***

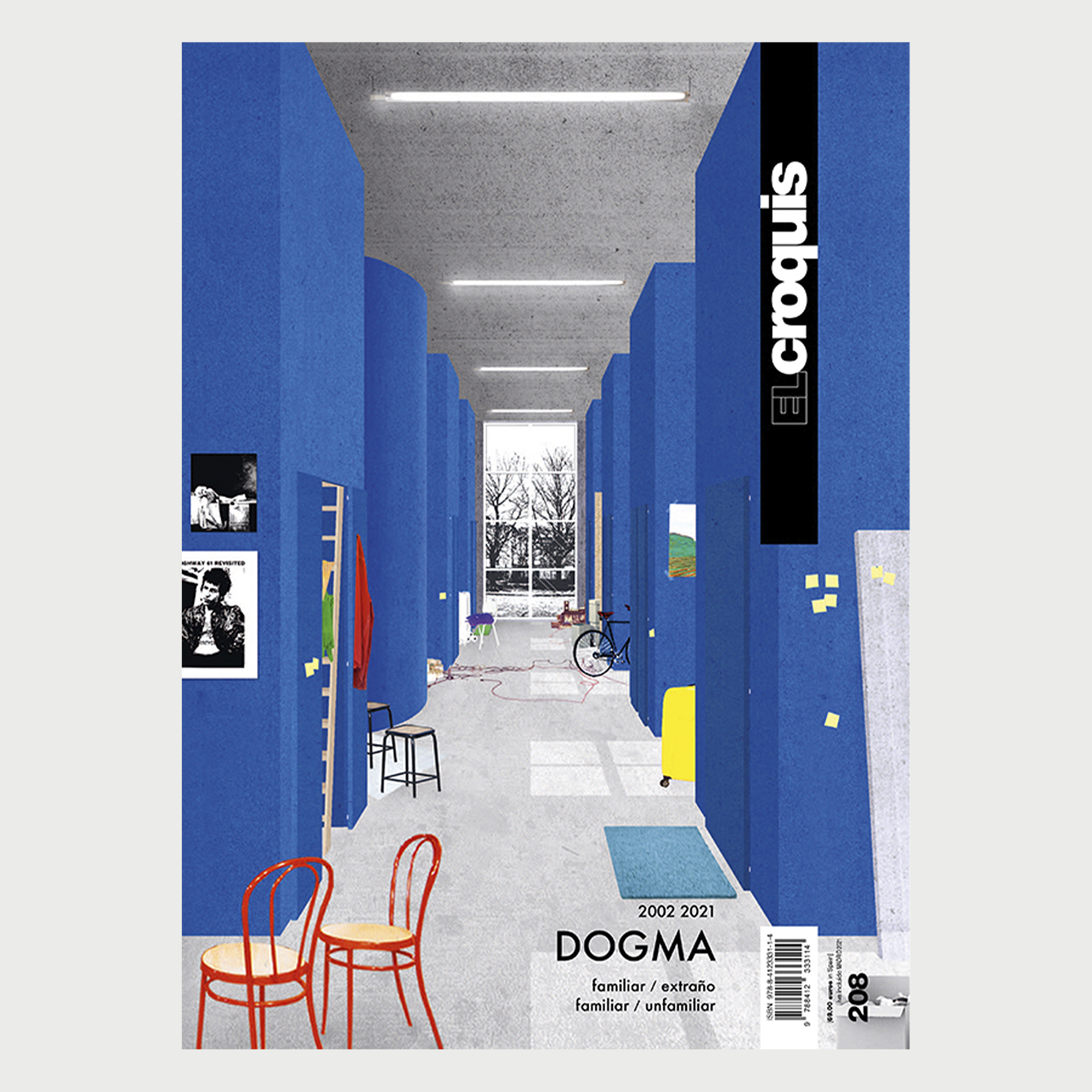

Title: El Croquis 208. Dogma 2002.2021

Authors: Fernando Márquez Cecilia and Richard Levene

Edited by: El Croquis

2021. ISBN: 978-84-120034-3-7

Language: Spanish and English

303 pages

***

“For us no complexities, no contradictions,… no diagrams, no icons, no data, no programs, no mapping, no statistics, no blobs, no parametric formalism, no icons…no non-standard architecture… no originality, no novelty, no newness, no nostalgia, no sixties, no utopia. no irresponsibility, no life-mirroring… no coercion”

“Por nosotros, no a las complejidades, no a las contradicciones… no a los diagramas, no a los iconos, no a los datos, no a los programas, no al mapeado, no a las estadísticas… no a lo informe, no al formalismo paramétrico, no a los iconos… no a la arquitectura no estándar… no a la originalidad, no a la novedad, no a lo novedoso, no a la nostalgia, no a los sesenta, no a la utopía… no a la irresponsabilidad, no al reflejo de la vida, no a la coerción.”

Dogma, Architecture Refuses, Manifesto Marathon, Serpentine Gallery. 2008

“There is a growing interest in more socially oriented ways of living, such as co-housing or sharing domestic space beyond the single-family housing complex. But what is rarely mentioned is that these forms of living require little effort. Living together requires less individual freedom, although that may not be a bad thing. The question is whether such forms of living should be developed only for economic needs, or whether it is only by sharing and living together that we can regain the true subjectivity that Karl Marx described so beautifully with the oxymoron “social individuals”: individuals who only really become individuals among other individuals. In this case less means precisely recalibrating a form of reciprocity that is no longer driven by possession, but by the act of sharing; the less we have in terms of possessions, the more we are able to share. To say enough (rather than more) means redefining what we really need to live a good life; that is, a life detached from the social value of property, from the anxiety of production and possession, and where less is simply enough.”

