Image on the cover by Diana Lanciotti

INTERVIEW IN ENGLISH (Entrevista en español más abajo)

ARQUITECTURA-G: You come from a family of entrepreneurs and winemakers, and you contributed successfully to the winemaking industry with your packaging designs before you graduated from college. That was before your passion for domes drove you in another direction. You’ve mentioned the Pantheon and Santa Maria del Fiore several times as a reference, and we’ve read that even your thesis work during your architecture studies was about domes. How and when did you become interested in domes?

Dante Bini: Well, it was not only the influence of classic architecture. Back in the ‘60s, it was very fashionable to work with ancient structures like domes or tensile structures— in general, efficient structures that use little material. Traditional domes are built using very complicated formwork underneath, with an enormous carpentry effort and very complex scheduling. I realised that the cost of the formwork, a structure that disappears after the dome is completed, was sometimes higher than the cost of the dome itself. I started wondering how I could solve this problem and studied the work of Eduardo Torroja, Félix Candela, and other architects and engineers.

Besides the cost issue, I also decided to focus on the problem of scheduling. Building domes used to take lots of time. In 1961 I was finally granted my degree in architecture, and I decided to start working on my own. It wasn’t that easy to find clients, so I started a construction company with a friend of mine. I wanted to be an architect of my time, and I was thinking about thin-shell domes and vaults. One day, something extraordinary happened. I was playing tennis at a club in Bologna. It was winter and the weather was bad, and a large green-and-white balloon, inflated at low pressure, was set up to cover the playing courts. It was an inflatable roof. The match was intense and long, and at the end of the game we were unable to get out through the door, since in those few hours the area had been covered by a thick layer of snow. Finally we were able to get out by shovelling, and I wondered why we hadn’t noticed the increased pressure inside the balloon caused by the heavy mass of snow that had accumulated on the outer skin. I did a quick calculation of the approximate weight of the snow on the surface, and I realised that inflated even at low pressure the structure was able to support tons of weight! The entire weight of the reinforced-concrete dome I had designed for my university thesis could have been lifted with not much more pressure. At that moment it was very clear to me that a system based on that principle could allow a revolution in building vaults and domes in a cheap and rapid way; an inflatable formwork! I started with the first prototypes of what I called binishells, improving the system each time. The basic principle is to pour concrete over a circular membrane, where the reinforcing steel has already been placed. Then the membrane is inflated with a blower until it reaches the desired height, keeping the air pressure constant until the concrete sets hard enough. When that happens you stop the blower

(…)

