The Bagh-e Babur garden is the final resting place of the first Mughal Emperor, Babur. Although present-day Afghanistan was not Babur’s original homeland (he was born in Ferghana in present-day Uzbekistan), he felt sufficiently enamored of Kabul that he desired to be buried here. When Babur died in 1530 he was initially buried in Agra against his wishes. Between 1539 and 1544 Sher Shah Suri, a rival of Babur’s son Humayun, fulfilled his wishes and interred him at Babur’s Garden. The headstone placed on his grave read “If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this.”

El jardín Bagh-e Babur es el lugar de descanso final del primer emperador mogol, Babur. Aunque el Afganistán actual no era la patria original de Babur (nació en Ferghana en el actual Uzbekistán), se sintió lo suficientemente enamorado de Kabul como para desear ser enterrado allí. Cuando Babur murió en 1530, inicialmente fue enterrado en Agra, en contra de sus deseos. Entre 1539 y 1544, Sher Shah Suri, rival del hijo de Babur, Humayun, decidió cumplir sus deseos y enterrarlo en el Jardín de Babur. En la lápida colocada sobre su tumba está escrito lo siguiente: “Si hay un paraíso en la tierra, es esto, es esto, es esto”.

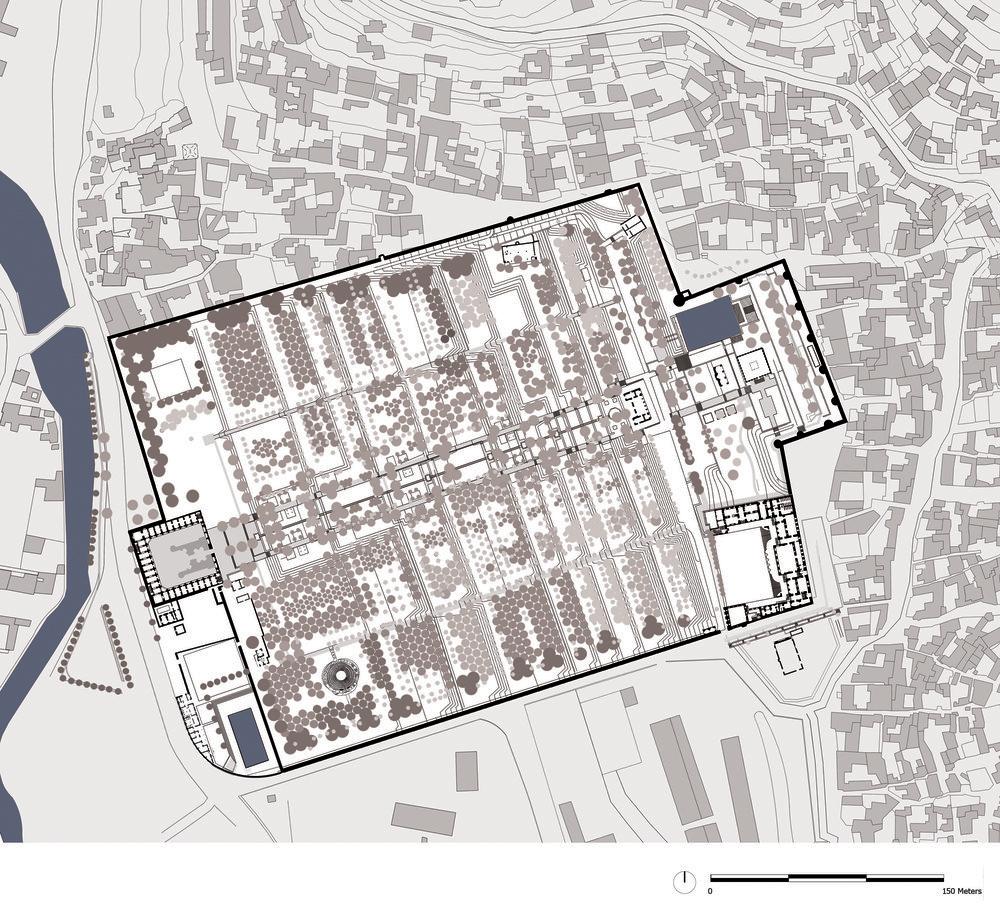

of terraces, the perimeter walling and the settlement adjacent to the site are also visible.

