This article is part of the [Beyond Los Andes], a personal project curated by Germán Andrés Chacón that explores the approach of modernity and the following tendencies on Chilean architecture through the analysis of some of its works, seeking to reveal the features that define its specific nature.

Este artículo es parte de la serie [Beyond Los Andes] , comisariada por Germán Andrés Chacón en la que se estudia el enfoque de la modernidad y las posteriores tendencias en la arquitectura chilena a través del análisis de algunas de sus obras, tratando de revelar los aspectos que definen su carácter específico.

***

“The building for the Cooperative of Electric Services of Chillán, Copelec, constitutes on behalf of its quality and density, an exceptional case in the scene of modern architecture in Chile. However, it does not result from the work of an established professional office. It embodies a theoretical reflection effort as well as a pursuit for an alternative way to face the practise of architecture”.

“El edificio para la Cooperativa de Servicios Eléctricos de Chillán, Copelec, constituye por su calidad y densidad, un caso excepcional en el panorama de la arquitectura moderna en Chile. No es, sin embargo, resultado del trabajo de una oficina profesional establecida. Es la encarnación de un esfuerzo de reflexión teórica a la vez que la búsqueda de un modo alternativo de plantearse frente al ejercicio de la arquitectura”.

Fernando Pérez Oyarzun, “COPELEC: La Física y la Carne”, in “Los hechos de la arquitectura”, Fernando Pérez, Alejandro Aravena y José Quintanilla, Ediciones ARQ, Chile (1999)

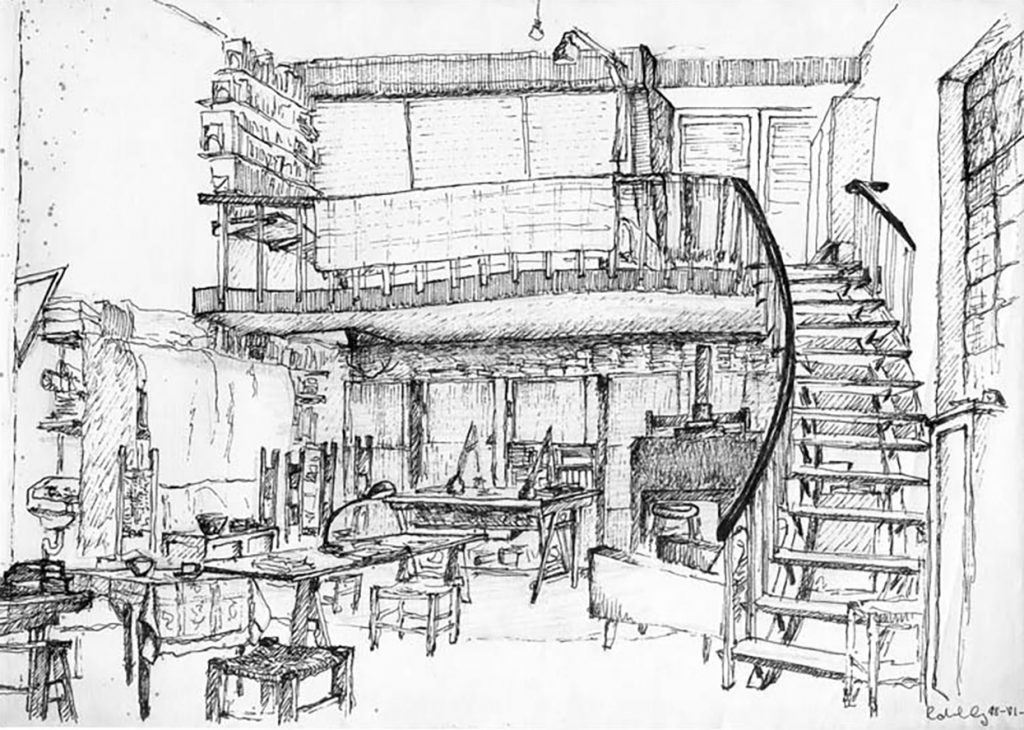

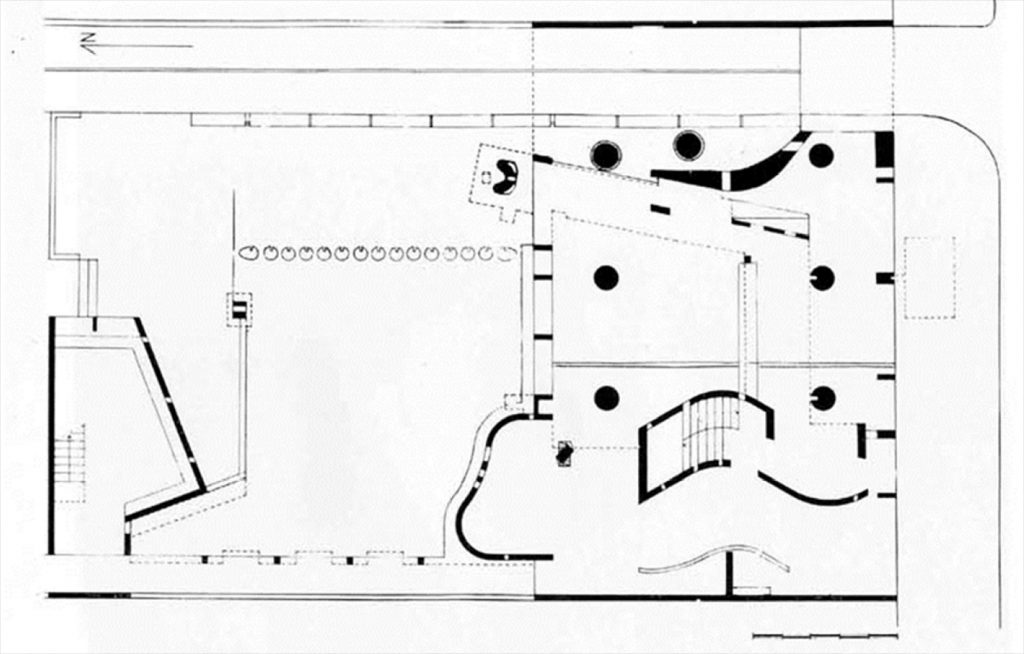

Juan Borchers’s studio drawn by Rodrigo de la Cruz B.

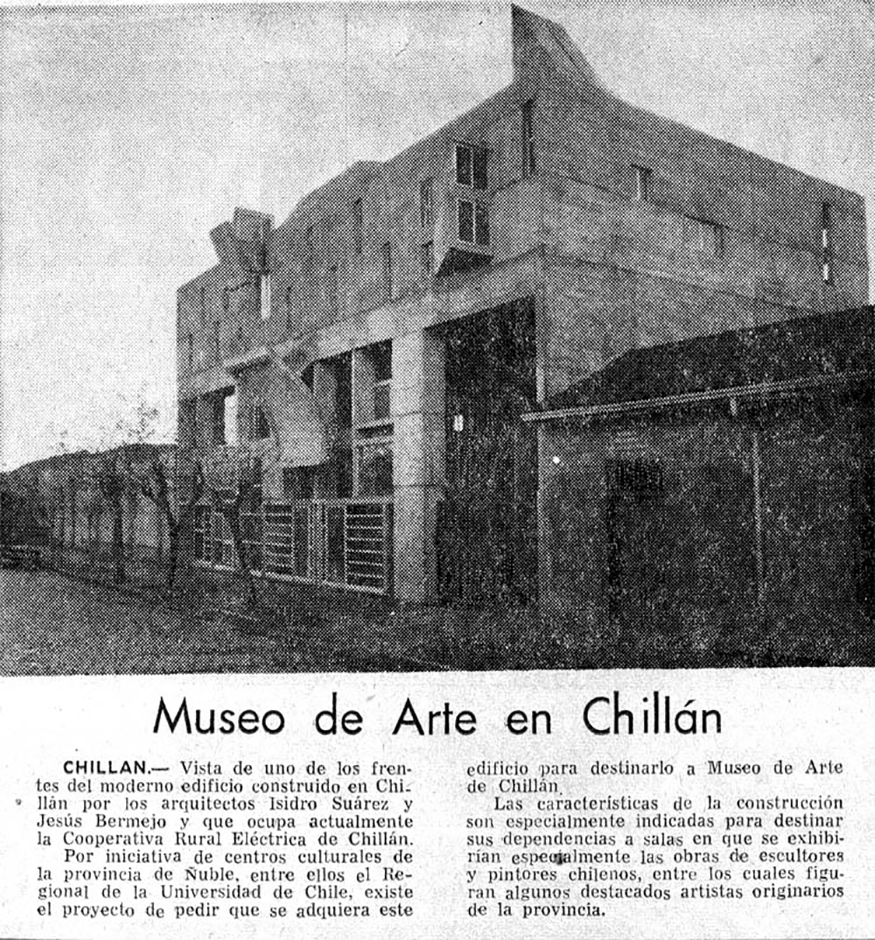

In 1939 an earthquake with its epicenter in Chillán caused severe damages in some cities in the south of Chile. Their recovery provided an unprecedented opportunity to test the principles of modern architecture. This even came to attract the attention of Le Corbusier, who offered to design the reconstruction plans of Chillán, Concepción and Talcahuano. That potential commission to the Suisse architect was never performed and the rebuilding plan finally carried out –the one by Luis Muñoz Maluschka–, maintained the conservative concepts of closed block and continuous facade. Around seven hundred constructions were built on the five years following the earthquake.