“Existe un interés cada vez mayor en las formas de vida de mayor orientación social, como el co-housing o el compartir el espacio doméstico más allá del complejo de la vivienda unifamiliar. Pero lo que rara vez se menciona es que estas formas de vida requieren un pequeño esfuerzo. La convivencia exige una menor libertad individual, aunque puede que eso no sea algo malo. La cuestión es si deben desarrollarse tales formas de vida tan solo por necesidades económicas, o si es sólo compartiendo y conviviendo como podemos recuperar la verdadera subjetividad que Karl Marx describió tan bellamente con el oxímoron “individuos sociales”: individuos que solo llegan realmente a serlo entre otros individuos. En este caso menos significa precisamente recalibrar una forma de reciprocidad que ya no está impulsada por la posesión, sino por el acto de compartir; cuanto menos tengamos en términos de posesiones, más seremos capaces de compartir. Decir suficiente (en lugar de más) significa redefinir lo que realmente necesitamos para vivir una buena vida; es decir, una vida desapegada del valor social de la propiedad, de la ansiedad de la producción y de la posesión, y donde menos sea simplemente suficiente.”

Pier Vittorio Aureli. Less is Enough. 2013

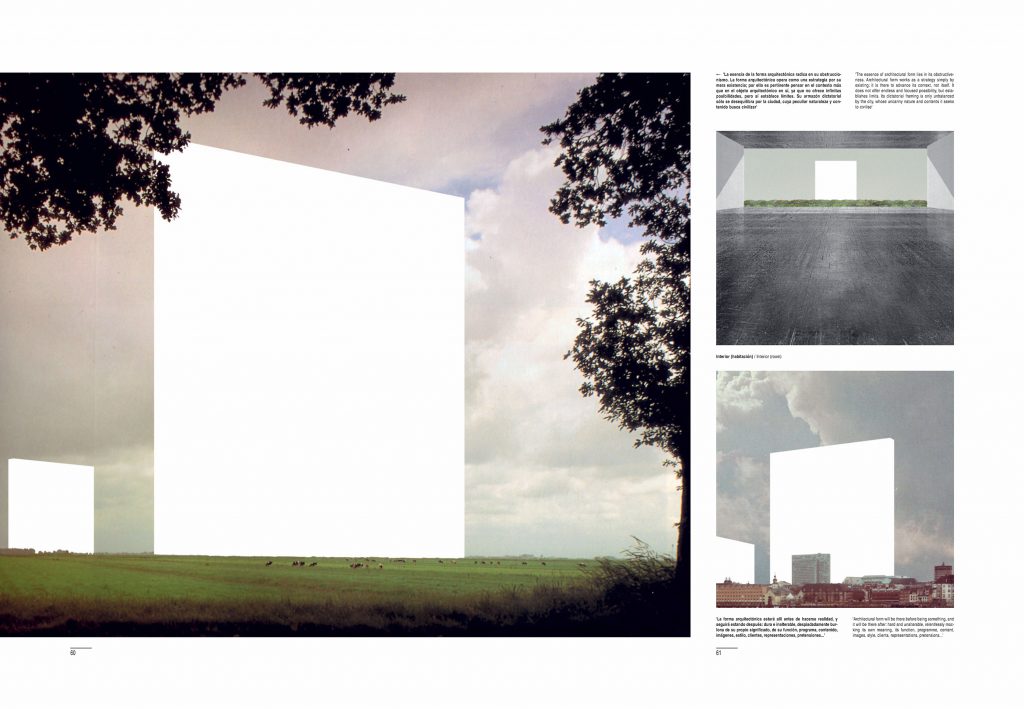

In 2015 Madrid City Council called a public competition for the remodelling of Plaza de España. Encouraged by the possibility of contributing to the construction of a critical debate on the intervention in a capital area of the city, we got together with a group of friends and decided to apply. Without the intention of developing a “feasible proposal”, we set ourselves the objective of trying to contribute some ideas or strategies that were hitherto unconventional when it came to intervening on a large scale in consolidated urban centres. At that time, Dogma’s work was not particularly well known in the Spanish architectural sphere. We had already located some of his collages that were circulating on the web and which had begun to build a “school” in other countries. With the hyperrealist representation of digital renderings as the hegemonic reference, the analogue composition of these architectural perspectives presented a force of communication that was very refreshing. Through the use of resources such as central perspectives and classical compositional framing, the application of textures in an abstract way, the incorporation of ordinary objects constructing a narrative of everyday domestic life or the particular use of the human figure, these perspectives were capable of transmitting very focused ideas about a particular approach to the architectural matter.

En el año 2015 el Ayuntamiento de Madrid convocó un concurso público para la remodelación de la Plaza de España. Animados por la posibilidad de contribuir a la construcción de un debate crítico sobre la intervención en una zona capital de la ciudad, nos reunimos un grupo de amigos y decidimos presentarnos. Sin la intención de desarrollar una “propuesta realizable”, nos fijamos como objetivo tratar de aportar unas ideas o estrategias hasta ahora poco convencionales a la hora de intervenir a gran escala en centros urbanos consolidados. Por aquella fecha, el trabajo de Dogma no era especialmente conocido en el ámbito arquitectónico español. Nosotros habíamos localizado ya alguno de sus collages que circulaban por la web y que en otros países habían comenzado a construir “escuela”. Con la representación hiperrealista de los renders digitales como referencia hegemónica, la composición analógica de estas perspectivas arquitectónicas presentaba una fuerza de comunicación que resultaba muy refrescante. Mediante la utilización de recursos como las perspectivas centrales y encuadres de composición clásica, la aplicación de texturas de forma abstracta, la incorporación de objetos ordinarios construyendo una narrativa de la cotidianeidad doméstica o el particular uso de la figura humana, estas perspectivas eran capaces de transmitir una serie de ideas muy bien enfocadas sobre una aproximación determinada al problema arquitectónico en cuestión.

