*** Article written by Alexandrina Marinova ***

Plovdiv. The second largest city in Bulgaria and one of the oldest in Europe. Among the 7 hills (tepe) encompassed by its territory, there are numerous witnesses of its incessant life: archaeological finds of Thracians, Greeks, Romans, Slavs, Bulgarians and Ottomans. However, where you can best appreciate the multiple layers of its rich history is in the Old City.

Plovdiv. La segunda ciudad más grande de Bulgaria y una de las más antiguas de Europa. Entre las 7 colinas (tepe) por las que se expande su territorio, se encuentran numerosos testigos de su vida incesante: hallazgos arqueológicos de tracios, griegos, romanos, eslavos, búlgaros y otomanos. Sin embargo, donde mejor pueden apreciarse las múltiples capas de su rica historia es en la Ciudad Antigua.

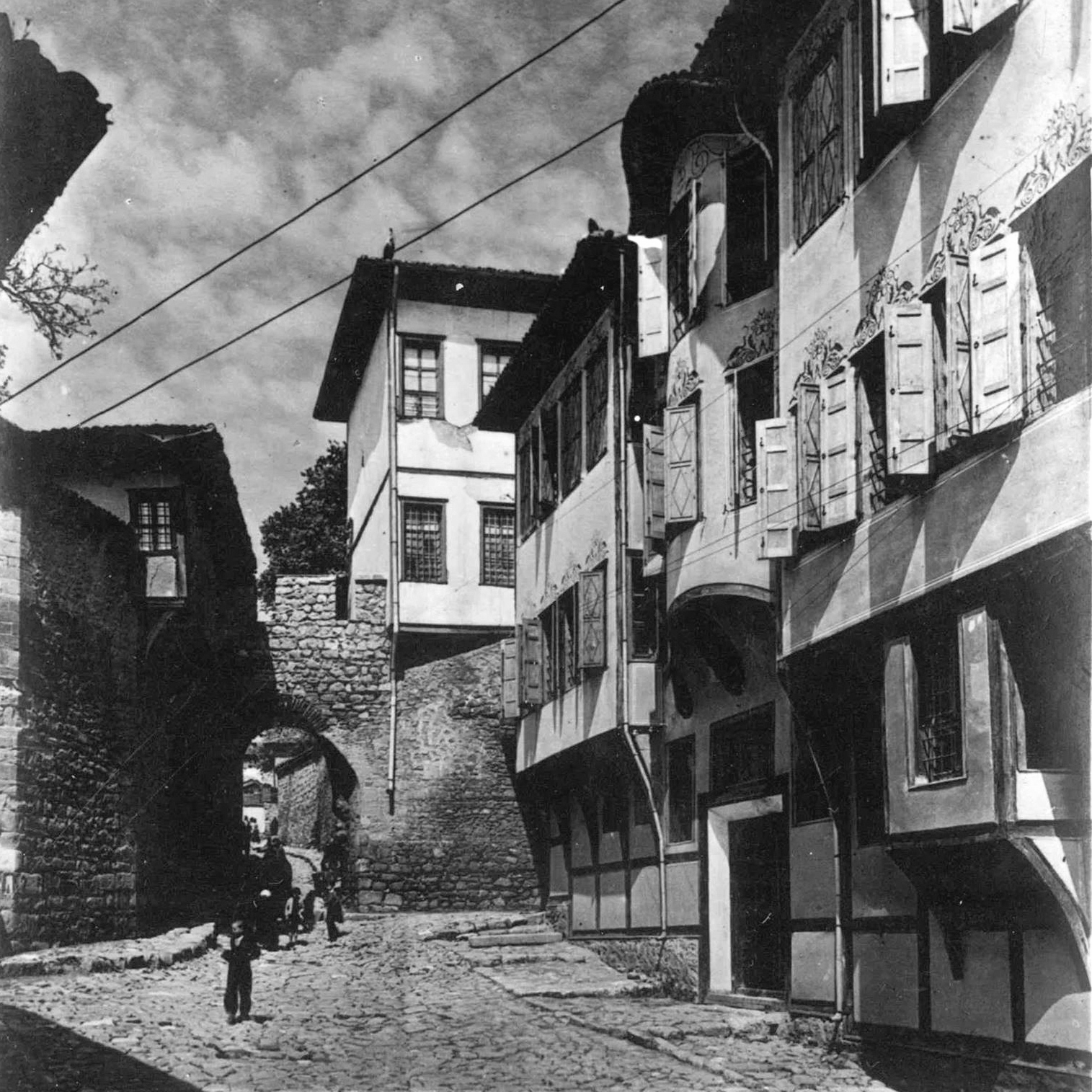

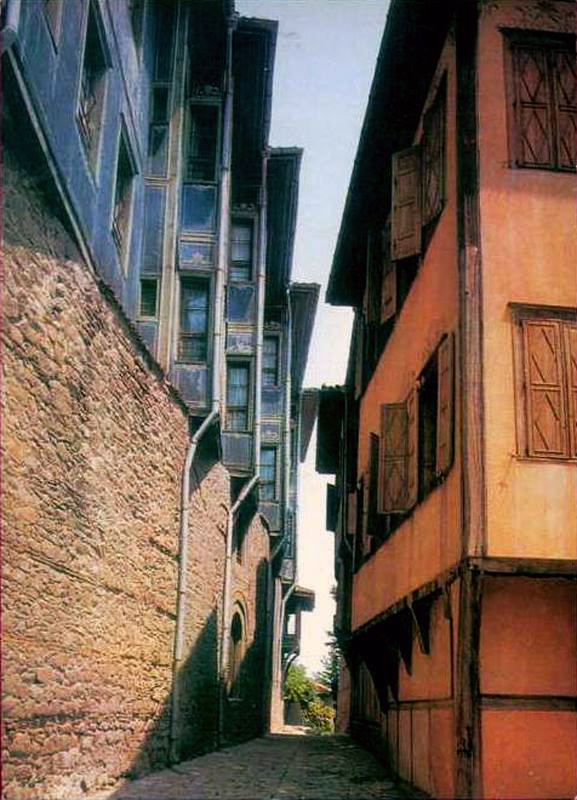

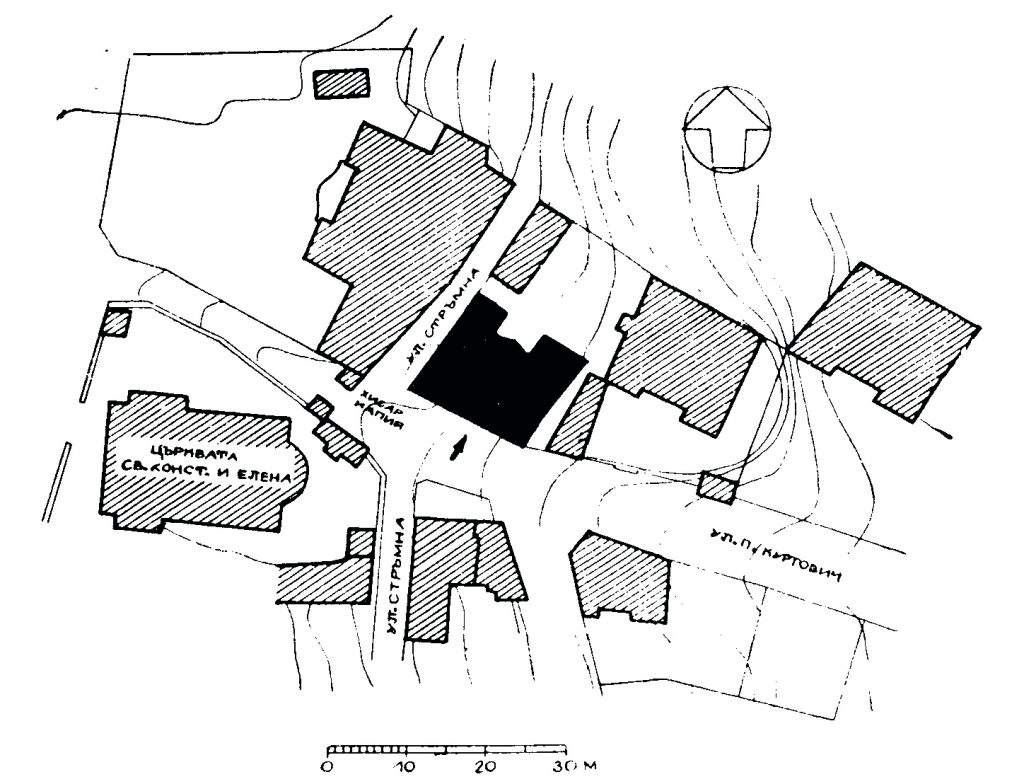

We enter into the Old City, leaving on our left-hand side the ruins of the East Gate of Philippopol (Roman name of Plovdiv), and continue uphill on the street “Tsanko Lavrenov”, surrounded by traditional houses and the remains of a Roman tower and a fortress. Arriving at Hisar Kapia, one of the three medieval city gates, on the right side, just on the corner with street “Strumna”, rises one of the most spectacular houses in the historic center, the Georgiadi house.

Entramos al recinto de la Ciudad Antigua, dejando a la izquierda las ruinas de la Puerta Este de Filipopol (nombre romano de Plovdiv), y subimos por la calle “Tsanko Lavrenov”, ladeada por casas tradicionales y restos de una torre y muralla romanas. Llegando a Hisar Kapia, una de las tres puertas medievaels de la ciudad, a la derecha, en el cruce con calle “Strumna”, se eleva una de las casas más espectaculares del casco histórico, la casa Georgiadi.

