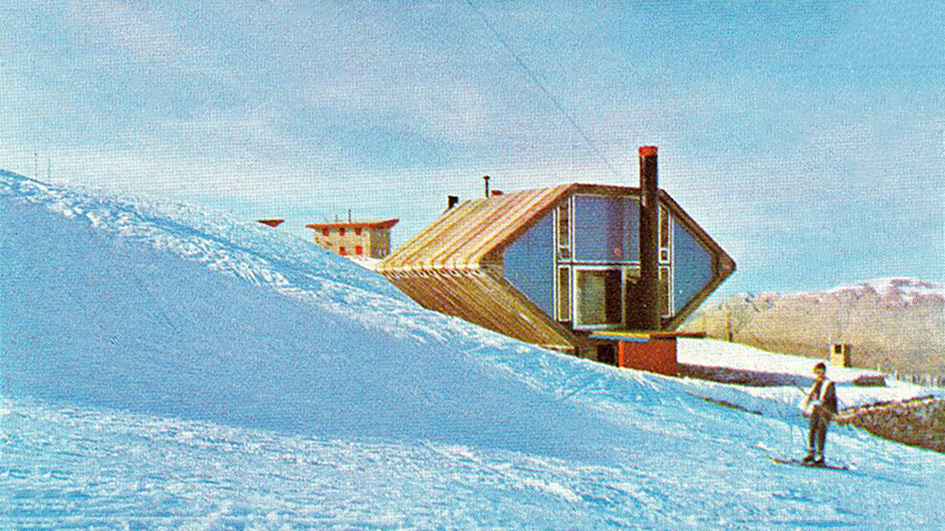

Designed in the early 1970’s by Lebanese architect Maurice Hindié, this mountain chalet was constructed as a home-refuge for the architect and his family during ski season. Being the first prefabricated house built in Lebanon, the chalet stood out in three aspects: First, for the choice of its material; second, for the imagination of its form; and third, for its exemplary integration into its site.

Proyectado a principios de la década de 1970 por el arquitecto libanés Maurice Hindié, este chalé de montaña fue construido como un hogar-refugio para el arquitecto y su familia durante la temporada de esquí. Siendo la primera casa prefabricada construida en Líbano, el chalet destacaba en tres aspectos: por sus materiales forma; y tercero, y su integración en el solar.