Our aim of using the proposal for Plaza de España as a means of highlighting certain realities that had hitherto been overlooked gave us the possibility of getting to know Dogma’s first projects in greater depth. Beyond the aforementioned strategies of representation, we were able to delve deeper into the capacity to highlight certain social or urban problems in specific physical contexts through the abstract use of very elementary architectural archetypes or almost generic urban forms. Beyond generating an architectural or urban reality within the framework of the Vitruvian “Venustas”, the aim of their proposals was always to propose alternative intervention strategies from an ideological stance clearly based on opposition to the capitalist system. With an attitude condemned to defeat in the framework of a professional architectural competition, these proposals nevertheless have a much stronger capacity to reveal problems than conventional approaches, and the critical residue they leave behind is capable of having a much more lasting impact and enduring over time.

Nuestro objetivo de utilizar la propuesta para Plaza de España como medio para poner en evidencia determinadas realidades hasta entonces soslayadas nos brindó la posibilidad de conocer los primeros proyectos de Dogma con mayor profundidad. Más allá de las estrategias de representación anteriormente citadas, pudimos profundizar en la capacidad de revelar determinadas problemáticas sociales o urbanas en contextos físicos concretos mediante una utilización abstracta de arquetipos arquitectónicos muy elementales o formas urbanas casi genéricas. Más allá de generar una realidad arquitectónica o urbana dentro del marco de la “Venustas” vitruviana, el objetivo de las propuestas de Dogma era siempre desarrollar estrategias alternativas de intervención desde una postura ideológica claramente asentada en la oposición al sistema capitalista. Con una actitud condenada a la derrota en el marco de un concurso de arquitectura profesional, estas propuestas poseen sin embargo una capacidad de visibilizar problemáticas mucho más fuerte que las aproximaciones convencionales, y el poso crítico que dejan es capaz de repercutir y perdurar en el tiempo de manera mucho más duradera.

“Although I sympathize more with the social ambitions of the architect as activist than with the uncritical celebration of the city as a mere conglomerate of complexities and contradictions, I believe that both still underestimate (in good or bad faith) the power of architecture even in its traditional format-as a discipline concerned with the design of buildings-to influence the reality of our urban condition.”

“Aunque simpatizo más con las ambiciones sociales del arquitecto como activista que con la celebración acrítica de la ciudad como un mero conglomerado de complejidades y contradicciones, creo que ambos todavía subestiman (de buena o mala fe) el poder de la arquitectura incluso en su formato tradicional -como disciplina preocupada por el diseño de edificios- para incidir en la realidad de nuestra condición urbana.”

Pier Vittorio Aureli. Means to an End. The Rise and Fall of the Architectural Project of the City.

