**Article written by Phạm Phú Vinh **

Modernism diasporas can be found anywhere in the world. But in few countries, there is such a seamless transition from traditional to modernist architecture like in Vietnam.

Las diásporas del movimiento moderno se pueden encontrar en cualquier parte del mundo. Sin embargo, en pocos países, esa transición es tan fluida de la arquitectura tradicional a la moderna como en Vietnam.

Vietnam was one of the post-colonial countries that embraced modernism as the new architecture to continue their ancient cultural background. Yet unlike other post-colonial states in Southeast Asia, Vietnamese architects didn’t use ornamentation or structural imitations to project identity. Works of architects like Lê Văn Lắm (Architecte Diplômé Par Le Gouvernement, Urbaniste with a 1963 conference on The Big Problems of Paris’s Urbanism) or Ngô Viết Thụ (Grand Prix de Rome 1955) were staying true to the modernist virtues. Their buildings don’t try to make a revival of the distant traditional architecture. What they used was abstractions, and most importantly, the micro-climatic tactics that tropicalized modernism to fit in the climatic context of Vietnam. These architects, in fact, the first generation of Vietnamese architects, have investigated the new functions and aesthetics of industrial materials to come up with a vocabulary of modernist elements that were later received and embedded into the architectural culture of Vietnam.

Vietnam fue uno de tantos países poscoloniales que abrazó el movimiento moderno como un medio de continuidad con su propio trasfondo cultural. Sin embargo, a diferencia de otros estados poscoloniales del sudeste asiático, los arquitectos vietnamitas no utilizaron ornamentación o imitaciones estructurales para proyectar una identidad específica. La obra de arquitectos como Lê Văn Lắm (Architecte Diplômé Par Le Gouvernement, Urbaniste con una conferencia de 1963 sobre Los grandes problemas del urbanismo de París) o Ngô Viết Thụ (Grand Prix de Rome 1955) se mantuvieron fieles a las virtudes modernistas. Sus edificios no trataron de revivir una tradición arquitectónica lejana. Por el contrario usaron abstracciones y, sobretodo, estrategias microclimáticas que tropicalizaron el modernismo para poder adaptarse al contexto climático de Vietnam. Estos arquitectos, que además fueron la primera generación de arquitectos vietnamitas, investigaron las nuevas funciones y la estética de los materiales industriales para llegar a un vocabulario de elementos modernistas que serían incorporados a la cultura arquitectónica de Vietnam.

To understand this idea of identity to which Vietnamese architects adhere, it’s worth looking at how Vietnamese modernist architecture was influenced by Vietnamese traditional architecture and the decisions made by architects back then. A typology that shows such an influence is the villa.

Para comprender esta idea de identidad a la que se adhieren los arquitectos vietnamitas, es necesario observar cómo la arquitectura modernista vietnamita estuvo influenciada por la arquitectura tradicional vietnamita y cuáles fueron las decisiones tomadas por los arquitectos entonces. Una tipología que muestra de forma paradigmática esta influencia es la villa.

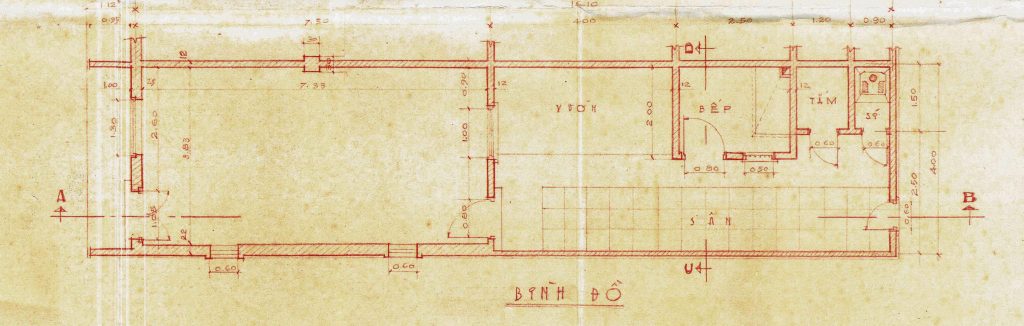

This design from the collection of Popular House Constructions from the Department of Urban Construction and Design in 1957 is a good reference to provide an overview of the state of vernacular housing after the First Indochina War that ended in 1954. The architect and the location of this design are unknown. As there is no sign of site investigation, this design could be a typical design that provides an economical housing solution for the population nation-wide.

Este proyecto, parte de la colección de Construcciones de Casas Populares del Departamento de Construcción y Diseño Urbano en 1957, es una buena referencia para proporcionar una descripción general del estado de la vivienda vernácula después de la Primera Guerra Indochina que terminó en 1954. El arquitecto y la ubicación del proyecto son desconocidos y podría ser un diseño prototípico para proporcionar una solución habitacional económica a la población de todo el país.

This house may have been an urban house as it’s closed on 2 sides and the back, suggesting the only entrance and exit to the front main road in a dense urban context. From the front to the back, the plan includes a living room, a transitional garden to the kitchen, bathroom, and toilet. The garden, the kitchen, the bathroom, and the toilet form a backhouse that opens to an interior backyard.

Se entiende que la casa está localizada en un entorno urbano ya que se cierra en sus medianeras y la parte trasera, lo que sugiere que solo se puede entrar por la fachada principal de un denso contexto urbano. Desde el frente a la parta posterior, la planta incluye una sala de estar, un jardín que se conecta a la cocina, y un aseo. El jardín, la cocina y el baño se abren a un patio interior.