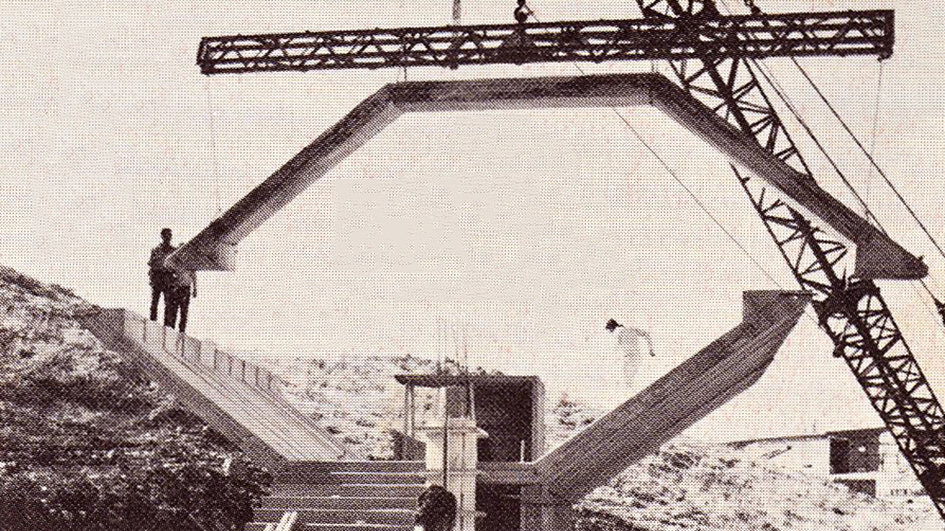

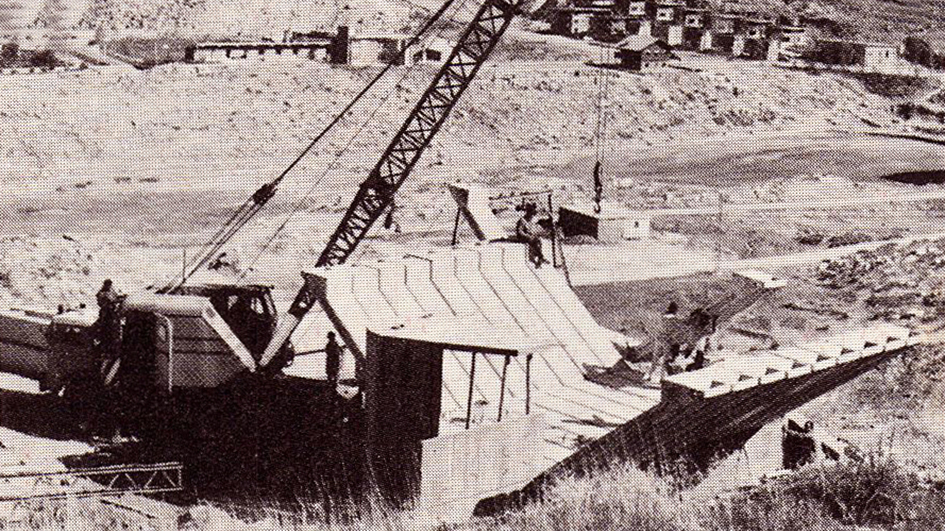

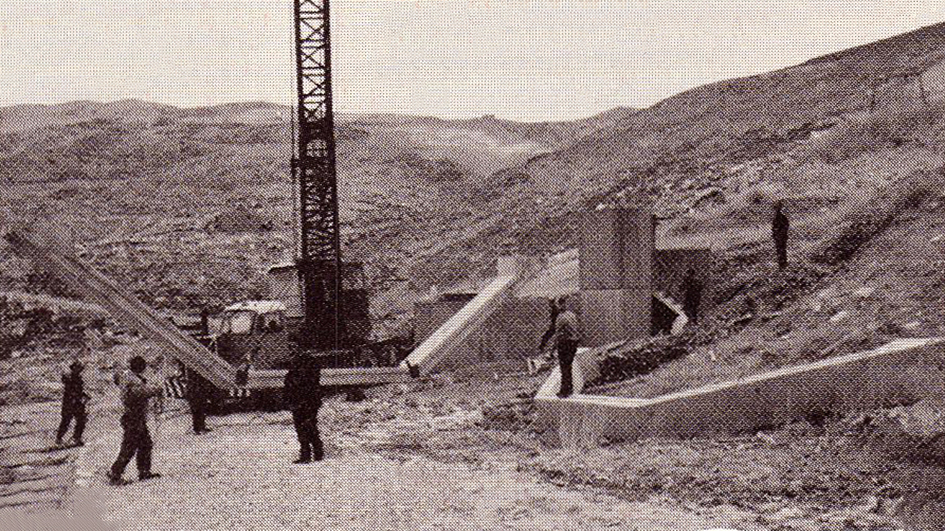

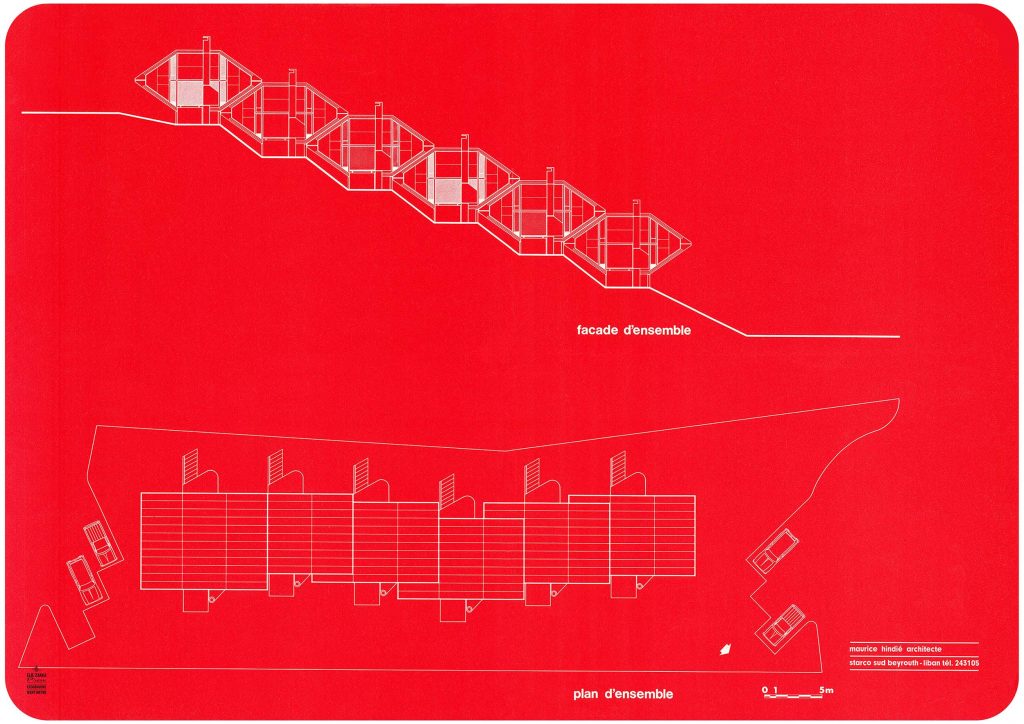

Located in Faraya, a village in the Mount of Lebanon widely known for skiing, Hindié’s original intention was to construct this cabin in a group of six following the slope of the mountain. The six hexagonal units, pre-cast in factory and assembled on site, would therefore follow the descending slope of the terrain with an overlap of one-third; hence, allowing for a maximum liberation of the land and creating a cascading composition as if the units were sliding one above the other in an image of movement through which the landscape has been formed over time.