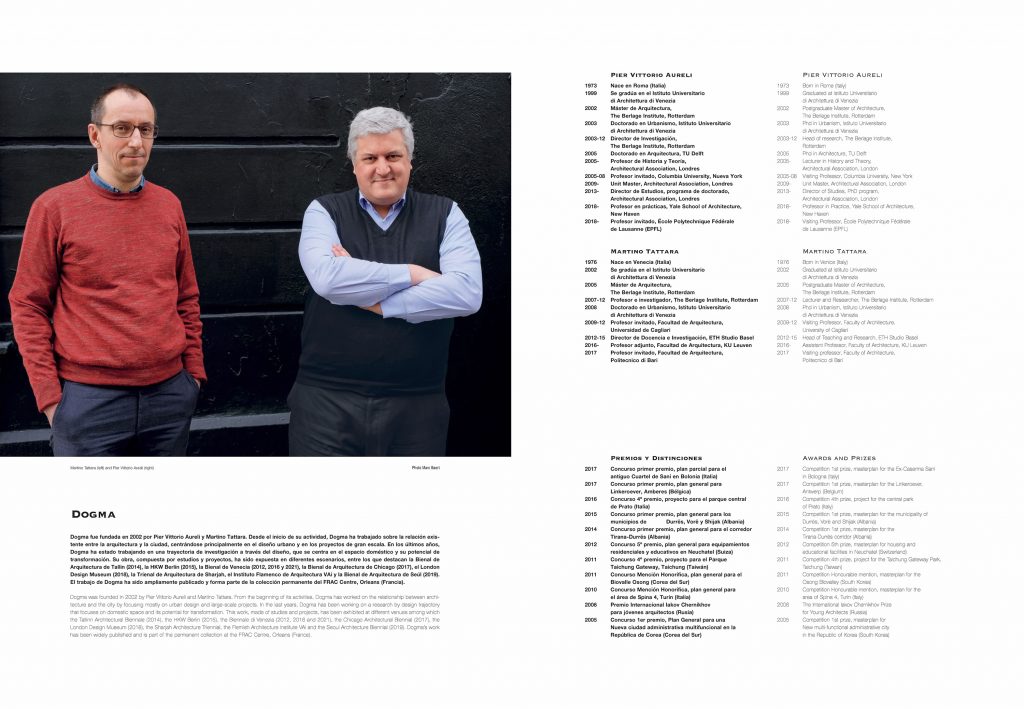

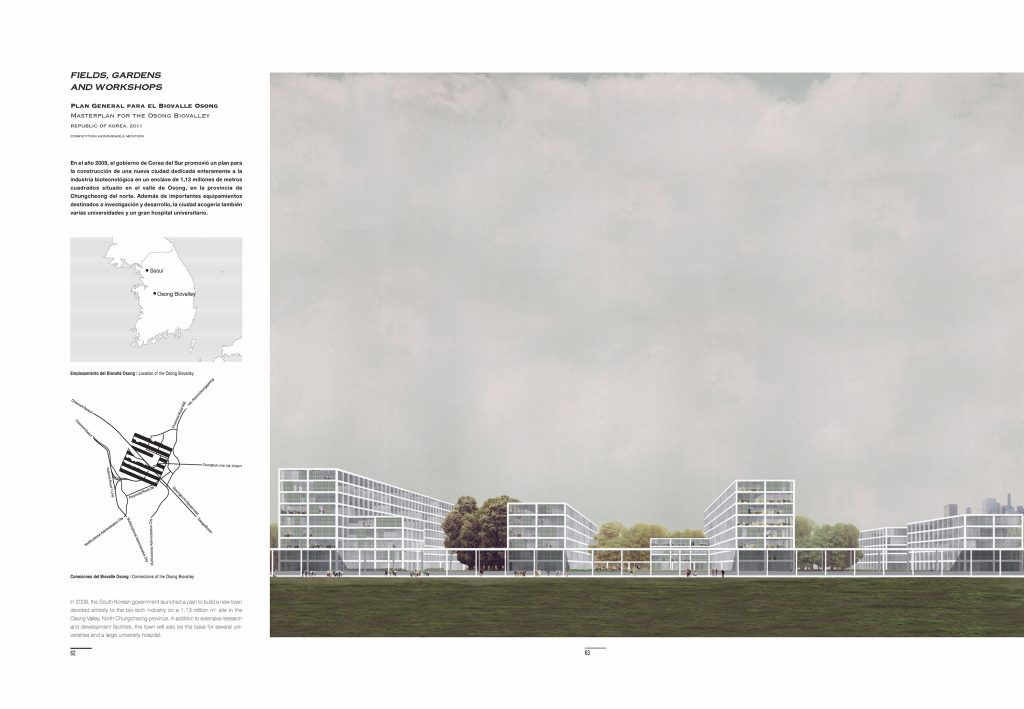

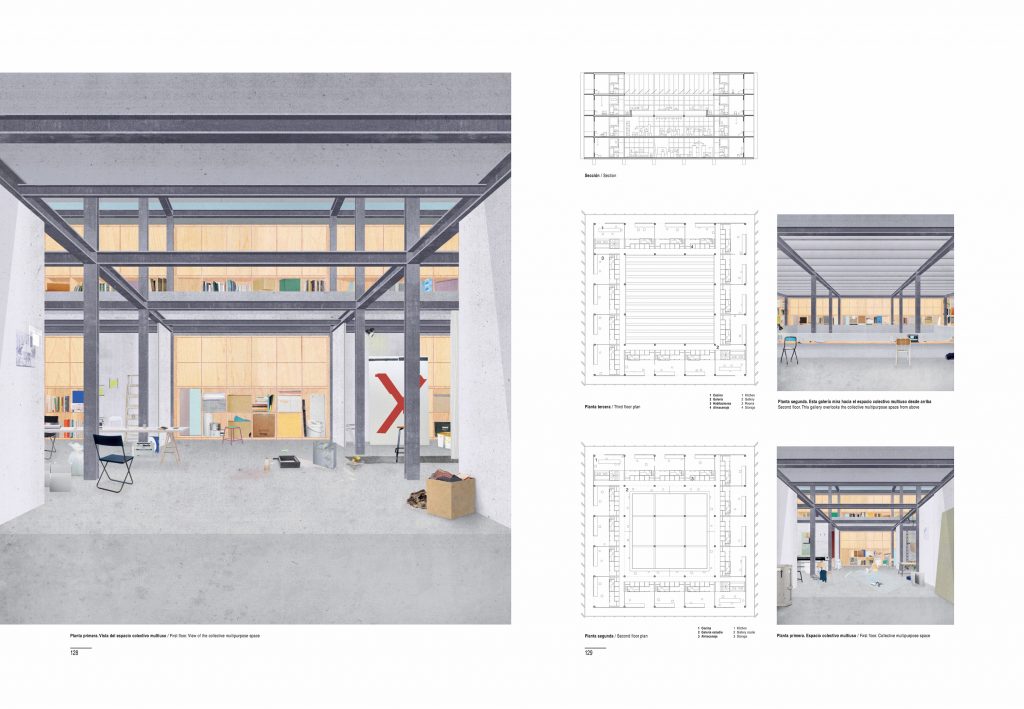

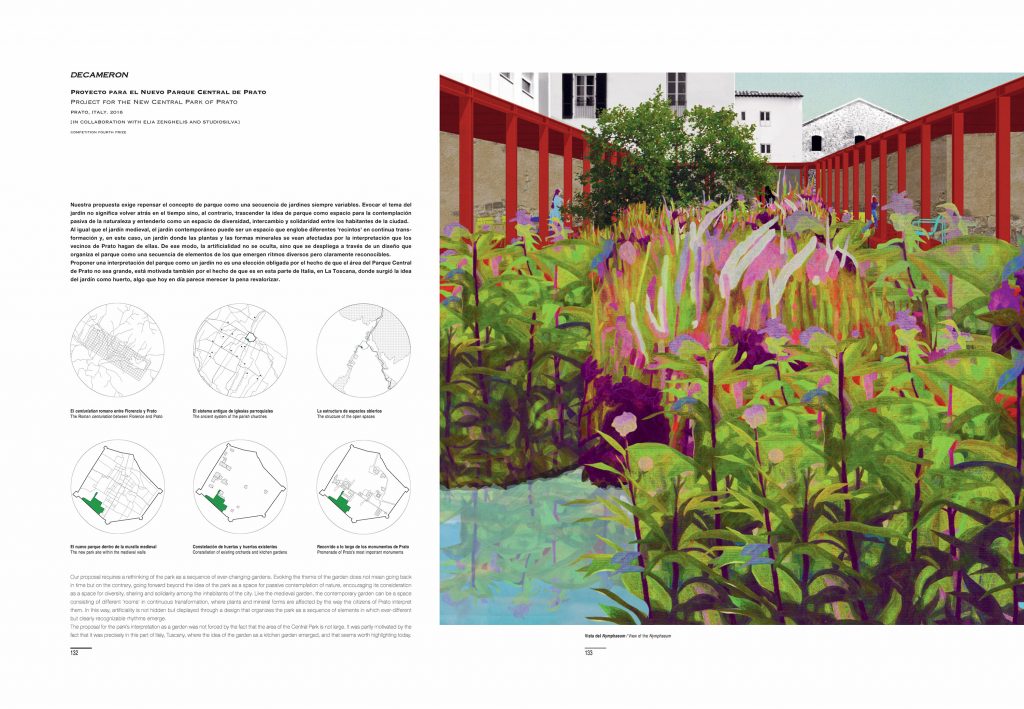

Martino Tattara and Pier Vittorio Aureli initially trained at the Venice School in the late 1990s, a time when the presence of characters such as Aldo Rossi and Manfredo Tafuri was still very dominant. Later, while continuing their training at the Berlage Institute in Rotterdam, in the early 2000s, the two began to collaborate on a stable basis as Dogma, submitting proposals for various public competitions, the first of which was in Greece with their mentor Elia Zenghelis. Since then, they have developed an intense teaching, research, exhibition and, above all, propositional activity through their participation in competitions in different countries around the world. Throughout their two decades of experience, their work can be classified into two distinct groups according to the scale and subject of their interest. Firstly, and covering approximately the first decade of work, we find their proposals more focused on the urban and metropolitan scale, highlighting the different problems of the post-fordist city resulting from the current voracious neoliberal system. Gradually, their proposals focused on more controlled territorial spheres and developed an interesting discussion around domestic space, contributing new reflections deduced from their historical analysis of different models of collective life where the barriers between public and private corresponded to logics different from those we are used to in the city created by capitalist dynamics. Recently, they have incorporated reflections on domesticity from feminist activism, which has allowed them, if possible, to develop a broader and more complex vision of the problem of how the individual fits into a collective, a city or a society. Their latest projects on collective housing investigate strategies of communal living that transcend the design of the architectural object, more interested in finding suitable frameworks for public management or land use beyond the exploitation of private land ownership.

Martino Tattara y Pier Vittorio Aureli se formaron inicialmente en la Escuela de Venecia a finales de los años 90, momento en que la presencia de figuras como Aldo Rossi y Manfredo Tafuri era todavía muy dominante. Posteriormente, mientras continuaban su formación en el instituto Berlage de Rotterdam, a inicios de los 2000, los dos comienzan a colaborar de manera estable como Dogma, presentando propuestas para diferentes concursos públicos, siendo el primero de ellos en Grecia de la mano de su mentor Elia Zenghelis. Desde ese momento han desarrollado una intensa actividad docente, de investigación, expositiva y, principalmente, propositiva a través de su participación en concursos en diferentes países del mundo. A lo largo de sus dos décadas de trayectoria su trabajo se podría clasificar en dos grupos bien diferenciados por la escala y el objeto de su interés. En primer lugar, y abarcando aproximadamente la primera década de trabajo, nos encontramos con sus propuestas más centradas en la escala urbana y metropolitana, poniendo de manifiesto las diferentes problemáticas de la ciudad postfordista resultado del actual y voraz sistema neoliberal. Poco a poco sus propuestas fueron centrándose en ámbitos territoriales más controlados y desarrollando una interesante discusión en torno al espacio doméstico, aportando nuevas reflexiones deducidas del análisis histórico de diferentes modelos de vida colectiva donde las barreras entre público y privado se correspondían con lógicas diferentes a las que estamos acostumbrados en