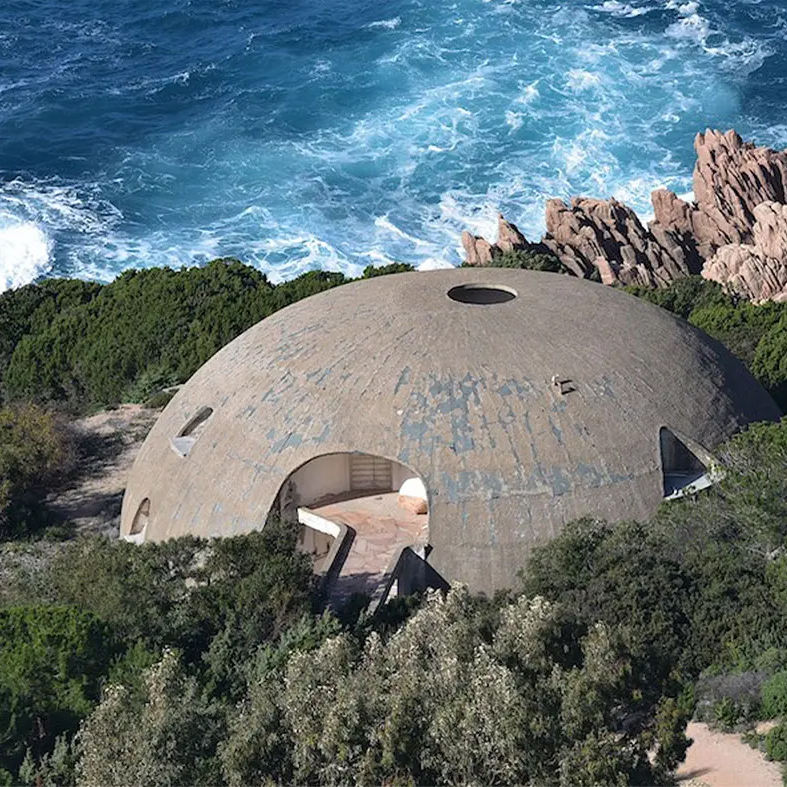

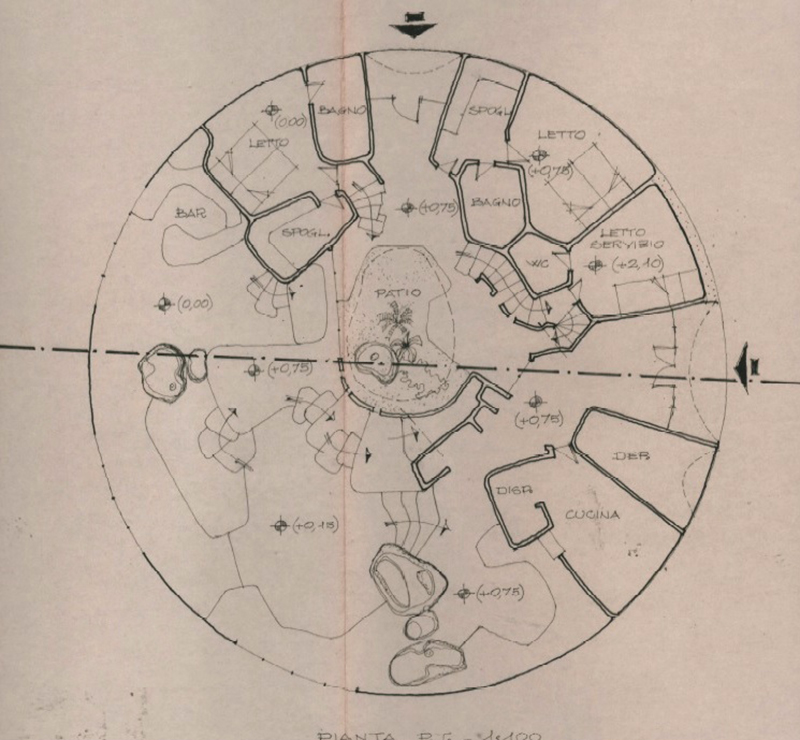

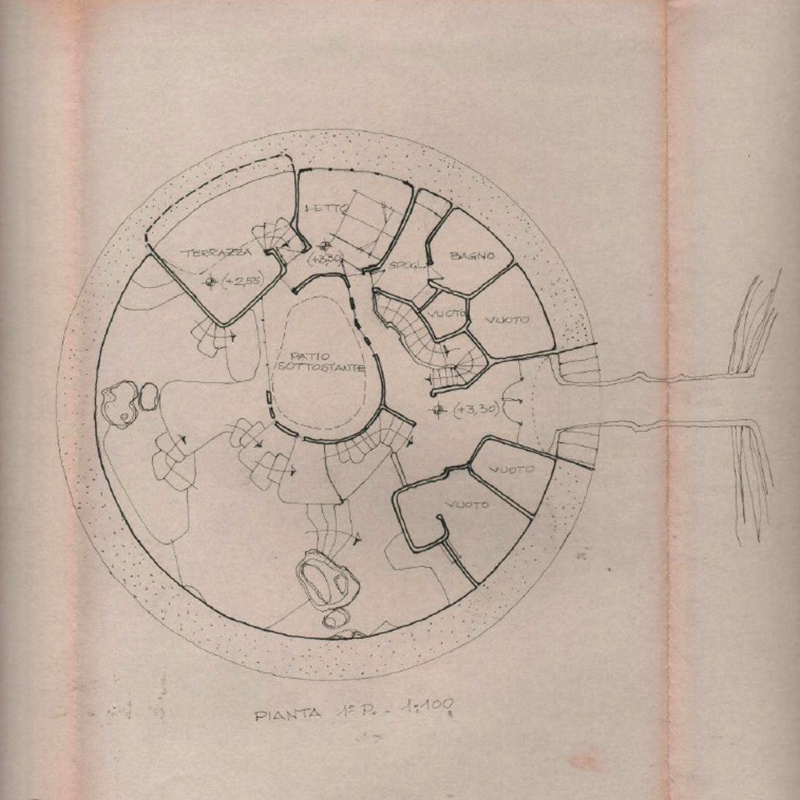

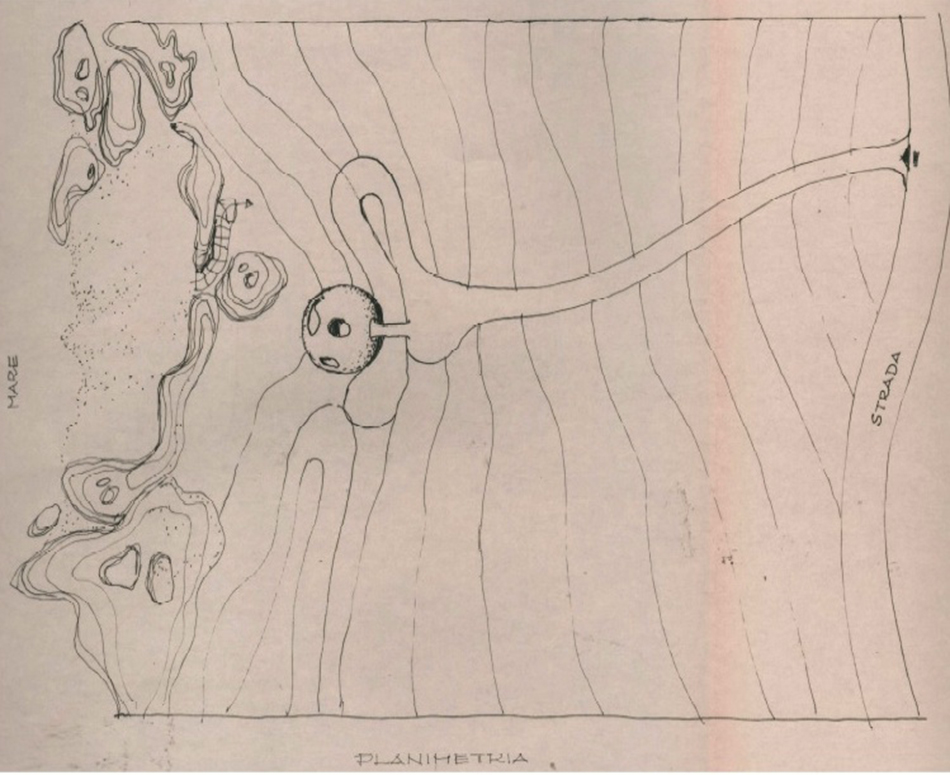

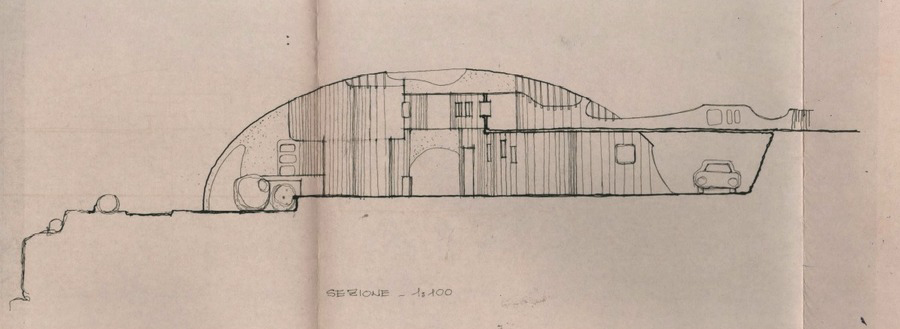

ARQUITECTURA-G: We are very interested in the formal particularities of the villa. Once you have the exterior shell, which is the starting point, you have a perfect and disciplined shape. The interior layout could follow the geometric purity or a more organic approach, which is what you chose. For example, there are no corners or right angles anywhere. We see that Mr Antonioni encouraged you to be free in forms, but we see as well that, back then, there was a tendency to imagine the future with organic interiors, such as the House of the Future, by the Smithsons. We also see references to a number of primitive tribal huts from around the world, from Laponia to Mongolia or Africa, which use lightweight materials and circular domes. A kind of primitive future.