Ubicada en Faraya, un pueblo en el Monte del Líbano ampliamente conocido por su estación de esquí, la intención original de Hindié era construir esta cabaña junto a otras seis, siguiendo la pendiente del solar, solapándose un tercio cada una con la siguiente y por tanto liberar el máximo terreno y crear una composición en cascada, como si las unidades se deslizaran unas sobre las otras en una imagen de movimiento que se ha ido formando a lo largo del tiempo.

Unfortunately, this plan was never completed. Interrupted by the Civil war, only one chalet module was built. Deeply disheartened, the architect fled with his family to France leaving behind an architectural gem. Sooner than later, the chalet was occupied by militias who quickly transformed its striking interior into a bunker used as a strategic point in the region. Today, empty and bearing the scars of war, the chalet is a 20th-century architectural heritage at stake, as it lies in a serious state of neglect, abandonment, and degradation.

Desafortunadamente, este plan nunca llegó a completarse. Interrumpida por la Guerra Civil, sólo se construyó un módulo. Profundamente desanimado, el arquitecto huyó con su familia a Francia dejando atrás esta joya arquitectónica. El chalé fue ocupado por milicianos que rápidamente transformaron su llamativo interior en un búnker utilizado como punto estratégico en la región. Hoy, vacío y con las cicatrices de la guerra, el chalé es un patrimonio arquitectónico del siglo XX en un grave estado de abandono, abandono y degradación.

So, what is the architectural value of this chalet? Why is it a remarkable example of architectural and technical experimentation? And why is it considered a heritage of Lebanese architectural modernity, with the utmost need to be safeguarded, protected, and restored?

¿Cuál es el valor arquitectónico de este chalet? ¿Por qué es un notable ejemplo de experimentación arquitectónica y técnica? ¿Y por qué se considera un patrimonio de la modernidad arquitectónica libanesa, con la máxima necesidad de ser salvaguardado, protegido y restaurado?

In a conversation with Patricia Hindié, daughter of the now-deceased architect and only remaining member of the family to follow-up on the legacy of her father, Patricia recalls her childhood memories inside this chalet and describes her experience of inhabiting it in what she says is similar to “inhabiting the oblique” due to the chalet’s unusual internal configuration.

En conversación con Patricia Hindié, hija del ya fallecido arquitecto y único miembro de la familia que queda para dar seguimiento al legado de su padre, Patricia rememora sus recuerdos de infancia dentro de este chalet y describe su experiencia de habitarlo en lo que ella dice es similar a “habitar el oblicuo” debido a la inusual configuración interna del chalet.

“The chalet really demonstrates my father’s remarkable inventiveness”, she stated. “Not because of its modularity, but because of the challenge of building on a slope. In the mountains, it is the slope, more than anything else, that determines the project’s architectural quality”.

“El chalet realmente demuestra la notable inventiva de mi padre”, afirmó. “No por su modularidad, sino por el desafío de estar construido sobre la pendiente. En la montaña, más que cualquier otra cosa, la que determina la calidad arquitectónica del proyecto”.

It is true that from the outside, the chalet is a purely hexagonal volume. However, from the inside, this oblique volume is an occupiable one – a space for living in. This pretty much recalls the work of French architect Claude Parent, distinguished in his radical and provocative explorations of the “Function of the Oblique”. What is quite interesting is that Parent and Hindié belonged to the same era. Founded on the sensation of bringing awareness to the body in motion, the “Function of the Oblique” dictated that buildings should feature slopes, be wall-free where possible, have a predominance of space over surface, hence encouraging the movement of people.

Es cierto que, desde el exterior, el chalet es un volumen puramente hexagonal. Sin embargo, el interior es un volumen oblicuo, un espacio para vivir. Esto recuerda bastante al trabajo del arquitecto francés Claude Parent, distinguido en sus exploraciones radicales y provocativas de la “Función del oblicuo”. Lo que es bastante interesante es que Parent e Hindié pertenecían a la misma época. Fundada en la sensación de llevar la conciencia al cuerpo en movimiento, la “Función del Oblicuo” dictaba que los edificios debían tener pendientes, estar libres de paredes en lo posible, tener un predominio del espacio sobre la superficie, favoreciendo así el movimiento de las personas.

These principles were implemented in Hindié’s mountain chalet. Designed to correspond to the traditional Lebanese habit of “owning a second home for the weekend”, the chalet was built to promote a life of close communication between the members of the family. Here, architecture becomes the underlying support for a livable flow of movement where the oblique isn’t merely a surface but a space with a broader range of uses. This architectural dynamic resulted by titling the axis enables individuals to be in a state of participation.

Estos principios se implementaron en el chalet de montaña de Hindié. Proyectado para corresponder al hábito tradicional libanés de “poseer una segunda casa para el fin de semana”, el chalet fue construido para promover una vida de estrecha comunicación entre los miembros de la familia. Aquí, la arquitectura se convierte en el soporte subyacente de un flujo de movimiento habitable donde el oblicuo no es solo una superficie sino un espacio con una gama más amplia de usos. Esta dinámica arquitectónica resultante de la titulación del eje permite que los individuos estén en un estado de participación.

