***Article written by Julian Mändl***

Over decades Bad Gastein, a small mountain village nestled deep in the eastern part of the Austrian Alps, held the title of being one of the most fashionable and mundane spas in Europe and was a recurring meeting place for international society. This cultural upswing culminated around the fin de siecle when it soon became the annual venue for visits by Kings and Kaisers alike of all the monarchies in the German-speaking sphere. With grand society came grand architecture. The countless multi-story hotel complexes in the style of classicism and art nouveau made it the purest architectural and urbanistic self-representation of the monarchy, rivaled only by the imperial architecture of Viennas Ringstrasse or Munichs Residenz palace. It was during this period that several of Gastein’s most important buildings were erected, which to this day – although no longer in their former glory – make up the unique charm of the spa town. Friedrich Achleitner, a renowned critic defined the architectural fascination unbrokenly in the fact that in an alpine, partly wild-romantic topography a metropolitan architecture was built, which represents the greatest conceivable contrast to the natural scenery. That was, however, before this homogenic Zuckerbäcker-style of urban structure was broken irrevocably in form of several uniquely identifiable, wildly utopian brutalist buildings erected by the architect Gerhard Garstenauer to overcome the constant state of economic decline afflicting Gastein since the two world wars. In an unprecedented effort a city council tried to rejuvenate and revitalize a run-down alpine spa of former global importance with the help of modern architecture. Over the span of a decade, beginning in the mid-1960s, three buildings by Garstenauer – a public bath, a convention center, and futuristic ski lifts – breathed new life into the fading Bad Gastein and helped, for it to become a contemporary and aspirational tourist destination once again.

Durante décadas, Bad Gastein, un pequeño pueblo de montaña enclavado en lo más profundo de los Alpes austriacos, ostentó el título de ser uno de los balnearios más de moda y mundanos de Europa y fue un lugar de encuentro recurrente para la sociedad internacional. Este auge cultural culminó en torno al fin de siglo, cuando pronto se convirtió en el lugar de visita anual de reyes y kaisers de todas las monarquías del ámbito germano hablante. Con la gran sociedad llegó la gran arquitectura. Los innumerables complejos hoteleros de varios pisos de estilo clasicista y art nouveau la convirtieron en la más pura autorrepresentación arquitectónica y urbanística de la monarquía, sólo rivalizada por la arquitectura imperial de la Ringstrasse vienesa o el palacio Residenz de Múnich. Fue en esta época cuando se levantaron varios de los edificios más importantes de Gastein, que hasta hoy -aunque ya no tienen su antiguo esplendor- conforman el encanto único de la ciudad balneario. Friedrich Achleitner, un crítico de renombre, definió la fascinación arquitectónica de forma ininterrumpida en el hecho de que en una topografía alpina, en parte salvaje-romántica, se construyera una arquitectura metropolitana que representa el mayor contraste concebible con el paisaje natural. Sin embargo, eso fue antes de que este homogéneo estilo Zuckerbäcker de estructura urbana se rompiera irremediablemente en forma de varios edificios brutalistas de carácter único y utópico erigidos por el arquitecto Gerhard Garstenauer para superar el constante estado de decadencia económica que afectaba a Gastein desde las dos guerras mundiales. En un esfuerzo sin precedentes, el ayuntamiento trató de rejuvenecer y revitalizar un balneario alpino degradado de antigua importancia mundial con la ayuda de la arquitectura moderna. En el transcurso de una década, a partir de mediados de los 60, tres edificios de Garstenauer -un baño público, un centro de convenciones y unos remontes futuristas- insuflaron nueva vida a la decadente Bad Gastein y contribuyeron a que volviera a ser un destino turístico contemporáneo y con aspiraciones.

