*** Article written by Alexandrina Marinova ***

Sofia. Bulgaria’s current capital and one of the most ancient cities of the old continent, where life has never stopped and always kept growing, like its own motto says: “It grows, but never gets old”.

Sofia. Actual capital búlgara y una de las ciudades más antiguas del viejo continente, donde la vida nunca ha parado y siempre ha ido creciendo, como dice su mismo lema: “Crece, pero no envejece”.

Its history began millennia ago, precisely in the II millennium BC, when the first settlement in the old center dates, just in the area of the mineral springs, where the current Mineral Central Bath is located. In this same area, during the time of the Eastern Roman Empire, on the ancient Greek city of Serdonpolis, Serdika was inaugurated, Emperor Constantin’s favorite place, to which thermal waters he often went to recover. At the end of the 2nd century, Serdikas’ thermal baths, a 4000m² complex, are built around the mineral springs.

Su historia empieza milenios atrás, precisamente en el II milenio aC, de cuando data el primer asentamiento en el antiguo centro, justamente en la zona de los manantiales minerales, donde se ubica el actual Baño Central Mineral. En esta misma área, durante la época del Imperio Romano de Oriente, sobre la antigua ciudad griega Serdonpolis, se inaugura Serdika, lugar predilecto del emperador Constantin a cuyas aguas termales acudía a menudo para recuperarse. A finales del s.II se construyen las termas de Serdika, un complejo de 4000m², expandido alrededor de los manantiales minerales.

Centuries later, during the Ottoman domination, adjacent to the central mosque Banya Bashi (work of the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan), there was a public bath (hamam) that took advantage of the same mineral waters and still used the old roman water catch.

Siglos más tarde, durante la dominación otomana, adyacente a la mezquita central Banya Bashi (obra del célebre arquitecto otomano Mimar Sinan), había un baño público(hamam) que aprovechaba las mismas aguas minerales y seguía usando la antigua captura de agua de la época romana.

After Bulgaria’s liberation, there was a need to enter the modern era and give an European aspect to the new (though historically ancient) Bulgarian capital, Sofia. Therefore, one of the first public projects proposed to a contest was the one for new Public Mineral Bath.

Tras la liberación de Bulgaria, se vio la necesidad de entrar en la época moderna y dar un aspecto europeo a la nueva (aunque antigua históricamente) capital búlgara, Sofia. Por tanto, uno de los primeros proyectos públicos propuesto a concurso fue el del Baño Mineral Público.

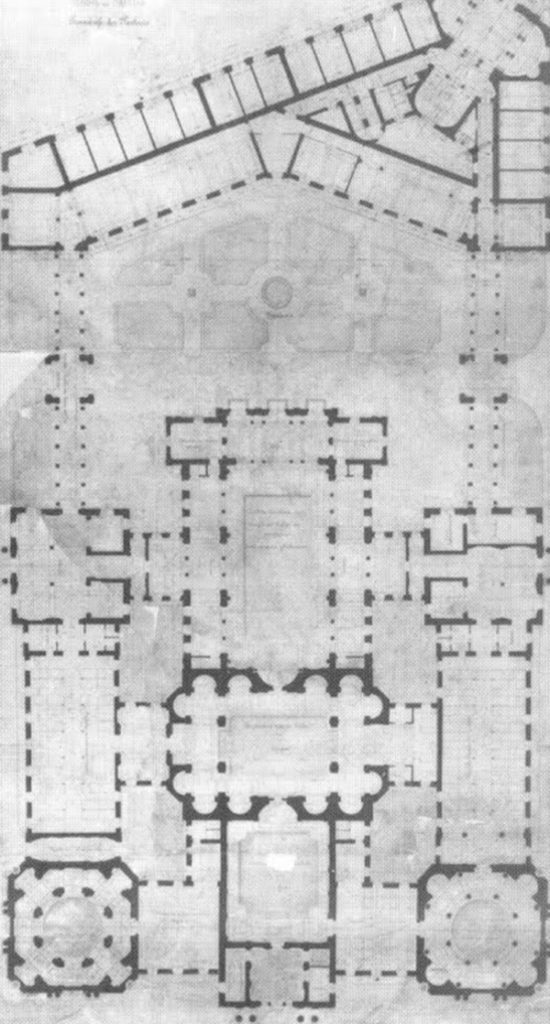

In 1889 the Austrian architect Emil von Fehrster won the international competition for Central Mineral Bath and Hotel. His proposal included a female and male public bath, also another free of charge for poor people, hydrotherapy rooms and a hotel with garden. However, as soon as the works started, it was paralyzed due to lack of money.

En 1889 el arquitecto austriaco Emil von Fehrster ganó el concurso internacional para Baño Mineral Central y Hotel. Su propuesta incluía un baño público femenino, masculino, otro gratuito para la clase baja, salas de hidroterapia y un hotel con jardín. Sin embargo, apenas empezada la obra, se paralizó por falta de dinero.

