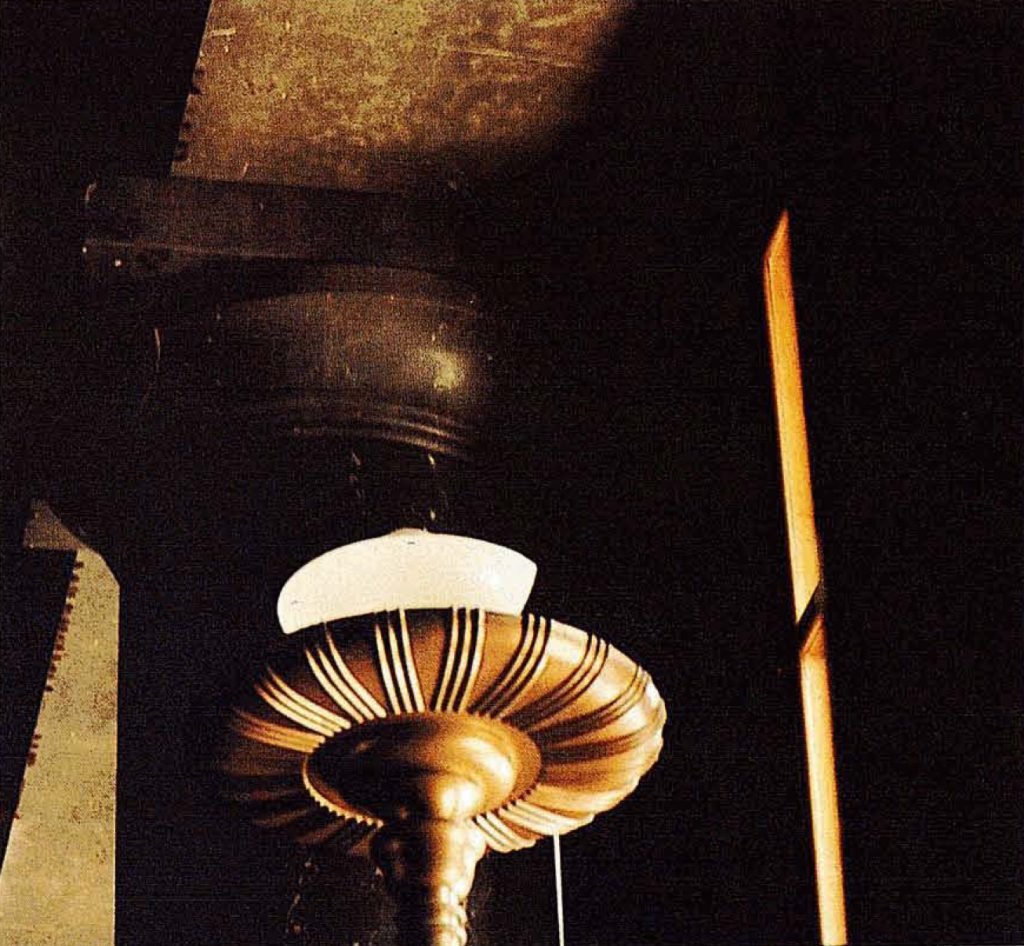

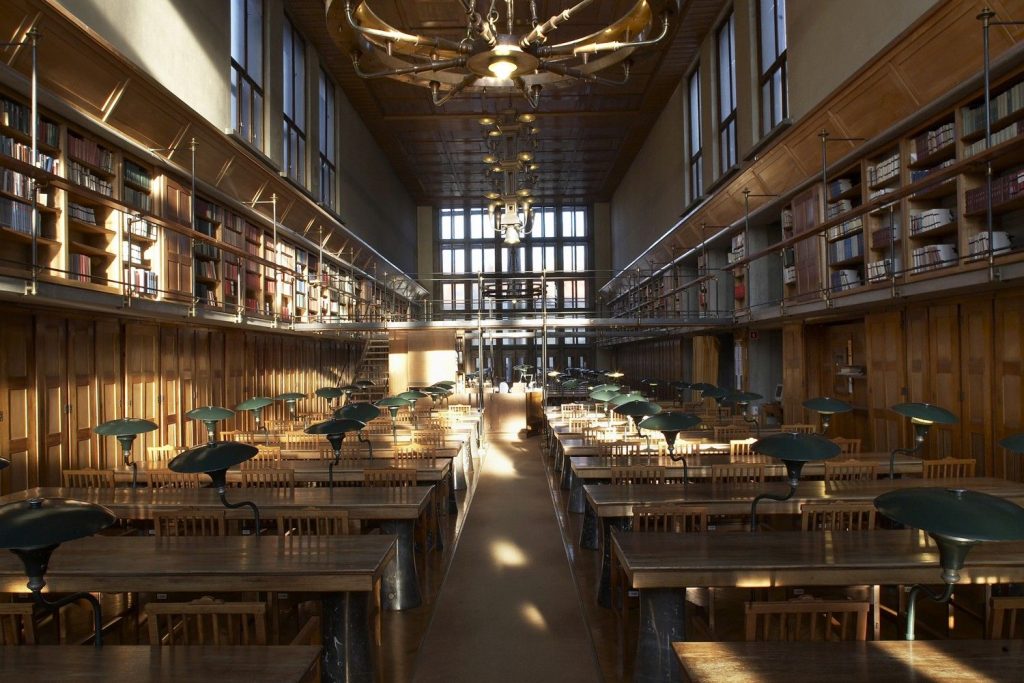

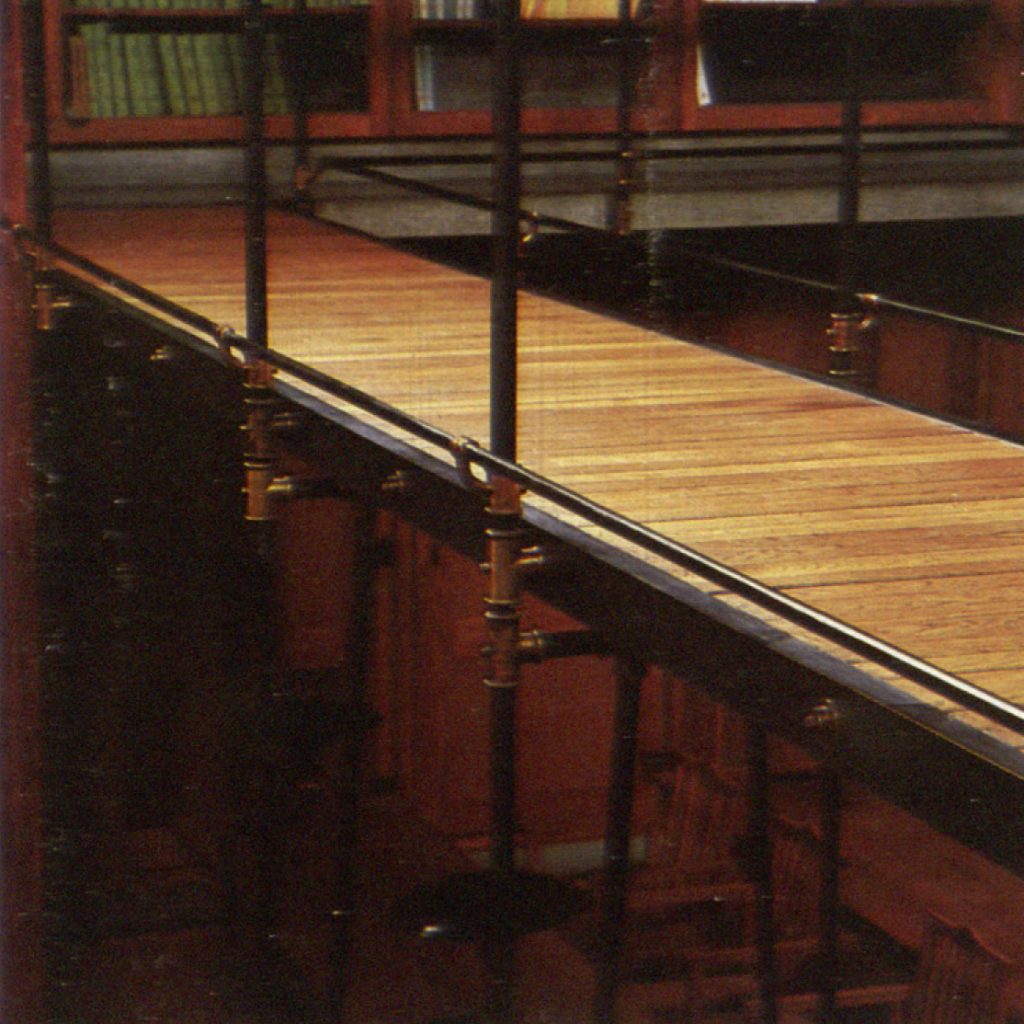

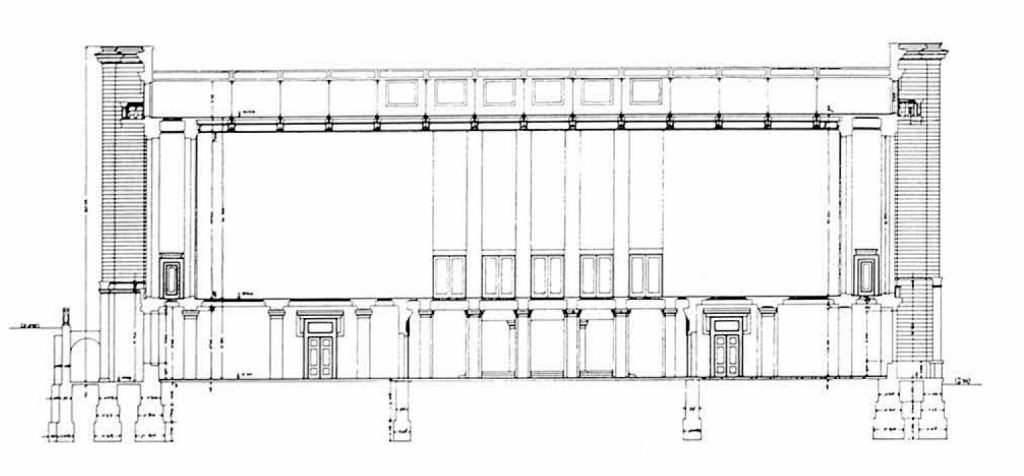

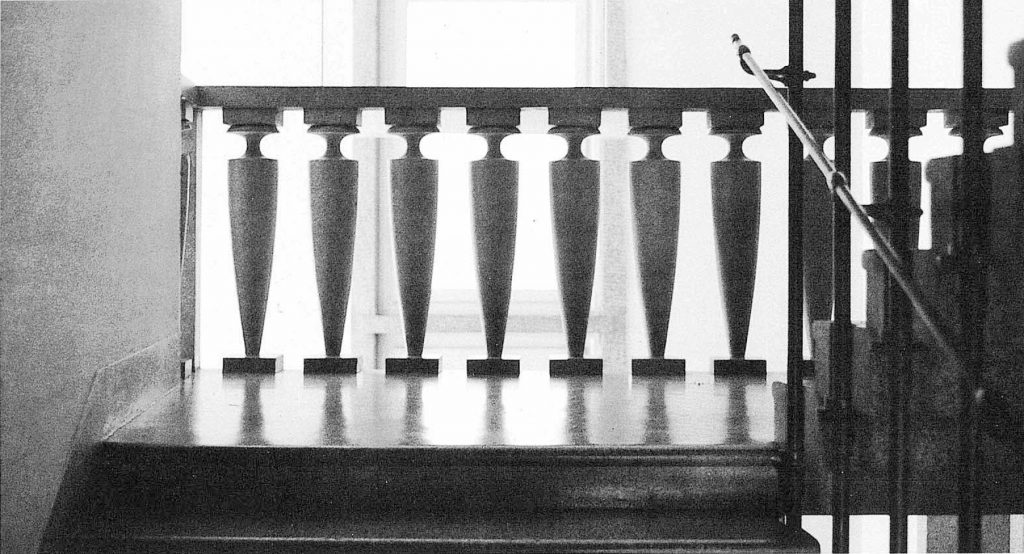

On the first (arrival) floor, a grid of columns fills the entire room. Four rows run in the same direction as the stairs: two are attached to the wall of the room, and the other two are placed on the walls that delimit the ascent of the stairs. When one ascends towards the Reading Room, one gradually perceives the great hypostyle room, which this antechamber to the Reading Room becomes. Having separated the columns from the wall, having continued the rows of columns once the staircase has reached the first floor, and having renounced introducing zenithal light, or a covering that is not flat, helps to enhance the hypostyle character of the room. One feels the ceremonial character of the staircase, in crescendo, as you reach this Hypostyle, and inevitably remember to the Scala Regia in the Vatican. There’s no doubt about it, as I pointed out earlier, the Reading Room, has been highlighted, in its tangential position, at the end of such a qualified journey. Plecnik seems to understand the world of sensations well, of perception, of the passage from darkness to light through of the routes and axes towards a focus of attention, of the contrasts, and ultimately the baroque theatricality.