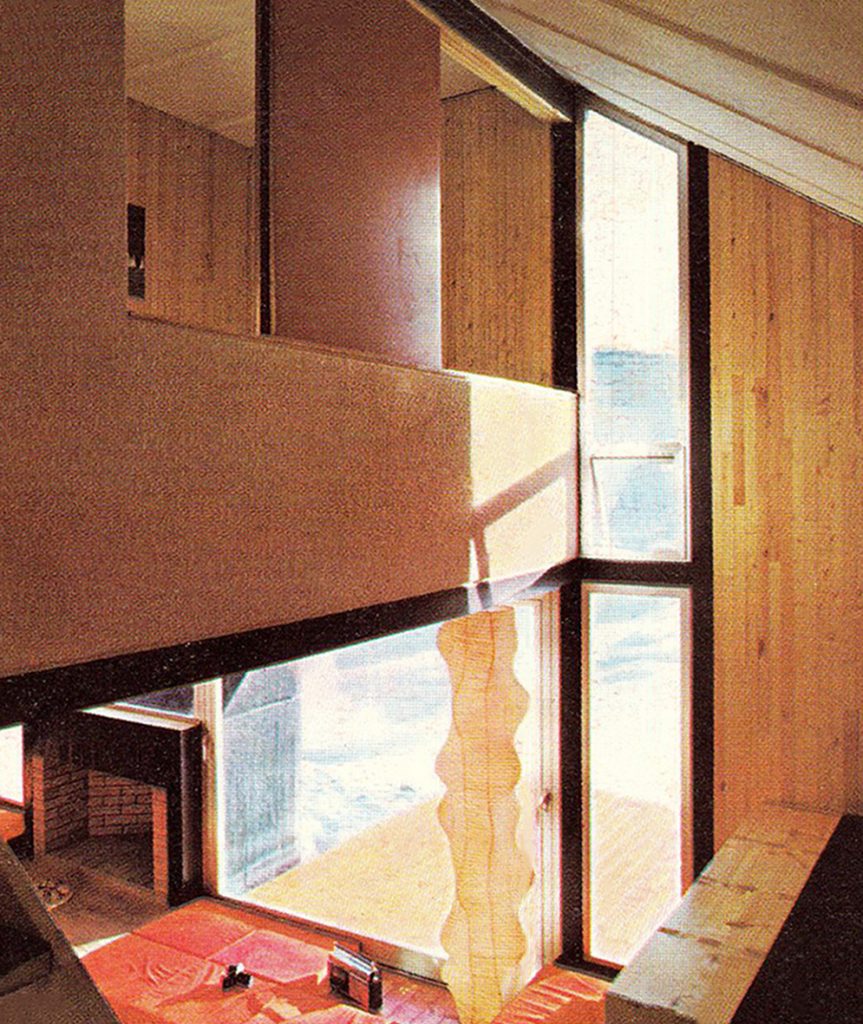

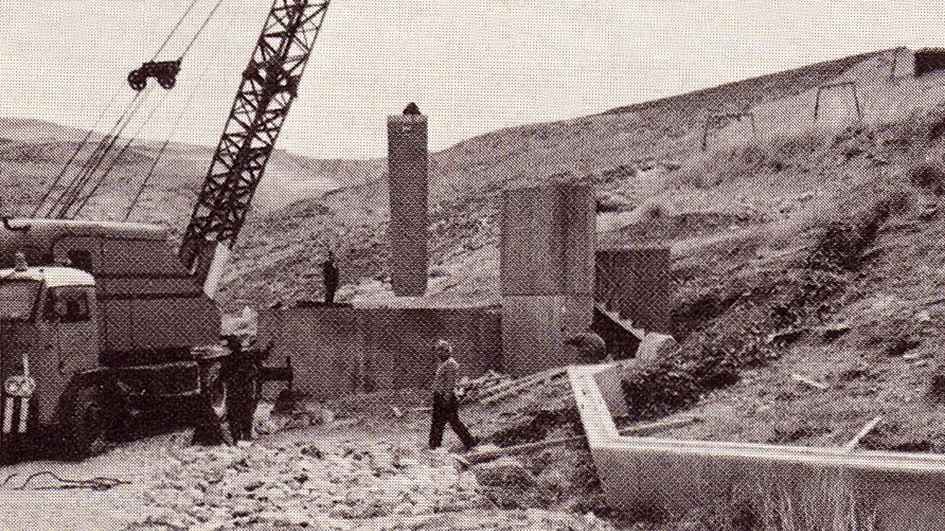

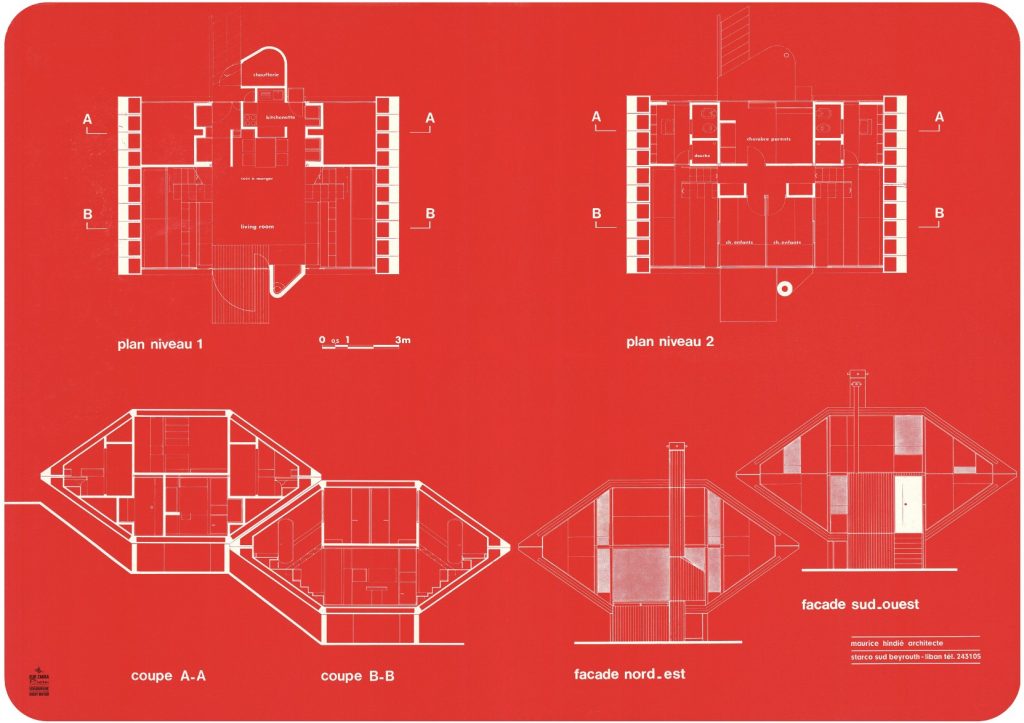

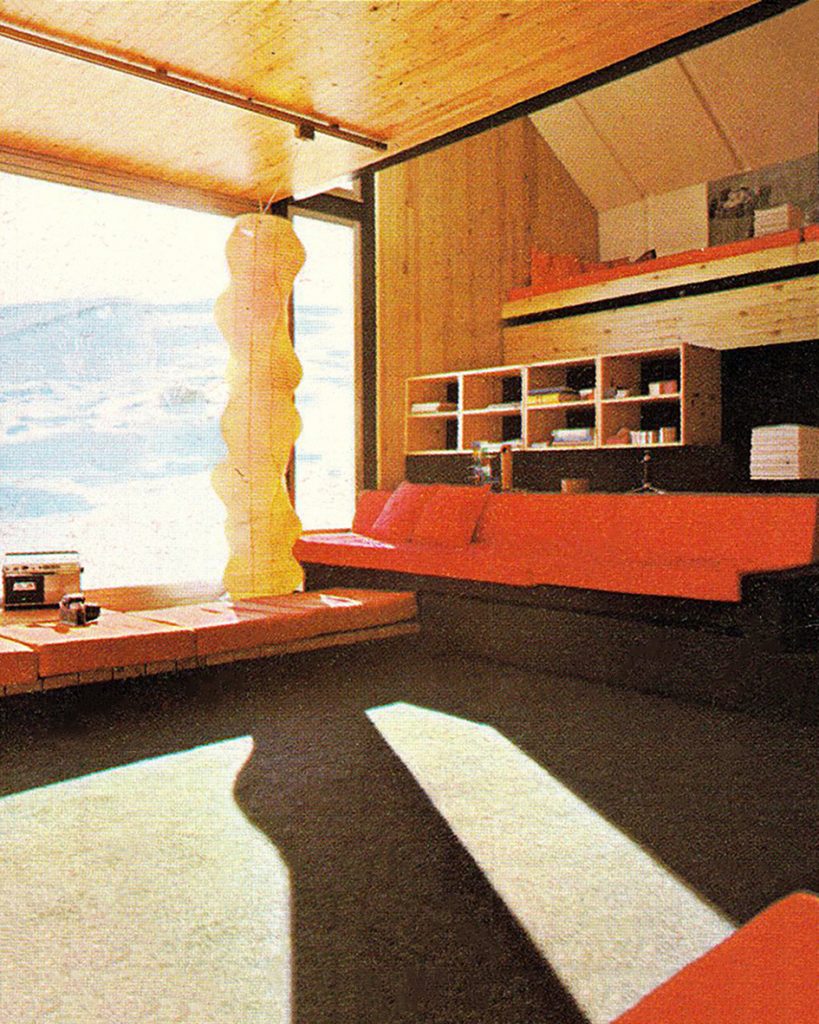

In the case of the chalet, a suspended floor, limited to the central area, allows communication between the ground floor and the first through a double-height formed on both sides. The living room, which also communicates with the dining room and kitchen, is made of steps, transversely placed and covered with carpet and cushions. Clearly, the architect did not opt for traditional furniture. To accentuate the idea of a home-refuge, the carpet (of uniform color) covering the floor and steps was brought onto the walls, hence making the cushions, doors, and radiators (treated with vivid colors) stand out. This warm interior, complemented by a fireplace built as a separate volume protruding from the facade, comes in contrast to the cold atmosphere outside.