Image via Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

The garden was laid out as a series of 15 stepped terraces on a hillside in southwest Kabul. Its axis points toward Mecca. Babur’s grave is located on the fourteenth terrace and was originally surrounded by a screen of white marble. Although the screen was destroyed by warfare and vandalism in the 20th century, it was rebuilt between 2002-06 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture follownig a drawing by Charles Masson in the 19th century. Southwest of the grave, on the next lower terrace, Shah Jahan built a small mosque in 1645-46. He also rebuilt the water channels that flow through the central axis of the garden, and added a caravanserai marketplace at the base of the garden. On the fifteenth level he buried Babur’s grand-daughter, Ruqaiya Sultan Begum (d. 1626), in a tomb with a marble jali screen.

El jardín fue organizado en una serie de 15 terrazas escalonadas sobre una ladera en el suroeste de Kabul. Su eje apunta hacia La Meca. La tumba de Babur se encuentra en la decimocuarta terraza que originalmente estaba rodeada por un entramado de mármol blanco. Aunque dicho entramado fue destruido durante las guerras y el vandalismo en el siglo XX, fue reconstruida entre 2002 y 2006 por el Aga Khan Trust for Culture siguiendo un dibujo de Charles Masson del siglo XIX. Al suroeste de la tumba, en la siguiente terraza inferior, Shah Jahan construyó una pequeña mezquita en 1645-46. También reconstruyó los canales de agua que fluyen a través del eje central del jardín, y agregó un mercado caravanserai en la base del jardín. En el decimoquinto nivel, enterró a la nieta de Babur, Ruqaiya Sultan Begum (m. 1626), en una tumba con otro entramado de mármol de jali.

The 19th century saw major alterations to the garden. Beginning in 1842, an earthquake damaged the garden walls and Shah Jehan’s mosque. In the 1880s, the local ruler Amir Abdurahman Khan refurbished the gardens in a style that influenced more by European tastes than Mughal precident. He added a central pavilion and a large residence, know called the Queen’s Palace, for his wife Bibi Halima. The garden was converted into a public park during the rule of Nadir Shah in the 1930s with the construction of pools, reservoirs, and flower gardens down the central axis of the landscape. Finally, a modern swimming pool and greenhouse were constructed in the 1980s.

Durante el siglo XIX, el jardín sufrió graves alteraciones. En 1842, un terremoto dañó las paredes del jardín y la mezquita de Shah Jehan. En la década de 1880, el gobernante local Amir Abdurahman Khan renovó los jardines en un estilo que estuvo influenciado en una estética europea obviando el precinto de Mughal: agregó un pabellón central y una gran residencia, conocida como el Palacio de la Reina, para su esposa Bibi Halima. El jardín se convirtió en un parque público durante el gobierno de Nadir Shah en la década de 1930 y se construyeron piscinas, embalses y jardines de flores en el eje central del paisaje. Finalmente, en la década de 1980 se construyó una moderna piscina y un invernadero.

Warfare between competing factions in Kabul posed a serious threat beginning in 1992. Fighting in the area caused a fire that destroyed the Queen’s Palace, and the mosque was seriously damaged. Irrigation pumps were stolen and the remaining trees were chopped down for firewood. Worse still, mines and unexploded munitions turned the garden into a dangerous no-man’s land.

La guerra entre distintos grupos armados dentro de Kabul planteó una severa amenaza a partir de 1992 para el propio jardín. Los combates en la zona provocaron un incendio que destruyó el Palacio de la Reina, y la mezquita sufrió graves daños. Las bombas de riego fueron robadas y los árboles restantes fueron cortados para obtener leña. Aún peor, las minas y las municiones sin explotar convirtieron el jardín en una peligrosa tierra de nadie.