En 1939 un terremoto con su epicentro en Chillán provocó graves daños en varias ciudades del sur de Chile. Su recuperación ofreció una oportunidad inédita para poner a prueba los principios de la arquitectura moderna. Ésta llegó incluso a atraer la atención de Le Corbusier, quien se ofreció para hacer los planes de reconstrucción de Chillán, Concepción y Talcahuano. Ese potencial encargo al arquitecto suizo no se llegó a realizar, y el plan de reconstrucción de Chillán llevado a cabo finalmente –el de Luis Muñoz Maluschka–, mantuvo los conservadores conceptos de manzana cerrada y fachada continua. Alrededor de setecientas construcciones fueron levantadas en los cinco años posteriores al sismo.

In those days, Chilean architects –trained in the Beaux Arts style– worked mainly in the traditional way, and neoclassic and Art Deco architecture prevailed in the city. They had initially adopted the modern language as another style added to the eclectic game they played. It was during those years of fervent building activity –after Chillan’s earthquake– when some of them started to work operating entirely with the principles of the International Style in works such as the Complex of Municipal Buildings and the Fire Department of Chillán, both by Ricardo Müller.

Los arquitectos chilenos de entonces –educados en el estilo Beaux Arts– trabajaban mayoritariamente de manera tradicional, y la arquitectura neoclásica y Art Decó predominaba en la ciudad. El lenguaje moderno había sido inicialmente adoptado por éstos como un estilo más, que añadían al juego eclecticista que practicaban. Fue durante estos años de ferviente actividad edificatoria –tras el terremoto de Chillán– cuando algunos de ellos comenzaron a trabajar aplicando integralmente los principios del Estilo Internacional en obras como el Conjunto de Edificios Municipales y el Cuerpo de Bomberos de Chillán, ambos de Ricardo Müller.

COPELEC’s Building is outstanding for breaking with that rationalistic tendency settled for years, through an expressive and personal design by Juan Borchers’s studio.

El edificio de la COPELEC es destacable por romper con esa tendencia racionalista asentada durante años, mediante un expresivo y personal diseño firmado por el taller de Juan Borchers.

This architect started his studies in Universidad de Chile, where his reformist position on the education plans led him to be expelled. The following years he travelled –mostly around Europe–, drawing scrupulously and comparing multiple works of universal value. He focused on studying the physic condition of architecture, excluding its social, political and cultural aspects. That superficiality in his observations revealed properties of architecture hidden to those who contextualize it. His particular way to look at constructions and his knowledge of works by contemporary and classic authors gave him a syncretic vision, which combines principles and forms from different intellectual currents, shaping a heterogeneously modern character. He wrote then some Manifiestos which would delay to be published, such as Institución Arquitectónica (Editorial Andrés Bello, 1968) and Meta-Arquitectura (Editorial Mathesis, 1975). When he returned, he created a workshop in Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, where he taught since 1974, developing together with his mentees and students a particular approach to the profession.

Este arquitecto comenzó sus estudios en la Universidad de Chile, donde su postura reformista en cuanto a los planes de enseñanza de la profesión le llevó a ser expulsado. Los años siguientes se dedicó a viajar –principalmente por Europa–, dibujando escrupulosamente y comparando múltiples obras de valor universal. Centró su atención en el estudio de la condición física de la arquitectura, dejando al margen sus aspectos sociales, políticos o culturales. Esa superficialidad en sus observaciones desvelaba propiedades de la arquitectura ocultas para quien la contextualiza. Su particular manera de mirar las construcciones y su conocimiento de obras tanto de autores contemporáneos como clásicos le dieron una visión sincrética, en la que se combinaban principios y formas de distintas corrientes de pensamiento, conformando un carácter heterogéneamente moderno. Escribió entonces varios manifiestos que tardarían años en publicarse, como Institución Arquitectónica (Editorial Andrés Bello, 1968) y Meta-Arquitectura (Editorial Mathesis, 1975). A su vuelta, formó un taller en la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, donde ejerció la docencia desde 1974, desarrollando junto con sus discípulos y alumnos un particular acercamiento a la profesión.

