INTERVIEW IN ENGLISH WITH THE ARCHITECT IGOR VALIKEVSKY (Entrevista en español más abajo)

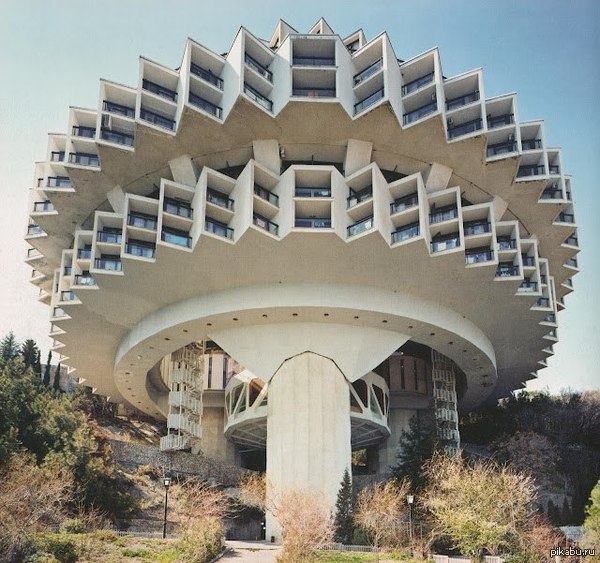

Robin Monotti: In the West, when we think of the icons of late Soviet architecture, two projects come to mind: the Ministry of Highways in Tbilisi, Georgia, by George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania (1975), and the Druzhba Sanatorium in Crimea, which you designed (1985). Chakhava defined his approach as the Space City method, which involved lifting the building off the ground and allowing nature to flow below it. This had its origin in the Aero-City or futurist city on stilts drawings of Lazar Khidekel of the 1920s. Was this your intention too to lift the building off the ground in order to allow nature to flow under the building?

Igor Vasilevsky: This issue goes deeper and is more serious – it’s about the relationship of building to the environment. In my opinion nature is the primary element of composition. The steps to solve this problem are basically two. First: create a large-scale environment with greenery and man, include a people container in the natural landscape. Second: attempt to physically preserve nature, separating the building from the ground. This is typical for structures on complex geological conditions and terrain. That is why “Druzhba” was “flying”. We had already experimented with this in Crimea. It is possible to come to such a decision once you have lived your entire life going through the application of standard projects throughout the country: the club-restaurant, sleeping accommodation, medical centre and so on.

RM: Was the natural landscape of the Crimean shoreline an important contextual consideration in the design of the building as a whole?

IV: Yes, certainly. The defining aspects were the conservation of the natural environment and at the same time the creation of optimum conditions for each part of the project, divided into two components. One: the use of daylight and visual connections with nature, primarily for the bedrooms, dining room, swimming pool, without visual spoilers: roofs in front of windows, ventilation ducts and so on. Two: the social part that is operational in the evening without sunlight. This essential position influences the entire structure.

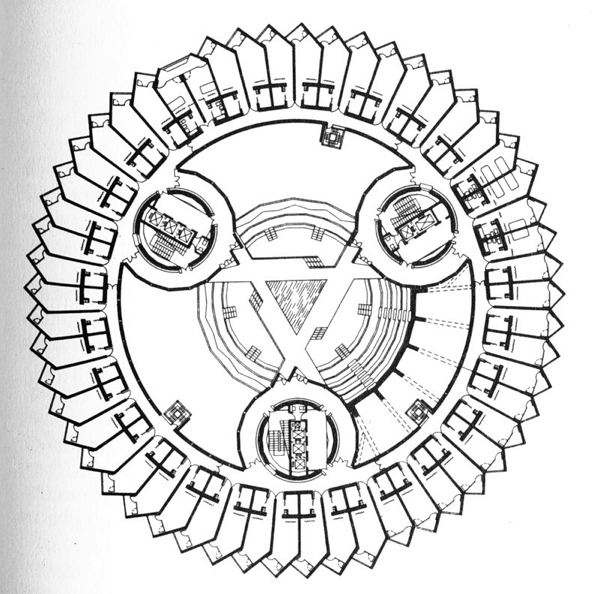

Looking from the outside, it was not easy to achieve the internal acoustic separation criteria without any compromise on any component of the program. A massive bedrooms block is always at odds with the public. In this new concept, which can be called “mono-block”, the sleeping area turns into a boundary enclosing the public areas and is positioned on the outer perimeter, where a person inside their bedroom is left alone with nature which was preserved. The public part, physically occupying the centre, becomes the dominant feature of the composition