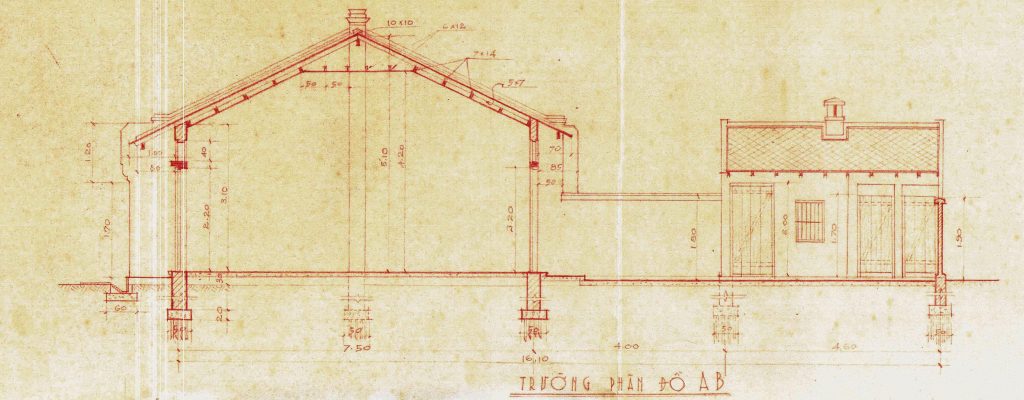

As seen in the drawings, the structure of this house was already in concrete, brick, and wood. This may prove the affordability of mass-produced industrial material in cities ever since 1957. Looking at the section, a lot of micro-climatic behaviors can be spotted. The sloped wooden roof helps drain rainwater during downpours. This roof also extends beyond the columns to create overhangs that prohibit rain splash as well as direct sunlight to the interior. Furthermore, ventilation is encouraged. Incorporated into the walls are louvers made of wooden fins above door height. Therefore, air can continuously circulate and be refreshed, lowering heat and humidity. All of these techniques informed by the climate made the house very open yet protected. In fact, the inside and the outside weren’t separated at all. They are a system of voids thoroughly connected through a system of figurative separations that play as spatial orientations.

Como se puede ver en los dibujos, la estructura de la casa era de hormigón, ladrillo y madera, lo que probaba lo asequible de los medio de producción industriales en ciudades a partir de 1957. Si miramos la sección, hay una serie de estrategias microclimáticas que pueden ser descritas: la cubierta inclinada de madera ayuda a drenar el agua de la lluvia. La cubierta también se extiende, más allá de las columnas creando un voladizo que protege el interior de la lluvia y el sol. Además, un sistema de celosías de madera situadas encima de las puertas fomentan la ventilación cruzada permitiendo que el aire circule de manera constante y se reduzca la humedad y el calor. Todos estos sistemas climáticos se abren al exterior mientras que lo protegen de él. Son un sistema de vacíos conectados mediante separaciones figurativas que crean varias relaciones espaciales orientadas.