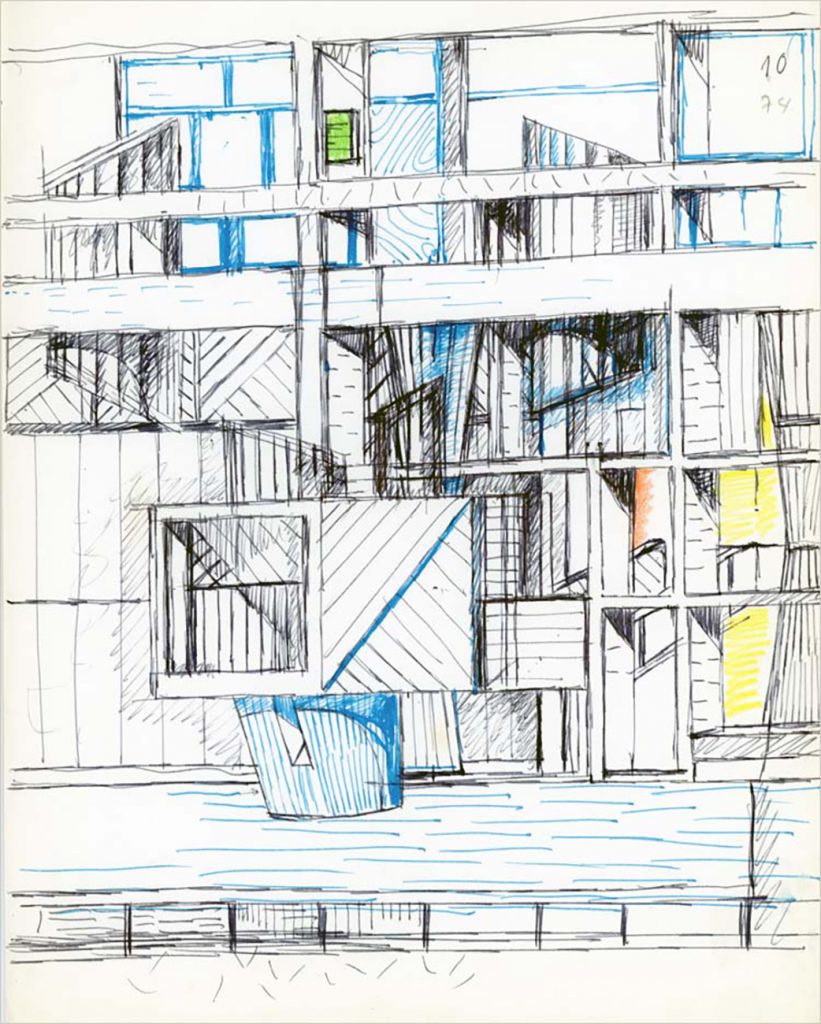

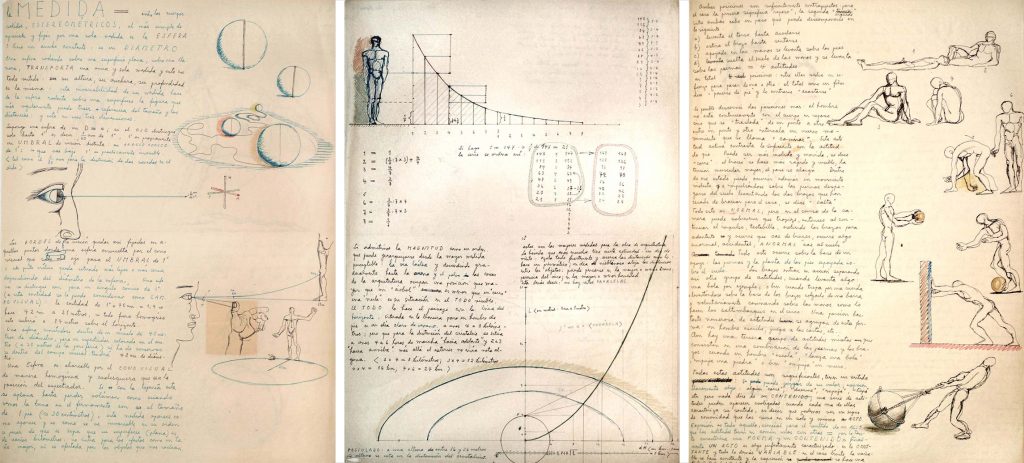

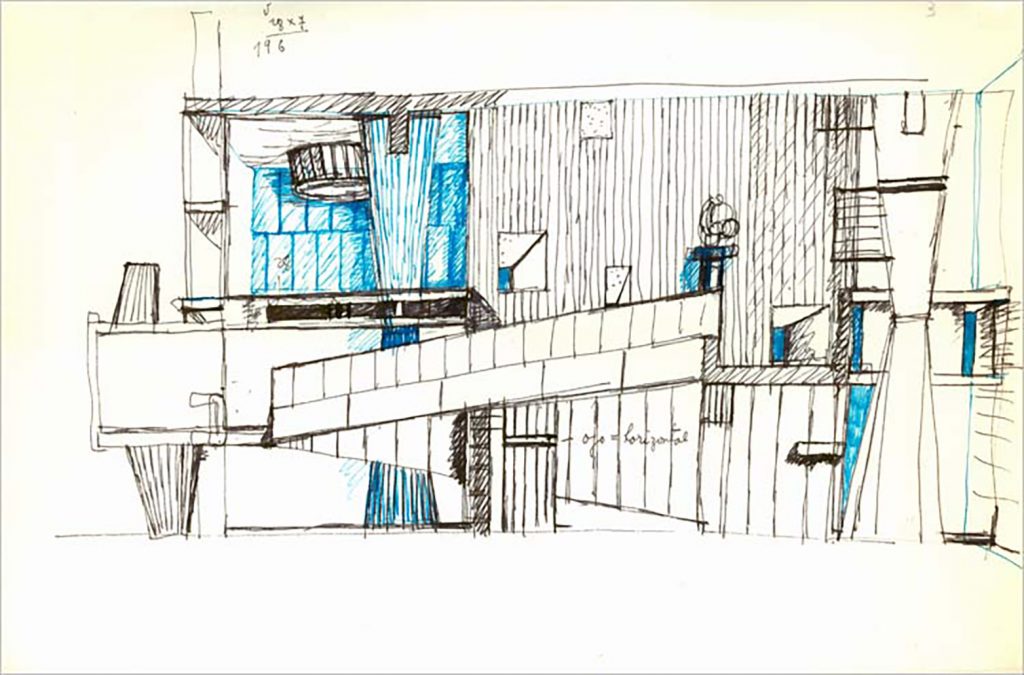

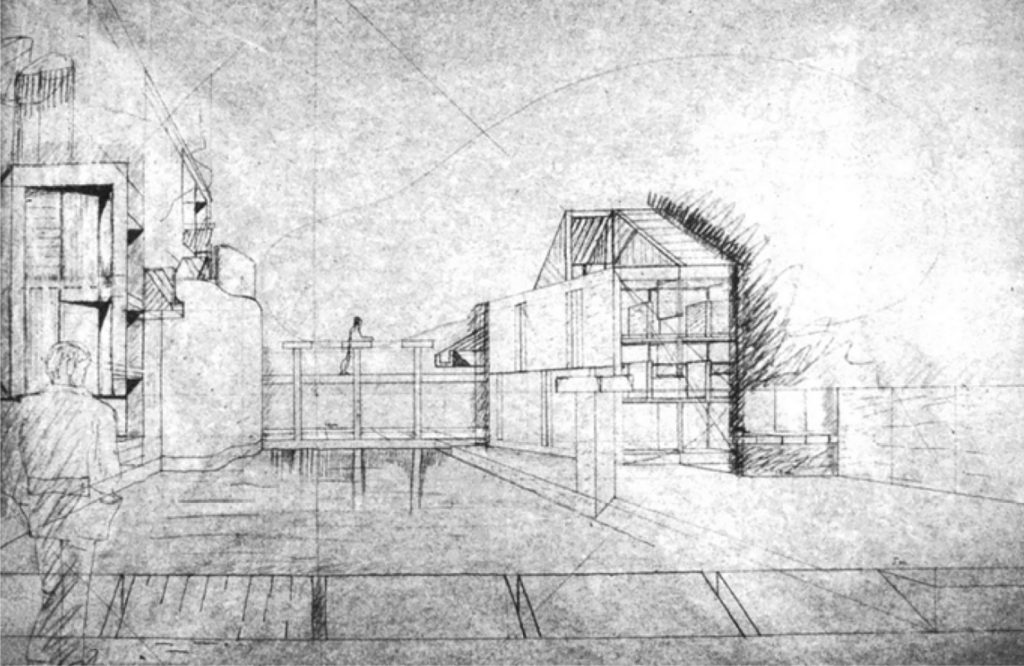

Juan Borchers understood architecture as an intersection between space and time, incorporating the temporal dimension to the understanding of every object. He upheld that the real and specific material of architecture consists in the human acts to which it gives shape. Representation was his principal tool to apprehend and study the surrounding world. Thereupon, he criticised the use of parallel projection due to its incapacity to express and perform experience. He used, as an alternative method, a geometric system based on the summation of perspectives that together enable the arrangement of the complete object. He wrote, drew and designed with the aim of depicting the architectural language of substantial immobility, which he defined as the plastic manifestation of movements and actions.

Juan Borchers entendió la arquitectura como una intersección entre el espacio y el tiempo, incorporando la dimensión temporal a la comprensión de todo objeto. Defendió que el material real y específico de la arquitectura reside en los actos humanos a los que da forma. La representación fue su principal herramienta de aprehensión y estudio del mundo que le rodeaba. Criticó el uso de la proyección paralela por su incapacidad para expresar e interpretar la experiencia. Empleó como alternativa un sistema geométrico basado en el sumatorio de perspectivas que permiten construir el total del objeto. Escribió, dibujó y proyectó con el objetivo de representar el lenguaje arquitectónico de la inmovilidad substancial, que definió como la manifestación plástica de movimientos y acciones.

COPELEC’s Building commission was to Juan Borchers –who had mainly worked in single-family house projects so far– one of the few opportunities he had to materialize years of studies on proportions and geometry, particularly the dimensional system later shown in Meta-Arquitectura. Edmundo Vélez, general manager of the cooperative back then, got in touch with the architects through Isidro Suárez’s brother. The affinity with the clients –who “wanted light, color and great originality” – played a fundamental role.

El encargo del edificio de la COPELEC fue para Juan Borchers –que hasta entonces había realizado principalmente proyectos de viviendas unifamiliares– una de las muy pocas oportunidades que tuvo para materializar años de estudio en torno a las proporciones y la geometría, particularmente el sistema dimensional posteriormente expuesto en Meta-Arquitectura. Edmundo Vélez, director general de la cooperativa en aquel momento, contactó con los arquitectos a través del hermano de Isidro Suárez. La afinidad con los clientes –que “querían luz, sol, color y gran originalidad” –jugó un papel fundamental.