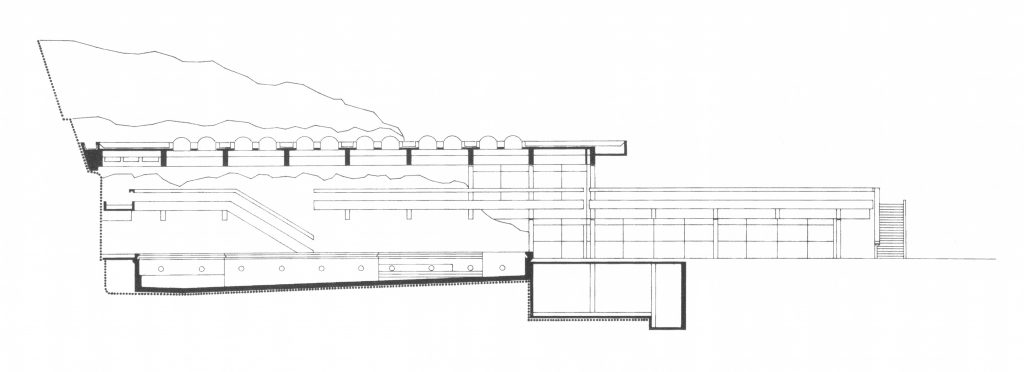

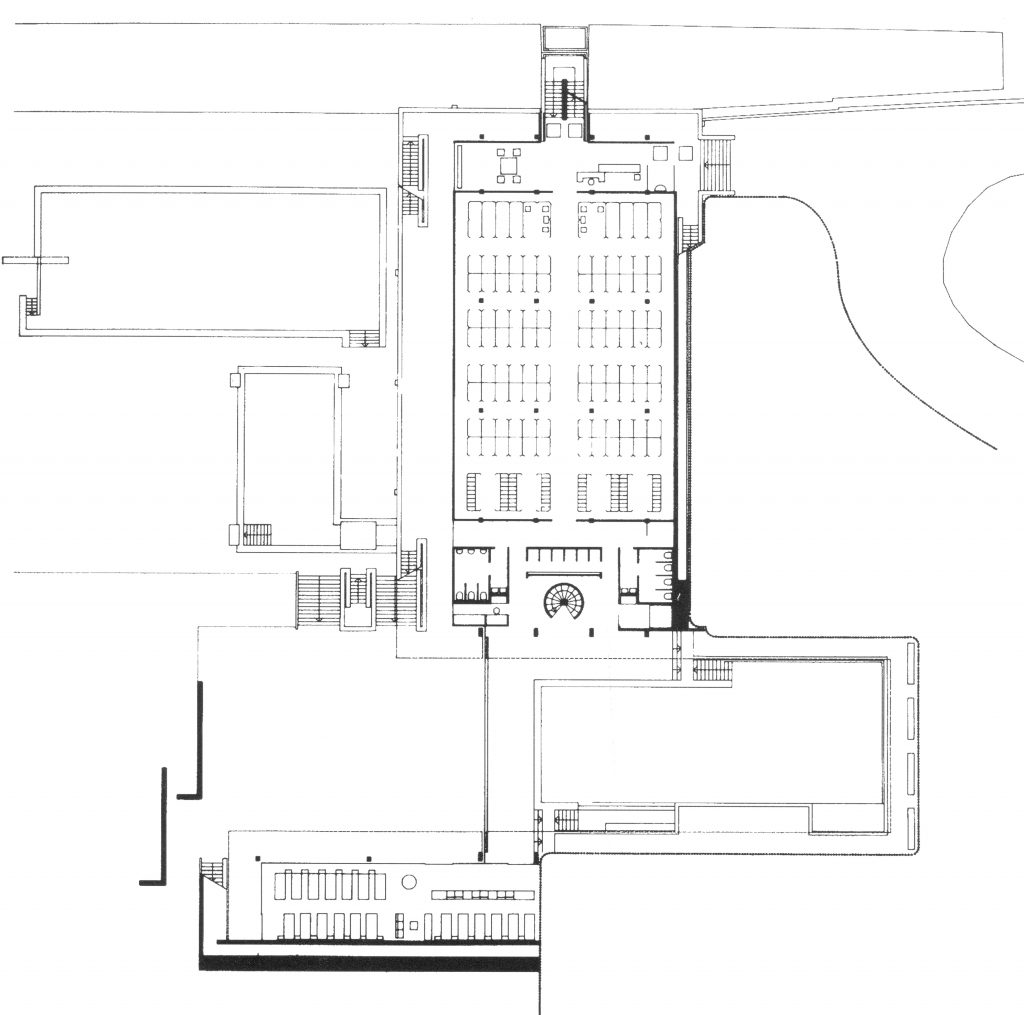

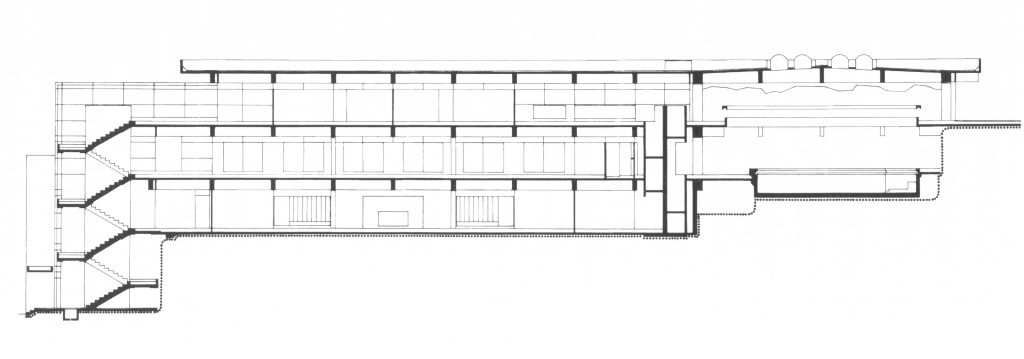

In an attempt to reintroduce the traditional bathing culture to a younger generation, the revitalization found its first execution with the Felsenbad (1966-1968), which directly translated means as much as spa in the mountains. One of the determining factors for the name-giving idea was the prevailing lack of space. A large bathing hall, the main room of the entire complex, could not find a place on the existing building area limited by a mountain hillside and therefore had to be broken out of the rocky ridge on site. The raw rock, however, was not fearfully cladded in a protective manner, but rather incorporated into the design of the structure as a natural spatial boundary and a formative aesthetic design element.

En un intento de reintroducir la cultura del baño tradicional a una generación más joven, la revitalización encontró su primera ejecución con el Felsenbad (1966-1968), que traducido directamente significa balneario en las montañas. Uno de los factores determinantes de la idea de dar nombre al balneario fue la falta de espacio imperante. Una gran sala de baño, la sala principal de todo el complejo, no podía encontrar un lugar en la zona de construcción existente, limitada por la ladera de la montaña, por lo que tuvo que ser arrancada de la cresta rocosa del lugar. Sin embargo, la roca en bruto no se revistió de forma protectora, sino que se incorporó al diseño de la estructura como un límite espacial natural y un elemento de diseño estético formativo.

An elongated main structure with a flat roof contains the bathing hall as well as changing rooms and a restaurant. It is opened to the south by a horizontally structured glass front and leads to sun terraces and the outdoor pool with a panoramic view of the Alps. To the east, a low transverse wing houses the resting hall. Typical for the style of brutalist buildings of this time, the main building material is pure fair-faced concrete in combination with floor-to-ceiling glass fronts and wooden profiles. In the interior, glass mosaic clads the floors and walls of the wet areas, and wood paneling counters the cool character of rock and concrete.