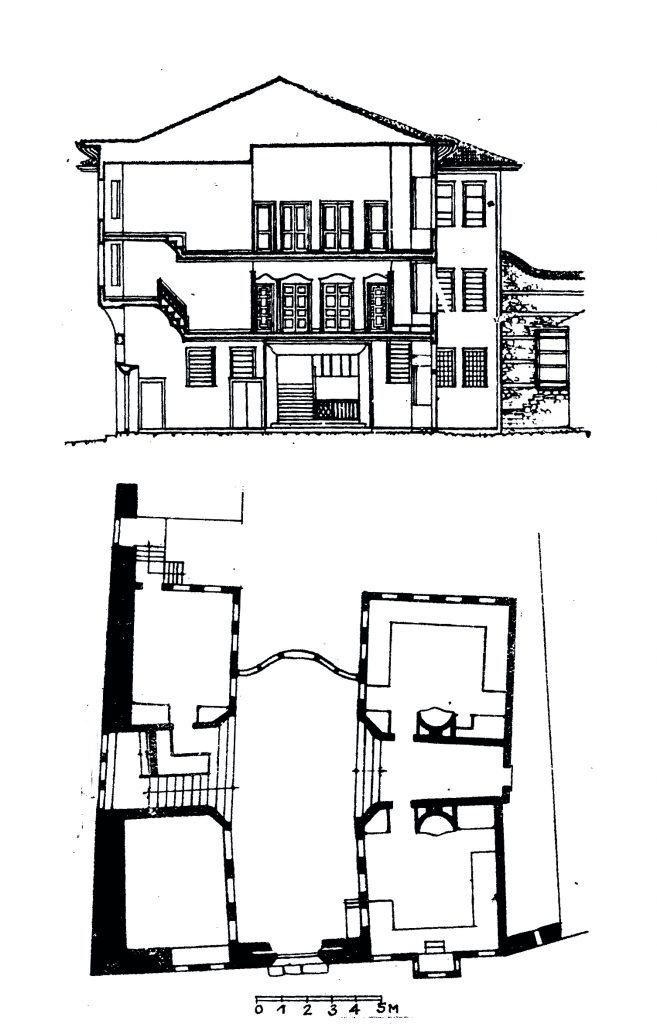

Built in the middle of the 19th century, by one of the most outstanding builders of that time, Hadzi Georgi Georgiev Hadziyski, the house is representative of the typical symmetrical houses of Plovdiv and the typology of the sarayhouses, or mansions. Commissioned by Georgi Kendindenoglu, shortly after being finished, it was given as a dowry on his daughter Elena’s wedding with the wealthy merchant of Thessaloniki, Dimitar Georgiadi, whose last name the house owes its name to.

Construida a mediados del siglo XIX, por uno de los constructores más destacados de la época, hadzi Gueorgui Gueorguiev Hadziyski, la casa es representante de las típicas casas simétricas de Plovdiv y de la tipología de las casas saray, o palacetes. Encargada por Gueorgui Kendindenoglu, al poco de ser acabada fue regalada como dote para la boda de su hija Elena con el rico comerciante de Tesalónica, Dimitar Gueorguiadi, a cuyo apellido debe su nombre la casa.