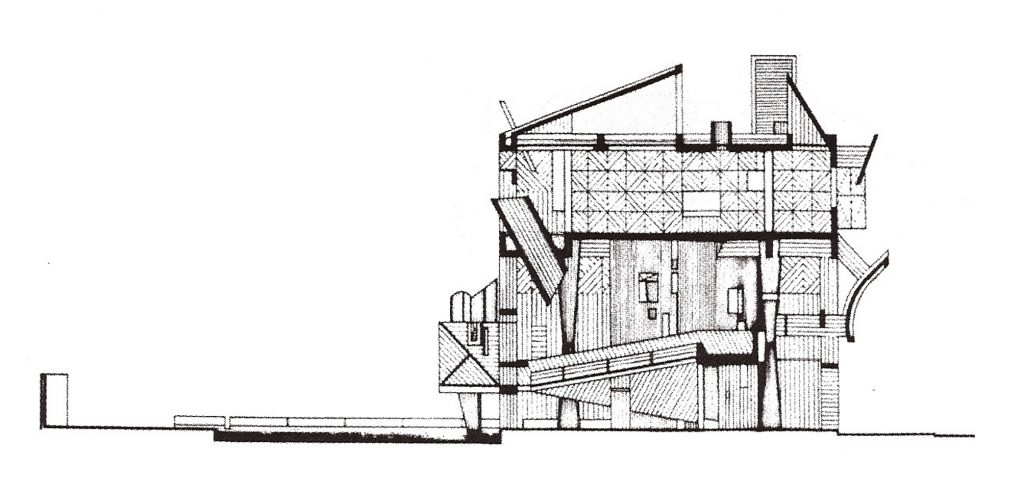

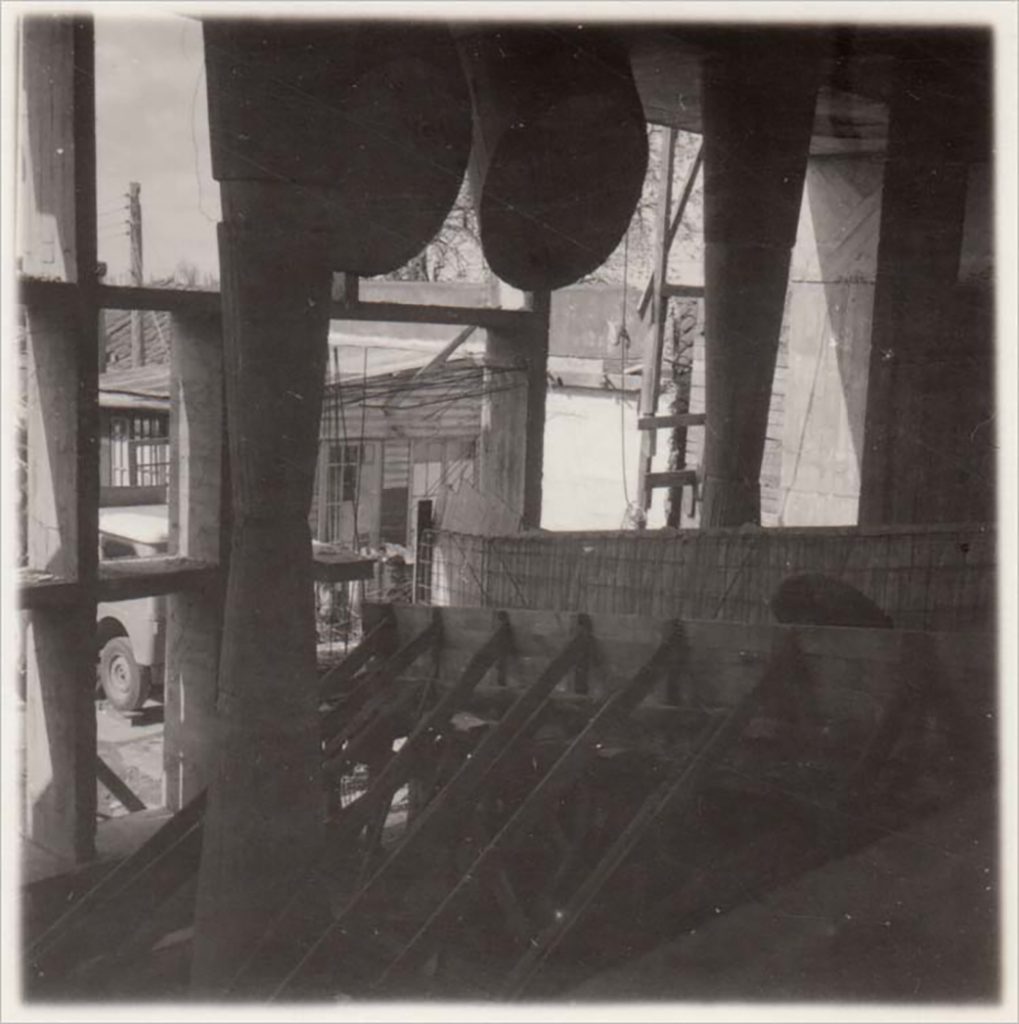

“The studio’s collaborators worked on the general distribution of the project in daily postal communication with Juan Borchers, who was at that time in Europe. From there, he introduced modifications that would become fundamental in its later development and that were recorded in these letters. He reduced the materiality of the building to reinforced concrete and defined a layout and a system to control its dimensions from its entirety to detail. He proposed to work on each element as if it was a project in itself, capable of owning its independent development running until the works had already started. He modified the absorption direction of seismic stresses, providing more transparency in the longitudinal axis of the piece and introduced the ramp as the element that sews the project vertically. When the works started, Borchers returned to Chile to manage them. “

“Los colaboradores del taller trabajaron en la distribución general del proyecto en constante comunicación por carta con Borchers, quien se encontraba en ese momento en Europa. Desde allí, éste introdujo modificaciones que serían fundamentales para su posterior desarrollo y que quedaron registradas en esa correspondencia. Redujo la materialidad del edificio al hormigón armado y definió un trazado y control dimensional del mismo desde la totalidad al detalle. Propuso el trabajo de cada elemento del edificio como un proyecto en sí mismo, capaz de poseer un desarrollo propio y abierto hasta comenzada la ejecución material de la obra. Modificó la dirección de absorción de los esfuerzos sísmicos proporcionando mayor transparencia en el sentido longitudinal la pieza e introdujo la rampa como elemento que ata el proyecto en vertical. Al comienzo de la obra, Borchers volvió a Chile para su supervisión. “

Jesús Bermejo interviewed by Carolina Marcos in La Discusión newspaper (may 19th, 2013)

