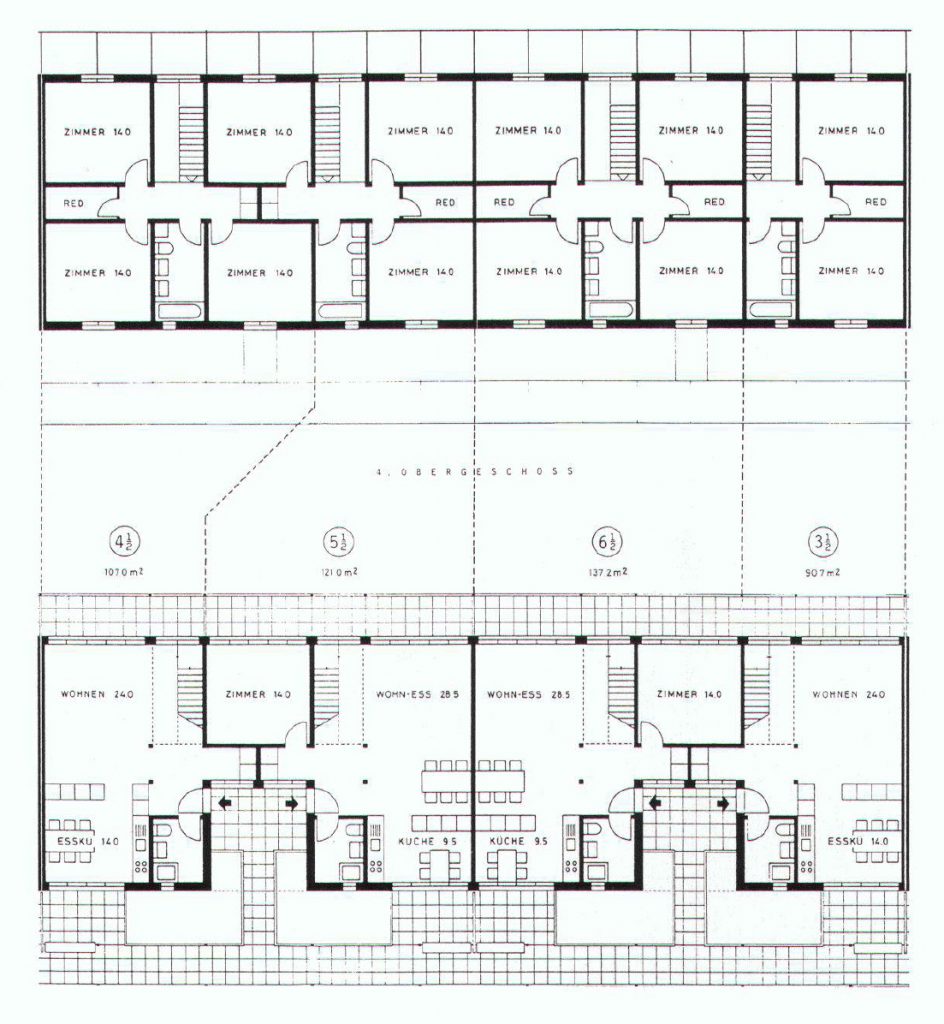

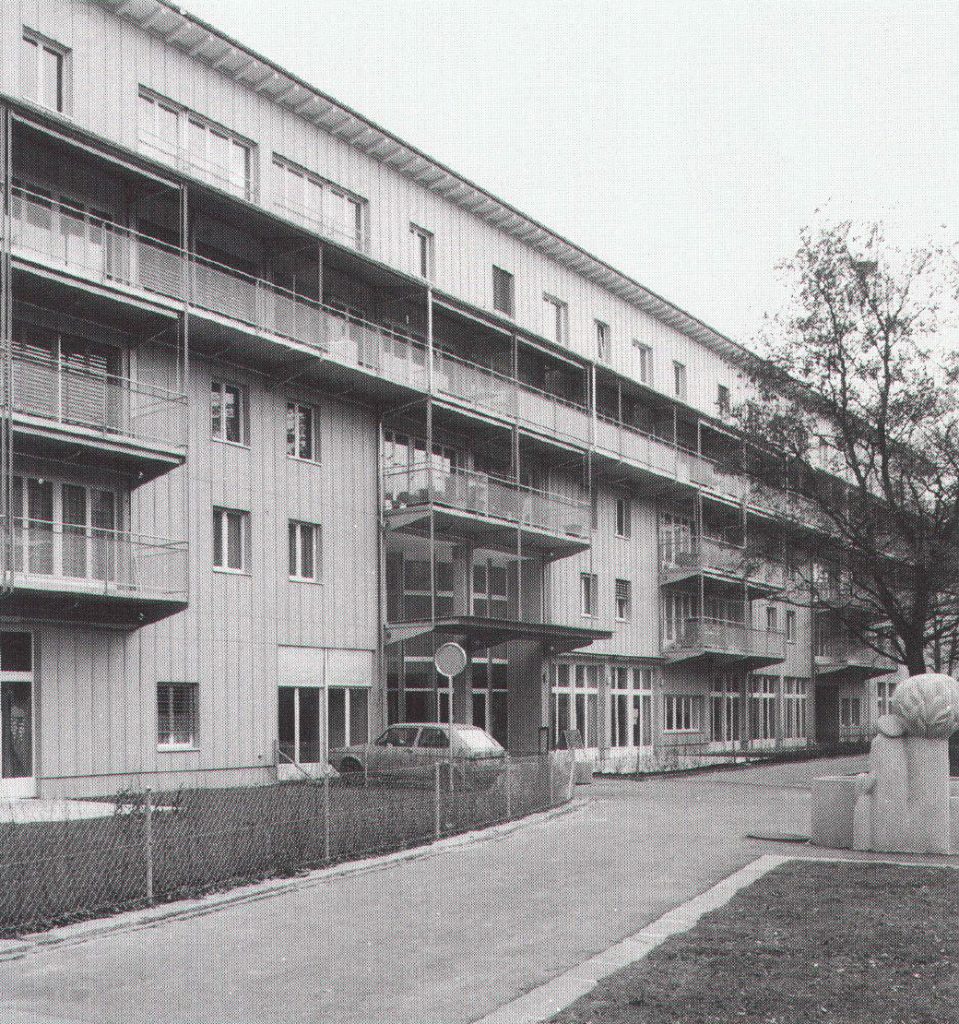

The developer, the Protestant Women’s Association, wanted to offer flats for those residents who – for economic or social reasons – were excluded from the housing market. In addition to the subsidy requirements of the federal government, the city and the canton (construction costs below CHF 500), the programme demanded sophisticated flat types (with changeable living forms and flat distributions) and a diverse range of services (café, school, crèche, maternity centre, offices, studios, available rooms). Beyond the individual case, this programme has general significance – at least for urban outer quarters (which would have justified a public competition instead of a competition by invitation).

El promotor, la Asociación de Mujeres Protestantes, quería ofrecer pisos a los residentes que, por razones económicas o sociales, estaban excluidos del mercado de la vivienda. Además de los requisitos de subvención del gobierno federal, la ciudad y el cantón (costes de construcción inferiores a 500 CHF), el programa exigía tipos de pisos sofisticados (con formas de vida y distribuciones de pisos cambiantes) y una gama de servicios diversa (cafetería, escuela, guardería, centro de maternidad, oficinas, estudios, habitaciones disponibles). Más allá del caso individual, este programa tiene un significado general, al menos para los barrios periféricos urbanos (lo que habría justificado un concurso público en lugar de un concurso por invitación).