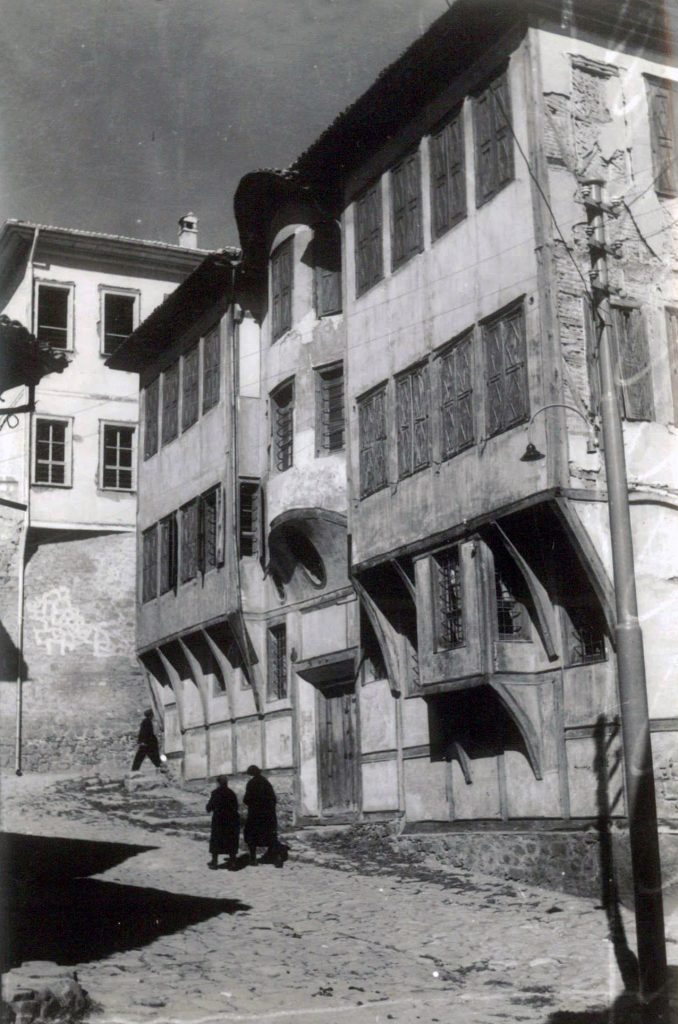

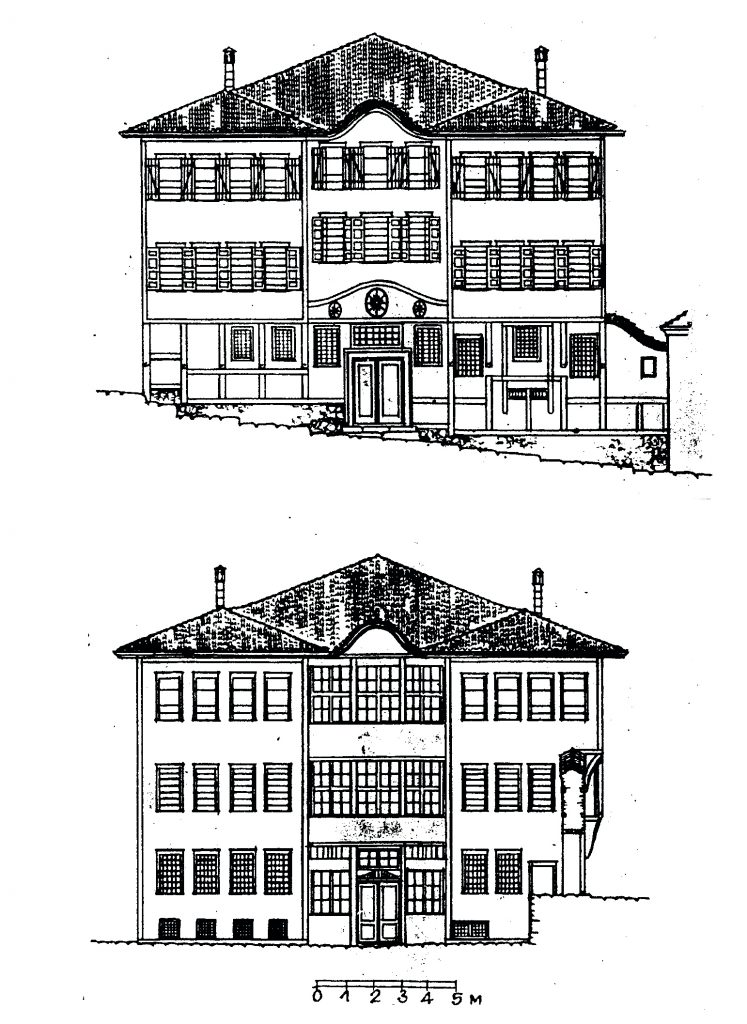

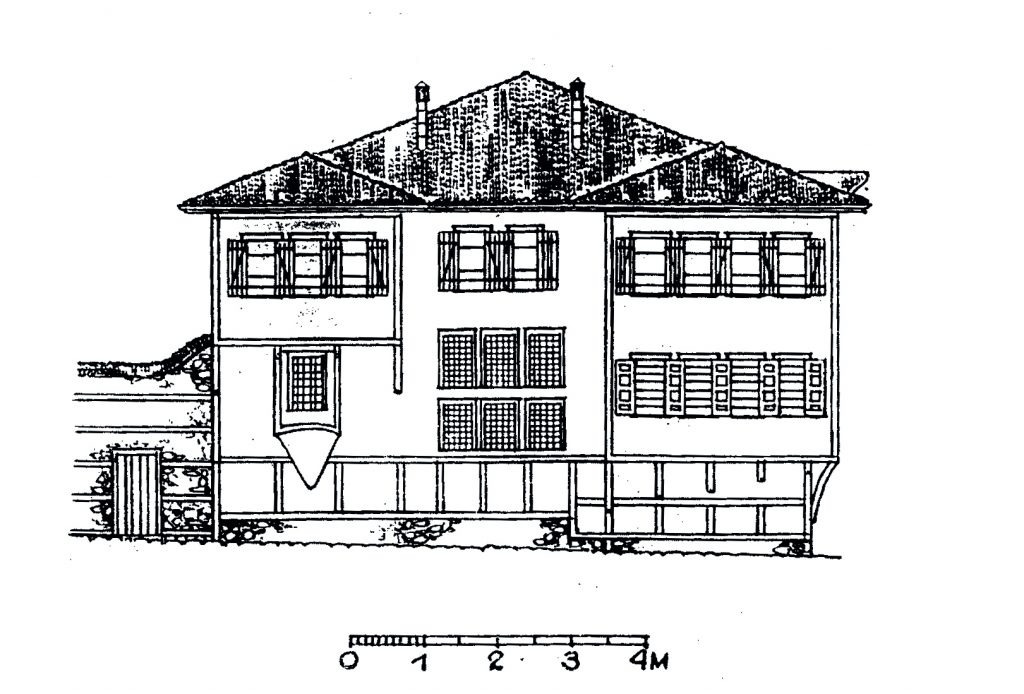

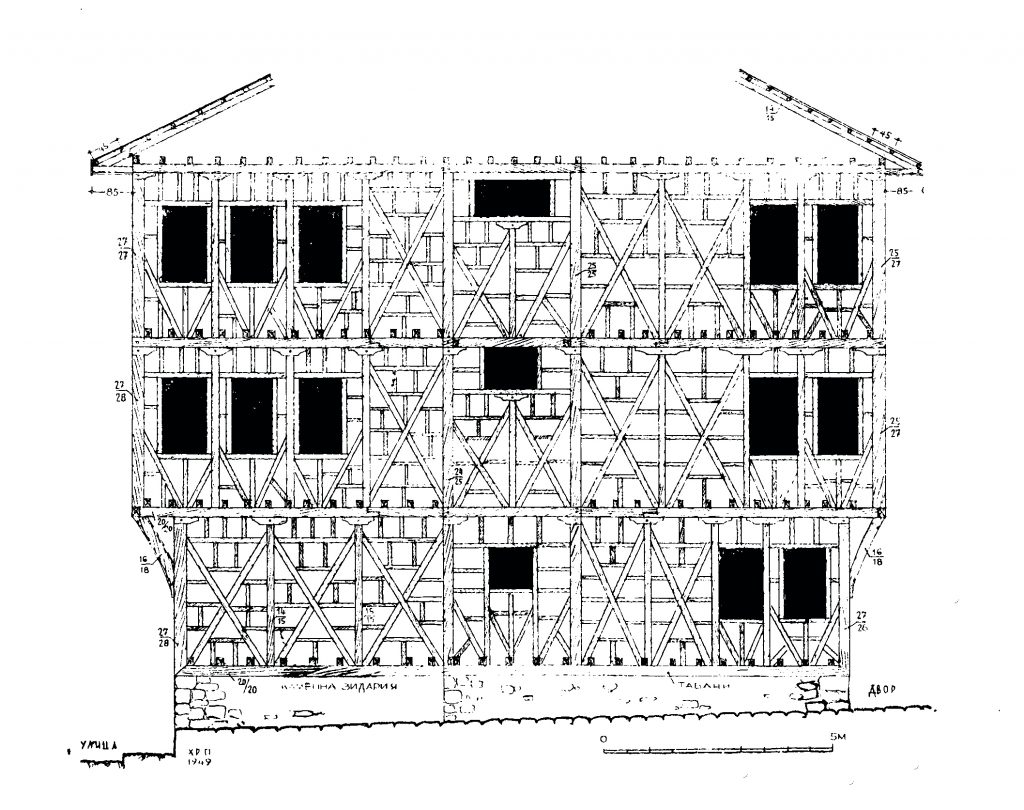

Seen from the street, the building impresses with a great height: it has a cellar, ground floor and two more floors. The base is made of thick stone walls, from which a wooden skeleton starts, filled with fine clay bricks.

Al verlo desde la calle, el edificio impacta con su gran altura: tiene una bodega, planta baja y dos plantas más. Su base es de gruesos muros de piedra, en los que se apoya un esqueleto de madera, relleno con ladrillos finos de arcilla.

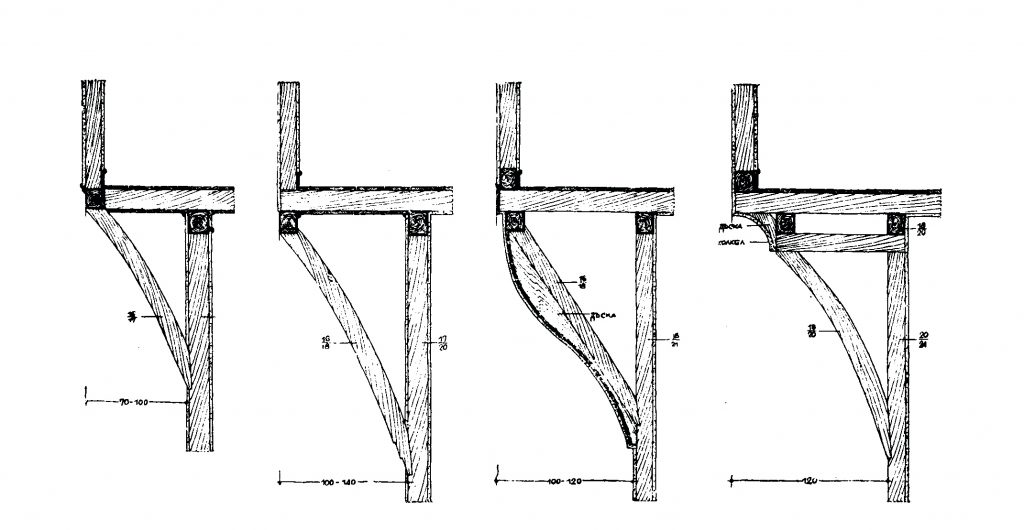

Occupying almost the entire space of its small plot, the silhouette of the ground floor follows the line of the street, while the upper storeys show over the street with oriels of varied morphologies. In addition to giving abundance and dynamics to the facades, those bay windows come from a purely functional need, since the plots of the old cities used to be very irregular (either to allow the passage of animals and cars or because of the topography), the ground floors had to respect their shape. However, in height the houses used to come a bit over the street, thus obtaining larger and more regular rooms. The remaining spaces were converted into service rooms. Also, the rectangular shape was needed to facilitate the elaboration of the geometric coffered ceilings.