En el caso del chalet, una planta suspendida, limitada a la zona central, permite la comunicación entre la planta baja y la primera a través de una doble altura formada a ambos lados. El salón, que también comunica con el comedor y la cocina, está formado por escalones, colocados transversalmente y revestidos con moqueta y cojines. Claramente, el arquitecto no optó por muebles tradicionales. Para acentuar la idea de hogar-refugio, la moqueta (de color uniforme) que recubría el suelo y los escalones se llevó a las paredes, destacando así los cojines, las puertas y los radiadores (tratados con colores vivos). Este cálido interior, complementado por una chimenea construida como un volumen separado que sobresale de la fachada, contrasta con el frío ambiente exterior.

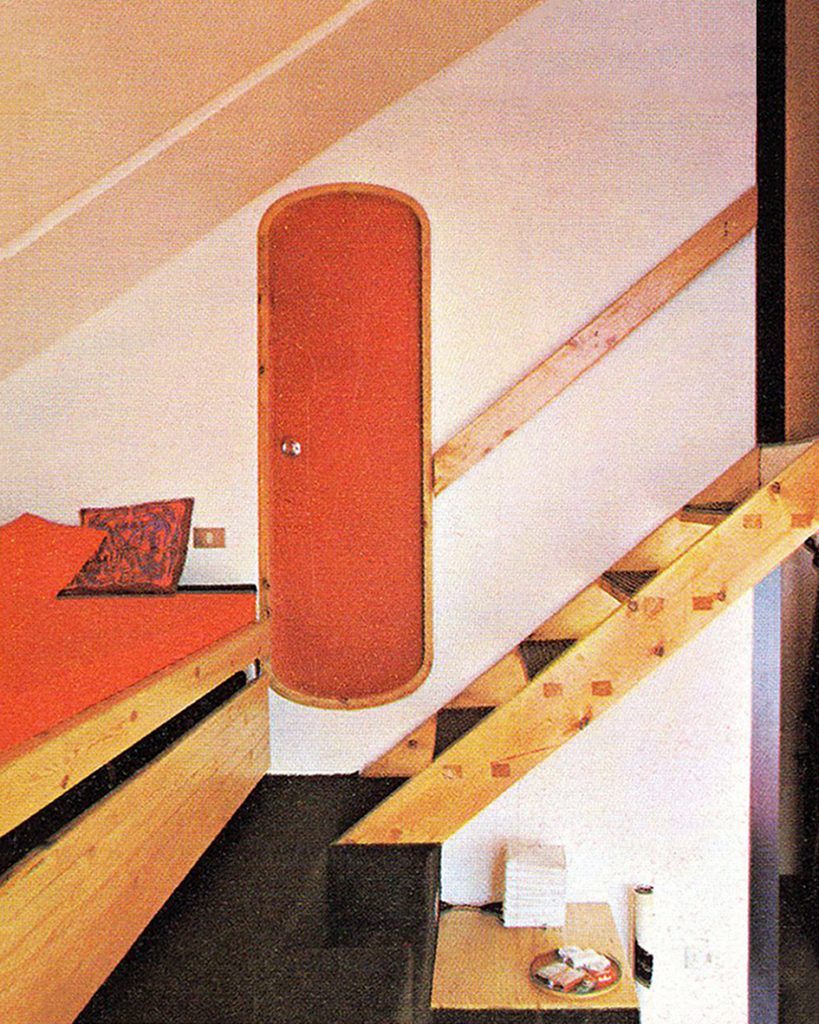

On the first floor are located the bedrooms (two children bedrooms and parent’s bedroom), widely overlooking the living room. The bathrooms, however, are located on an intermediate level, in the service area. The two levels are connected by ladders. According to Dr. George Arbid, founder and director of the Arab Center for Architecture (ACA) in Beirut where the chalet’s drawings are preserved, the rounded corners of the bathroom doors were not merely a design feature. They had a technical dimension. Hindié wanted to prevent the doors from touching the oblique incline tangentially; therefore, he rounded the corners to avoid contact.

En la primera planta se ubican los dormitorios (dos dormitorios de niños y dormitorio de padres), con amplias vistas al salón. Los baños, en cambio, se ubican en un nivel intermedio, en el área de servicio. Los dos niveles están conectados por escaleras. Según el Dr. George Arbid, fundador y director del Centro Árabe de Arquitectura (ACA) en Beirut, donde se conservan los dibujos del chalet, las esquinas redondeadas de las puertas del baño no eran simplemente una característica de diseño. Tenían una intención más técnica. Hindié quería evitar que las puertas tocaran tangencialmente la rampa oblicua; por lo tanto, redondeó las esquinas para evitar el contacto.