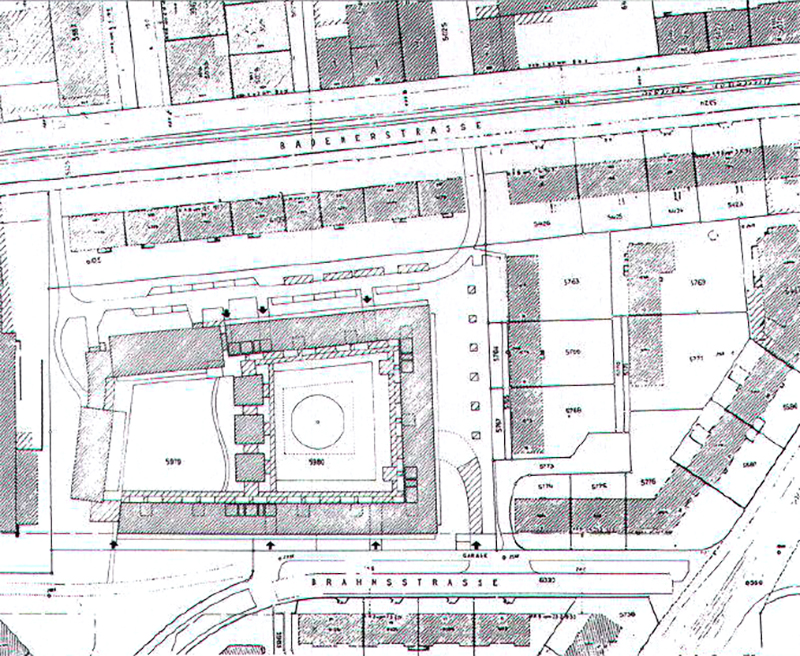

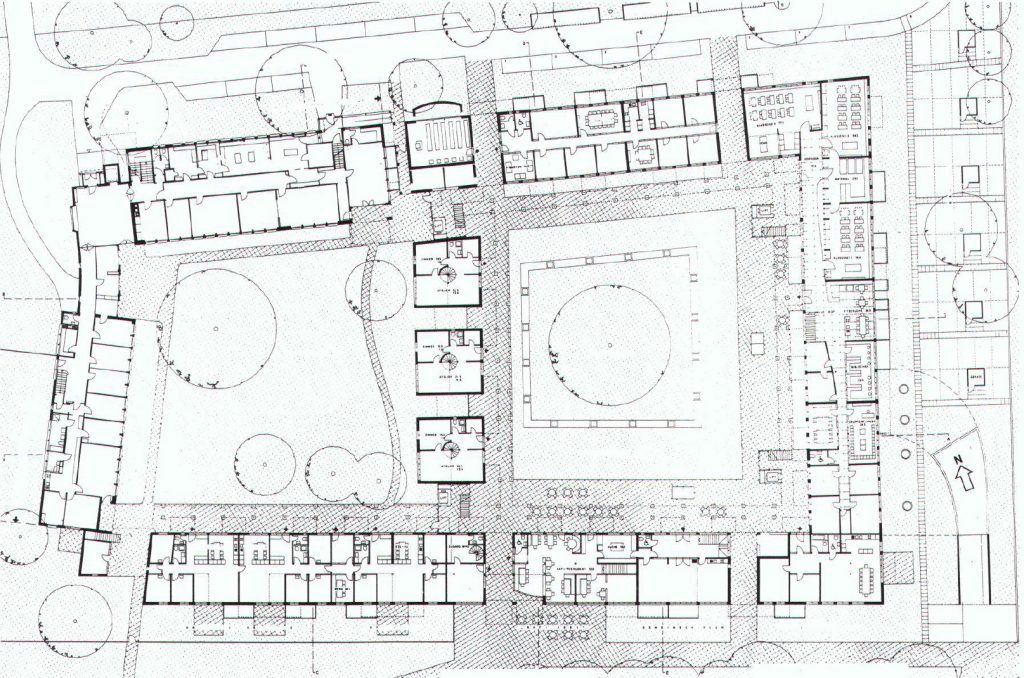

The executed project offers design learning material by illustrating its own and immanent problems of traditional courtyard perimeter developments. The old residential courtyards – such as the Erismannhofin Zurich or the Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin – are characterised by architectural ambivalence: they are neither private nor public. Often they lie fallow, are subject to prohibitions, sometimes they are en vogue and overcrowded. The love of courtyards seems to follow a zeitgeist cycle that makes the specific relationship between anonymity and privacy unpredictable. This experience would correspond to a courtyard architecture that remains undefined in order to keep the scope of uses and forms of appropriation open.