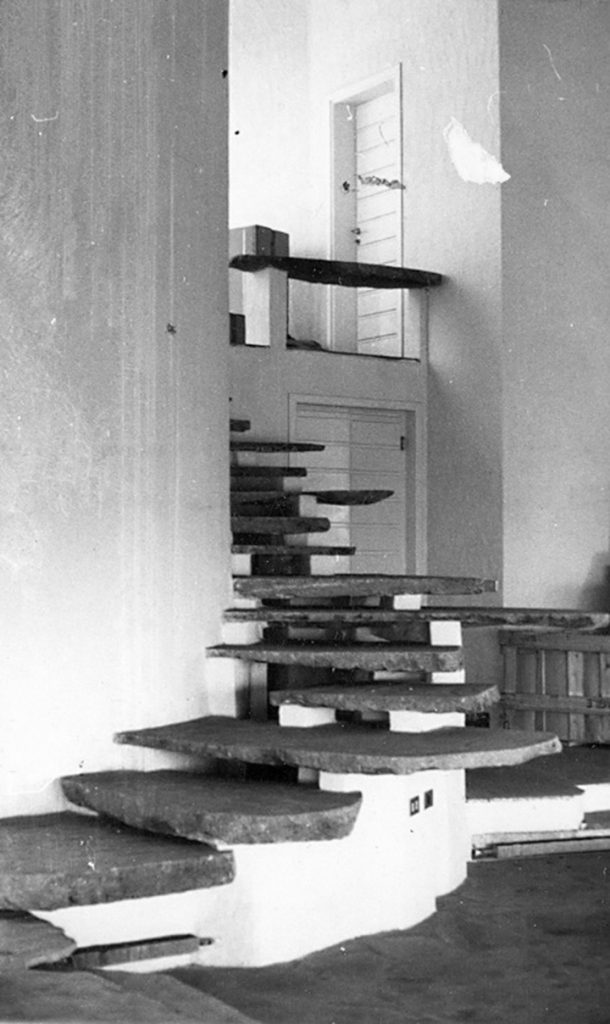

Dante Bini: The interior of this house is totally organic, there are no straight lines, unless you count the vertical partition walls. There might be something of that trend you mention, but, above all, it was about Antonioni’s intentions and goals. He wanted a house with nothing hanging on the walls, with only a few white pieces of furniture. The house is arranged on two levels, with access through the top part of the house. You enter through a suspended bridge with a free shape. Once you’re inside, you can see the huge space of the living room, which is double height, and views of the open sea. The bridge goes from the main entrance to the entrance of Antonioni’s room. From Antonioni’s bedroom, you could go to a terrace, and you can go from the entrance to a little internal bridge. The garden at the core had exactly the same shape as the hole I mentioned before. Antonioni said all the time, ‘I don’t want to cross a room and see the same volume all the time, again and again and again, when I’m walking through’. He said that when you go to a garden or a park, you walk through and the environment is moving around you, it’s not stable, it’s not static—it is dynamic. That is what he wanted. We talked a lot about that before the first drawings and the first model had been made.

Extract of the interview to Dante Bini by the Architectura G | You can read the full interview here

ENTREVISTA EN ESPAÑOL

ARQUITECTURA-G: Usted viene de una familia de emprendedores y enólogos, y contribuyó exitosamente a la industria del vino con su diseño para empacar botellas antes de comenzar la universidad, y antes de su pasión por las cúpulas que le llevaría en otra dirección. Ha mencionado el Panteón y Santa Maria del Fiore varias veces como referencia, y hemos leído que incluso tu trabajo de tesis durante tus estudios de arquitectura trataba sobre cúpulas. ¿Cómo y cuándo se interesó por las cúpulas?

Dante Bini: Bueno, no fue únicamente la influencia de la arquitectura clásica. Allá por los años 60, estaba muy de moda trabajar con estructuras antiguas como cúpulas o estructuras tensadas, en general, estructuras eficientes que utilizaban muy poco material. Las cúpulas tradicionales se construyen con un encofrado muy complicado, un enorme esfuerzo de carpintería y una compleja programación. Me di cuenta de que el costo del encofrado, una estructura que desaparece después de que se completa la cúpula, a veces era más alto que el csto de la cúpula en sí. Empecé a preguntarme cómo podría solucionar este problema y estudié el trabajo de Eduardo Torroja, Félix Candela entre otros arquitectos e ingenieros.