On the first (arrival) floor, a grid of columns fills the entire room. Four rows run in the same direction as the stairs: two are attached to the wall of the room, and the other two are placed on the walls that delimit the ascent of the stairs. When one ascends towards the Reading Room, one gradually perceives the great hypostyle room, which this antechamber to the Reading Room becomes. Having separated the columns from the wall, having continued the rows of columns once the staircase has reached the first floor, and having renounced introducing zenithal light, or a covering that is not flat, helps to enhance the hypostyle character of the room. One feels the ceremonial character of the staircase, in crescendo, as you reach this Hypostyle, and inevitably remember to the Scala Regia in the Vatican. There’s no doubt about it, as I pointed out earlier, the Reading Room, has been highlighted, in its tangential position, at the end of such a qualified journey. Plecnik seems to understand the world of sensations well, of perception, of the passage from darkness to light through of the routes and axes towards a focus of attention, of the contrasts, and ultimately the baroque theatricality.

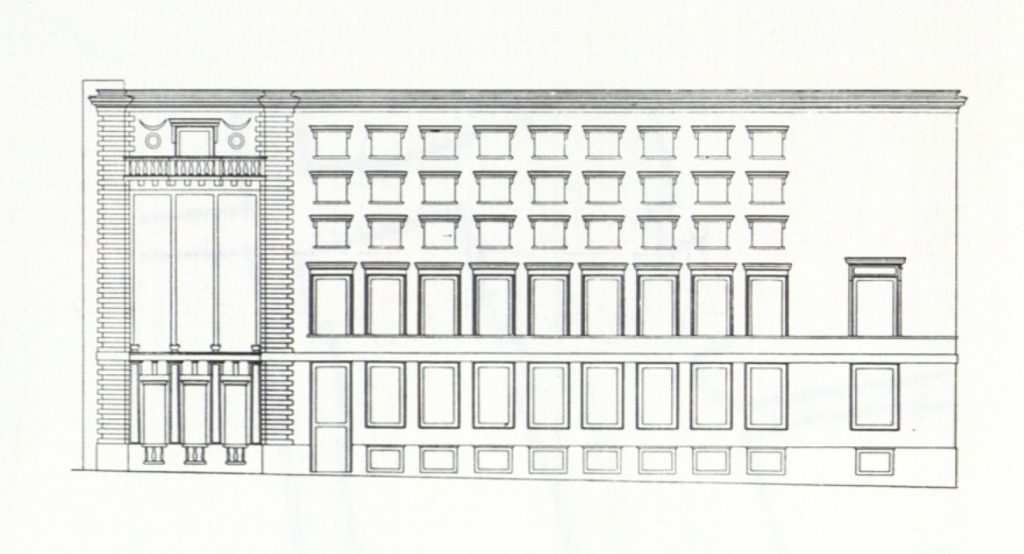

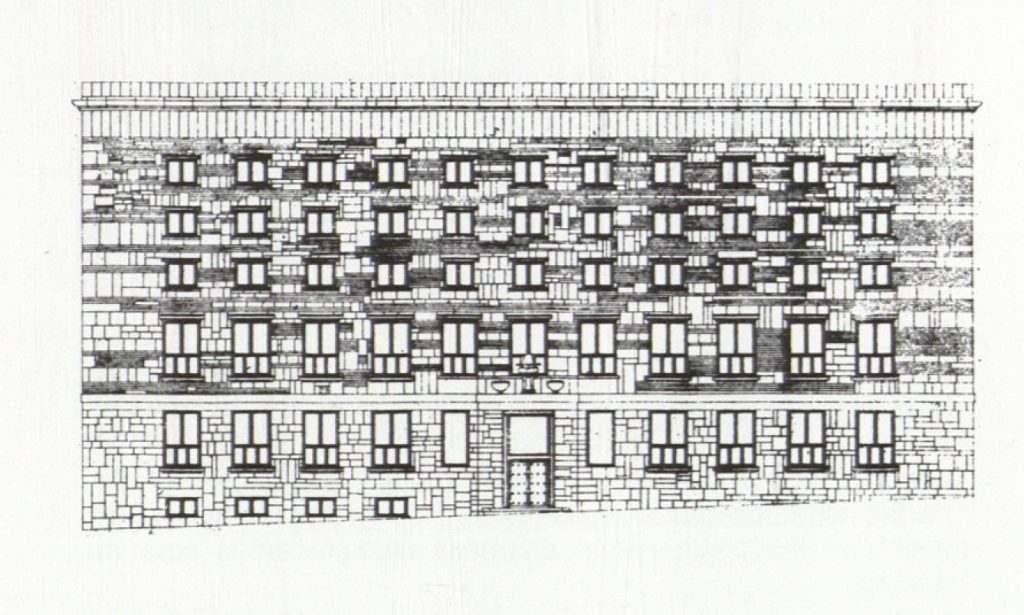

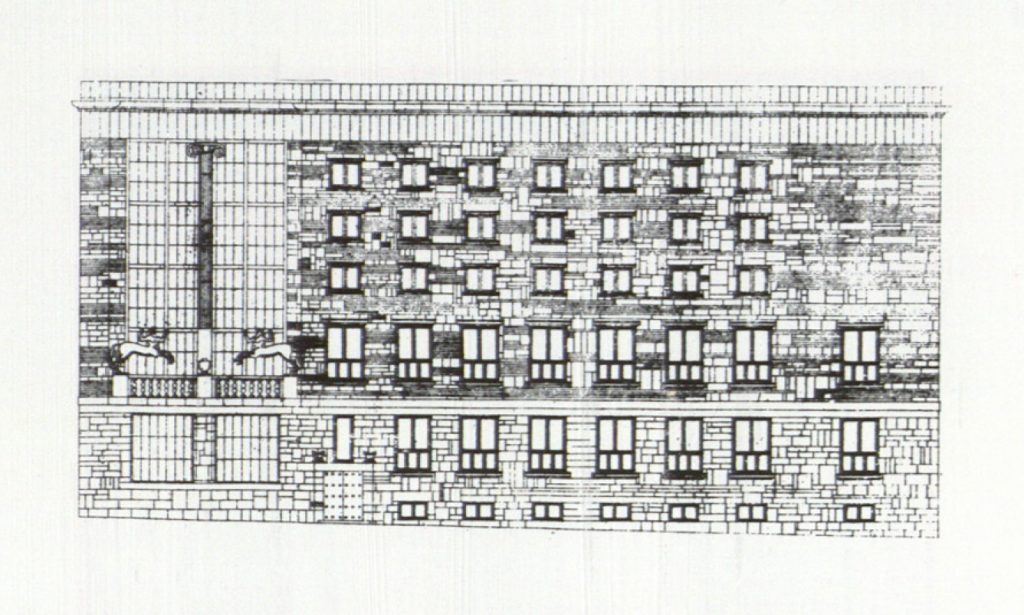

The casual arrangement of small mampos and other large, almost cyclopean, ones that stand out from the surface of stone and brick ashlars, produces a surprising effect of rustication. Rustication as a mannerist mechanism of force affection had already been used in Rome, at Porta Maggiore (s.l.a.C.) and then at Florentine palaces of the 14th century. It is not surprising that the impression produced by this