There was a need to rethink the initia lidea, removing the excessive luxury and adjusting it more to the public budget. Therefore, in 1904 the project for the current complex crystallized, created by the architects Friedrich Grünanger and Petko Momchilov. Their proposal included two baths: one small and one large, the current Central Mineral Bath.

Se vio la necesidad de repensar la idea inicial, quitándole el lujo sobrante y ajustándolo más al presupuesto público. Por tanto, en 1904 cristalizó el proyecto para el actual complejo, creado por los arquitectos Friedrich Grünanger y Petko Momchilov. Su propuesta incluía dos baños: uno pequeño y otro grande, el actual Baño Mineral Central.

In 1908 the small bathhouse, that had to temporarily meet the needs of the citizens, opened its doors, while the large one was being built. Then in 1913 the main Bath was inaugurated. A year later, in the north wing of the complex, the water treatment institute was opened.

En 1908 abrió sus puertas el baño pequeño que tenía que cumplir temporalmente las necesidades de los ciudadanos, mientras se estaba construyendo el grande, inaugurado en 1913. Un año más tarde, en el ala norte del complejo abrió el instituto de tratamiento con agua.

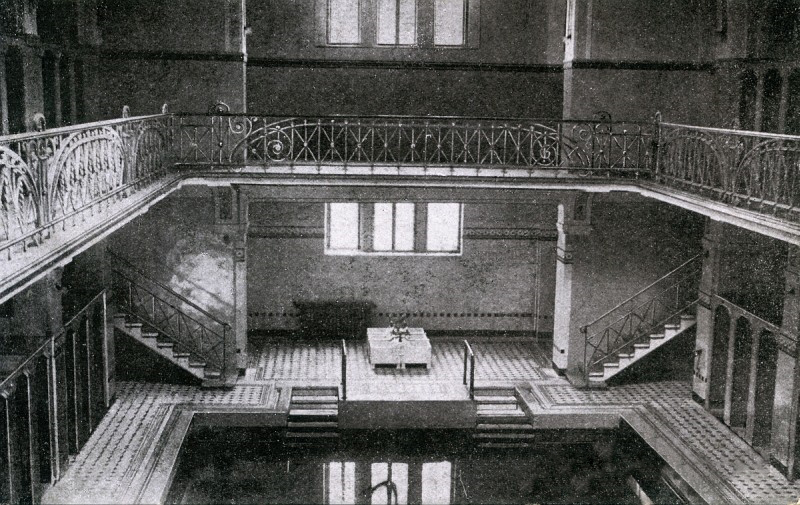

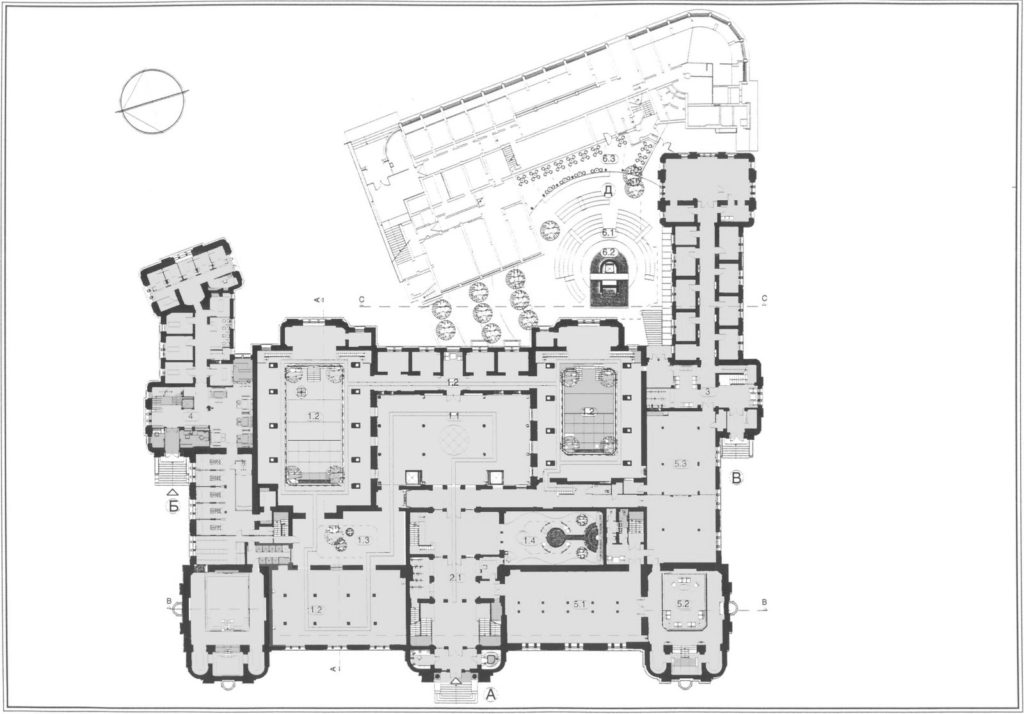

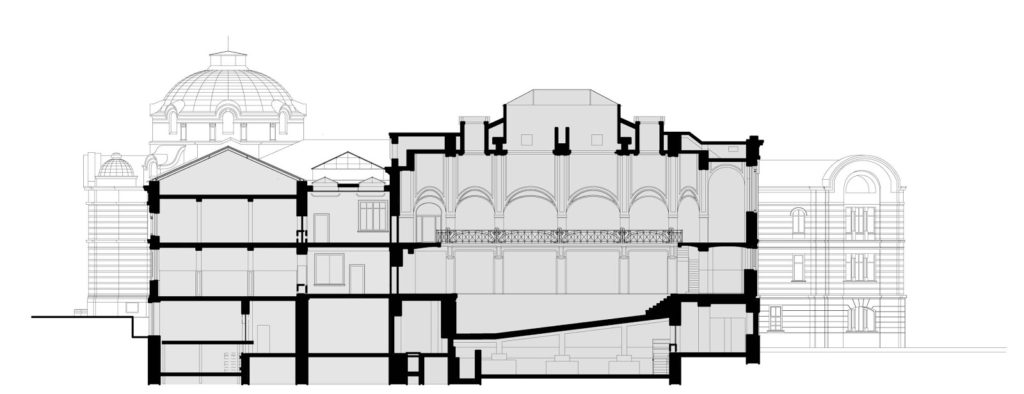

The new building of the Central Mineral Bath has almost symmetrical neo-baroque floor, whose dimensions shock at first sight, but are justified quickly given its main use and the demand of the growing capital. Its function was hygiene and treatment, meeting the requirements and latest trends of the time: from the central entrance were accessed the male facilities and from the right side entrance, the female ones. Each part had dressing rooms and rest rooms, respectively for first and second class, a large swimming pool with cold water, surrounded by a hall with showers, beds and bathtubs of marble with hot and cold running water, plus a small pool with mineral water; individual rooms with bathtubs and physiotherapy room (left side entrance); the public laundry was located next to the female room.