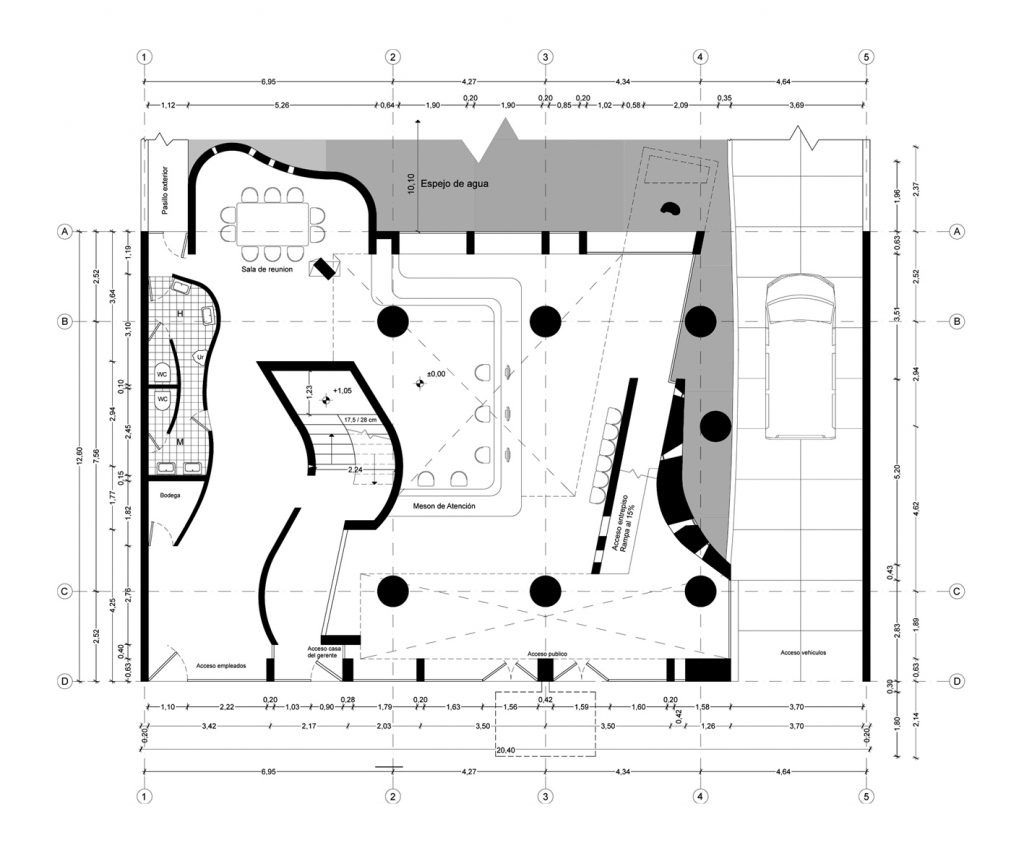

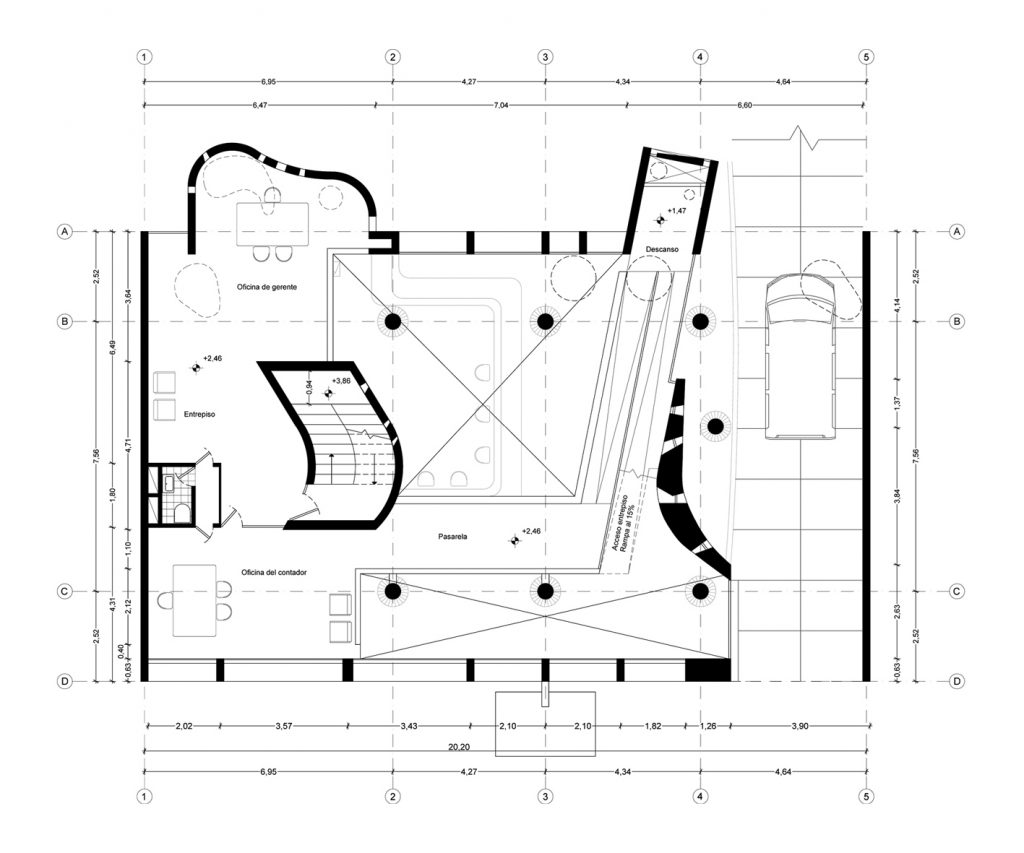

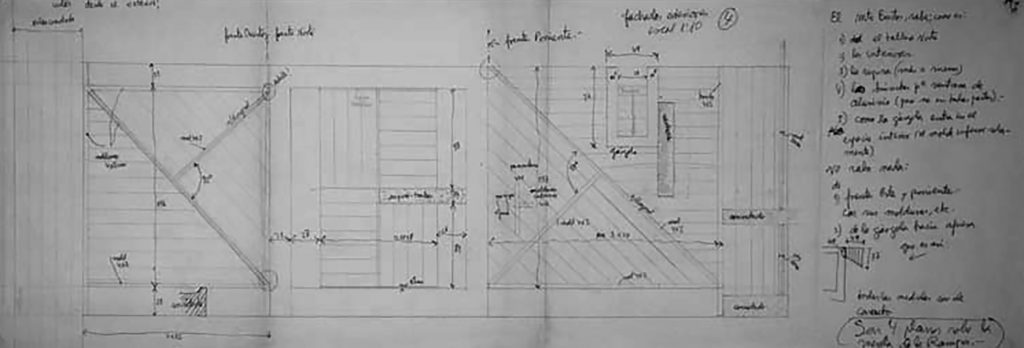

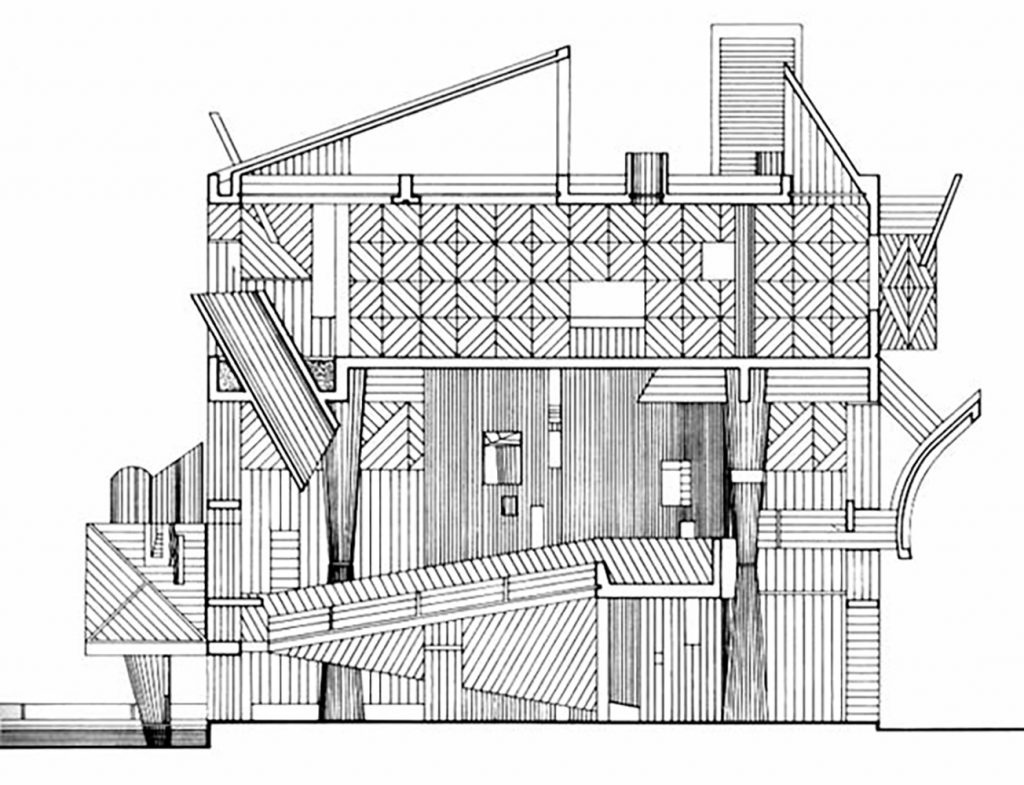

The project consists of one cubic volume of 21 x 10,50 x 12,60 meters inscribed in the initial seven centimeters module that Borchers established as the base of the measures system. This piece is positioned on the block’s perimeter, opening a court to the interior and allowing the conformation of a continuous facade together with the adjacent buildings which, in fact, still has not come to consolidate.

El proyecto consiste en un único volumen cúbico de 21 x 10,50 x 12,60 metros que se inscribe en el módulo inicial de siete centímetros que Borchers estableció como base del sistema de medidas. Esta pieza se posiciona en el perímetro de la manzana, abriendo un patio en el interior y permitiendo la formación de una fachada continua junto con las edificaciones adyacentes que, de hecho, aún no se ha llegado a consolidar.