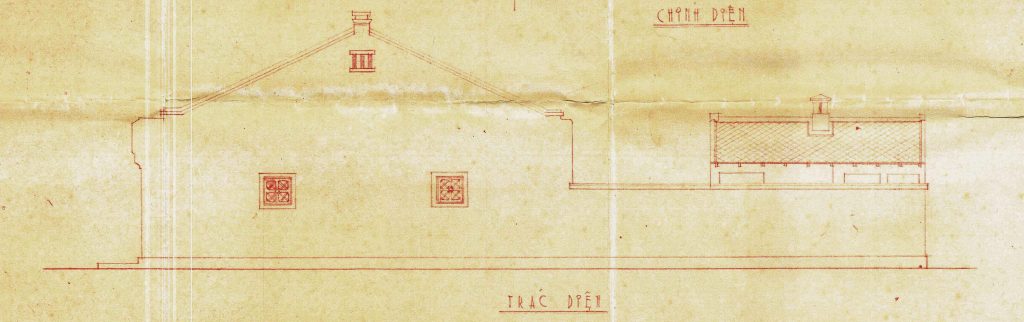

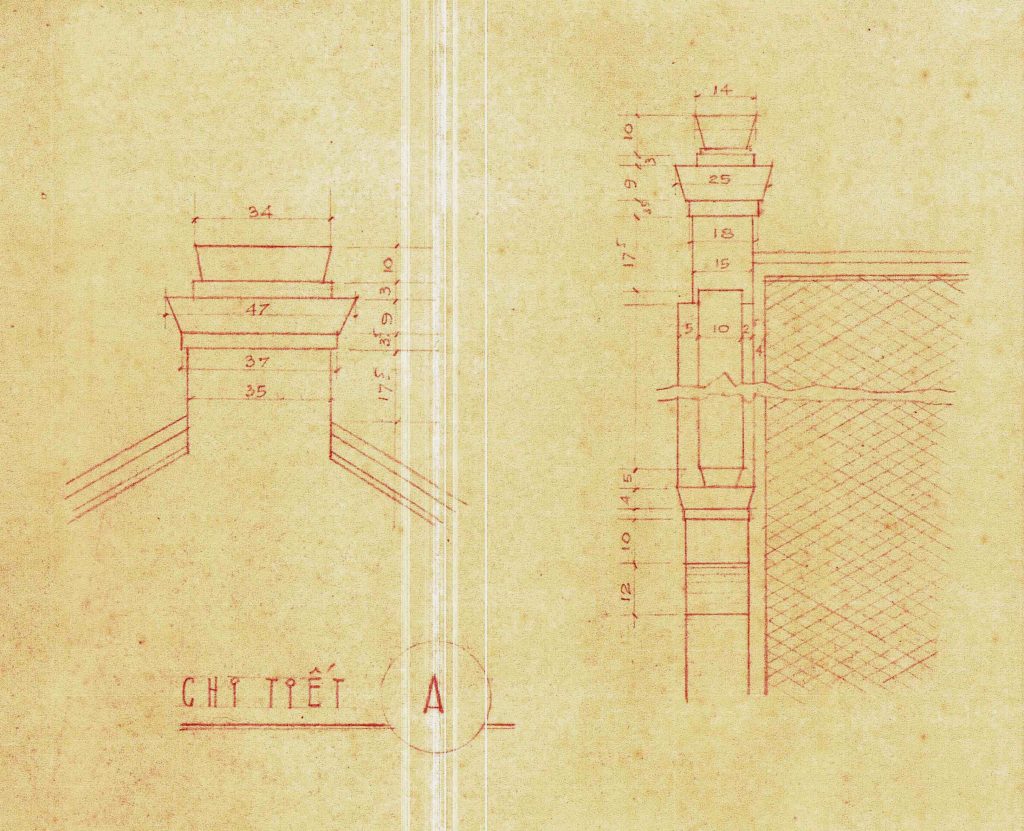

Another very interesting thing in this design is the ornamentations on the roof, walls, and windows. This detail may suggest that this house was not intended to be a modernist design, but rather an exemplary sample of vernacular architecture. Even though made of functional elements and industrial materials, these decorative touches were still required in 1957. These details recalled back to the traditional architecture of houses in northern Vietnam, the imperial palaces in Huế, or the shophouses in Hội An Ancient Town. By traditional references and the appearance of industrial materials, this popular design is a great indication of the transition from Vietnamese vernacular architecture to modernist architecture.

Otro dato interesante de este proyecto es la ornamentación de los muros, cubierta y ventanas. Estos detalles sugieres que la casa no pretendía mostrar un diseño modernista, sino más bien continuar la línea de la arquitectura vernácula. Aunque estuviera construida de elementos funcionales e industriales, estos elementos ornamentales aún eran necesarios en 1957. Estos detalles forman parte de la continuidad de la tradición arquitectónica del norte de Vietnam, los palacios imperiales en Huế o las casas de Hội, un pueblo ancestral. La mezcolanza de referencias tradicionales y materiales industriales es un indicativo de la transición de la arquitectura vietnamita de un ambiente vernáculo a uno modernista.