El nuevo edificio del Baño Mineral Central tiene una planta casi simétrica neobarroca, cuyas dimensiones sorprenden a primera vista, pero se justifican rápidamente dado su uso principal y la demanda de la creciente capital. Su función fue de higiene y tratamiento, cumpliendo con las exigencias y últimas tendencias de la época: desde la entrada central se accedía a las instalaciones masculinas y desde la entrada lateral derecha, a las femeninas.Cada parte contaba con vestuarios y salas de descanso,respectivamente para primera y segunda clase, una piscina grande para nadar con agua fría, rodeada por un hall con duchas, camas y bañeras de mármol con agua corriente fría y caliente, además una piscina pequeña con agua mineral;salas individuales con bañeras y sala de fisioterapia (entrada lateral izquierda); al lado de la sala femenina se ubicaba la lavandería pública.

On the outside, the building justifies its interior content. Its dome on the central axis marks the main entrance with its large double height lobby, and the two lateral domes, the place of the mineral water pools. On its façade, forms and details of medieval Bulgarian architecture are recreated and combined with floral and geometric majolica ornaments, work of the painter Haralampi Tachev. This strange mixture of styles – neo-Byzantine, medieval Bulgarian, Secession – was called “national romanticism”. Although two foreign architects participated in the creation of the project, the building establishes a strong relationship with local traditions and history, making clear the influence of the architect who finally carried out the construction, the Bulgarian Petko Momchilov, whose works are characterized with this style. Thus, very different from its surrounding architectural environment – the Banya Bashi Mosque, the Sofia Synagogue, other neoclassical, modern and later Baroque Stalinist buildings – the Central Mineral Bath stands out with its character and is an essential element of the image of the center of the city.

Además de convertirse en un edificio emblemático de la capital, fue uno de los sitios más frecuentados de su época. Tener un baño propio era un lujo del que pocos disponían y la gran mayoría de los ciudadanos acudía a los baños públicos y, principalmente, al Central. Solía suceder una vez a la semana, los sábados, y los visitantes se pasaban allí desde unas horas hasta el día entero. Desayunaban y comían allí, en las salas de descanso y la cantina. Ir al baño era no solo una necesidad de higiene, sino un acto social en el que surgían amistades, amor, se discutía las últimas noticias o rumores, cuestiones políticas, etc. Existía hasta un saludo que la gente se intercambiaba al salir del baño: ¡Felicidades por el baño!, siendo un acontecimiento verdaderamente importante.