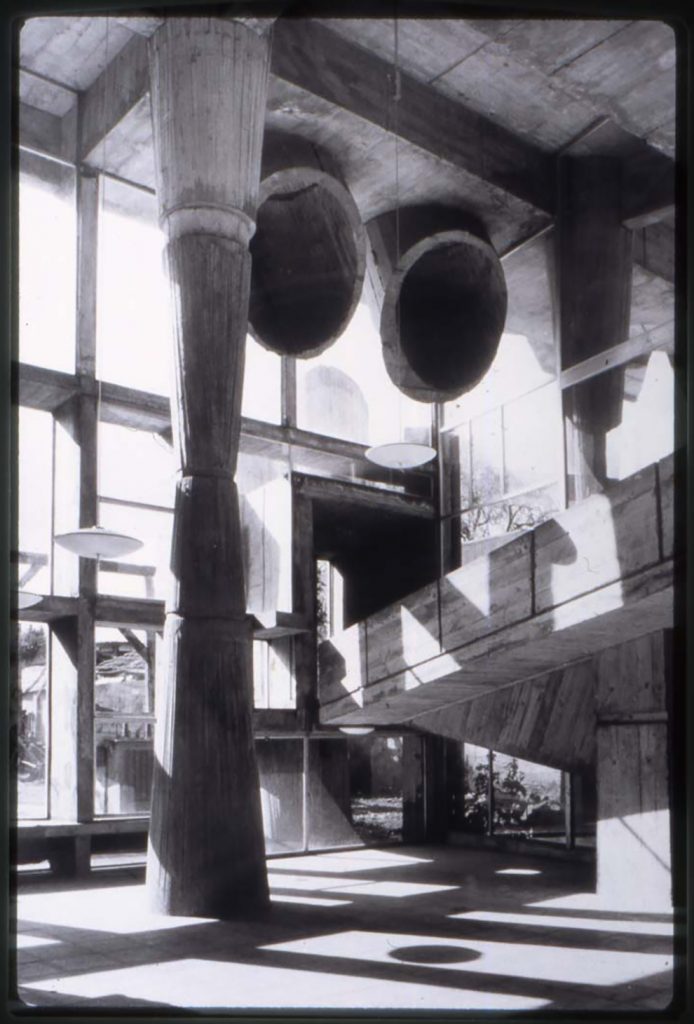

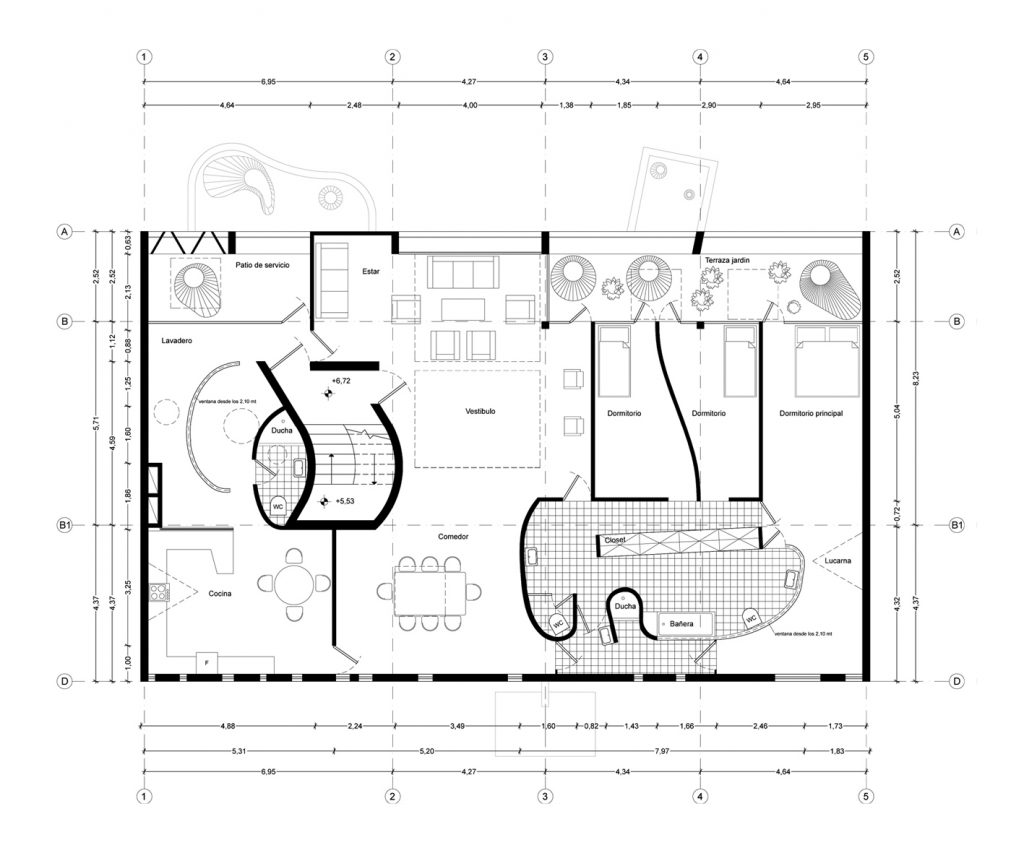

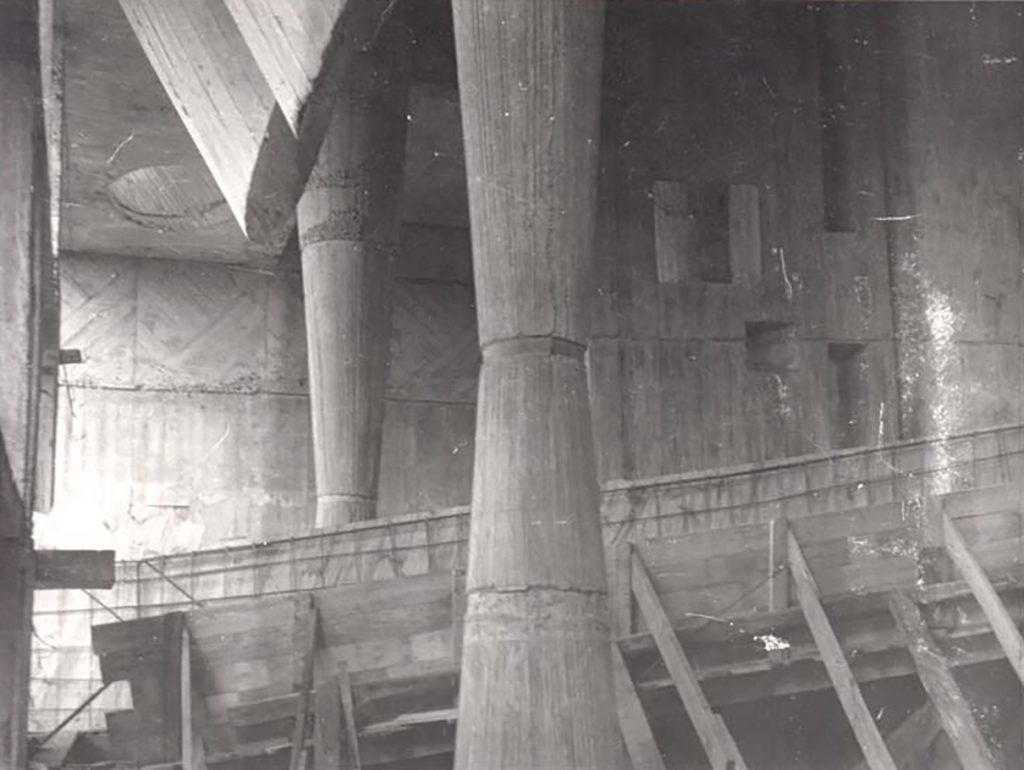

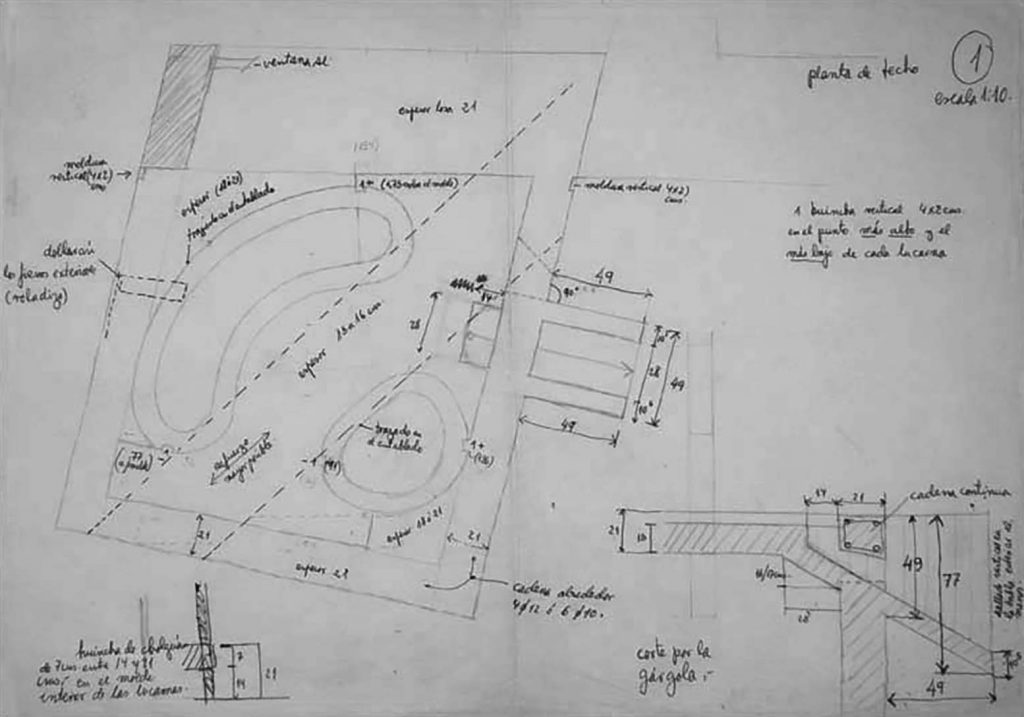

Its 630 sqm surface hosts the Electric Cooperative’s offices on the ground and first floors, and a house for the company’s director on the second floor. The offices are set by a double height space occupied by seven pillars shaped as doubled and inverted cones in a possible reinterpretation of the classical atrium. Other spaces of smaller size are attached to it through delimitation or connection elements: the ramp, the walkway, the stairs and the curved walls. Between these, unexpected visual and plastic relations appear so that, like in cubist art, the items are composed in different ways when the space is toured. The ramp, which landing is an annexed volume hanging from the south facade, connects the customer service space with the private area. This element reveals the duality present on the project between modular rigidity and compositive freedom. It even goes beyond the cubic volume which encloses the building. The director’s house is distributed around a terrace and a large bath area delimited by curved partitions that play with diverse intimacy levels and, in its center, a big closet is peculiarly placed.

Sus 630 m2 de superficie albergan las oficinas de la Cooperativa Eléctrica en planta baja y primera, y una vivienda para el director de la compañía en planta segunda. Las oficinas se componen de un espacio de doble altura ocupado por siete pilares de doble cono invertido –una posible reinterpretación del atrio clásico– al que se vinculan otros espacios de menor tamaño mediante elementos que actúan como delimitadores y conectores: la rampa, la pasarela, las escaleras y los muros curvos. Entre estos aparecen inesperadas relaciones visuales y plásticas de modo que, como en el arte cubista, los elementos se van componiendo de diversas maneras al recorrerlo. La rampa, cuyo rellano es un volumen anexo colgado del alzado sur, conecta el espacio de atención al público con la zona privada. Este elemento evidencia la dualidad existente en el proyecto entre rigidez modular y libertad compositiva, llegando a traspasar el volumen cúbico que forma el edificio. La vivienda del director está distribuida alrededor de una terraza y una amplia área de baño delimitada por tabiques curvos que juegan con grados de intimidad y, en cuyo centro, se posiciona peculiarmente un gran armario.