At present, in 2011, the garden has been completely restored due to the efforts of the UNCHS Habitat and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. After clearing mines and performing a comprehenisive archaeological survey, the AKDN replanted the garden and restored most of the original buildings. It now serves both as a tourist attraction in this war-scarred city and as a place of recreation for the city’s residents.

En la actualidad, el jardín ha sido totalmente renovado gracias a los trabajos que se realizaron en 2011 y que fueron apoyados por UNCHS Habitat y Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Después de desminar la zona y realizar un estudio arqueológico integral del recitó, el AKDN replantó el jardín y restauró la mayoría de los edificios originales. Ahora sirve tanto como atracción turística en esta ciudad devastada por la guerra como lugar de recreación para los residentes de la ciudad.

Text via Asian Historical Architecture.

Images via Asian Historical Architecture and Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

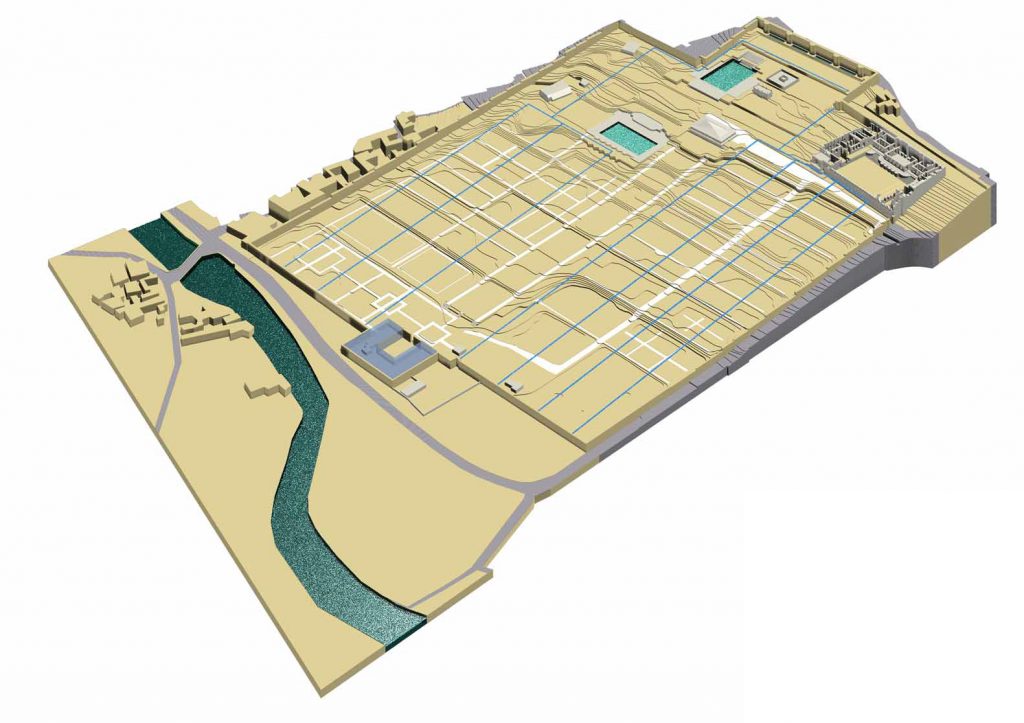

This projection shows a birds-eye view of the current state of the garden looking to the north-east, showing the river in the foreground. Indicated on the model are the principal contours, the network (in grey and white) of roads, paths and stairs and (in blue) the layout of irrigation channels and reservoirs including the lower swimming pool that it is proposed to remove. The caravanserai area (in grey), to be redeveloped during 2004, lies at the centre of the western perimeter, at the base of the garden. The ruins of the Queen’s Palace lie in the south-eastern corner

Image via Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Image via Asian Historical Architecture