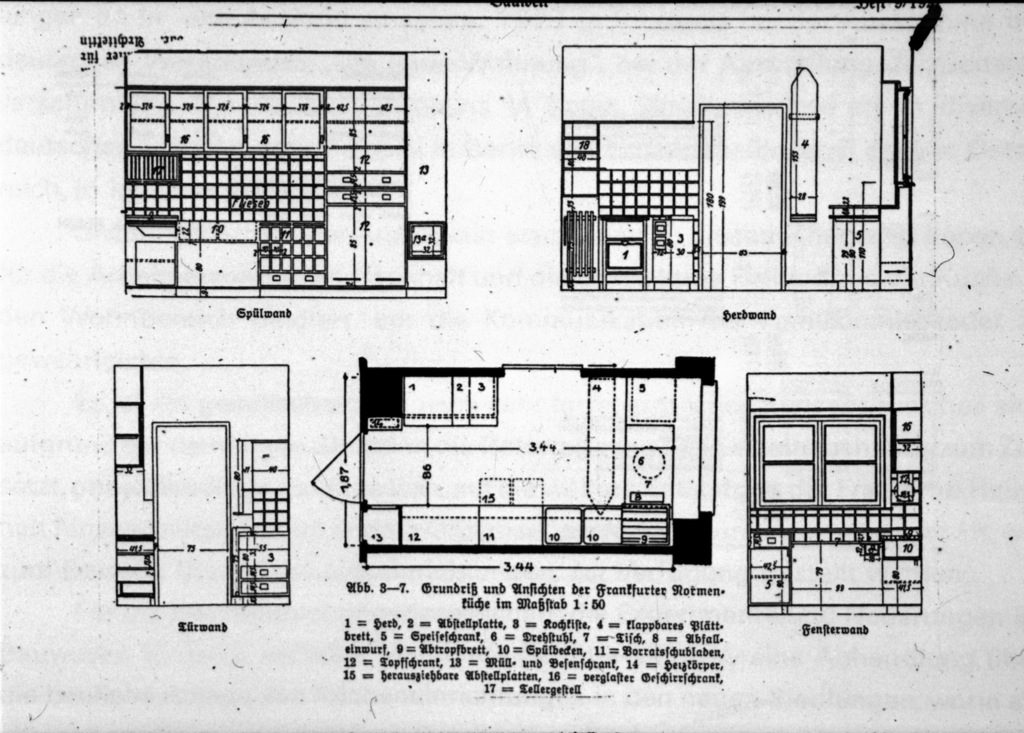

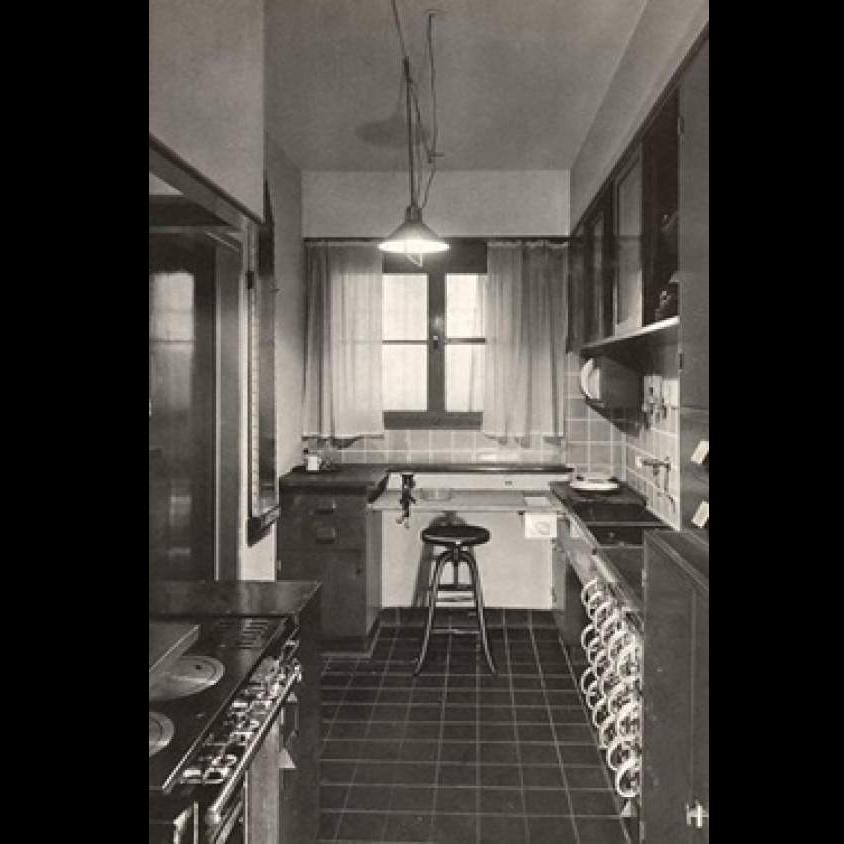

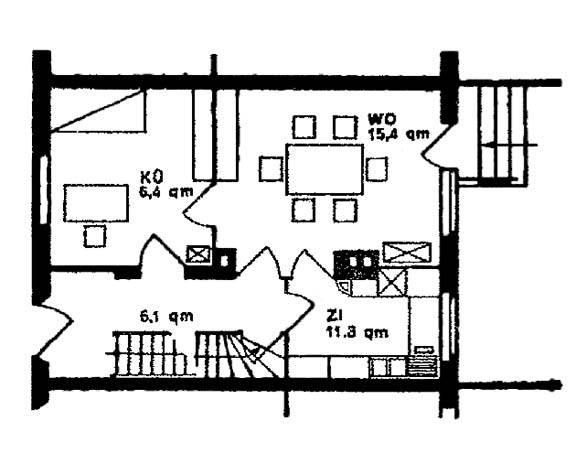

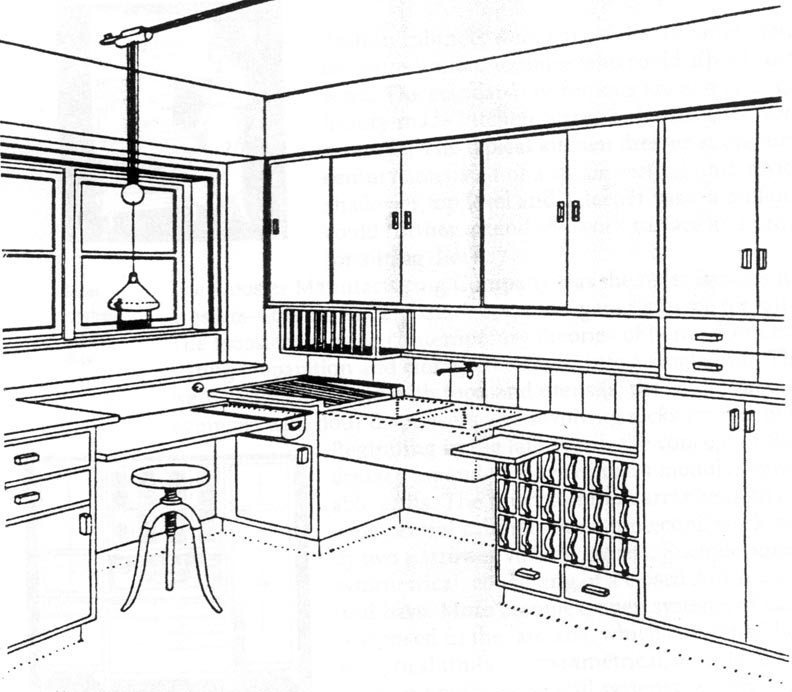

The prototype of the Frankfurt Kitchen, designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in the 1920s for the Römerstadt Social Housing complex in Frankfurt, was probably the largest revolution in social housing in the 20th century. Until that moment, social worker housing were divided into two main rooms: the first one was used to cook, as a bathroom and even as a bedroom, while the second room was used mainly as a living area. The model of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky separated the kitchen from the living area through a sliding door, clearly differentiating the work area from the relaxation area.

El prototipo de la Cocina Frankfurt, diseñada por Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky en los años 20 para el complejo de vivienda Social Römerstadt en Frankfurt, fue seguramente la mayor revolución en el modelo de vivienda social en el Siglo XX. Hasta aquel momento, las viviendas de los trabajadores se dividían en dos estancias principales: en el primero de ellos, además de cocinar, uno se bañaba, comía e incluso dormía, mientras que la segunda estancia se utilizaba principalmente como área de estar. El modelo de Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky separaba la cocina de la zona de estar mediante una puerta corredera diferenciando claramente la zona del trabajo de la de relajación.