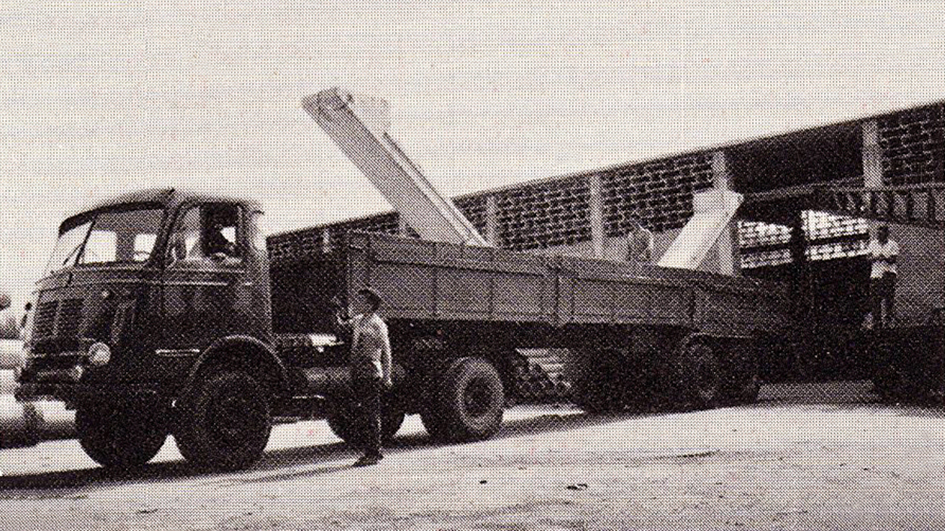

From an economic point of view and given the elevated cost of construction in the mountains (cost of bringing specialized workforce and cost of transporting material such as aggregates and cement from the city), the driving concept of the chalet was that of prefabrication. In a time where prefabrication in Lebanon was not common enough, Hindié considered it to be the construction method of the future. According to him, this adopted method of construction reduces on-site operations to the simple assembly of the parts themselves.

Desde un punto de vista económico, y dado el elevado coste de construcción en la montaña (coste de traer mano de obra especializada y coste de transporte de materiales como áridos y cemento desde la ciudad), se decidió utilizar elementos prefabricados. En una época en la que la prefabricación en el Líbano no era lo suficientemente común, Hindié puso los cimientos para desarrollar esta técnica en el país. Según él, este método de construcción adoptado reduce las operaciones in situ al simple montaje de las propias piezas.