Una estructura principal alargada con techo plano contiene la sala de baño, así como los vestuarios y un restaurante. Está abierta al sur por una fachada acristalada de estructura horizontal y conduce a las terrazas y a la piscina exterior con una vista panorámica de los Alpes. Al este, un ala transversal baja alberga la sala de descanso. Típico del estilo de los edificios brutalistas de esta época, el material principal de construcción es el hormigón visto puro en con frentes de cristal del suelo al techo y perfiles de madera. En el interior, el mosaico de vidrio reviste los suelos y paredes de las zonas húmedas, y los paneles de madera contrarrestan el carácter frío de la roca y el hormigón.

The opening of the spa attracted supra-regional attention for the outstanding architectural structure; within a year, over a million tourists visited this unprecedented form of a public bath. In its execution and its connection with nature, the Felsenbad is an outstanding document of this particular period and one of the few internationally acclaimed and published architectures in the region of Salzburg. After several centuries of use and modernized standards for bathing culture, the public bath was extended in several stages by two cubic volumes, always to the disadvantage of the architectural character intended by Garstenauer. The description of the visual impression refers to the original construction in its environment.

La apertura del balneario atrajo la atención suprarregional por su extraordinaria estructura arquitectónica; en un año, más de un millón de turistas visitaron esta forma inédita de baño público. Por su ejecución y su conexión con la naturaleza, el Felsenbad es un documento excepcional de esta época concreta y una de las pocas arquitecturas de la región de Salzburgo aclamadas y publicadas internacionalmente. Después de varios siglos de uso y de la modernización de las normas de la cultura del baño, el baño público se amplió en varias etapas con dos volúmenes cúbicos, siempre en detrimento del carácter arquitectónico que pretendía Garstenauer. La descripción de la impresión visual se refiere a la construcción original en su entorno.

Sources

Friedrich Achleitner, Österreichische Architektur im 20. Jahrhundert – Band 1, Salzburg: Residenz Verlag, 1980

Gerhard Garstenauer et al.: Interventionen, Salzburg: Pustet Verlag, 2002

All images and plans, excepting the ones subtitled, are from:

Gerhard Garstenauer et al.: Interventionen, Salzburg: Pustet Verlag, 2002

***

Julian Mändl is currently working on the master thesis for a diploma at University of Technology in Vienna, having enjoyed previous architectural education in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Particular interests include all things beautiful, the significance of architectural history and the ways in which political ambitions, economic interests and institutional structures shape the aesthetics of the ubiquitous built environment.