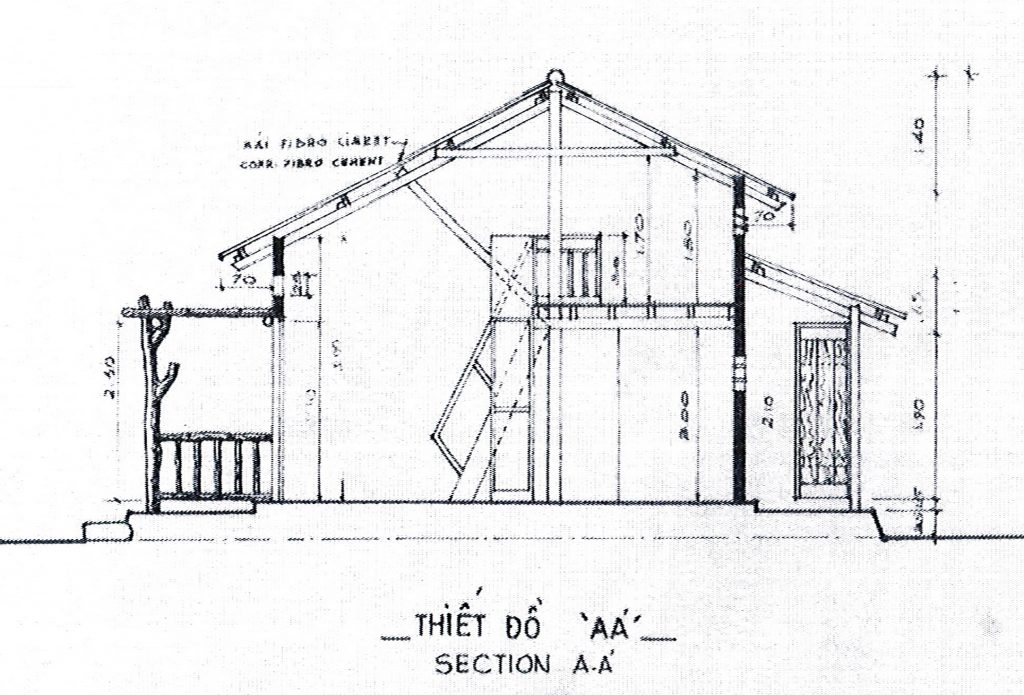

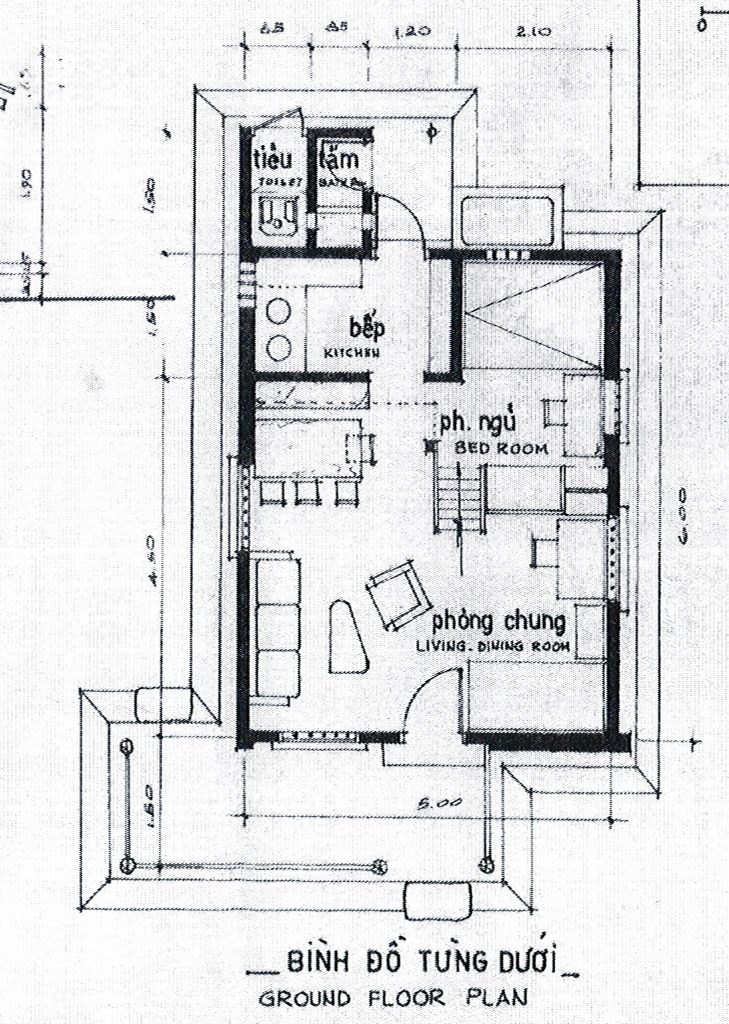

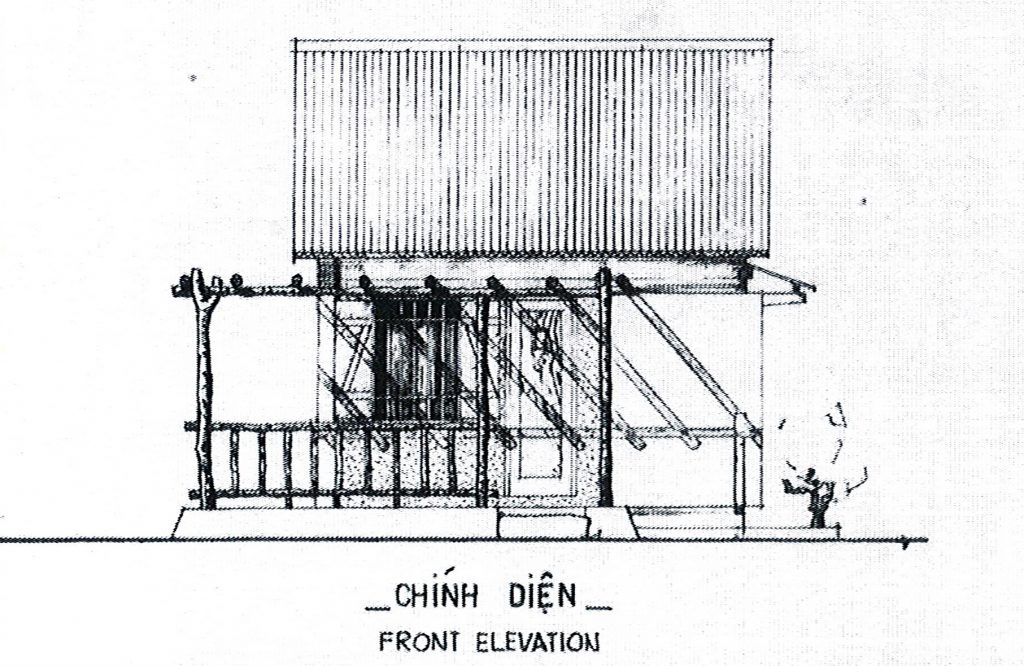

Another interesting example is this design in 1968 in the set of popular designs to provide cheap accommodation to the population who lost their houses during the Tết Mậu Thân Offensive during 1968 Lunar New Year. Another design made minimal and economical to solve housing problems, this house shows significant changes from the one in 1957. Smaller in size yet more minimal, more functional, and more modernist.

Otro ejemplo interesante es un proyecto de 1968 que proponía alojamiento económico a la población que había perdido sus casas durante la ofensiva de Tết Mậu Thân durante el Año Nuevo Lunar de 1968. Este proyecto minimalista muestra cambios sustanciales respecto al proyecto de 1957. Era más pequeño pero más funcional y modernista.

This 34.5-square-meter house has a living room, a bedroom, a kitchen, a mezzanine, a bathroom, a toilet, and last but not least, an open backyard. The structure of this house is not indicated but the thickness of the wall suggests that it’s made of bricks. The sloped and extended roofs were still made of wooden trusses with fibro-cement covering sheets as it is cheaper than a flat reinforced concrete roof. One addition to this house in comparison to the 1957 house is the extended front terrace covered by a pergola made of wood trunks. This is an extremely important detail because it relates strongly to the Terrace Culture of Vietnamese traditional architecture. This buffer zone between inside and outside, this in-between, a bit ambiguous space was actually where everything happened. It can be a pavilion, a family meeting spot, a dining room, a smoking room, even a bedroom for breezed lunch naps.

Esta casa de 34,5 metros cuadrados tiene una sala de estar, un dormitorio, una cocina, un entrepiso, un baño, un inodoro y, por último, pero no menos importante, un patio trasero abierto. La estructura de la casa es desconocida, pero el groso de los muros en los dibujos sugiere que esté hecha de ladrillos. Los techos inclinados y en voladizo aún están construidos con cercas de madera y paneles de fibrocemento, ya que esta solución era más barata que el hormigón armado. Una diferencia de esta casa respecto a la anterior es la terraza delantera cubierta por una pérgola hecha de troncos de madera. Este es un detalle extremadamente importante ya que tiene una fuerte relación con la cultura de terrazas en la arquitectura tradicional vietnamita. Este umbral entre el interior y el exterior, un espacio intermedio y ambiguo, era en realidad donde sucedía la domesticidad. Puede ser un pabellón, un lugar de reunión familiar, un comedor, una sala de fumadores o incluso un dormitorio para tomar una siesta al mediodía.