Aprovechando casi la totalidad de la pequeña parcela, la silueta de la planta baja sigue la línea de la calle, mientras que las siguientes plantas se asoman en forma de voladizos de morfologías variadas. Además de dar una riqueza y dinámica a las fachadas, esos ensanchamientos en las plantas superiores vienen desde una necesidad puramente funcional, ya que las parcelas de las antiguas ciudades solían ser irregulares (sea para permitir el paso de los animales y los coches o por la topografía), las plantas bajas tenían que respetar su forma. Sin embargo, en altura las casas solían salirse encima de la calle, conseguiendo así estancias más grandes y regulares. Los espacios restantes se convertían en cuartos de servicio. Asímismo, la forma rectangular se buscaba para facilitar la elaboración de los artesonados geométricos que decoraban los techos.

In between the bays on the main façade, the central one stands out with its peculiar curved pediment, whose shape is also transferred in plan. This element is typical for the houses of the Bulgarian Renaissance and it is patent of the most famous and respected Bulgarian builder of the time, Maystor Kolyo Ficheto, to whom owes its name, “Fichevska kobilitza” (also called “baroque curve“). Kobilitza, is a curved wooden carrying pole used by women to carry water, an indispensable and exclusively feminine utensil, which had a very special place in the life of the Bulgarians. In addition to its primary function, it had a secondary one, serving as a weapon that its owners did not hesitate to use for self-defense. The pole had become so sacred that even took part in numerous rites, such as traditional wedding and many other folk rituals. Due to the shape similarity, people came to call many other curved silhouette things with the name “kobilitza” from hills, to the curved pediments of the traditional houses.

Entre los voladizos de la fachada principal, destaca el central, con su peculiar frontón curvado, cuya forma se traspasa también en planta. Dicho elemento es típico para las casas del Renacimiento búlgaro y es patente del constructor búlgaro más famoso y respetado de la época, maystor Kolyo Ficheto, a quien debe su nombre, “Fichevska kobilitza” ( también llamada “curva barroca”). Kobilitza, a su vez es una pieza de madera curvada con la que las mujeres llevaban dos recipientes de agua, un utensilio indispensable y exclusivamente femenino, que tenía un lugar muy especial en la vida de las búlgaras. Además de su función primaria, tenía otra secundaria, servía como arma que sus propietarias no dudaban en usar para autodefensa. Había llegado a sacralizarse hasta el punto de ser parte inseparable de numerosos ritos, como por ejemplo la boda tradicional u otros rituales folklóricos. Por el parecido de las formas, la gente llegó a llamar muchas otras cosas de silueta curva con el nombre “kobilitza” desde las colinas, hasta los frontones curvados de las casas tradicionales.

Entering to the house Georgiadi, you go into a large covered patio, paved with stone slabs, which gives continuity to the street inside the house and connects it with the garden. In addition to establishing a relationship between the two zones, public and private, this lobby perhaps served to shelter a car or animals inside the house as a garage.

Entrando por la puerta principal de la casa Gueorguiadi, se accede a un gran patio cubierto, pavimentado con losas de piedra, que da continuidad a la calle dentro de la casa, uniéndola además con el jardín. Además de establecer una relación entre las dos zonas, pública y privada, esté vestíbulo quizás servía para dar cobijo a un coche o animales dentro de la casa a modo de garaje.