Sometime in the late seventies, when studying the methods of construction of monolithic buildings, in particular a method of supporting slabs from reinforced concrete cores for rigidity, it struck me like lightning: why do these elements of rigidity – circulation towers, not support the entire building? This touchstone was accepted by the town-planning council in Crimea. It was a square plan, with courtyards, lifted on four pillars. The town-planning board adopted the proposal with enthusiasm, as one of the new directions in the developments of areas with sloping terrains, landslides and so on.

So if we talk about what happened in the eighties – when there was a requirement for the construction of “Druzhba”, we had already formed a conceptual approach to building on sites with a steep topography, to detach the object from the ground.

RM: I am interested in the idea that the circular plan may have been inspired by the wave patterns made by a drop falling into a surface of water. In 1972 Tarkovsky’s film Solaris was released. It featured a shot of a circular space ship with circular corridors, floating above the ocean of Solaris. In 1986 the space station MIR was sent into Orbit. Was the Soviet space program a conscious influence in your work?

IV: That idea was already spreading within the office as we were designing the building. After construction of the project some legends started spreading. It was initially presented as a “time-machine”. Soon after though it was associated with a “flying saucer” having landed on the coast.

Of critical importance was the understanding of the architect and engineer. Kancheli based the basic solution of this problem on the example of the project “Sunrise” near the Nikitsky botanical garden. Square in plan, it had design flaws – cantilevers which meet at right angles – the weakest points. We decided to avoid them and make a round plan, keeping the ideology of that project.

The site setting was extremely complex: a fault, seismic zone 8, landslides. Therefore, it was necessary to choose the most stable system. It turned out to be a “stool” on three legs where all supports have an even load. This was the basis of the structure.

Everything in the building – floors, transverse, longitudinal walls are all doing structural work. The constructive solution where there are no bearing and borne elements- is brilliant. The result was a huge five-storey monolithic honeycomb beam.

Extract of interview with Igor Vasilevsky by Robin Monotti Graziadei and Nikolai Vassiliev that took place at the Central House of the Architect in Moscow on May of 2016. English translation by Robin Motti Graziadei. You can find the rest of the interview here:

ENTREVISTA EN ESPAÑOL CON EL ARQUITECTO IGOR VALIKEVSKY

Robin Monotti: En Occidente, cuando pensamos en los iconos del último periodo de la arquitectura soviética, hay dos proyectos que nos vienen a la mente: El ministerio de transporte de Tbilisi en Georgia proyectado por George Chakhava y Zurab Jalaghania (1975), y el Sanatorio Druzhba en Crimea, el cual tu proyectaste en 1985. Chakhava definió su propuesta como un método de ciudad espacial, en el cual propuso levantar el edificio del suelo y permitir que la naturaleza fluyera debajo de él. Esta aproximación tenía su origen en los dibujos que creó Lazar Khidekel en la década de 1920 sobre la ciudad aeroepsacial o ciudad futurista. Cuál fue tu intención en elevar el edificio del suelo para permitir que la naturaleza creciera debajo de él?

Igor Vasilevsky: La propuesta es más seria y tiene implicaciones más serias – es una relación del edificio con su entorno ya que personalmente creo que la naturaleza es el primer elemento compositivo. Los pasos para resolver este problema son básicamente dos: en primer lugar crear un ambiente a gran escala relacionando la naturaleza con el ser humano e incluyendo espacios para los individuos dentro en ambientes naturales. Esto es común en estructuras sobre condiciones geológicas complejas. Esta es la razón por la que el “Druzhba” volaba. Anteriormente ya habíamos experimentado estructuras similares en Crimea y es posible tomar ciertas decisiones una vez que has trabajado toda tu vida con proyectos similares por todo el país tales como el club restaurante, alojamientos de vivienda, centros médicos, etc.

RM: Era la costa natural de Crimea una consideración importante en el diseño del edificio?