This design again shows how important ventilation and shading devices are. Louvers and overhangs are applied whenever possible. The most important feature of this house is that it is strictly modernist. Even though wooden structures were still visible, everything in this design is a systematic assemblage of mass-produced functional units. Functional and minimal parts are put together to solve pragmatic needs. There are no empirical principles imposed upon the design rather the freedom that industrial materials provide.

Este proyecto muestra nuevamente la importancia de los dispositivos de ventilación y sombreado. Siempre que era posible, se colocaban persianas y voladizos. La característica más importante de esta casa era que es estrictamente modernista. Aunque las estructuras de madera todavía eran visibles, todo el proyecto es un sistema de ensamblaje de unidades funcionales producidas en masa. Las partes funcionales y mínimas se unen para resolver necesidades pragmáticas. No se imponen principios empíricos sobre el diseño, sino la libertad que brindan los materiales industriales.

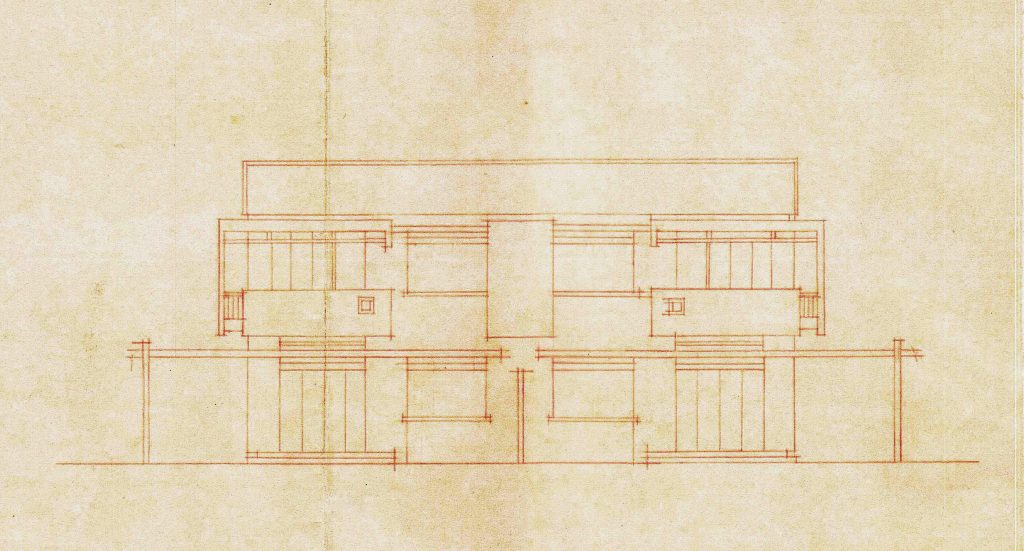

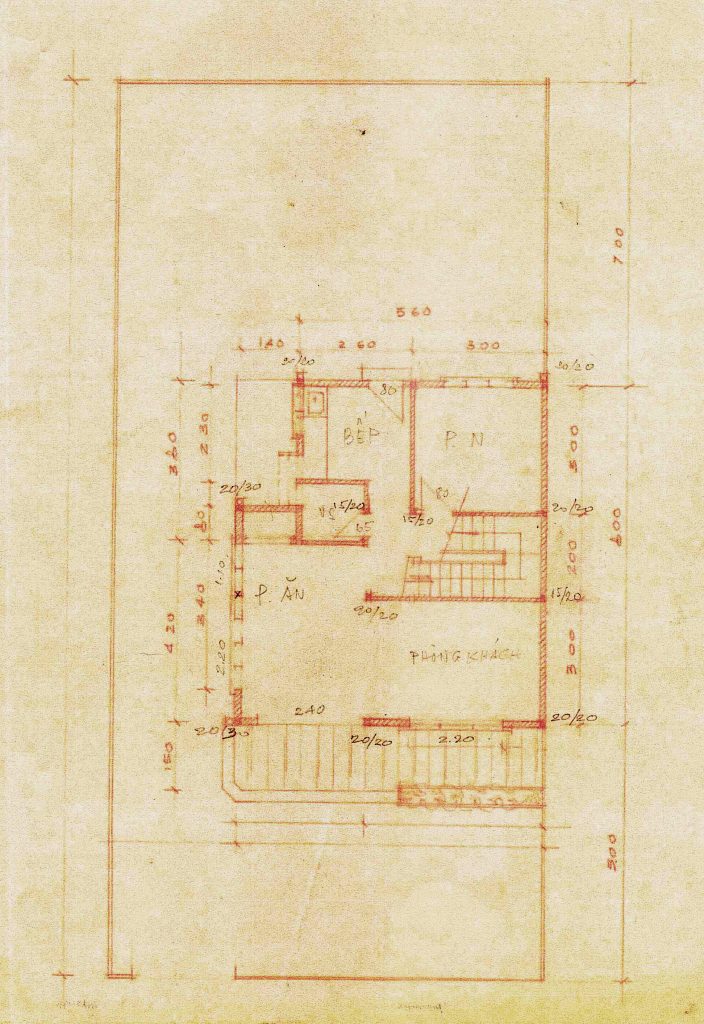

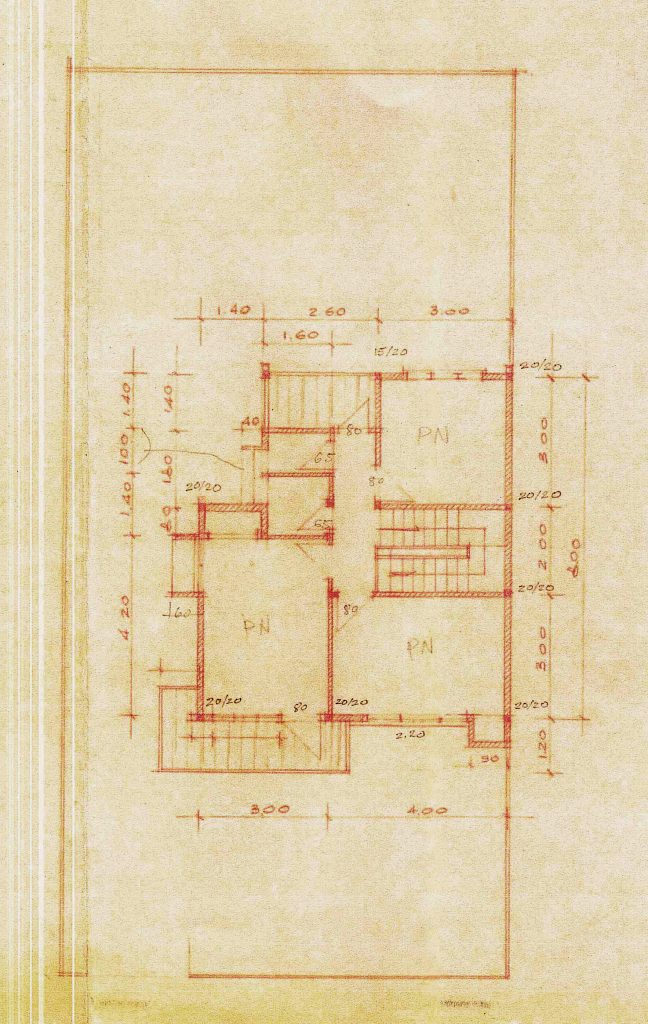

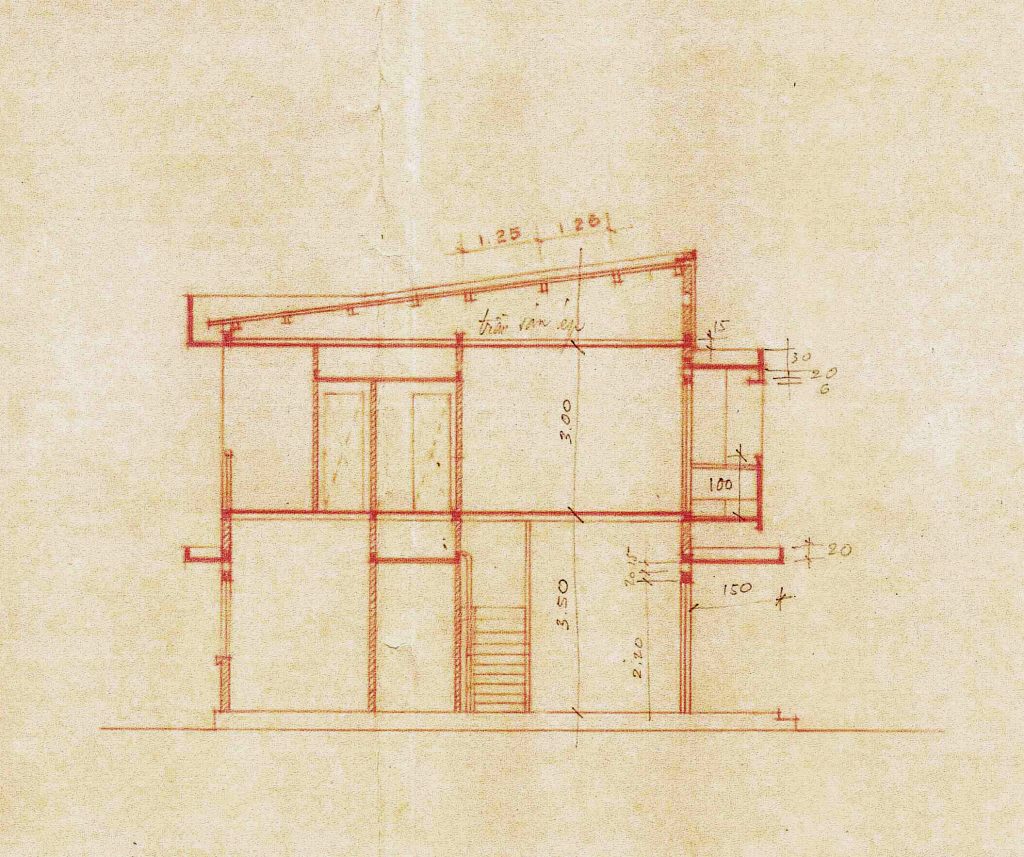

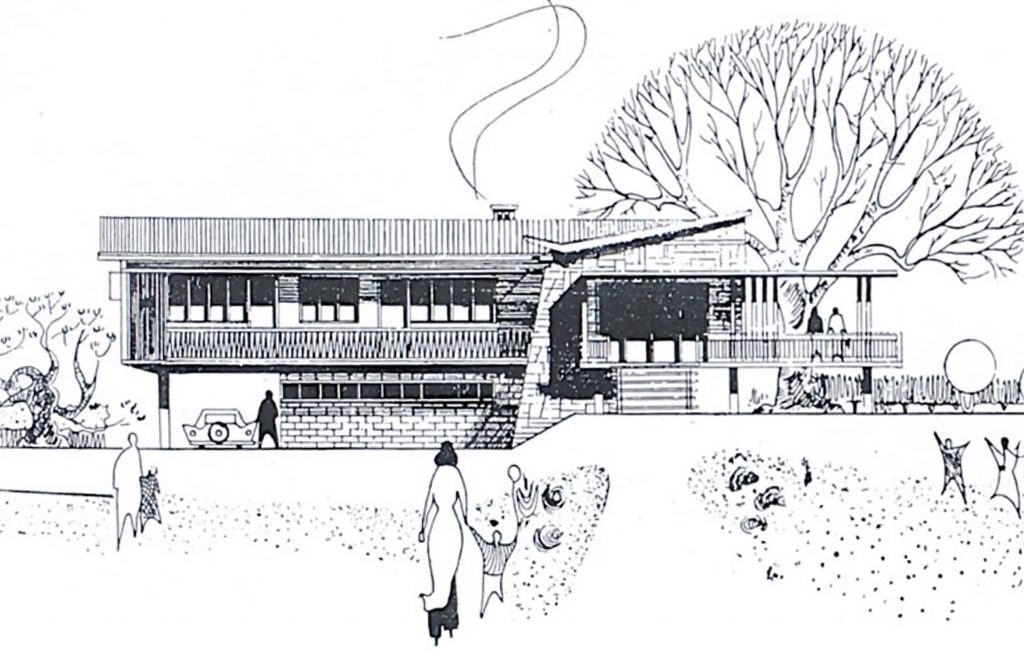

If the previous house hasn’t shown the complete modernist break, then the next villa is a great example of Vietnamese mid-century modernist architecture. Its unfinished drawings are still in the drafting stage which reveals reflection of the architect. The date of this design is not indicated but villas of this style can usually be dated to the 1960s or early 1970s.