la ciudad gestada por las dinámicas capitalistas. Recientemente han incorporado reflexiones sobre la domesticidad procedentes del activismo feminista, lo que les ha permitido, si cabe, desarrollar una visión más amplia y compleja sobre el problema del encaje del individuo en un colectivo, una ciudad o una sociedad. Sus últimos proyectos sobre vivienda colectiva investigan estrategias de vida en común que trascienden el diseño del objeto arquitectónico, más interesadas en encontrar los marcos idóneos de gestión pública o de uso del terreno más allá de la explotación de la propiedad privada del suelo.

In parallel to the more proactive side that would orbit around Dogma, Pier Vittorio Aureli has developed in recent decades an intense work as an architecture critic, becoming almost certainly the most relevant person in this field today. His texts present an ideological and social commitment that is unusual in the discipline of architecture, so accustomed to serving the powers hosting it. Titles such as “Less is Enough”, “The City as a Project” or “The Project of Autonomy. Politics and Architecture within and against Capitalism” construct a theoretical and ideological framework perfectly coordinated with Dogma’s project proposals, culminating in what would become one of the essential theoretical works of the last decades, “The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture”, recently translated into Spanish.

De forma paralela a la vertiente más propositiva que orbitaría en torno a Dogma, Pier Vittorio Aureli ha desarrollado en las últimas décadas una intensa labor como crítico de arquitectura, convirtiéndose casi con total seguridad en la figura más relevante en ese ámbito en la actualidad. Sus textos presentan un compromiso ideológico y social fuera de lo común en la disciplina de la arquitectura, tan acostumbrada siempre a servir a los poderes que la acogen. Títulos como “Menos es Suficiente”, “The City as a Project” o “The Project of Autonomy. Politics and Architecture within and against Capitalism” construyen un marco teórico e ideológico perfectamente coordinado con las propuestas proyectuales de Dogma, culminando en la que sería una de la sobras teóricas esenciales de las últimas décadas, “The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture”, recientemente traducida al castellano.

“Yet our architecture is based on a very limited grammar of forms which we constantly repeat and refine through each project. I’m not sure we should call this grammar ‘universal’, because universality is a problematic concept, but it is certainly as generic as possible. By repeating and refining a set of limited forms, we try to sharpen and make intelligible a confrontation with the context, physical as well cultural and social. In all our projects the initial design move is always the imposition of a finite form that acts as a frame. This form-as-frame is both integral in its own right but is also very much able to react to what is already there.”

“Nuestra arquitectura se basa en una gramática de formas muy restringida que constantemente repetimos y afinamos en cada proyecto. No estoy seguro de poder calificarla de universal, la universalidad es un concepto problemático, pero sí, ciertamente, de ser lo más genérica posible. Con ese repetir y pulir constantemente un conjunto de formas limitadas intentamos afinar y hacer inteligible una confrontación con el contexto, física pero también cultural y social. En todos nuestro proyectos, el gesto proyectual inicial es siempre la imposición de una forma finita que actúa como marco. Esta “forma como marco” es integral por derecho propio, pero también capaz de reaccionar a lo que ya está allí.”