Además del tema de los costos, también decidí centrarme en el problema del calendario. La construcción de cúpulas solía llevar mucho tiempo. En 1961 finalmente me gradué en arquitectura y decidí empezar a trabajar por mi cuenta. No fue tan fácil encontrar clientes, así que inicié una empresa de construcción con un amigo mío. Quería ser un arquitecto de mi tiempo y estaba pensando en bóvedas con un delgado espesor. Un día sucedió algo extraordinario. Estaba jugando al tenis en un club de Bolonia. Era inviern, hacía mal tiempo por lo que se instaló una gran estructura hinchable verde y blanca, inflado a baja presión, para cubrir las pistas de juego. Era un techo inflable. El partido fue intenso y largo, y al final no podíamos salir por la puerta, ya que en esas pocas horas la zona había quedado cubierta por una gruesa capa de nieve. Finalmente pudimos salir quitando la nieve, y me pregunté por qué no habíamos notado el aumento de presión dentro del globo causado por la gran masa de nieve que se había acumulado en la piel exterior. Hice un cálculo rápido del peso aproximado de la nieve en la superficie y me di cuenta de que inflada incluso a baja presión, ¡la estructura podía soportar toneladas de peso! Todo el peso de la cúpula de hormigón armado que había diseñado para mi tesis universitaria podría haberse levantado sin mucha más presión. En ese momento me quedó muy claro que un sistema basado en ese principio podría permitir una revolución en la construcción de bóvedas y cúpulas de forma barata y rápida; un encofrado inflable! Empecé con los primeros prototipos de lo que llamé binishells, y mejoré el sistema en cada ocasión. El principio básico es verter el hormigón sobre una membrana circular, donde ya se ha colocado el acero de refuerzo. Luego, la membrana se infla con un soplador hasta que alcanza la altura deseada, manteniendo constante la presión del aire hasta que el concreto se endurece lo suficiente. Cuando eso sucede, detienes el inflador.

(…)

ARQUITECTURA-G: Estamos muy interesados en las particularidades formales de la villa. Una vez que situada la cúpula exterior como punto de partida con una forma perfecta y disciplinada, la organización interior podría haber continuado con esa pureza geométrica o con un enfoque más orgánico, que es lo que eligió finalmente. Antonioi le animó a ser libre en las formas pero también vemos que durante aquella época había una tendencia a imaginar el futuro con interiores orgánicos, tales omo la Casa del Futuro, de los Smithson. También vemos referencias a una serie de chozas tribales primitivas de todo el mundo, desde Laponia hasta Mongolia o África, que utilizan materiales ligeros y cúpulas circulares. Una especie de futuro primitivo.

Dante Bini: El interior de esta casa es totalmente orgánico, no hay líneas rectas, a menos que se cuenten los tabiques verticales. Puede que hubiera algo de esa tendencia que mencionas pero principalmente se trataba de las intenciones y los deseos de Antonioni: él quería una casa sin nada colgado de las paredes y únicamente unos pocos muebles blancos. La vivienda se distribuye en dos niveles con acceso desde su planta superior. Se entran por un puente cogante de forma libre. Una vez ddentro, se puede ver el enorme espacio del salón que tiene doble altura y vistas hacia el mar. El puente va desde la entrada principal hasta la habitación de Antonioni. Desde el dormitorio de Antonioni puedes ir a una terraza y a la entrada a través de un pequeño puente interior. El jardín central tenía exactamente la misma forma que la apertura que mencioné anteriormente. Antonioni decía todo el tiempo: “No quiero cruzar una habitación y ver siempre el mismo volumen, una y otra y otra vez, cuando estoy caminando”. Decía que cuando vas a un jardín o a un parque, caminas y el entorno se mueve a tu alrededor, no es estable, no es estático, es dinámico. Eso es lo que quería. Hablamos mucho de eso antes de que se hicieran los primeros dibujos y la primera maqueta.

Extracto de la entrevista a Dante Bini por parte de Architectura G | Puedes leer la entrevista completa en inglés en el siguiente link