Si el proyecto anterior no había mostrado aún una ruptura modernista, la siguiente villa es un gran ejemplo de arquitectura vietnamita de mitad de siglo. Los dibujos inacabados son aún borradores, los cuales revelan varias reflexiones del arquitecto. La fecha del proyecto no se indica pero las villas con este estilo arquitectónico suelen estar datadas en la década de 1960 y principios de los 70.

Pretty much the higher configuration of the same design, this house resembles well the 1968 house. The floor plan was composed of similar functions including one living room, one kitchen, a bathroom, a toilet, a backyard, one bedroom on the ground floor, and 3 more bedrooms on the second floor. Still present is the generous front terrace.

Prácticamente la configuración de esta casa recuerda a aquella de 1968. La planta tenía las mismas habitaciones (sala, cocina, baño, patio, una habitación en la planta baja y tres más en el piso superior). La terraza frontal es muy generosa.

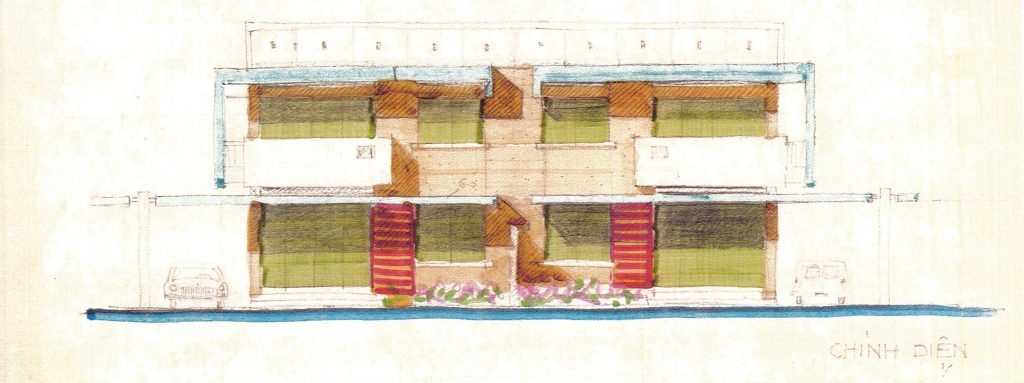

The drawings of this house show how versatile and convenient reinforced concrete was. Throughout the house are the higher versions of the same shading and ventilating devices that could be seen in the 2 previous houses. Louvers are now incorporated into window frames. Overhangs were easier to apply and extend further out of the functional body. One very interesting element is the pergola covering the front terrace. This structure now extends further to become more of a canopy to cover a bigger area of the front yard. It also plays a visual role in the composition of the facade as its strong horizontality responds artistically to other architectonic elements.