Dogma, page 10

Now, after this extended but well-deserved introduction, the purpose of this article is none other than to present the publication of issue 208 of “El Croquis”, an issue dedicated to the Brussels-based office and entitled “Dogma 2002-2021. Familiar / Strange”. Our first reaction on discovering that El Croquis was going to dedicate a monograph to Dogma’s work was one of absolute surprise. A constant in the trajectory of El Croquis, which has been reflected in its editorial line, has been its pragmatic approach to the built architectural object, always giving preference to professional practices that executed projects over more speculative practices or those focused on more academic debates. Without leaving aside a profound critical approach to the different practices they have published through the texts that accompanied the projects, the aim of El Croquis has always seemed to be to offer the greatest possible graphic information on projects built or in the process of being built. On the other hand, Dogma’s work throughout its two decades of practice has been totally delimited in the field of theoretical criticism from an affirmed ideological position or, if one prefers, from a speculative approach more typical of the academic sphere than of professional offices. As an example, during this time they are not known to have built a single work. Only a few first prizes in competitions which, to date, have not transcended as projects in the process of being executed. With these premises, how would Dogma’s work fit into a publication such as El Croquis? How can we establish a relationship between these two agents who are so far apart a priori?

Ahora bien, después de esta extendida pero bien merecida introducción, el objeto de este artículo no es otro que presentar la publicación del número 208 de “El Croquis”, número dedicado a la oficina afincada en Bruselas y que lleva por título “Dogma 2002-2021. Familiar / Extraño”. Nuestra primera reacción al conocer que El Croquis iba a dedicar un monográfico sobre el trabajo de Dogma fue de absoluta sorpresa. Una constante en la trayectoria de El Croquis, que así ha quedado reflejada en su línea editorial, ha sido la de su aproximación pragmática al objeto arquitectónico construido, dando preferencia siempre a prácticas profesionales que ejecutaban proyectos por encima de prácticas más especulativas o enfocadas a debates más académicos. Sin dejar de lado una profunda aproximación crítica a las diferentes prácticas que han publicado mediante los textos que acompañaban los proyectos, el objetivo de El Croquis ha parecido siempre ser el de ofrecer la mayor información gráfica posible sobre proyectos construidos o en proceso de construcción. Por otro lado, la obra de Dogma a lo largo de sus dos décadas de práctica ha quedado totalmente delimitada en el campo de la crítica teórica desde un afirmado posicionamiento ideológico o, si se prefiere, desde una aproximación especulativa más propia del ámbito académico que de las oficinas profesionales. Como muestra, a lo largo de este tiempo no se le conoce ninguna obra construida. Tan sólo algunos primeros premios en concursos que, hasta la fecha, no han trascendido como proyectos en proceso de ser ejecutados. Con estas premisas, ¿cómo encajaría el trabajo de Dogma en una publicación como El Croquis? ¿Cómo se establece una relación entre estos dos agentes a priori tan alejados?

The publications on Dogma’s work that have appeared to date have had at least two common characteristics. The first of these is the focus on a very specific section of his work, deploying a monographic theme with no intention of dealing with the full complexity of their production. On the other hand, an editorial positioning clearly aligned with the “aestheticist” presentation of their work, giving priority to the partial publication of it as “drawn reality” rather than offering a critical and didactic understanding of their proposals. From our personal understanding, these characteristics would be clearly at odds with the editorial line of El Croquis. So, what can an office like Dogma get out of presenting its work in a publication like El Croquis? We see it very clearly: order and depth. Through the successive exposition of delimited parts of his work, we have continually been left with the sensation of not fully understanding the global framework of their practice. This feeling has finally come to an end. If we had missed until now a profound, extensive and exhaustive publication on Dogma’s work, this is undoubtedly the issue of “El Croquis”. With its successes and its areas of uncertainty, its more polemically critical and ideological projects and others much more pragmatic and achievable, its vibrant analysis of the problems that exist in the contemporary city and its sometimes naïve responses because they have never been contrasted in the process of execution as urban elements. All of this is available to the reader in an admirable exercise in honesty rarely achieved.

Las publicaciones sobre la obra de Dogma que han aparecido hasta la fecha han tenido al menos dos características comunes. La primera de ellas, la focalización sobre un apartado muy concreto de su trabajo, desplegando un tema monográfico sin intención de abordar toda la complejidad de su producción. Por otro lado, un posicionamiento editorial claramente alineado con la presentación “esteticista” de su trabajo, dando prioridad a la publicación parcial del mismo como “realidad dibujada” por encima de ofrecer una comprensión crítica y didáctica de sus propuestas. Desde nuestro entendimiento personal, estas características se encontrarían claramente enfrentadas a la línea editorial de El Croquis. Por tanto, ¿qué le puede aportar a una oficina como Dogma presentar su trabajo en una publicación como El Croquis? Nosotros lo vemos muy claro, orden y profundidad. Mediante la sucesiva exposición de partes delimitadas de su trabajo, nos hemos quedado continuamente con la impresión de no entender del todo bien el marco global de su práctica. Esta sensación se ha terminado al fin. Si habíamos echado de menos hasta ahora una publicación profunda, extensa y exhaustiva sobre la obra de Dogma, ésta es sin duda el número de “El Croquis”. Con sus aciertos y sus áreas de incertidumbre, sus proyectos más polémicamente críticos e ideológicos y otros mucho más pragmáticos y realizables, su vibrante análisis de las problemáticas que existen en la ciudad contemporánea y sus respuestas a veces ingenuas por no haber sido nunca contrastadas en el proceso de ejecución como elementos urbanos. Todo eso se encontrará a disposición del lector expuesto en un admirable ejercicio de honestidad pocas veces alcanzado.