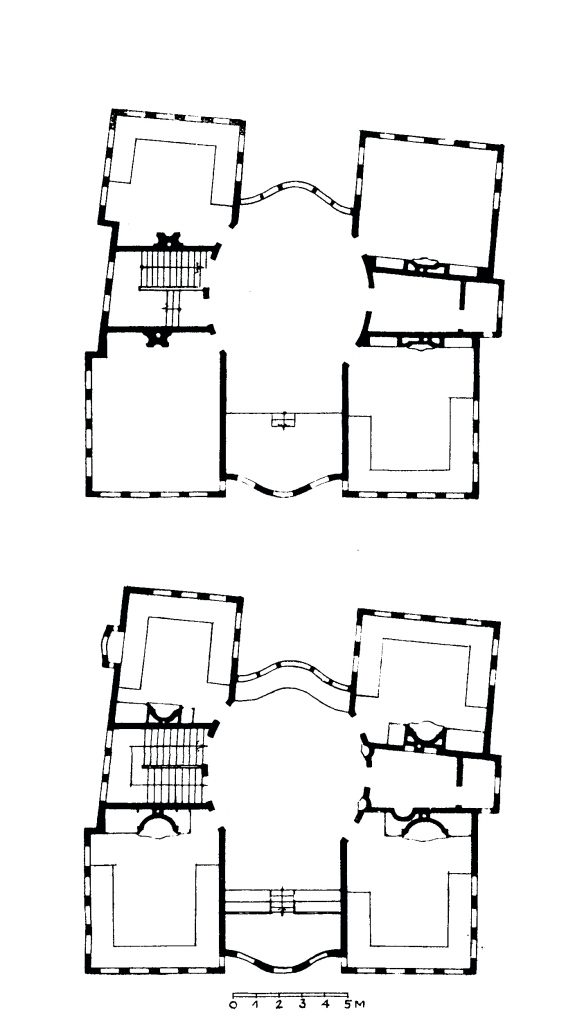

As we mentioned previously, the Georgiadi house is one of the best representative of the traditional symmetrical houses of Plovdiv, a principle that dominates not only in its facades, but is also part of the plan composition, organized with two axes of symmetry. Each floor has a large central space, surrounded by four rooms, among which are the staircase and the service rooms.

Como fue mencionado previamente, la casa Gueorguiadi es uno de los mejores representante de las tradicionales casas simétricas de Plovdiv, un principio que domina no solo en sus fachadas, sino forma parte de la composición de las plantas, organizadas a base de dos ejes de simetría. Cada planta cuenta con un gran espacio central, rodeado por cuatro estancias, entre las que están la escalera y los cuartos de servicio.

Going upstairs by the two-section staircase with a curious double curved wooden roof, we reach the first floor’s central hall. The space surprises with its dimensions, the elliptical shape, the richness of its soft pink wall decorations and the coffered ceilings of geometric ornamentations, in which center a stylized sun is usually represented, showing the virtuosity of the artisan and the well-being of the owners. We could separate that hall into three parts: the central ellipse, hayet, with the most representative function; to the right, facing the street, kyoshk, a raised platform with 4 steps, where an orchestra used to play during the parties, that took place in the house; to the left, the most daily area, facing the garden and flanked by ¨minderi¨ (sofas attached along the walls that could become beds in night). Separating the functions of the house according to its orientation, respectively towards the public or the private area, is evident in the pairs of rooms in each floor: the representative ones are oriented towards the street, being its decoration richer and less functional, while the rooms facing the garden, were for daily use, humbly decorated, but with many wardrobes and minderi.

Subiendo por la escalera de dos tramos con un curioso techo de madera de doble curvatura, llegamos al vestíbulo central de la primera planta. El espacio sorprende por sus dimensiones, su forma elíptica, la riqueza de sus decoraciones murales de suave color rosa y los artesonados de ornamentaciones geométricas, en cuyo centro suele está representado un sol estilizado, muestra del virtuosismo del artesano y del bienestar de los propietarios. Podríamos separar ese gran hall en tres partes: la elípse central, hayet, con la función más representativa; a la derecha, dando hacia la calle, kyoshk, una plataforma elevada con 4 peldaños, donde solía ponerse una orquesta en las numerosas fiestas que se celebraban en la casa; a la izquerda, la parte más cotidiana que da al jardín, ladeada por ¨minderi¨ (sofas adosados a lo largo de las paredes que de noche se convertían en camas). El gesto de separar las funciones de la casa según su orientación, respectivamente hacia la parte pública o la privada, se nota también en los pares de habitaciones en cada planta: las de uso más representativo dan hacía la calle, siendo su decoración más rica y menos funcional, mientras que los cuartos orientados hacia el jardín, eran de uso más cotidiano, de decoración más humilde, pero con numerosos armarios empotrados y minderi.

In front of the staircase on the first floor there is a marble sink, embedded in the wall, and next to it, between the two large rooms, a service area called cafe odaya, the coffee room. This is where the hot drink was prepared and served to the guests in the reception hall.

Enfrente de la escalera de la primera planta se encuentra un lavabo de mármol, empotrado en la pared, y a su lado, entre las dos habitaciones grandes, una zona de servicio llamada cafe odaya, el cuarto del café. Allí es donde se preparaba la bebida caliente y se llevaba a los invitados en el vestíbulo de recepciones.

The last floor repeats the distribution of the previous one, only its decorations were never finished. The smooth white walls, the high roof without coffered ceilings and the spacious rooms give the sensation of being in a bourgeois house from the next century.

Las última planta repite la distribución de la anterior, pero sus decoraciones nunca fueron acabadas. Las paredes lisas y blancas, los altos techos sin artesonados y las estancias espaciosas dan la sensación de encontrarse en una vivienda burguesa del siglo siguiente.