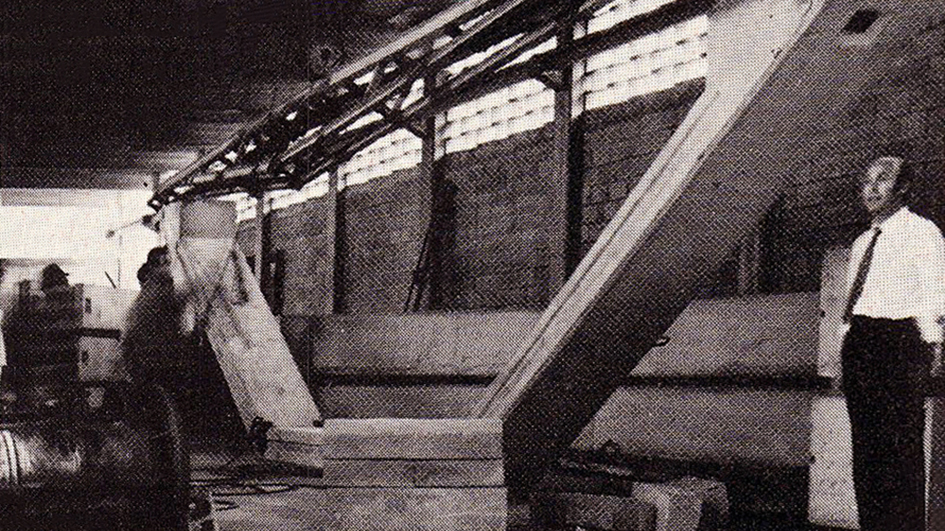

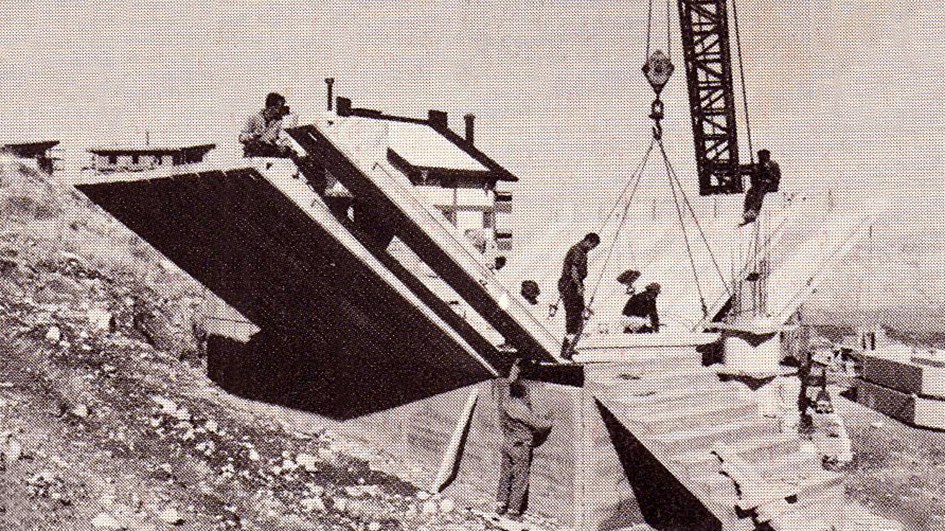

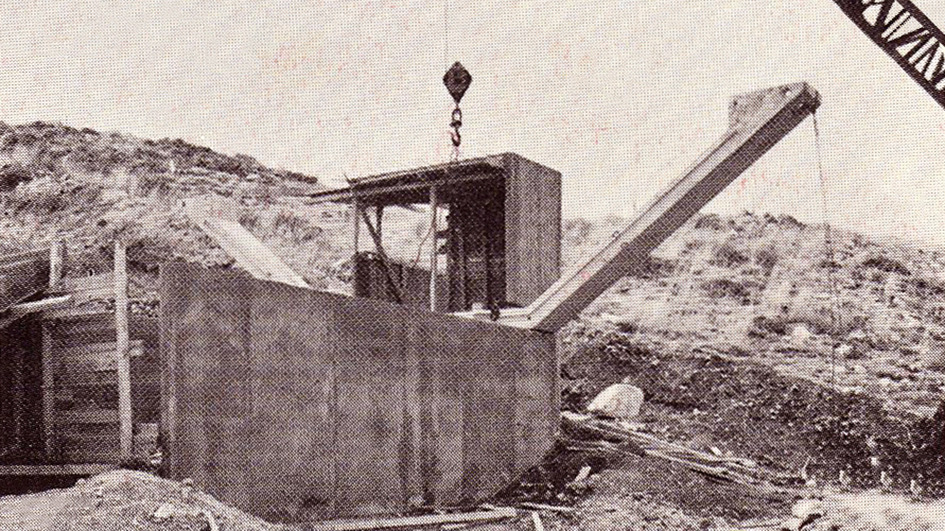

In terms of structure, the shell of the chalet consists of 10 inferior and 10 superior open U-shaped elements (11 m long, 70 cm wide, and 30 cm thick), precast in factory. Bound together at the edge of the hexagon with transverse tie rods and hyperstatic bindings, the U-shaped concrete elements form the base and the roof. In addition, to reduce their weight, the elements are hollowed out in their thickness by means of a lost formwork made of expanded polystyrene.

Estructuralmente, la envolvente del chalé está formada por 10 elementos inferiores abiertos y 10 superiores en forma de U (11 m de largo, 70 cm de ancho y 30 cm de espesor), prefabricados en fábrica. Unidos en el borde del hexágono con tirantes transversales y uniones hiperestáticas, los elementos de hormigón en forma de U forman la base y el techo. Además, para aligerar su peso, los elementos se van vaciando en su espesor mediante un encofrado perdido de poliestireno expandido.

It is important to note that Hindié paid particular attention to openings to the landscape. The facades of the chalet consisted of large windows with mounted aluminum frames; whereas the non-glazed parts were made of sandwiched panels of double eternit sheets filled with polyurethane foam to ensure thermal insulation.

Es importante señalar que Hindié prestó especial atención a las aperturas al paisaje. Las fachadas del chalet constaban de grandes ventanales con marcos de aluminio montados; mientras que las partes no vidriadas se realizaron con paneles sándwich de doble lámina de eternit rellenos de espuma de poliuretano para asegurar el aislamiento térmico.

The construction was completely prefabricated, and the chalet prototype was realized in just 60 days.

La construcción fue completamente prefabricada y el prototipo de chalet se realizó en solo 60 días.

Sources:

- Ms. Patricia Hindié, daughter of the architect.

- Dr. George Arbid, founder and director of the “Arab Center for Architecture” in Beirut.

- “Les Chalets de Faraya”, article in Arabic and in French published in “Al-Mouhandess” magazine, p. 32-35.

- “Châlet Hindié”, article in Italian published in “Ville Giardini: Ville Prefabbricate e Industrializzate”, Görlich Editore Milano, October 1972.

- “Refuge dans les monts du Liban”, article in French published in “L’œil” magazine, March 1974, p. 60-61.

- Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou.

Author’s Bio:

Gioia Sawaya is an architect and researcher from Lebanon. She holds a B.Arch from NDU, Lebanon and a Masters in “Strategic Design of Spaces” from IE, Spain. Gioia’s research methodology focuses on the role of theory in relation to the design process, examining the possibilities that challenge the rethinking of architecture in a novel way. Currently, her research interests look into the intersections between design and sociology, going beyond the traditional boundaries into the shifts that are transforming the way people live today.

Cover Photo: “Ville Giardini: Ville Prefabbricate e Industrializzate”, Görlich Editore Milano, October 1972.