“The problem of rationalising the housewife’s work is equally important to all classes of the society. Both the middle-class women, who often work without any help [i.e. without servants] in their homes, and also the women of the worker class, who often have to work in other jobs, are overworked to the point that their stress is bound to have serious consequences for public health at large.”

“El problema de racionalizar el trabajo del ama de casa es igualmente importante para todas las clases de la sociedad. Las mujeres de la clase media, que trabajan a menudo sin ninguna ayuda (es decir, sin servidumbre) en sus hogares, y también las mujeres de clase trabajadora clasifican, que tienen que trabajar a menudo en otros trabajos, sobre exponiéndose al punto que su tensión está al límite, pudiendo tener consecuencias serias para la salud pública a la larga.”

— Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in Das neue Frankfurt, 5/1926-1927

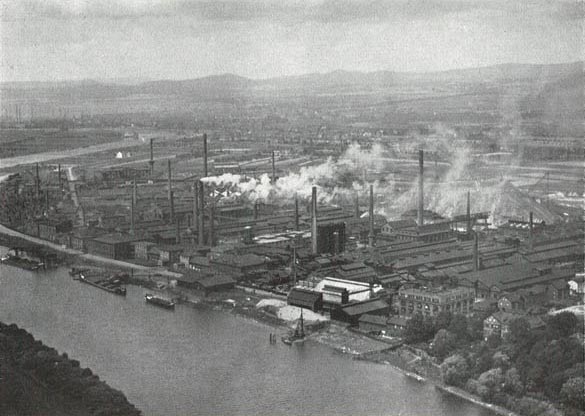

There was a lack of public housing in Germany after First World War that led to the construction of large-scale projects for a large number of working-class families, repeating a single typological model to reduce labor costs. For the social housing of the architect Ernst May some 10 000 units of Frankfurt Kitchen were built, making it an unprecedented commercial success.

En el contexto histórico y político de Alemania tras la Primera Guerra Mundial, la escasez de vivienda desembocó en la construcción de proyectos a gran escala donde para una gran cantidad de familias de clase obrera, repitiendo un único modelo tipológico para reducir los costes de obra. Para las viviendas sociales del arquitecto Ernst May se construyeron unas 10 000 unidades de Cocina Frankfurt convirtiéndolo en un éxito comercial sin precedentes.

On the other hand, the kitchen became an object of the emancipation of women. In the decade of the 20s and a totally macho family environment, women began to work in factories, having to also perform household tasks, a fact that caused them long hours of work and exposure to diseases. The Frankfurt Kitchen, although it did not modify the decompensation in the domestic tasks, did allow by means of industrial optimization concepts applied to the home, reducing the time of work women spent in kitchens with the creation of a functional kitchen and liberating the woman from long hours of work at home after spending the day in the factory. Initially, the kitchen was also perceived as a place of emancipation for the woman inside the home improving her own status. However, this initial perception began to be criticized from feminist circles in the 70s when it became clear that the kitchen had gone from being a place of emancipation of women in the home to becoming a space of confinement. In addition, the adjusted proportions that had been used to reduce costs prevented more than one person from using the kitchen at the same time, becoming at the end a domestic space purely relegated to the role of women’s work.

Por otro lado, la cocina se convirtió en un objeto de la emancipación de la mujer. En la década de los años 20 y un ambiente familiar totalmente machista, las mujeres empezaron a trabajar en las fábricas, teniendo que realizar también las tareas domésticas del hogar, un hecho que les provocaba largas jornadas de trabajo y exposición a enfermedades. La Cocina Frankfurt pese a que no modificaba la descompensación en las tareas domésticas, sí permitía mediante conceptos de optimización industrial aplicados al hogar, reducir el tiempo de trabajo en las tareas domésticas con la creación de una cocina funcional y liberando a la mujer de largas horas de trabajo en el hogar después de trabajar en la fábrica. Inicialmente, también se percibió la cocina como un lugar de emancipación para la mujer dentro del hogar mejorando su propio estatus. No obstante, esta percepción inicial se empezó a criticar desde círculos feministas en los años 70 al hacerse patente que la cocina había pasado de ser un lugar de emancipación de la mujer en el hogar a convertirse en un espacio de confinamiento. Además las ajustadas proporciones que se habían usado para abaratar costes impedía que más de una persona pudiera utilizar la cocina al mismo tiempo, convirtiéndose al final en un espacio doméstico puramente relegado al papel del trabajo de la mujer.