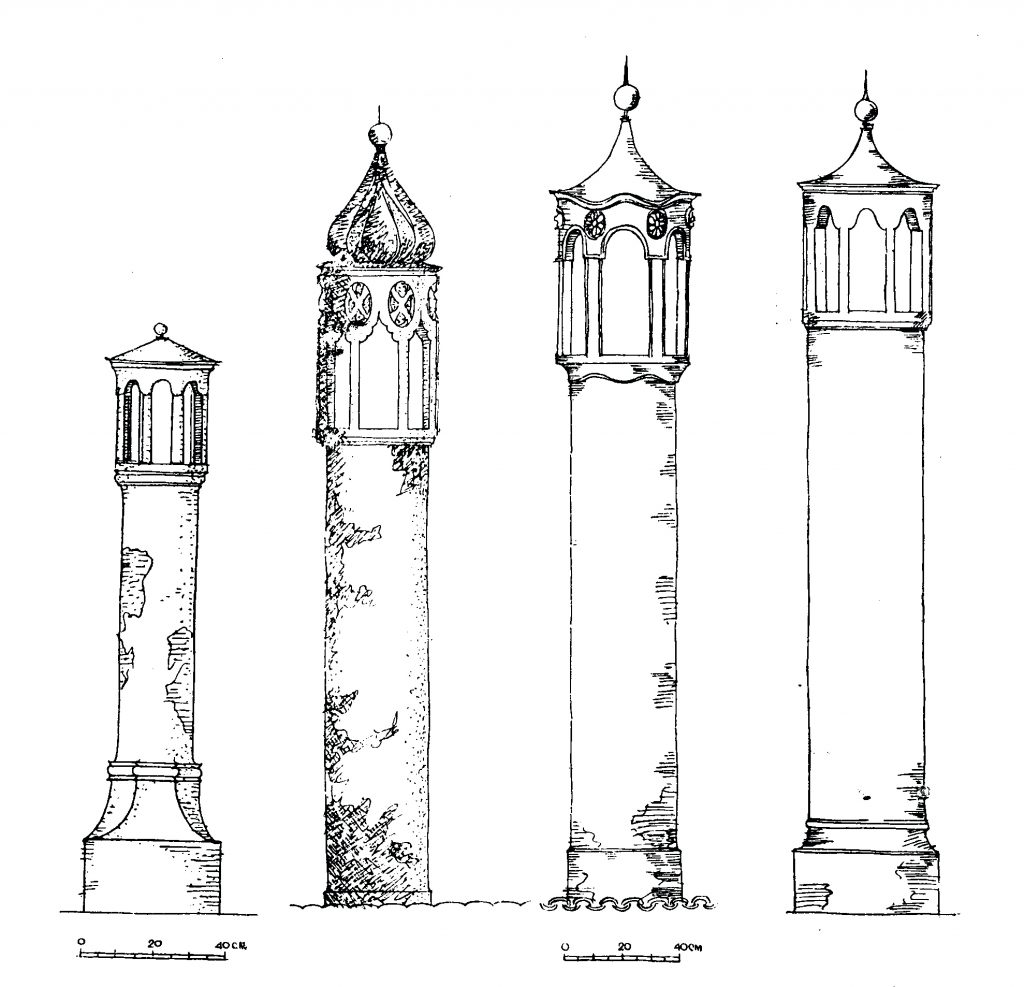

While visiting the rooms on all storeys, we find a curious element, integrated into the interior walls and richly decorated with floral ornaments of plaster or painted, small niches, etc. Is a characteristic detail of Plovdivs houses called alafranga(meaning: on the French style), which consists of an arch-shaped niche, semicircular in plan, where the stoves used to be installed. The chimneys of those stoves go upthe interior walls and come out on the roofs asbeautiful ceramic chimneys that were worthy end of the traditional houses.

Al recorrer las estancias en todas las plantas, nos encontramos con un curioso elemento, integrado en las paredes interiores y ricamente decorado con ornamentos florales de yeso o pintados, pequeños nichos, etc. Se trata de algo muy característico de las casas de Plovdiv, alafranga ( a lo francés), que consiste en un nicho con forma de arco y de planta semicircular, donde antiguamente se instalaban las estufas. Las chimeneas de dichas estufas subían por las paredes interiores y salían en las cubiertas en forma de bonitas chimeneas de cerámica que eran en sí unos dignos remates de las casas tradicionales.

The Georgiadi house, with its monumental architecture, the richness of its shapes and colors, is a living witness of the welfare of the bourgeois class of the time and the prosperity and power of the city. Nowadays, the house hosts part of the exhibition of the Historical Museum of Plovdiv, after having been restored in the sixties.

La casa Gueorguiadi, con su arquitectura monumental, la riqueza de sus formas y colores, es un vivo testigo del bienestar de la clase burguesa de la época y de la prosperidad y poder de la ciudad. Hoy en día la casa acoge parte de la exposición del Museo Histórico de Plovdiv, tras haber sido restaurada en los años sesenta.

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Image by Alexandrina Marinova

Cantilever details

Ceiling pattern detail

Clay Chimney design from Plovdiv tradition

Structural system. Walls and wooden frame

………………………………………………………………………..

Further References:

- (Título original)Пловдивската къща през епохата на Възраждането(La casa de Plovdiv en la época del Renacimiento/ Plovdiv´s house during the Revival), PEEV, Hristo, 1960, Тecnica, Sofía

- (Título original)Кратка история на българската архитектура(Historia corta de la arquitectura búlgara/ Short history of bulgarian architecture),TONEV, Lyuben, 1965, BAN, Sofía