Los dibujos de esta casa muestran la versatilidad del hormigón armado. Además en toda la vivienda se encuentran versiones mejoradas de los mismos dispositivos de sombreado y ventilación que se pudieron ver en las 2 casas anteriores: Las persianas ahora están incorporadas en los marcos de las ventanas, los voladizos eran más fáciles de aplicar y se extendían más allá. Un elemento muy interesante es la pérgola que cubre la terraza delantera. Esta estructura ahora se extiende más para convertirse más en un dosel que cubre una gran área del patio delantero. También juega un papel visual en la composición de la fachada ya que su fuerte horizontalidad responde artísticamente a otros elementos arquitectónicos.

But what is most important in this modernist villa isn’t the higher version of functional organization inherited from traditional design, but it is the new architectural language that was examined. All functional elements are artistically refined rather than staying minimal. Throughout this new modernist aesthetics is the shadow, the new aesthetics that reinforced concrete structures can provide.

Pero lo más importante de esta villa modernista no son las mejoras respecto a los proyectos más tradicionales mostrados anteriormente, si no el nuevo lenguaje propuesto. Todos los elementos han sido refinados y, mediante una estética modernista, el hormigón armado provee unas soluciones más elaboradas.

Vietnamese modernist architecture shows an admirable focus on facade design, on how the functional elements on the plans and sections would appear in three-dimensional perspectives. Originated from the micro-climatic treatments, elements like louvers and overhangs create a new language of artistic expressions. Extrusions and intrusions orchestrate an interplay of solid and void, of light and shadow that breeds a kind of depth and texture, not just by the physical structures, but mostly by the shades they give.