On the other hand, we could also ask the question in reverse: what could a publication like El Croquis possibly gain from publishing the work of an office like Dogma? If memory serves, this issue is probably the first in the long history of El Croquis that does not feature a single project built or in the process of being built. Years ago there were essential issues such as the one dedicated to the first works of OMA, Morphosis or Gigantes/Zenghelis, where the weight of unbuilt proposals was relatively important, but surely in a proportion of no more than 50%. In them we could find proposals with a high theoretical or speculative content, but also projects that had been confronted with the act of building and all the technical and legislative mechanisms that this entails. In any case, we believe that the publication of this monograph on Dogma, with its sharp critical analyses of the current context of architectural practice and its highly ideologised proposals, not to mention the articles in his own handwriting, come to consolidate the editorial line of El Croquis. A commitment that has manifested itself with resounding clarity for the professional and social ethics that have been reflected with particular intensity in recent years. Assuming, moreover, that this exception in a long trajectory can open up new horizons to be discovered that provide more accurate readings of the different complexities that make up the practice of architecture on a global scale.

Por otro lado, podríamos también formular la pregunta de manera inversa: ¿qué podría aportarle a una publicación como El Croquis publicar el trabajo de una oficina como Dogma? Si la memoria no nos falla, este número es probablemente el primero en la larga trayectoria de El Croquis que no recopila ni un solo proyecto construido o en proceso de construcción. Años atrás hubo números esenciales como el dedicado a los primeros trabajos de OMA, Morphosis o Gigantes/Zenghelis, donde el peso de las propuestas no construidas fue relativamente importante, pero seguramente en una proporción no superior a un 50%. En ellos podíamos encontrar propuestas con un alto contenido teórico o especulativo, pero también proyectos que habían sido enfrentados con el acto de construir y todos los mecanismos técnicos y legislativos que eso conlleva. En todo caso, creemos que la publicación de este monográfico sobre Dogma, con sus afilados análisis críticos sobre el contexto actual de la práctica arquitectónica y sus propuestas altamente ideologizadas, por no mencionar los artículos de su propio puño y letra, vienen a consolidar la línea editorial de El Croquis. Una apuesta que se ha manifestado con rotunda claridad por la ética profesional y social que ha quedado reflejada con especial intensidad en los últimos años. Asumiendo, además, que esta excepción en una dilatada trayectoria puede suponer una apertura a nuevos horizontes por descubrir que aporten lecturas más amplias sobre las diferentes complejidades que conforman la práctica de la arquitectura a escala mundial.

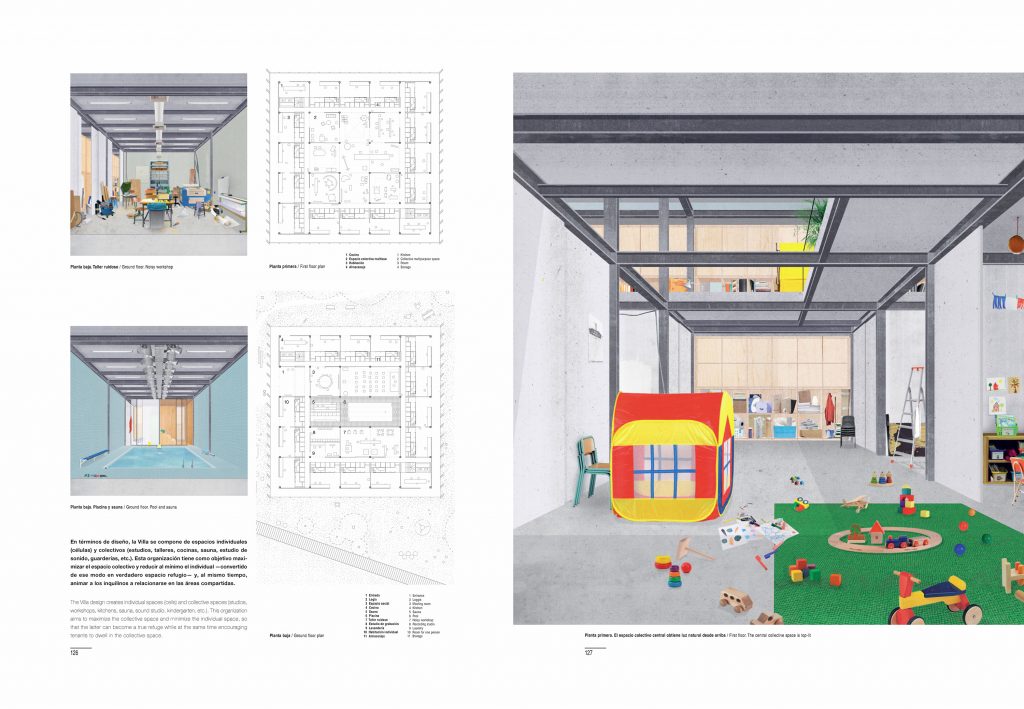

Throughout its almost 300 pages, issue 208 of “El Croquis” presents around 20 projects by Dogma, offering us the possibility of clearly tracing the two distinct stages of production we have defined above, the one centred on the urban scale and the one more focused on the search for new collective domesticities. Although we have missed some of Dogma’s projects that would have seemed particularly appropriate, the works presented here offer all the necessary clues to understand the trajectory of this office. The reader will be able to appreciate and value with delight the abysmal difference in the design approach distilled in projects as different as the first urban proposals, whose aim was no more than to reveal a critique of the post-industrial city of capitalism, and others which, while maintaining a territorial scale, focus the strength of their proposal on a sensitive approach to the landscape or to historical pre-existences in order to respond to such everyday social problems as universal accessibility.

A lo largo de sus casi 300 páginas, el número 208 de “El Croquis” nos expone alrededor de 20 proyectos de la oficina Dogma, ofreciéndonos la posibilidad de trazar con claridad las dos etapas de producción bien diferenciadas que antes hemos definido, la centrada en la escala urbana y la más focalizada en búsquedas de nuevas domesticidades colectivas. Aunque hemos echado en falta algún proyecto de Dogma que nos habría parecido especialmente oportuno, los trabajos aquí presentados ofrecen con amplitud todas las pistas necesarias para comprender la trayectoria de esta oficina. El lector podrá apreciar y valorar con deleite la diferencia abismal de planteamiento proyectual que destilan trabajos tan diferentes como las primeras propuestas urbanas, cuyo objetivo no era más que poner de manifiesto una crítica a la ciudad postindustrial del capitalismo, y otros que, manteniendo una escala también territorial, centran la fuerza de su propuesta en una sensible aproximación al paisaje o a las preexistencias históricas para dar respuesta a problemas sociales tan cotidianos como la accesibilidad universal.