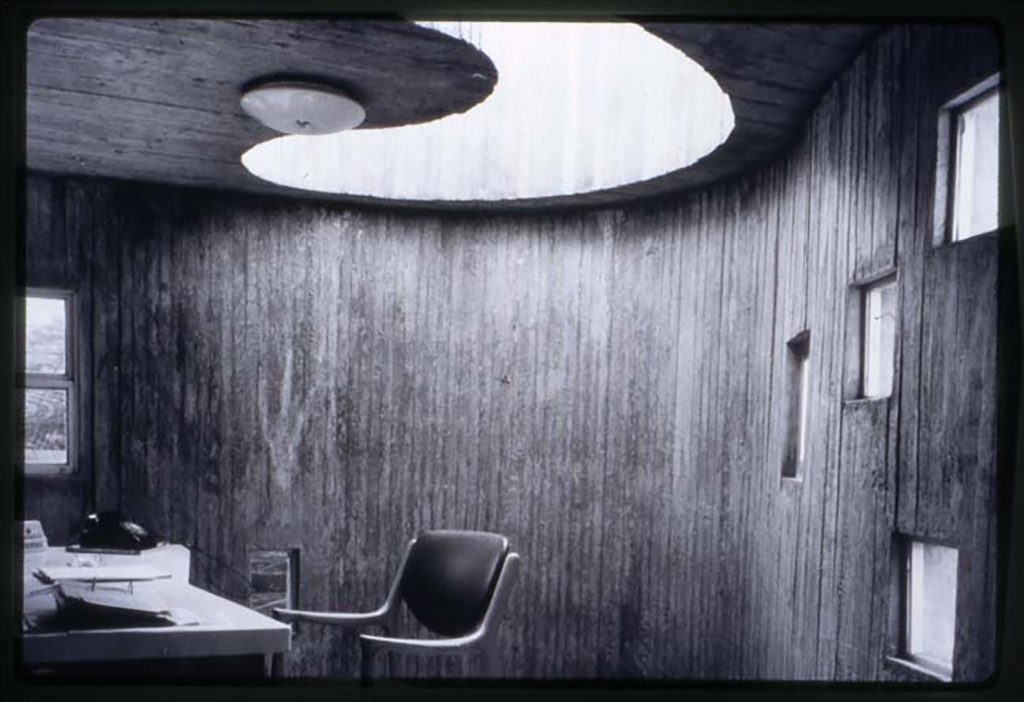

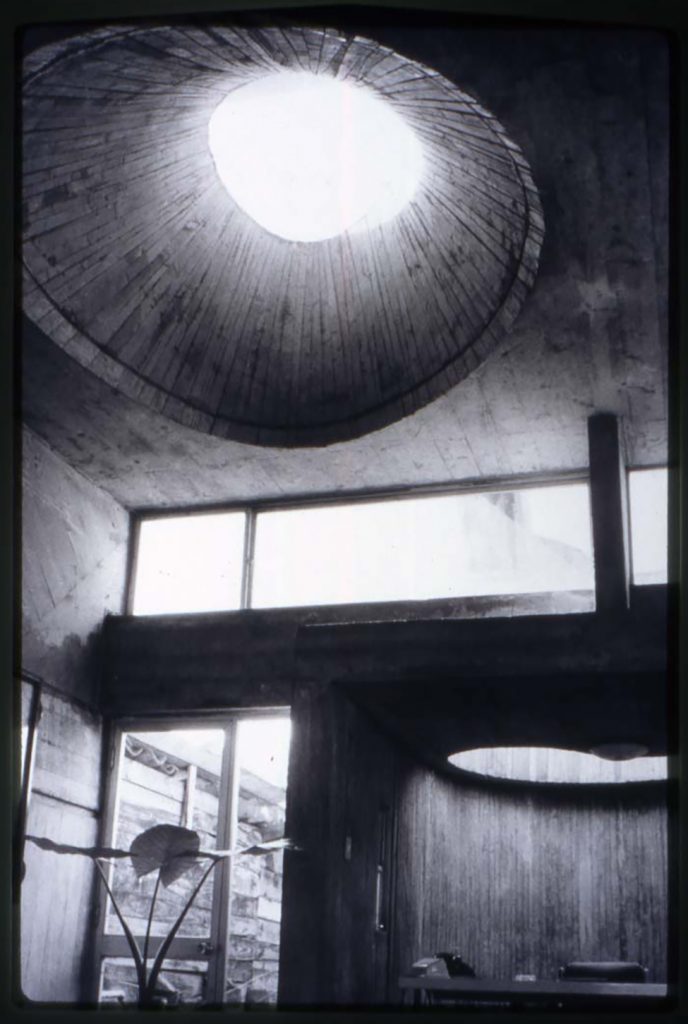

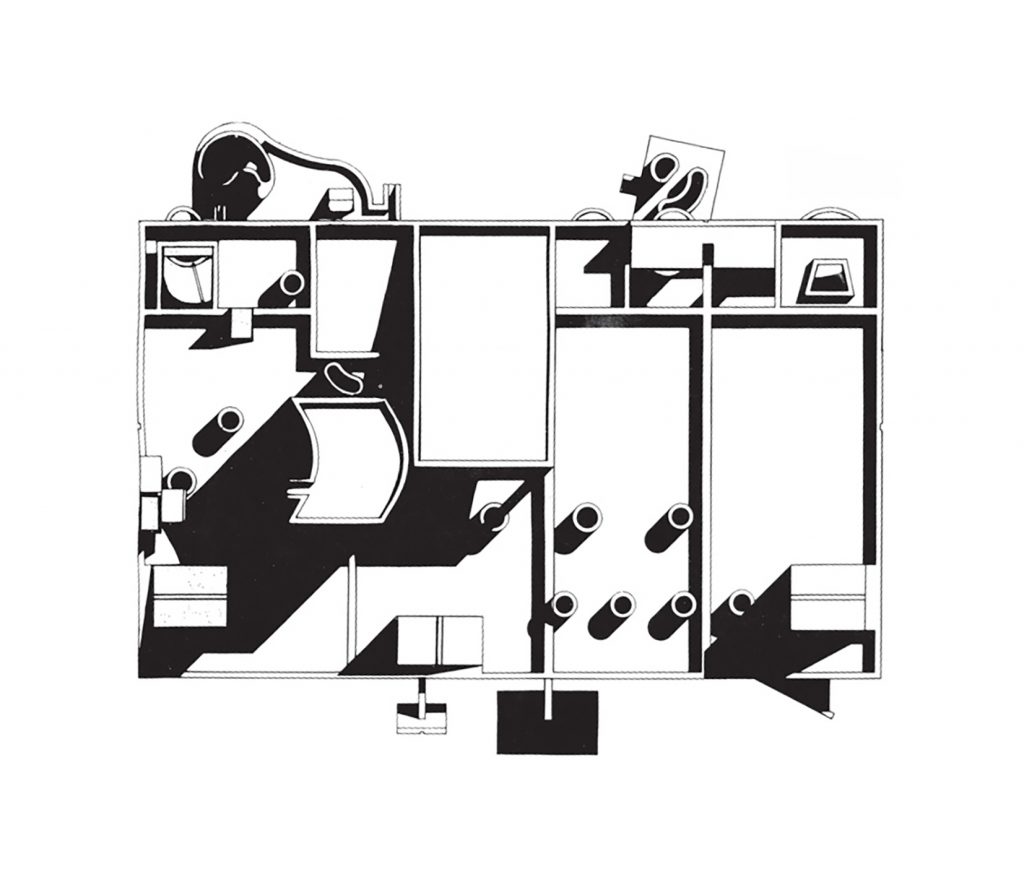

The harnessing of natural light, which for Borchers was the fourth dimension of architecture, is an essential issue of the project. Thus, its facades and rooftop are heterogeneously designed to filter, catch, disperse or reflect it.

El aprovechamiento de la luz natural, que para Borchers era la cuarta dimensión de la arquitectura, es un tema fundamental del proyecto, cuyas fachadas y cubierta están heterogéneamente diseñadas para filtrarla, atraparla, dispersarla o reflejarla.

The south elevation –which faces a public road– is set by a doble height open and transparent entrance area over which a tight entablature, that accommodates the private use and in which a discontinuous series of svelte vains, is placed. The north facade –opened to the court– protects the interior from direct sunlight setting back the different glass planes with regard to a brise-soleil looking concrete framework which includes two light cannons and two massive projected bodies, one cubic and the other curved. The design of the east and west elevations is more austere and contained because of their border condition. Understood as the fifth facade, the upper terrace is densely occupied by skylights, chimneys and some inclined planes of diverse orientations and sizes, which appear over the cornice either from the street and from the court. The envelope design reveals the willingness to attend to the specific conditions of the site, outcoming surprisingly appropriate to environmental aspects.

La fachada sur –que enfrenta una vía pública– se compone de un área de acceso abierta y transparente de doble altura sobre la que se posiciona un hermético entablamento que alberga el uso privado y en el que aparece una discontinua serie de esbeltos vanos. La fachada norte –abierta al patio– se protege de la luz solar directa retranqueando sus distintos planos de vidrio respecto a un entramado de hormigón tipo brise-soleil que incluye dos cañones de luz y dos cuerpos salientes masivos, uno cúbico y otro curvo. Las actuaciones en las fachadas este y oeste son más austeras y contenidas al tratarse de muros medianeros. Entendida como una quinta fachada, la terraza superior está densamente ocupada por claraboyas, chimeneas y varios planos inclinados de diversas orientaciones y tamaños que asoman tras la cornisa tanto desde la calle como desde el patio. El diseño de la envolvente evidencia la preocupación por responder a las condiciones específicas del lugar, resultando sorprendentemente adecuado a los factores medioambientales.

The building construction took place between 1962 and 1965, being left unfinished in default of executing the water mirror of the court, the doorman’s house, the walkway which provided access to it, and the internal the partitions of the director’s house. The second floor remained diaphanous only interrupted by the expressive cylindric skylights which go through its slab.

La construcción del edificio se realizó entre los años 1962 y 1965, quedando inacabada a falta de ejecutar el espejo de agua del patio, la casa del portero, la pasarela que le daba acceso y la tabiquería de la vivienda del director. La segunda planta quedó como un espacio diáfano tan solo interrumpido por los expresivos lucernarios cilíndricos que atraviesan su forjado.