El proyecto ejecutado ofrece material de aprendizaje de diseño al ilustrar los problemas propios e inmanentes de los desarrollos perimetrales de los patios tradicionales. Los antiguos patios residenciales -como el Erismannhof de Zúrich o el Hufeisensiedlung de Berlín- se caracterizan por su ambivalencia arquitectónica: no son ni privados ni públicos. A menudo están en barbecho, son objeto de prohibiciones, a veces están de moda y están abarrotados. La afición a los patios parece seguir un ciclo zeitgeist que hace imprevisible la relación concreta entre anonimato y privacidad. Esta experiencia se correspondería con una arquitectura de patios que permanece indefinida para mantener abierto el ámbito de los usos y las formas de apropiación.

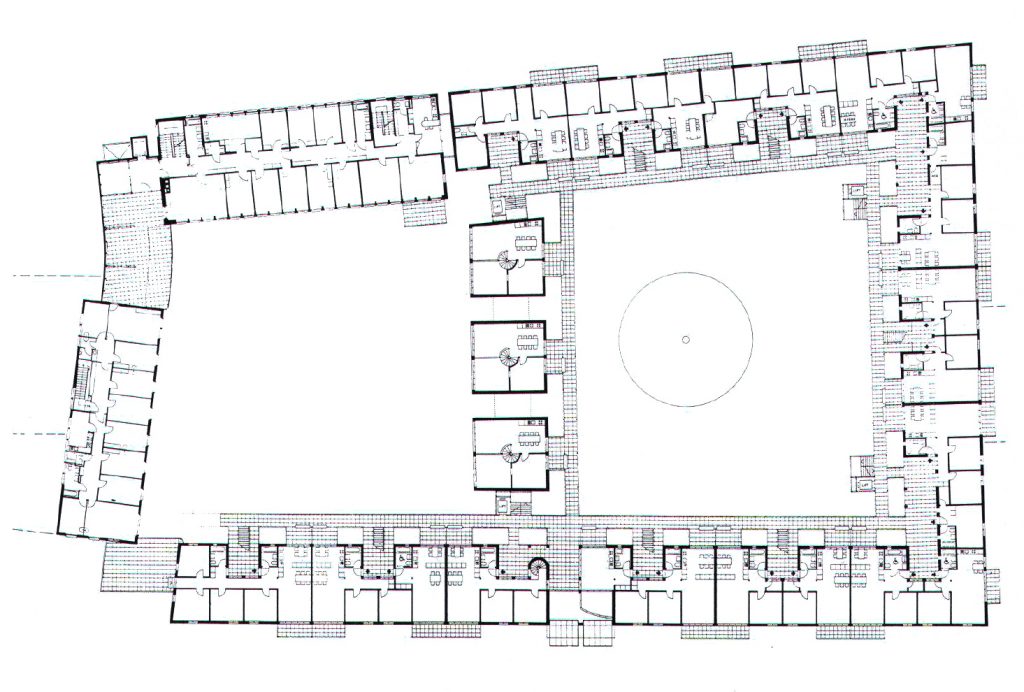

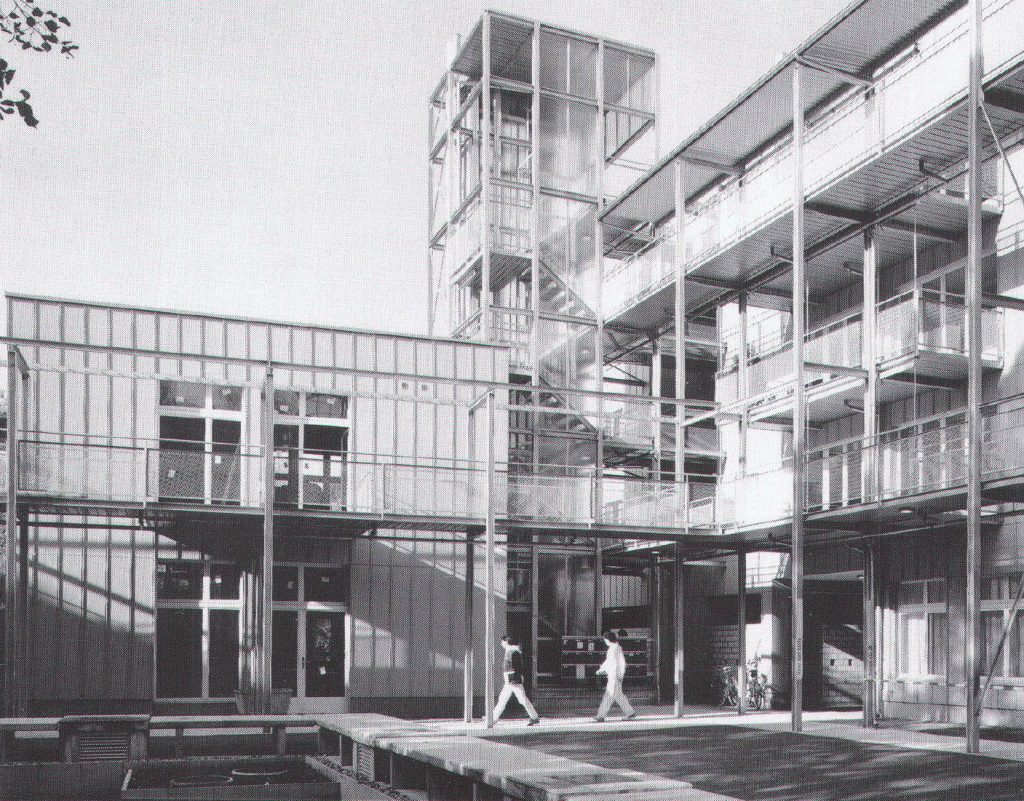

The Brahmshof differs from the traditional residential courtyard in that it has perimeter arcades that are inserted between the building and the courtyard as an independent structure. Their plasticity cushions the usually “hard”, transitionless boundary of the courtyard. Although a “curtain” falls in front of the flats, one feels exposed to the (real or imagined) gaze of surveillance in the courtyard. This impression is not created solely by the largely closed form of a traditional courtyard perimeter development: the courtyard is too small to appear ambivalent or public and too large to signal privacy. An open ground floor area of the studio houses (the courtyard fixtures) could have contributed to an “urbanisation” of this courtyard (the two courtyards would have been spatially better connected by this than by a reduced building height of the courtyard fixtures). The Brahmshof also points to the difficulties of a contextual urban design that is true to tradition. It leaves current questions about the relationship between anonymity and privacy unanswered.

El Brahmshof se diferencia del patio residencial tradicional en que tiene arcadas perimetrales que se insertan entre el edificio y el patio como una estructura independiente. Su plasticidad amortigua el límite habitualmente “duro” y sin transición del patio. Aunque una “cortina” cae delante de los pisos, uno se siente expuesto a la mirada (real o imaginaria) de la vigilancia en el patio. Esta impresión no se debe únicamente a la forma en gran medida cerrada de una urbanización con patio tradicional: el patio es demasiado pequeño para parecer ambivalente o público y demasiado grande para señalar la privacidad. Una zona abierta en la planta baja de las casas-estudio (los accesorios del patio) podría haber contribuido a una “urbanización” de este patio (los dos patios habrían estado espacialmente mejor conectados por esto que por una altura de construcción reducida de los accesorios del patio). El Brahmshof también señala las dificultades de un diseño urbano contextual que sea fiel a la tradición. Deja sin respuesta las preguntas actuales sobre la relación entre anonimato y privacidad.

Text by Red, from Werk, Bauen + Wohnen, 72, 1992

VIA:

Werk, Bauen + Wohnen, 72, 1992