IV: Ciertamente sí. Los aspectos que definieron el proyecto fueron por un lado la conservación del entorno natural y al mismo tiempo la creación de condiciones óptimas para cada parte del proyecto, siendo éstas divididas en dos componentes. En primer lugar el uso de la luz natural y las conexiones visuales con la naturaleza, principalmente las habitaciones, el salón y la piscina sin obstrucciones visuales tales como terrazas enfrente de las habitaciones, conductos de ventilación, etc. En segundo lugar el factor solar es el funcionamiento del proyecto por las noches sin luz natural. Estos factores influenciaron de manera esencial toda la estructura.

Desde el interior no fue sencillo conseguir un criterio de aislamiento acústico sin perjudicar ninguno de los componentes del programa. Un conjunto de dormitorios siempre entra en conflicto con cualquier programa público. El concepto del proyecto, al que podríamos llamar “monobloque”, el área de dormir aparece como un límite que encierra las áreas públicas y se sitúa en el perímetro exterior, donde una persona dentro de su dormitorio se queda sola con la naturaleza que conserva. La parte pública, que ocupa físicamente el centro, se convierte compositivamente en un lugar dominante.

En algún momento al final de la década de 1970, cuando estábamos estudiando los métodos de construcción en edificios monolíticos y, particularmente, un método de losas estructurales con núcleos de hormigón armado como elementos que pudieran rigidizar la estructura, una pregunta me vino a la mente, ¿Por qué no hacemos que tales elementos – las torres de circulación – soporten todo el edificio? Esta idea fue aceptada por el Departamento de Planeamiento de Crimea. Era una planta cuadrada sostenida sobre cuatro pilares. El entusiasmo por parte del Departamento de Planeamiento se basaba en la nueva dirección que tomamos para desarrollar proyectos en áreas escarpadas y con topografías abruptas.

Entonces cuando en los años 80 cuando tuvimos que empezar con el proyecto de “Druzhba” ya teníamos una acercamiento conceptual para la construcción de proyectos en áreas con fuertes pendientes separando el objeto del propio terreno.15

RM: Me interesa particularmente el hecho de que la planta circular pudiera estar inspirada por las ondas que se crean cuando una gota cae sobre una superficie de agua. En 1972, se estrenó la película Solaris de Tarkovsky y en ella aparecía una nave espacial con galerías circulares flotando sobre el océano de Solaris. Más tarde, en 1986, la estación espacial MIR se puso en órbita. ¿Tuvo el programa espacial soviético alguna influencia de forma consciente en tu propio trabajo?

IV: Esa idea estaba ya asentada dentro de la oficina cuando estábamos diseñando el edificio y durante su construcción se comenzaron a lanzar diferentes rumos: al principio se la conocía como la “máquina del tiempo” y más tarde empezar a estar asociada con un platillo volador que había aterrizado en la costa.

No obstante, su importancia está en entender la relación entre su arquitectura e ingeniería. Kancheli basó la solución al problema estructural con el ejemplo del proyecto “Sunrise” cerca del jardín botánico Nikitsky. En el diseño con una planta cuadrada, los voladizos terminaban en ángulo recto, siendo los puntos más débiles de la estructura. Para evitarlo, redondeamos la planta manteniendo su concepto anterior.

El lugar donde se iba a construir era extremadamente complejo con una falla considerada zona sísmica nivel 8 y varios corrimientos de tierra. Por tanto, era necesario elegir el sistema estructural más eficiente. Resulta que acabó siendo “una banqueta” de tres piernas donde cada soporte recibe el mismo número de cargas. Esta fue el concepto estructural.

Todos los elementos del proyecto tienen tales como suelos y muros longitudinales y transversales recogen parte de la carga estructural. La solución constructiva, donde no hay elementos de carga ni arriostramientos es brillante. El resultado fue una gran cercha monolítica de cinco pisos.

Extracto de la entrevista con Igor Vasilevsky realizada por Robin Monotti Graziadei y Nikolai Vassiliev que se realizó en la casa central del arquitecto en Mosco en Mayo del 2016. La traducción al inglés ha sido realizada por Robin Motti Graziadei y la traducción al español ha sido realizada por Hidden Architecture para esta misma web. Se puede encontrar el resto de la entrevista en inglés en este enlace.