The compositive strength of the building results from the exhaustive work it took and the high density of intentions present in each element. The rough appearance of the reinforced concrete –with a meticulous geometry in the formwork placing– gives the building a handcrafted and purely plastic character which recalls the latest shapes of Le Corbusier, slightly emphasized. The modular system, which generates a sensorial experience based on the scalar ambiguity, must not be interpreted “as an aesthetical control mechanism, but a code that articulates the architectural events and the acts proposed by the building”

La fuerza compositiva del conjunto resulta del trabajo exhaustivo y la alta densidad de intenciones presentes en cada elemento. El aspecto rugoso del hormigón armado –con una cuidada geometría en el posicionamiento de los encofrados– le da a la obra un carácter artesanal y puramente plástico que recuerda a las formas del último Le Corbusier, algo enfatizadas. El sistema de modulación, que genera una experiencia sensorial basada en la ambigüedad escalar, no debe interpretarse “como un mecanismo de control estético, sino como un código que articula los hechos arquitectónicos y los actos propuestos por la obra”.

Fernando Pérez Oyarzun, “Ortodoxia / Heterodoxia”. Published in Casabella 650 (1997)

Declared National Historical Monument in 2007, this work –one of the Chilean modern architecture referents– has been exhibited in expositions such as “Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980” at the MoMA (Nueva York, 2015) or “Desvíos de la deriva” at Reina Sofía Museum (Madrid, 2010). Nevertheless, it is still awaiting to be refurbished and host the Cultural Center and Electric Museum of Chillán, since this was announced in 2013. For that purpose, COPELEC suggested the construction of the small percentage of the original project which was never executed. Jesús Bermejo, the only living architect of those who worked on its design, volunteered to supervise this exciting project, that unfortunately is still just an unaccomplished beautiful idea.

Declarada Monumento Histórico Nacional en 2007, esta obra –referente de la arquitectura moderna chilena– ha sido exhibida en exposiciones como “Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980” en el MoMA (Nueva York, 2015) o “Desvíos de la deriva” en el Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid, 2010). A pesar de ello, sigue pendiente de ser reformada para albergar el Centro Cultural y Museo Eléctrico de Chillán, desde que esto se anunciara en 2013. Para este fin la COPELEC se planteó la construcción del pequeño porcentaje del proyecto original que nunca llegó a ejecutarse. Jesús Bermejo, único arquitecto vivo de los que trabajaron en su diseño, se ofreció a supervisar este estimulante proyecto que lamentablemente es hasta hoy tan solo una bonita idea.

All images and plans, excepting the ones copyrighted, are from:

– Archivo de Originales. FADEU. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

***

Germán Andrés Chacón is Architect by Higher Technical School of Architecture of Alcalá (ETSAUAH) and Madrid (ETSAM). Former student in Lisboa and Santiago de Chile, currently working in Madrid. He is interested in the theoretical issues of architecture and their effect on the built environment as well as focused on collective housing design. @gandreschacon (Instagram)