As is always characteristic of “El Croquis” monographs, the in-depth presentation of the projects is accompanied by texts of critical interpretation of the works written by third parties, as well as an introductory interview that normally establishes the basic foundations for understanding the fundamentals of the work presented below. As it could not be otherwise in a monograph on Dogma, this section presents a much greater weight than usual, since, in addition to the aforementioned, three essayistic articles on Dogma will be added. We consider that this is a section to be particularly noteworthy within the exceptional overall quality of the publication. Firstly, because the interview conducted by Tatiana Bilbao and the final text by Neeraj Bhatia complement each other perfectly in their different registers to offer the keys to correctly analyse Dogma’s work. On the other hand, because the inclusion of texts by the architects whose work is exhibited is not usual, but in this case, as well as being a very welcome exception on our part, these three articles constitute some of the most intense moments of the publication. With two of them dedicated to the historical analysis of typologies and operational strategies in the field of collective housing, and a third to the arguments for their particular graphic representation, we would like to highlight in particular the article entitled “The Home at Work. A genealogy of housing for the working classes”, which brilliantly and succinctly develops Dogma’s critical positioning and its commitment to possible future scenarios in the social construction of cities based on the idea of the commons.

Como es siempre característico en las monografías de “El Croquis”, la profunda exposición de los proyectos se acompaña de textos de interpretación crítica de esta obra escritos por terceras personas, así como una entrevista introductoria que normalmente establece los cimientos básicos para conocer los fundamentos de la obra expuesta a continuación. Como no podía ser de otra manera en una monografía sobre Dogma, este apartado presenta un peso muy superior a lo habitual, ya que, a los anteriormente citados, se añadirán tres artículos ensayísticos de Dogma. Consideramos que éste es un apartado a destacar especialmente dentro de la excepcional calidad global que presenta la publicación. En primer lugar, porque la entrevista conducida por Tatiana Bilbao y el texto final de Neeraj Bhatia se complementan a la perfección en sus diferentes registros para ofrecer las claves para analizar correctamente la obra de Dogma. Por otro lado, porque la inclusión de textos propios de los arquitectos cuya obra se expone no suele ser habitual pero, en este caso, además de ser una excepción muy celebrada por nuestra parte, estos tres artículos constituyen algunos de los momentos de mayor intensidad de la publicación. Estando dos de ellos dedicados al análisis histórico de tipologías y estrategias operativas en el campo de la vivienda colectiva, y un tercero a exponer los argumentos de su particular representación gráfica, nos gustaría destacar especialmente el artículo titulado “The Home at Work. Una genealogía de la vivienda para las clases trabajadoras”, que desarrolla de manera brillante y sucinta el posicionamiento crítico de Dogma y su apuesta por posibles escenarios futuros en la construcción social de las ciudades desde la idea de lo común.

To conclude, we would like to state clearly that in the process of reading and analysing “Dogma 2002-2021. Familiar/Strange” our initial surprise at finding their work collected in a monographic issue of “El Croquis” has turned into a mood of joyful celebration. We could discuss whether the absence to date of a real confrontation with the constructed act maintains some of Dogma’s projects in a state of optimistic naivety, but it is precisely in this unprejudiced, brave, honest and sharp attack on the pre-established dogmas of the neoliberal system where the virtue of their work resides. And we join that current of optimistic resistance in celebrating the publication of this issue as what we are convinced will be one of the greatest editorial events of recent years. Because the publication of “El Croquis” is not limited to delighting us with the attractive but already hackneyed collages of Dogma, or to seducing us with accurate slogans extracted from some of the project analyses carried out by the Brussels studio. With all the rigour to which we are accustomed, it presents us with a revolutionary discourse, a critical and socially committed work with an honesty that is unusual in architectural publications so prone to show off genius. A work with its light and its dark, its triumphs, its defeats, its successes and contradictions. And all this by creating a fundamental monograph that not only presents us with the projects of one of the most influential offices of recent decades as never before, but also has the potential to become a reference work for the discipline.

Para concluir, nos gustaría exponer con claridad que en el proceso de lectura y análisis de “Dogma 2002-2021. Familiar/Extraño” nuestra sorpresa inicial por encontrar su trabajo recogido en un número monográfico de “El Croquis” se ha convertido en un estado de ánimo de gozosa celebración. Podríamos discutir si la ausencia hasta la fecha de un enfrentamiento real al acto construido mantiene alguno de los proyectos de Dogma en un estado de optimista ingenuidad, pero es precisamente en ese desprejuiciado, valiente, honesto y afilado ataque a los dogmas preestablecidos del sistema neoliberal donde reside la virtud de su obra. Y nosotros nos sumamos a esa corriente de optimismo de resistencia para celebrar la publicación de este número como lo que estamos convencidos de que será uno de los mayores acontecimientos editoriales de los últimos años. Porque la publicación de “El Croquis” no se limita a deleitarnos con los atractivos pero ya manidos collages de Dogma, o a seducirnos con certeros eslóganes extraídos de alguno de los análisis proyectuales llevados a cabo por el estudio de Bruselas. Con todo el rigor al que nos tienen acostumbrados, nos presenta un discurso revolucionario, una obra crítica y socialmente comprometida con una honestidad inusual en las publicaciones de arquitectura tan propensas al lucimiento del genio. Una obra con sus claros y sus oscuros, sus triunfos, sus derrotas, sus aciertos o contradicciones. Y todo ello creando una monografía fundamental que no sólo nos presenta como nunca hasta la fecha los proyectos de una de las oficinas más influyentes de las últimas décadas, sino que tiene el potencial de convertirse en una obra de referencia para la disciplina.