In addition to becoming an emblematic building in the capital, it was one of the most frequented sites of its time. Having a bathroom was a luxury that very few people had and the vast majority of citizens went to the public baths and mainly to the Central one. This ritual used to happen once a week, on Saturday, and visitors spent there between few hours and the whole day. They had breakfast and lunch in there, at rest rooms or the canteen. Going to the bath was not only a hygiene need, but also a social act in which friendships and love arose, the latest news, rumors and political issues were discussed, etc. There was even a greeting that people exchanged when leaving the bath: “Congratulations for your bath”, since it was a truly important event.

Por fuera el edificio da justicia a su contenido interior. Su cúpula en el eje central marca la entrada principal con su gran vestíbulo de doble altura, y las dos cúpulas laterales, el lugar de las piscinas de agua mineral. En su fachada se recrean formas y detalles de la arquitectura búlgara medieval y se combinan con ornamentos florales y geométricos de mayólica, obras del pintor Haralampi Tachev. Esta extraña mezcla del estilos – neobizantino, medieval búlgaro, Secesión – fue denominada “romanticismo nacional”. Aunque en la creación del proyecto participaron dos arquitectos extranjeros, el edificio establece una fuerte relación con las tradiciones e historia locales, dejando clara la influencia del arquitecto que finalmente llevó la construcción, el búlgaro Petko Momchilov, cuyas obras se caracterizan con dicho estilo. De esta forma, muy distinto de su entorno arquitectónico circundante – la mezquita Banya Bashi, la Sinagoga de Sofia, otros edificios neoclásicos, modernos y posteriormente de estilo Barroco Stalinista – el Baño Central Mineral destaca por su carácter y es un elemento esencial de la imagen del centro de la ciudad.

At the end of the WW II, most of the center of Sofia was devastated by bombings and along with many other buildings, the small bath was completely destroyed, while the large one lost its southern wing and the mineral springs were affected.

A finales de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la mayoría del centro de Sofia fue arrasado por bombardeos y junto a muchos otros edificios, quedó completamente destruido el pequeño baño, mientras el grande perdió su ala sur y se vieron afectados los manantiales minerales.

Fortunately, the Central Bath was completely restored and continued to function until the 1980s, when its main function faded away. By then, thanks to the advances in modern housing and individual hygiene, most citizens already had their own bathroom and the ritual of going to the public one began to be a discomfort or luxury that did not find place in the accelerated daily life.

Afortunadamente, el Baño Central fue totalmente restaurado y siguió funcionando hasta los años 80, cuando su función principal se fue desvaneciendo. Para entonces, gracias a los avances de las viviendas modernas y la higiene individual, la mayoría de los ciudadanos disponía ya de baño propio y el ritual de ir al público empezó a convertirse en una incomodidad o lujo que quedaba cada vez más lejos de la acelerada vida cotidiana.

With the fall of Socialism, the Bath closed and along with many other public buildings, fell into the deepest oblivion and abandonment. In 1998 was made the decision to revive it, but changing its original function, by turning it into a museum. Currently, half of the building houses the Museum of Sofia, unfortunately very little of the original interior could be preserved, only the cast iron decorations of the main hall and the staircases and a few Viennese mosaic pavements can be seen. The rest of the building, including the large pools, invisible to museum visitors, is destined for a SPA, yet to be done. Until it is realized, the mineral waters, carriers of the millenary tradition, can only be exploited in the public fountains of the Bath’s Square. Nowadays, when passing through the center and the Banski Square, these fountains and the building, deprived of their original function, are the only testimonies that recall of the ancient tradition and purpose of this place Sofia owes its beginnings to

Con la caída del Socialismo, el Baño cerró y junto a muchos otros edificios públicos, cayo en el más profundo olvido y abandono. En 1998 se tomó la decisión de revivirlo, pero cambiando su función original, convirtiéndolo en museo. Actualmente la mitad del edificio alberga el Museo de Sofia. Lamentablemente pudo conservarse muy poco del interior original, y solo pueden apreciarse las decoraciones de fundición del hall principal y de las escaleras y unos pocos pavimentos de mosaicos vieneses. El resto del edificio, incluidas las piscinas grandes, invisibles para los visitantes del museo, está destinado a un SPA, aún por hacer. Hasta que se éste se realice, las aguas minerales, portadoras de la tradición milenaria, solo se pueden aprovechar en las fuentes públicas de la plaza del Baño. Al pasar hoy por el centro y la plaza Banski, dichas fuentes y el edificio, privado de su función original, son los únicos testimonios que recuerdan la antigua tradición y propósito de este lugar al que,sin duda ninguna, debe sus inicios Sofia.

Photos by Alexandrina Marinova

Interior Photos