building has been compared with that given by the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence. Furthermore, we cannot forget that the Mannerist architects of the Italian 500, so dear to Plecnik, were fond of the use of rusticato and rich and surprising textures. This treatment of the wall, existed in the popular architecture in the Karst region of Slovenia, where his father, and that Plecnik knew very well since he was a child. So, as well as suggesting to those of us who did not know the latter data, the rusticados of the past, this new aspect of the recovery of traditional architecture.

La disposición casual de pequeños mampuestos y otros grandes, casi ciclopeos, que resaltan de la superficie de sillares de piedra y ladrillo, produce un efecto sorprendente de rusticación. La rusticación como mecanismo manierista de afecto de fuerza se había utilizado ya en Roma, en la Porta Maggiore (s.l.d.C.) y luego en los palacios florentinos del Cuatrocientos. No puede sorprendernos que se haya comparado la impresión que produce este edificio con la que nos da el Palacio Medici Riccardi de Florencia. Además, no podemos olvidar, que los arquitectos manieristas del 500 italiano, tan queridos por Plecnik eran aficionados al uso del rusticato y a las texturas ricas y sorprendentes. Este tratamiento de la pared, existía en la arquitectura popular de la región del Karst, en Eslovenia, de donde era natural su padre, y que Plecnik conocía muy bien desde niño. Así que, además de sugerirnos, a quienes no supiéramos este último dato, los rusticados del pasado, aparece este nuevo aspecto de la recuperación de la arquitectura tradicional.

Text by Javier Cenicacelaya

VIA:

Revista Arquitectura COAM n°280, 1989

Quaderns