La arquitectura modernista vietnamita muestra un asombroso trabajo en la articulación de las fachadas, y como se relacionan los elementos funcionales proyectados en planta y sección en perspectivas tridimensionales. Los sistemas microclimáticos, tales como celosías y voladizos, crean nuevas expresiones artísticas. Las extrusiones y las intrusiones orquestan una interacción entre sólido y vacío, luz y sombra, lo que provoca una profundidad y textura no solo en su propia materialización sino también en el juego de sombras que crean.

This sensitivity was later captured by the population to create modernist shophouses and rural houses that can be seen across southern Vietnam. Significantly, as mostly decided by the population itself without architects partaking, these houses are very decorative, but abstract and reflect the spirituality seen in Vietnamese vernacular architecture.

Esta sensibilidad fue capturada posteriormente por la sociedad para al construir sus propias casas y comercios que se pueden observar en el sur de Vietnam. Es significativo como estas construcciones sin arquitectos son fuertemente ornamentadas de un modo abstracto, reflejando la espiritualidad de la arquitectura vernácula vietnamita.

From the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, there’s a continuous evolution of the genealogy of Vietnamese traditional architecture into the modern age after the end of colonialism. This continuation was first proactively studied and realized by modernist architects. But it was later captured and realized both spontaneously and wide-spreadly by the culture itself. A Vietnamese house had gradually become less ornamental, more industrial, and eventually became modernist. Interior arrangement also made significant changes shown in room organization and furniture selection. Yet surviving all the transformation brought about by the new reality of the industrial economy is still indispensable micro-climatic behaviors, culture and most importantly the special taste preserved in the new architectural language.

Desde mediados de la década de 1950 hasta mediados de los 70, hay una continua evolución en la genealogía de la arquitectura tradicional vietnamita hasta construir un movimiento moderno tras el fin del colonialismo. Esta continuidad fue primeramente construida de forma proactiva por arquitectos modernistas. Pero más tarde fue capturada y realizada de manera espontánea por la cultura popular. La casa vietnamita se volvió gradualmente menos ornamental, más industrial y, finalmente, modernista. La disposición interior también tuvo cambios significativos que se muestran en la organización de las habitaciones y la selección de muebles. Sin embargo, sobrevivir a toda transformación provocada por la nueva realidad de la economía industrial sigue siendo indispensable en los comportamientos microclimáticos, la cultura y, especialmente, un nuevo lenguaje arquitectónico.

Modernist buildings have ever since become the way of making shelters in modern times, developed and realized by the Vietnamese people. The practice of modernist shophouses nowadays has started right after the country’s retrieval of cultural independence. As vernacular architecture, it is the question of ethnic and cultural specificities including architecture within that we’re dealing with. As a branch of the modern movements, how influenced was it by Vietnamese traditional architecture? Or wasn’t it the same architectural consciousness of the traditional that continued into its new conditions? The question of what was inherited and invented can be problematic and fundamental at the same time.

Los edificios modernistas se han convertido desde entonces en la forma de construir refugios por el pueblo vietnamita. La práctica modernista en la actualidad ha comenzado justo después de la recuperación de la independencia cultural del país. Como arquitectura vernácula, estamos tratando con la cuestión de las especificidades étnicas y culturales, incluida la arquitectura. Como rama de los movimientos modernos, ¿qué influencia tuvo la arquitectura tradicional vietnamita? ¿O no fue la misma conciencia arquitectónica de lo tradicional que continuó en sus nuevas condiciones? La cuestión de qué se ha heredado e inventado puede ser problemática y fundamental al mismo tiempo.

One very promising opportunity is that this branch of modernism shows signs and features of the agricultural age where architecture was practiced as habits, customs, or traditions, with taste and vernacular sensitivity. Even though we’re far from this past, the circle of agricultural life was in fact a sustainable circle that was both environmentally and culturally responsive. Can modern architecture and our modernity create this mechanism of subconscious responses embedded within our culture to solve the problem of global warming and sustainability? Vernacular modernism may have a good story to tell.

Una oportunidad muy prometedora es que esta rama del modernismo muestra signos y rasgos de la época agrícola donde la arquitectura se practicaba como hábitos, costumbres o tradiciones, con gusto y sensibilidad vernácula. A pesar de que estamos lejos de este pasado, el círculo de la vida agrícola era de hecho un círculo sostenible que respondía tanto al clima como a la cultura ¿Puede la arquitectura moderna y nuestra propia modernidad crear este mecanismo de respuestas subconscientes incrustadas en nuestra cultura para resolver el problema del calentamiento global y la sostenibilidad? El modernismo vernáculo puede tener una buena historia que contar.

Extended research for the book Poetic Significance, Sài Gòn Mid-Century Modernist Architecture, published in 2021 by Architecture Vietnam Books

Phạm Phú Vinh is a writer on Vietnamese mid-century modernist architecture. He spent roughly 5 years capturing and analyzing this architecture that creates the urban landscape as well as the identity of Saigon where he lives. His works focus on the unorthodox architecture made by the population as a culture besides individual architects. His newest book, “Poetic Significance, Sài Gòn Mid-Century Modernist Architecture”, presents and discusses the often neglected yet carefully-crafted vernacular modernist architecture that he believes to have hosted the Vietnamese architectural identity in the modern age.”

Phạm Phú Vinh es un escritor sobre arquitectura modera vietnamita de mediados de siglo. Estuvo cinco años realizando una investigación sobre la arquitectura de este país para crear un paisaje urbano así como dela identidad de Saigon, donde él vive. Su trabajo se centra en lo poca ortodoxa arquitectura realizada por parte de la población al margen de los arquitectos. Su nuevo libro “Poetic Significance, Sài Gòn Mid-Century Modernist Architecture”, reflexiona sobre la arquitectura vernácula modernista y su tesis defiende que es ésta la que ha albergado la la identidad arquitectónica vietnamita contemporánea.